, Mark Thomas1 and David Milford2

(1)

Department of Renal Medicine, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, UK

(2)

Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham, UK

Abstract

In this chapter we explain:

How kidney disease develops in people with diabetes

How vascular disease can affect the kidneys

The effect of chronic infection and inflammation on the kidneys

Many diseases affect the kidneys as one part of a multisystem illness. They are included throughout the book and can be located using the index. Immune-mediated diseases are described in Chap. 14.

In this chapter we focus on the most common long term conditions that affect the kidneys – diabetes, atherosclerosis, and chronic infection and inflammation.

Diabetes Mellitus

The prevalence of diabetes worldwide is growing at an alarming rate. The rise has been almost exponential in the UK and the prevalence is likely to get worse as the obesity epidemic continues (Fig. 5.1).

Fig. 5.1

The rising prevalence of diabetes in the UK over the last 70 years. Numbers of people affected (Data from various sources)

Kidney involvement in diabetes is common; about 25 % of people with diabetes in England have proteinuria [1]. Although only 0.5 % has end-stage kidney failure, this percentage has more than doubled between 2004 and 2010. Diabetes is the commonest cause of chronic kidney disease; in some countries such as the US and Germany, up to half of patients with CKD attending nephrology clinics have diabetes.

The natural history of diabetic nephropathy typically progresses from microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria and then to a decline in GFR. GFR increases in the initial stages of nephropathy and this hyperfiltration may accelerate damage to the glomeruli and increase albuminuria (see Fig. 5.2) [2].

Fig. 5.2

The natural history of early diabetic nephropathy. There is steadily increasing albuminuria. GFR initially increases – ‘hyperfiltration’ – and then declines

In more advanced disease, there is progressive sclerosis of glomeruli and the GFR declines, usually with a linear trend. The slope varies between patients, those with heavy proteinuria tending to decline more rapidly (see Fig. 5.3).

Fig. 5.3

The natural history of diabetic nephropathy showing hyperfiltration followed by heavy proteinuria and a decline in GFR to end stage kidney failure

Two factors increase the risk of someone with diabetes developing nephropathy – poor glucose control and high blood pressure . Achieving glucose control is particularly important in the first few years after diagnosis as this can leave a legacy of reduced risk in future years. Control needs to be achieved before albuminuria is established. In type 1 diabetes, the risk of reduced kidney function is halved by tight glucose control in the early years [3]. In type 2 diabetes, controlling blood glucose prevents the development of albuminuria but has no clear effect on the rate of decline in GFR [4]. Over-aggressive glucose control may be harmful. Intensive glucose treatment in people with kidney disease, even CKD stage 1, increases the risk of mortality by 30 % [5].

Patient 5.1: Glucose Control Does Not Protect Against Loss of GFR

Andrea had type 1 diabetes since she was 8 years old and struggled for many years to control her blood glucose. In early 2013, aged 23 years, she attended a diabetes education course where she learned how to estimate her insulin needs and adjust the dose accordingly.

Her blood glucose control improved dramatically, as shown by the fall in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c). Despite this, her GFR continued to decline (Fig. 5.4).

Fig. 5.4

Decline in GFR despite marked improvement in glucose control (HbA1c). 100 mmol/mol = 11.3 % DCCT. 50 mmol/mol = 6.7 % DCCT

With better treatment, especially using inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, outcomes in diabetic nephropathy have improved substantially in recent years [6]. Albuminuria can often be reduced, with microalbuminuria sometimes remitting completely [7]. Even patients with nephrotic-range proteinuria can benefit considerably from these drugs (see Patient 5.2).

Patient 5.2: The Effect of ACE Inhibition on Diabetic Nephropathy

Mr Archer had neglected his type 1 diabetes over many years and had failed to attend the diabetic clinic for long periods. He had developed peripheral and autonomic neuropathy, and suffered from postural hypotension and severe nocturnal and gustatory sweating.

He was persuaded to attend clinic by his partner who was increasingly concerned about his health. His blood pressure was high when seated (164/84) but low when he stood up (90/54). He had very swollen legs, nephrotic-range proteinuria (protein:creatinine ratio = 1148 mg/mmol) and hypoalbuminaemia (21 g/L); in other words he had the nephrotic syndrome. His eGFR had dropped considerably compared to the result 2 years earlier (Fig. 5.5).

Fig. 5.5

Rapid decline in GFR, 30 ml/min/1.73 m2/year, and drop in serum albumin due to diabetic nephropathy with nephrotic syndrome

Because of the apparent suddenness of these complications, a renal biopsy was performed.

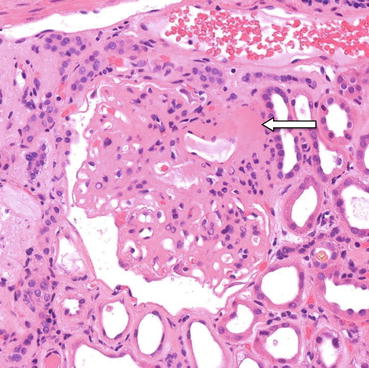

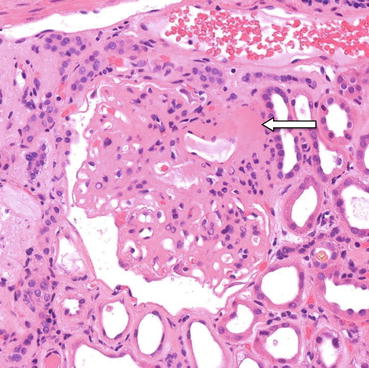

It showed typical features of diabetic nephropathy (Figs. 5.6 and 5.7).

Fig. 5.6

Typical changes of diabetic nephropathy: diffuse glomerulosclerosis and hyalinosis. The walls of the glomerular capillaries are thickened and the mesangium is expanded. There is a nodular deposit of hyaline material at the vascular pole of the glomerulus (arrow). Haematoxylin and eosin ×200

Fig. 5.7

Diffuse glomerular sclerosis of diabetes with Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules, thickening of the glomerular basement membrane and focal hyalinosis. Silver ×200

The ACE inhibitor ramipril was started, at a modest dose of 5 mg daily. He had not previously taken this class of drug.

Over the following month, the rate of loss of albumin in his urine reduced to levels that could be matched by synthesis in his liver. As a result his serum albumin returned to normal, i.e. he was no longer nephrotic.

The rate of decline in his eGFR slowed dramatically, from 30 ml/min/1.73 m2/year to 8 ml/min/1.73 m2/year (Fig 5.8).

Fig. 5.8

Slowing in the rate of decline in eGFR to 8 ml/min/1.73 m2/year with restoration in serum albumin to normal with ACE inhibitor treatment started in 2011

He eventually reached end-stage kidney failure and had a combined kidney and pancreas transplant, which transformed his health.

Atherosclerosis

Patients with cardiovascular disease, such as angina, myocardial infarction or stroke, are likely to have atherosclerosis affecting the renal arterial circulation. There may be a stenosis of one or more renal arteries or diffuse narrowing of the intrarenal arterial tree (see Figs. 5.9 and 5.10).