Staging of duodenal FAP

No

(A)

Size (mm)

(B)

Histology

(C)

Dysplasia

(D)

Score points

Stage

Σ score points

<10

<5

Tubular

Low-grade

1

0

0

10–20

5–10

Tubulovillous

Low-grade

2

I

1–4

>20

>10

Villous

High-grade

3

II

5–6

Score = sum of points for criteria A to D.

III

7–8

IV

9–12

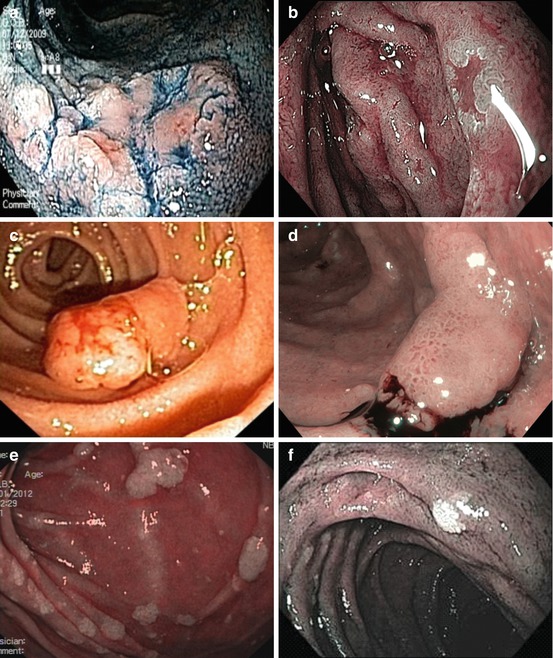

Hamartomatous polyps in PJS harbour a low risk of malignant conversion [9, 13]. However, the risk of complications (e.g. small bowel invagination) increases with polyp size. Therefore, a recent series has successfully performed polypectomy or EMR during double-balloon enteroscopy [13]. In PJS, the extent of small bowel polyposis is usually diagnosed with CT enteroclysis or entero-MR imaging (to avoid radiation exposure) and wireless capsule endoscopy (Fig. 9.1a, b).

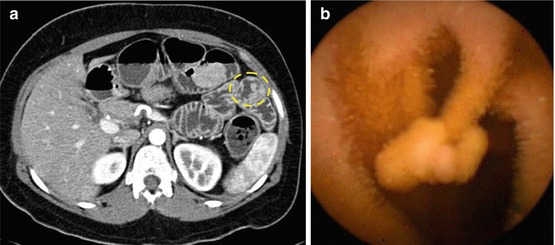

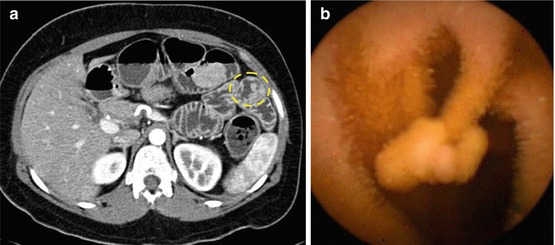

Fig. 9.1

(a) Computerized enteroclysis tomography of jejunal polyp type 0-Ip (circle). (b) Wireless capsule endoscopy image of jejunal polyp type 0-Ip

Note

In patients with FAP and duodenal adenomatosis, we recommend the following:

Downstaging of Spigelman stage II and III by cold snaring of multiple small adenomas

EMR of larger-size (>10 mm) or advanced adenomas (with LGIN, HGIN) by endoscopists experienced in duodenal endoscopic resection

9.3 Ampullary Adenomas

Peri-ampullary/ampullary adenomas involving the major duodenal papilla are usually diagnosed because of symptoms or parameters of cholestasis or pancreatitis. These neoplasias occur sporadically or genetically (in FAP). In both conditions, cancerous transformation is more frequent than for non-ampullary adenomas and ranges from 26 to 65 % [14].

Duodenoscopic imaging of microsurface and microvascular structure has not systematically been analysed in ampullary neoplasias. Evaluation of adenoma vs. adenocarcinoma mainly relies on macroscopic signs of malignancy – such as firmness, ulceration, and friability – and targeted biopsy. The extent and local spread of tumour including lymph node involvement is best staged with 7.5 MHz endoscopic ultrasound as well as with ERCP and intraductal ultrasound (IDUS, 20 MHz) to map the extent and intramural invasion of the tumour as well as extension in bile duct and pancreatic duct. Endoscopic snare papillectomy (or ESD) is preferred for adenoma/focal differentiated adenocarcinoma with inconspicuous regional lymph nodes and without evidence of submucosal invasion, extending for less than 10 mm into the bile duct [15, 16]. Staging of pT category in en bloc specimens reveals whether resection was curative. More advanced ampullary cancer requires surgical en bloc resection [15, 17].

9.4 Endoscopic Analysis of Small Intestinal Lesions

The standardized approach for non-ampullary duodenal lesions uses a prograde viewing HD gastroscope with magnifying NBI (60-fold), the patient in left lateral or dorsal decubitus position, and application of butyl-scopolamine to inhibit peristalsis. Side-viewing endoscopy and indigo carmine CE −/+NBI may approximately double the detection rate of duodenal adenomas [18].

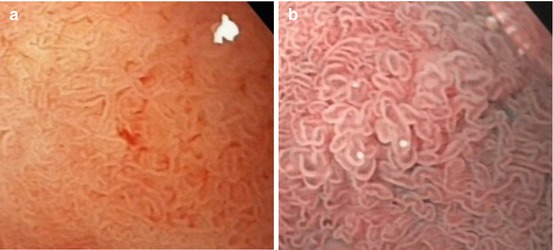

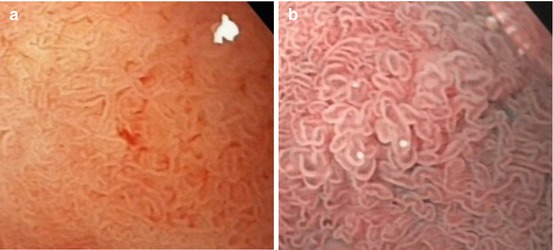

Normal mucosa shows microsurface pattern (MSP) of villous intestinal columnar epithelium – often with minor islets of gastric metaplasia (fundic-type pit pattern) – in the duodenal cap (duodenum part 1) and fine villous surface pattern with spiral microvascular pattern in part 2 (descending part) (Fig. 9.2a, b) and part 3 (horizontal part) of the duodenum and in the jejunum.

Fig. 9.2

Mucosa in the descending duodenum: small bowel villi, intestinal cylinder cell-lined epithelium. (a) Magnifying WLI (60× magnification) and (b) m-NBI (80×)

9.4.1 Differential Diagnosis of Non-neoplastic vs. Neoplastic Non-ampullary Mucosal Lesions in the Small Bowel

Protruding lesions in the small bowel, in particular the duodenum, have a wide differential diagnosis. Endoscopic analysis of the lesions usually needs confirmation by targeted biopsy and occasionally further workup with high-resolution EUS (20 MHz) or for submucosal tumours type 0-Is/Isp linear array EUS (7.5 MHz) and fine needle puncture biopsy. Carcinoids and neuroendocrine tumours of size larger than 10 mm require scintigraphic and radiological staging. The differential diagnosis and management recommendations for protruding duodenal lesions [6] are listed in Table 9.2.

Table 9.2

Differential diagnosis and management of sporadic non-ampullary protuberant (0-Isp or 0-IIa) duodenal lesions [6]

Classification | Histology | Management | Surveillance |

|---|---|---|---|

Epithelial | Gastric metaplasia | None | None |

Adenoma−/+HGINa | Endosc. resection | 6–12 months | |

Carcinoma T1ba | Surgical resection | Stage-dependent | |

Submucosal | Inflamm. fibroid ~ | ? Endosc. resectionb | None |

Lipoma (symptomatic) | ? Resect. (endo/surg)b | None | |

Leiomyoma | ? Resection (surg) | None | |

Carcinoid | Resection (endo/surg) | Stage-dependent | |

GIST | Resection (surg.) | Stage-dependent | |

NET | Resection (endo/surg) | Stage-dependent | |

Hamartoma | Brunner’s gland ~ | ? Endosc. resectionb | None |

Peutz-Jeghers ~ | Endosc. resectionb | See PJ syndrome | |

Lymphoma | MALT or T cell ~a | Particle biopsy | Stage-dependent |

Protruding mucosal neoplastic lesions in the duodenum and small bowel must be distinguished from non-neoplastic lesions, such as gastric metaplasia (regular fundic-type pits without intestinal villi) (Fig. 9.3a–c), and non-neoplastic submucosal lesions covered by normal duodenal mucosa, e.g. Brunner gland cysts and hamartomas (PJS polyp, juvenile polyp, Cronkhite-Canada polyp, and Cowden’s polyp) [6, 19].

Fig. 9.3

Gastric metaplasia in duodenal cap. NBI observation. (a) Overview, (b) 60-fold magnification, and (c) biopsy scar with regenerative metaplastic epithelium (NBI, 80-fold)

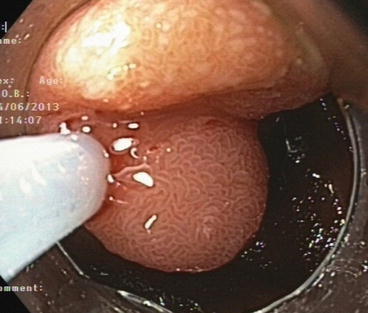

Submucosal tumours (SMT) are usually identified by normal mucosal aspect and bridging mucosal folds (compare Fig. 8.2d). Most frequently, submucosal lesions are carcinoid (Fig. 9.4) as well as other neuroendocrine tumours, lipoma, inflammatory fibroid polyp, gastrointestinal stromal tumour, and leiomyoma [6]. Carcinoid and NET exceeding 10 mm diameter carry substantial risk of malignant transformation (proven by Ki-67 labelling index >2 %) and metastasis (recent consensus details subclassification with diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines [20]). Low-grade malignant NET or carcinoid should be resected en bloc when size is ≤10 mm using ESD or complete circumferential mucosal incision of the lesion completed by snaring – or by surgery [20].

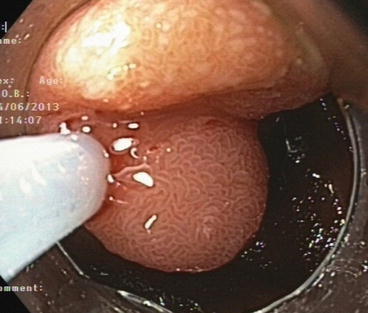

Fig 9.4

Submucosal tumour (NET G1, 12 mm) in horizontal duodenum (part 3). EMR en bloc (R0). Normal villous surface epithelium is evident (WLI, magnification 40×)

Sporadic non-ampullary adenomas most often present on WLI as whitish lesion (~80 %) in pale-orange duodenal mucosa and a few as reddish lesion. They show clear margins, most often flat elevated (0-IIa) or sessile (0-Is) morphology and less often (~10–20 %) depressed type (0-IIc, 0-IIa + IIc). The surface is regular flat or granular, and microsurface structure is similar as villous or gyrous colonic pit pattern (PP IIIL or IV). Expression of white zones (WZ) in the gyrous/ridge MSP is more pronounced in the small bowel, and some apparently present dilated lymph vessels enhancing the whitish aspect (Fig. 9.5a–d). The microvascular pattern is dense, similar as in non-protruding colonic adenomas (MVP II or IIIA, compare Table 4.2B) [4, 19, 21–23].

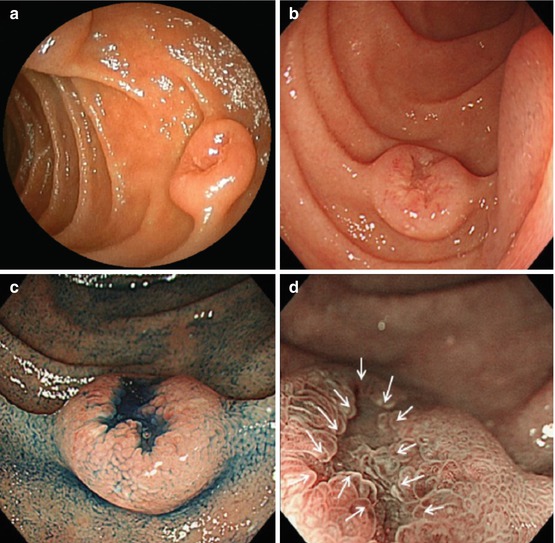

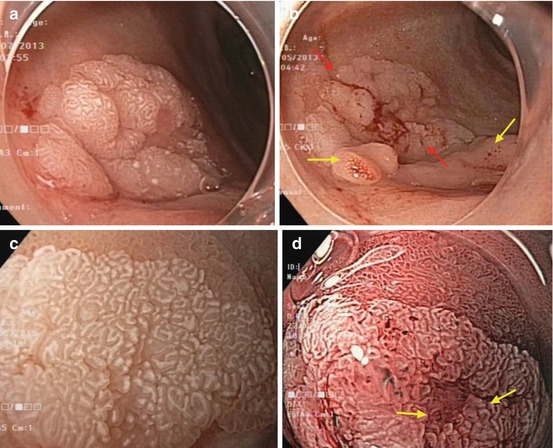

Fig. 9.5

(a, b) Adenoma (red arrows) in duodenal cap (anterior side) and gastric metaplasia (yellow arrows, inferior side). (c) Magnifying WLI (60×) of (a, b). Adenoma in duodenal cap (ventral margin) and villous duodenal mucosa (top). Note: enhanced and even white zone of crypt epithelium (also hiding microcapillaries) and distinct clear margin. (d) Duodenal adenoma with biopsy scar (arrows). Note: enhanced white zone of marginal crypt epithelium and regular microcapillaries (spiral, open loop), magnifying NBI, 80× (same adenoma as in a, b)

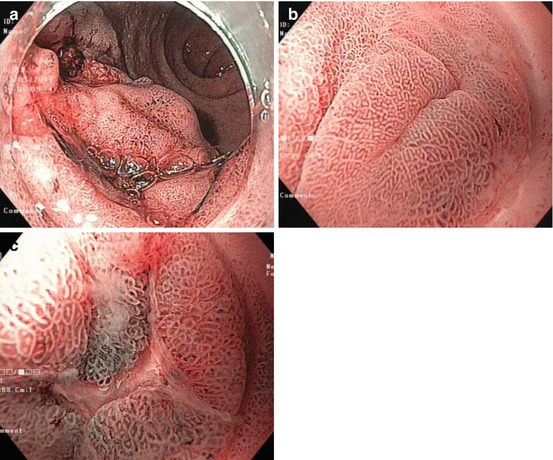

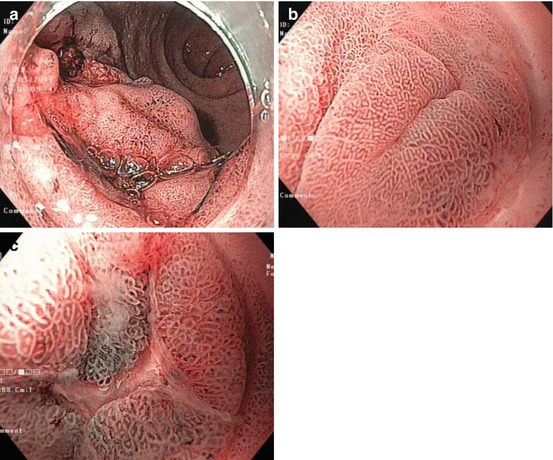

In FAP, non-ampullary adenomas present the same morphology, MSP, and MVP as sporadic adenomas, but there usually are multiple duodenal lesions [5, 8, 11] (Fig. 9.6a–f, Table 9.1). In a prospective study of progression of duodenal polyposis based on the modified Spigelman score, the estimated cumulative risk for stage IV duodenal polyposis was 43 % at age 60 years and 50 % at age 70 years [8]. The rate of advanced adenocarcinoma was 36 % within a median of 8 (4–10) years for Spigelman stage IV disease [5].

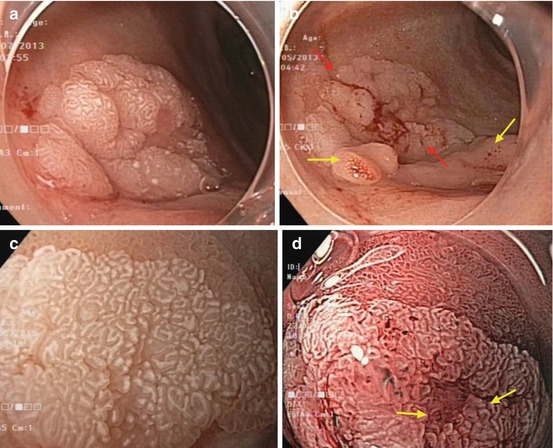

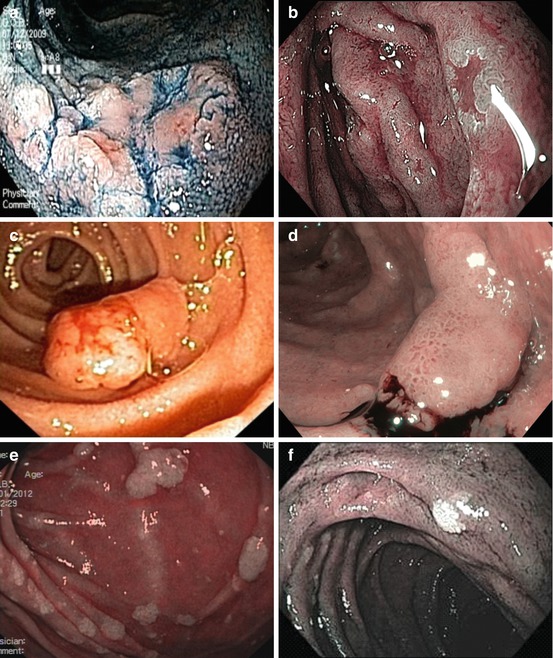

Fig. 9.6

Non-ampullary duodenal adenomas in FAP. (a) Flat type 0-IIa + c (indigo carmine, WLI). (b) Depressed type 0-IIc (NBI). (c) Sessile type 0-Isp (ordinary WLI). (d) Sessile type 0-Is in duodenal adenomatosis (NBI, after targeted biopsy). (e) Duodenal adenomatosis (multiple 0-IIa) (NBI). (f) Flat type 0-IIb, whitish (NBI), FAP patient (e) 6 months after cold snaring

9.4.2 Differential Diagnosis of HGIN/Superficially sm-Invasive Carcinoma vs. Deep sm-Invasive Carcinoma in the Small Bowel

Evidence-based prospective studies on microsurface and microvascular patterns are not available for small bowel neoplasias. Larger-size (>20 mm) and reddish-appearing adenomas type 0-IIa more likely harbour HGIN [4] (Fig. 9.6c). Distinct depressed 0-IIa + IIc morphology may be associated with higher probability of HGIN or intramucosal adenocarcinoma, in particular when the depressed area presents irregular MSP and MVP similar as colonic pit pattern types IIIs or Vn and MVP IIIA [19, 21, 24] (compare Table 10.3). Moreover, central dimpling or depression with nonstructured MSP and MVP heralds sm-invasion of cancer [25] (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8). Non-lifting upon submucosal injection signals massive sm-invasion (>sm1) or severe sm-fibrosis beneath the protruding adenoma. The risk of focal carcinoma is increased in villous adenomas [5]. Neoplasias with macroscopic signs of malignancy are rare, e.g. duodenal invasive adenocarcinoma (Fig. 9.8) or mucosal metastasis (e.g. of pancreatic, breast, lung cancer).