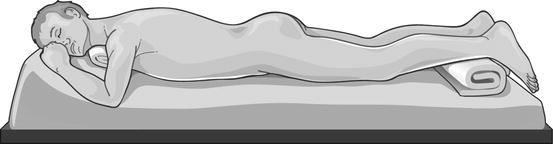

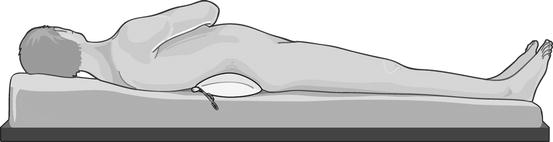

Fig. 10.1

Prone decubitus – frontal view (© Carole Fumat)

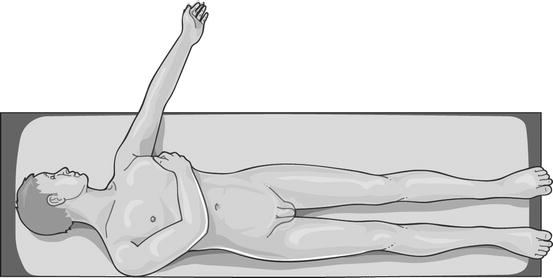

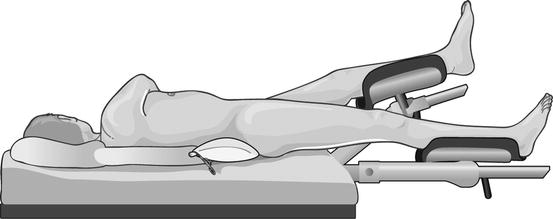

Fig. 10.2

Prone decubitus – lateral view (© Carole Fumat)

Table 10.1

Advantages and disadvantages of the prone position

Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Wide surgical field for renal puncture | Patient discomfort |

Easier upper calyceal puncture | Difficult retrograde access if needed |

Enough room for nephroscopic manipulation | Need of several nurses for intraoperative change of the decubitus from lithotomic to prone |

Feasibility of bilateral procedures | Increased radiological hazard to the urologist’s hands operating within the fluoroscopic field |

Lower risk of lung, liver, and spleen injury with an upper pole puncture | Anesthesiological difficulties (especially in obese, kyphotic, and debilitated patients) |

Good distension of the collecting system | A more evident risk of iatrogenic injuries (mainly peripheral nerve damage and compartment syndrome) |

Table 10.2

Anaesthesiological problems in the prone position

Cardiovascular problems | Respiratory difficulties | Peripheral nervous system injuries | Pressure damages | Ischemic accidents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Reduced left ventricular compliance | Reduced lung compliance | Upper limbs (ulnar, radial, etc.) | Lip necrosis | Partial or total visual loss |

Decreased cardiac output | Risk of endotracheal tube kinking | Lower limbs (peroneal, sciatic, saphenous, etc.) | Breast necrosis | Hemiparesis |

Reduced venous return and venous stasis | Reduced thorax expansion for ribs compression by the body weight | Compartment syndromes | Liver necrosis | Quadriplegia |

Increased risk of thromboembolic complications | Rhabdomyolysis | Aphasia | ||

Poor access in case of unforeseen cardiovascular complications | ||||

Increased heart rate and total peripheral vascular resistance |

10.3 Modifications of the Prone Position for PNL

Several modifications of the prone position have been proposed during the years, mainly in order to gain the possibility of a working retrograde access to the renal cavities, and only recently to obviate the recognized anesthesiological problems. This trend is going on in the recent surgical practice and literature, with urologists from all over the world reporting their experience with alternative positions for PNL:

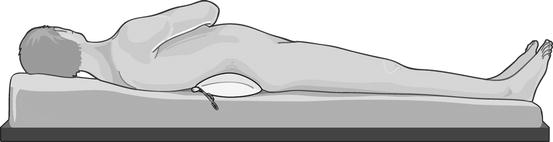

10.4 The Supine and the Modified Supine Positions for PNL

As already mentioned in previous chapters, the supine position – conceived in the late 1980s and pioneered by Gabriel Valdivia Urìa – only recently started to gain acceptance and diffusion among urologists (Figs. 10.3 and 10.4).

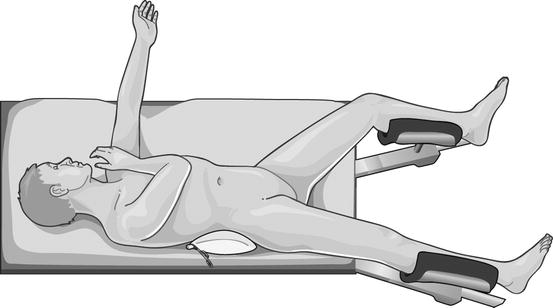

Fig. 10.3

Supine decubitus (Valdivia position) – frontal view (© Carole Fumat)

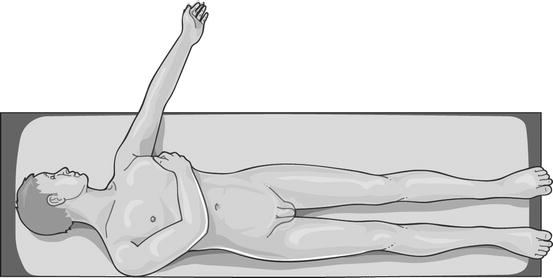

Fig. 10.4

Supine decubitus (Valdivia position) – lateral view (© Carole Fumat)

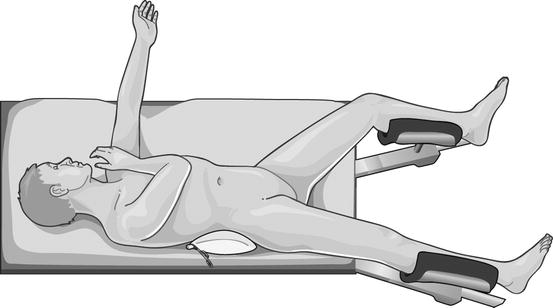

In particular, we appreciated from the very beginning the modification of the supine Valdivia position proposed by Gaspar Ibarluzea, called the Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia (GMSV) position (Figs. 10.5 and 10.6), which we found extremely innovative, versatile, and handy. This position (see Chap. 11) combines the supine decubitus with a modified lithotomy position of the legs, presents few disadvantages, and optimally supports a versatile combined approach to the upper urinary tract, being safe, effective, ergonomic, and extremely appreciated by anesthesiologists as well (Table 10.3) [32–38].

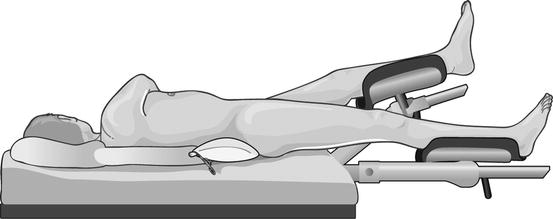

Fig. 10.5

Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia decubitus – frontal view (© Carole Fumat)

Fig. 10.6

Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia decubitus – lateral view (© Carole Fumat)

Table 10.3

Advantages and disadvantages of the supine and supine-derived positions

Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Easy and comfortable patient positioning | The upper pole of the kidney is deeply located within the rib cage = More challenging superior calyceal puncture (less important because such calyces are routinely entered retrogradely by ureteroscopy, avoiding hepatosplenic and pleuric risk of injury) |

No need of repositioning the anaesthetized patient (less need of trained personnel, less occupational load due to shifting of heavy loads, a single sterile draping) | Decreased filling of the collecting system = More difficult nephroscopy (additional retrograde irrigation can be provided, but low intrarenal pressures imply less risk of pyelovenous back flow and septic risk) |

The surgeon works sitting and with the hands outside the fluoroscopic field | More mobile kidney = More difficult puncture (constant counterpressure on the abdomen has been suggested during the access) |

Combined retrograde approach (with all implications) | Longer tract length = Need of extralong equipment in obese patients, decreased nephroscope mobility, more torque on renal parenchyma meaning more bleeding risk |

Optimal cardiovascular and airways control | Air bubbles produced during lithotripsy accumulate in the collecting system = Reduced quality of vision |

Less risk of colon injury | |

Less overall X-ray exposure (for the retrograde endoscopic contribution) | |

Better descending drainage and retrieval of stone fragments (the tract is horizontal or slightly inclined downwards) |

10.5 ECIRS (Endoscopic Combined IntraRenal Surgery)

ECIRS would not exist without the GMSV position [5, 28]. In fact, this position specifically and optimally supports this versatile antero-retrograde approach to the upper urinary tract.

ECIRS is a synergic approach in all its aspects, starting from the fact that it is a combination of retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) and PNL and going on with the intraoperative interaction among all operators (urologists, anaesthesiologists, nurses, scrub nurse, radiology technician, with the respective armamentaria); between retrograde and antegrade access; between rigid and flexible instruments; between endoscopes and accessories; among fluoroscopy, ultrasound, and Endovision technique for renal puncture; and between ECIRS itself and other surgical techniques like open surgery; laparoscopy, for instance, in case of associated ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) stricture; and Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL), in very selected and particular cases.

Although versatile in itself and rather complex at a first glance, ECIRS has been from the very beginning [5, 28] a completely standardized procedure, with the final aim to critically afford each step and maximize its safety, efficacy, and repeatability. The freedom of the urologist performing ECIRS lies in the fact that he/she is not the uncritical executor of a crystallized sequence of established steps, but rather an active figure continuously exerting his/her critical mind and choosing the best strategy for an optimal outcome, constantly related to the anatomical and clinical condition of the patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree