Fig. 48.1

Example of retroflexion view of anal brim. (a) Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN) 0-IIa grade 2 with immunohistochemical stain for p16 positive favoring an HPV-related pathogenesis. (b) AIN lesion on withdrawal of the endoscope

Advanced mucosal neoplasia usually refers to lesions with advanced histology (tubulovillous, villous or high grade dysplasia) and are generally ≥10 mm [2]. Large flat lesions or laterally spreading tumors can increase in size and extend over several mucosal folds before becoming invasive. However, smaller lesions can be invasive and the experienced endoscopist takes into account tactile as well as visual features before entertaining endoscopic removal. Mucosal lesion morphology is defined according to the Paris classification of neoplastic lesions [3, 4]. Type 0 lesions are superficial mucosal neoplasia classified as protruding, flat elevated or flat in general terms. Protruding lesions include pedunculated (0-Ip), subpedunculated (0-Isp) or sessile (0-Is). Flat elevated lesions have shoulders less than 2.5 mm and may be flat elevation of the mucosa (0-IIa) or a mixture of flat elevated and central depression (0-IIa + IIc) or flat elevated and raised broad based nodule (0-IIa + Is). Other formations include entirely flat lesions (0-IIb), depressed lesions (0-IIc) and excavated lesions (0-III). Type 1 lesions are polypoid carcinomas usually attached on a wide base. Type 2 lesions are ulcerated carcinomas and raised sharp margins. Type 3 lesions are ulcerated and have no definite limits. Type 4 lesions are non-ulcerated and diffusely infiltrating.

The surface topography of the mucosal lesion is best characterized as granular (G, nodular) nongranular (NG, flat) or mixed. Morphology can be enhanced with dye spraying of indigo carmine 0.4 % or crystal violet 0.05 % solutions, which helps demarcate margins and mucosal patterns. Mucosal morphology is extremely important because it predicts submucosal invasion in advanced lesions. A uniformly 0-IIa G lesion has a very low risk of submucosal invasion (~1 %) compared to the highest risk 0-IIa + c NG lesions with submucosal invasion of 67 % (relative risk, 54; P < 0.001) [5]. Depressed areas in neoplastic lesions are clearly associated with an increased risk of submucosal invasion [6, 7]. Other features of colorectal lesions include loss of lobulation within a large protruding nodule, fold convergence, demarcated depressed areas, stalk swelling and fullness should raise a suspicion of submucosal invasion [8].

Mucosal pit pattern (PP) are best described according to the Kudo system [9]. Mucosal PP are highlighted with high definition endoscopes and dye spray chromoendoscopy. Advanced imaging processing with light filters (narrow band imaging, Olympus Medical) or computer modulation of the image (intelligent color enhancement, Fujinon and i-scan, Pentax) can facilitate PP recognition without the dye spray using a virtual chromoendoscopy image. Type IV PP is the most common pattern and corresponds to a tubulovillous adenoma histology. Type III PP is seen with NG lesions and corresponds to tubular adenoma histology. Irregular PP are associated with intramucosal carcinoma or an invasive neoplasm. The Sano mucosal vascular patterns seen with narrow band imaging can further characterize advanced mucosal neoplasia using the capillary arrangements (regular brown mesh networks vs. irregular or complex branching and blind ending) to differentiate noninvasive and invasive lesions [10]. The relationship of PP with submucosal invasion appears to be more significant in sessile and superficial lesions more so than pedunculated lesions [8]. The use of PP recognition and micro vascular features are helpful in determining if a lesion is high risk for invasive disease but no features are uniformly reliable and there is considerable intraobserver variability with inexperienced operators. Therefore, proper tissue handling and histologic evaluation of resected lesions is imperative to guide subsequent care.

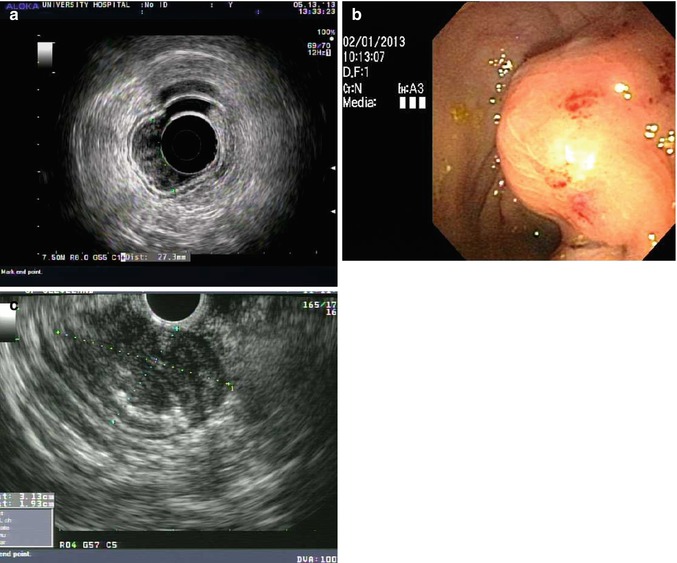

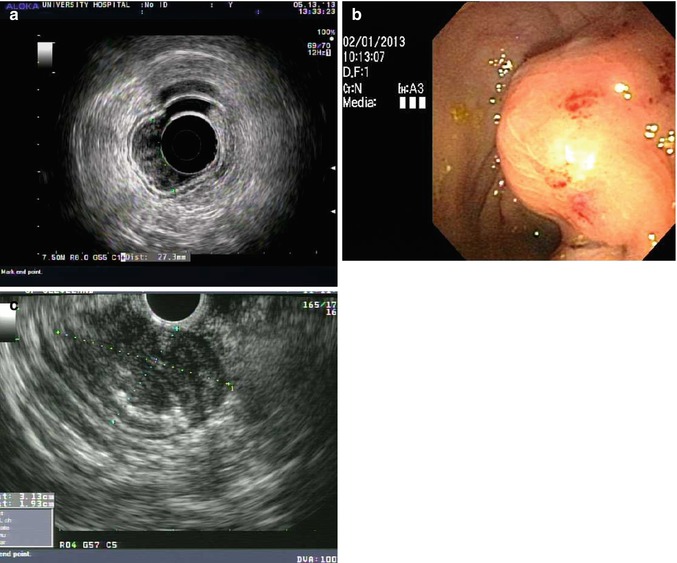

48.3 Endoscopic Ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is helpful to assess the depth of invasion for mucosal lesions and confirm the presence, size and location of subepithelial lesions. Fine needle aspiration and core biopsy of lesions and lymph nodes are possible with EUS guidance. EUS is not necessary before endoscopic removal of lesions with favorable morphologic features discussed above but can be helpful in large, depressed or ulcerated lesions. Figure 48.2a shows a T1a wide base raised rectal neoplasm measuring 27 mm in width. The wall layers of the rectum are preserved and suggest a lack of invasion. True assessment of invasion is based on pathologic evaluation of the lesion looking for the extent of invasion into the lamina propria, vascular or lymphatic invasion and tumor grade in the resected specimen. Debate on the need to remove lesions en bloc is based on the difficulty assessing lateral margins and cautery artifact of deeper margins with piecemeal resection techniques discussed below and may be avoided with endoscopic submucosal dissection. EUS is very useful for characterizing intramural lesions in the rectum. Figure 48.2b, c shows a large submucosal lesion with a bulky intramural neoplasm of the deep muscularis propria characteristic of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Smaller intramural lesions are more commonly rectal carcinoid tumors. EUS is helpful in determining size but endoscopic resection method is a better predictor of complete pathologic response than EUS findings [11].

Fig. 48.2

Endoscopic ultrasound images. (a) T1a wide base raised rectal neoplasm measuring 27 mm in width. (b) A large submucosal lesion seen on routine endoscopy in the rectum. (c) The lesion measures 3.1 × 1.9 cm and fine needle aspiration revealed features of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) with immunohistochemical stain positive CD 117

48.4 Endoscopic Resection Techniques

Most lesions limited to the mucosa and neuroendocrine tumors can be successfully removed with a diagnostic flexible endoscope using a variety of devices passed through the accessory channel. Treatment of rectal neoplasms with flexible endoscopes has several advantages over transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM). A diagnostic endoscope measures approximately 11 mm in diameter compared to the average operating rectoscope measuring 40 mm. Using the gastroscope provides a shorter device that improves control and reduces time and effort compared to the colonoscope length devices. Most patients having endoscopic resection do well with monitored anesthesia in the deep sedation state compared to general anesthesia for TEM. Candidate lesions for endoscopic resection are listed in Table 48.1. TEM is still the preferred choice for neoplasia with deep submucosal or muscularis propria invasion is suspected if patient characteristics dictate a local excision over traditional anterior resection because TEM allows full thickness resection and closure using proven microsurgical techniques. To date, endoscopic closure techniques are limited to smaller defects and are cumbersome to employ. TEM is also preferred for lesions involving a significant portion of the squamocolumnar junction in the anorectal lumen although ESD has been successful for early stage squamous cell carcinoma within the anal canal [12].

Table 48.1

Rectal neoplasms amenable to endoscopic therapy

Epithelial neoplasms |

Adenomatous polyps |

Serrated adenomatous polyps |

Malignant rectal polyp without stalk or submucosal invasion |

Giant hyperplastic polyps |

Subepithelial neoplasms |

Rectal neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors |

Informed consent should outline the decision to pursue endoscopic resection over surgical weighing the risk of incomplete resection and major complications of endoscopic approach to the immediate risks of full thickness surgical resection (leakage, infection, loss of bowel function and general anesthesia). The most common risk of endoscopic resection is delayed bleeding 2–12 days following resection. We schedule complex endoscopic procedures with monitored anesthesia assistance so that the endoscopist can solely focus on the resection task. Dedicated assistance with proper training must demonstrate patience and share the goal of complete resection at the time of the first procedure no matter how long it takes because subsequent sessions will encounter fibrosis at the resection site, which reduces the effect of future resections and increases the risk of perforation.

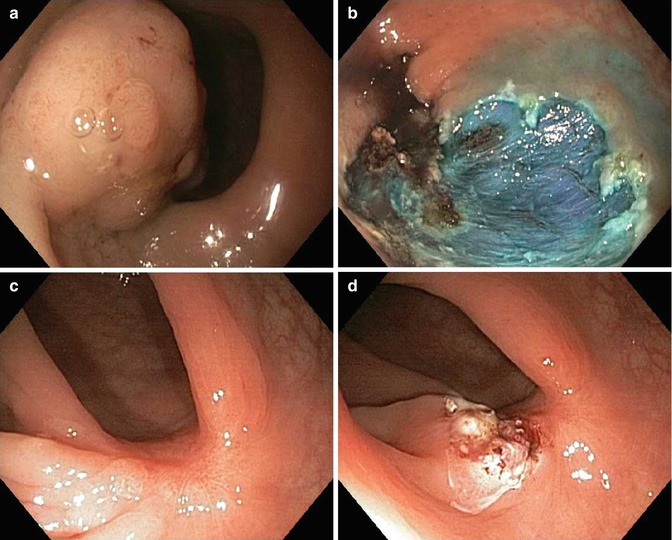

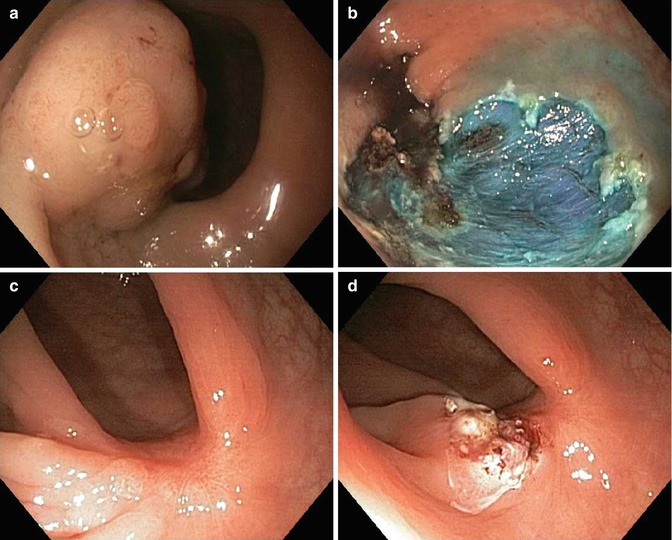

Conventional Polypectomy

Standard or conventional polypectomy for mucosal lesions using a electrocautery snare is considered the major technical advance since the advent of flexible fiber optic imaging. Progression of the technique into wide area endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) refers to piecemeal resection with a submucosal injection when the lesion cannot be completely grasped in total by a routine cautery snare. The submucosal injection was first described by Rosenberg before fulguration of rectal and sigmoid polyps with a transanal approach [13]. Injection into the submucosal plane has now become standard of care throughout the gastrointestinal tract with the advent of flexible endoscopic needle-tip catheters making polypectomy safer and easier. A more recent advance includes tinting the saline solution with a pigment such as indigo carmine to color the submucosal layer blue to improve visibility of that tissue plane (Fig. 48.3). Submucosal injection can obscure the peripheral margins of the lesion, therefore, marking the margins with the tip of the closed electrocautery snare can delineate the area to be resected prior to resection. On the other hand, identification of the margins in very subtle flat colorectal neoplasms is often improved after injection of indigo carmine tinted submucosal saline. We find the later to be more common with flat serrated adenomas due to their hyperplastic appearance.

Fig. 48.3

Endoscopic mucosal resection. (a) A 40 mm adenoma 0-Isp granular lesion at the rectosigmoid junction. (b) EMR site cleared of all neoplasia and reveals blue residual submucosal layer. (c) EMR site healed at 3 months with central scar. (d) Biopsy and focal electrocautery treatment of any suspected residual adenoma; only hyperplastic change noted on specimens

A colloidal additive (succinylated gelatin or hyaluronic acid) can improve the sustainability of the submucosal injection and facilitate wide area piece meal resections compared to saline by reducing the number of injections, resections and procedure time [14]. Other agents such as artificial liquid tears (hypromellose 2.5 % solution) and intravenous volume expanders (hydroxyethyl starch) are more widely available with similar effect. In an excellent review of wide area endoscopic resection techniques of colonic neoplasia, Holt and Bourke recommend intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis and a long acting local anesthetic can be added to the injection solution for resection of advanced neoplasia of the anorectal junction [15].

In piecemeal resection of large polyps, elevate only a portion of the lesion to facilitate capture with the electrocautery snare. Choose the most difficult area first and reposition the patient if needed to achieve a 6 O’clock position with the endoscope. The addition of a friction fit cap to the endoscope tip allows capture of the tissue with application of suction. One cap technique uses a crescent-shaped snare perched at the outer rim and another technique uses a variceal band elastic ligature followed by routine snare cautery. A shorter version of the friction fit cap is commonly utilized to improve visualization during mucosal resection by maintaining a minimum focal length between the mucosa and the endoscope optical lens. Without the cap, positioning of the endoscope is more difficult to maintain endoscopic view especially in angulated and uneven topography. Invasive lesions are difficult to differentiate from fibrous tissue from chronic mucosal prolapsed or prior interventions because both can limit the submucosal injection lift especially at the central portions of the lesion. These clinical situations may be best treated with further advancement in endoscopic submucosal dissection technique.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree