small groups. He postulated that they arose from the epithelium in which they were found, which in the case of the GI tract was the endoderm.

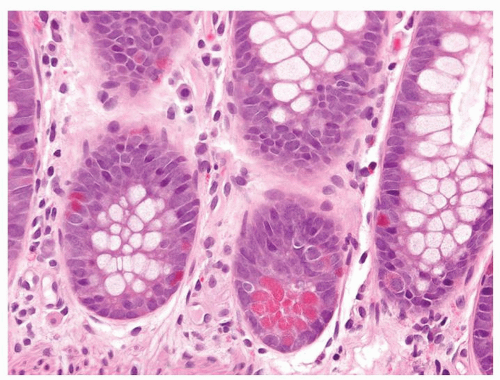

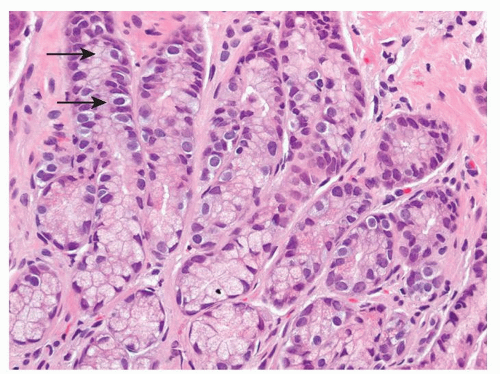

Figure 5-2. Endocrine cells with clear cytoplasms (arrows) surrounding the nuclei along the sides of the gastric glands and necks. |

subdivide them based on the degree of differentiation (Table 5-1).23 Table 5-2 lists the tumors described in the endocrine tumor chapters in the various sites. The more common of the endocrine tumors by far is the low-grade, highly differentiated neoplasm, generically referred to as a carcinoid tumor. Then, there are a variety of gastrointestinal carcinomas that contain different amounts of an endocrine cell component, which varies from single cells scattered about to large areas of endocrine differentiation. These have been given different names but are best considered adenocarcinomas with variable endocrine differentiation. The carcinoid tumors differ by site, by their products, and by their prognosis. In contrast, the small and large cell endocrine carcinomas have little site-dependent variability, and prognostically they are much the same regardless of site.

Table 5-1 Classification of Endocrine Tumors in the Gastrointestinal Tract | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 5-2 Endocrine Tumors in the Gastrointestinal Tract and Their Distribution | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

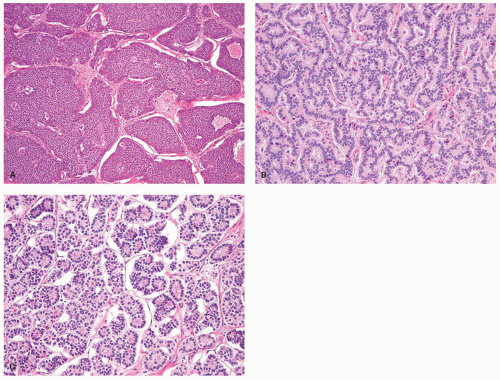

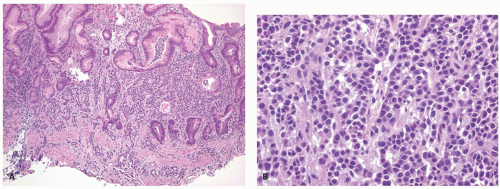

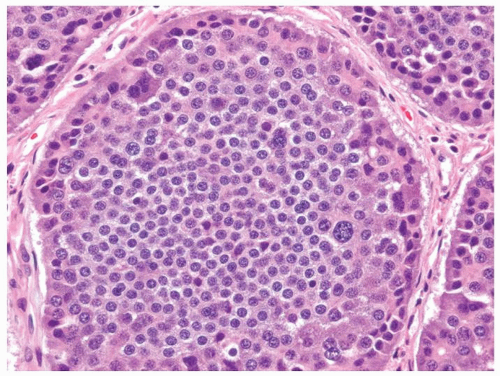

the pituitary, the parathyroid glands, and the islets of Langerhans. Regardless of the sites in which they arise, they are composed of much the same type of bland-appearing cuboidal cells or short columnar cells that are, in general, remarkably uniform, except for a few nuclei that may be slightly bigger than their neighbors, or occasional cells that may have more fine cytoplasmic granules than do other cells (Fig. 5-3). Mitoses are usually infrequent. Most tumors have little or no necrosis. The only histologically interesting aspect is that these uniform cells are arranged in several patterns, including in large nests referred to as the insular pattern, in ribbons of cells that often interconnect; and in tubules or glands in which the cells are arranged around small lumens (Fig. 5-4). Certain growth patterns are more common in certain tumor locations, although there is considerable overlap among sites. Thus, although ileal tumors usually have the nest or insular pattern, every so often the cells are arranged in ribbons or tubules. Most textbooks and published papers also spend a lot of words describing the growth patterns of carcinoid tumors in different sites, with trabecular, glandular, or insular patterns occurring in this or that site, but these differences are not important in clinical practice. If we see a carcinoid tumor of the small intestine that has a trabecular growth pattern when the literature tells

us it is supposed to have an insular pattern, will we panic or deny its existence because it is growing the wrong way? Of course not! We will accept this aberrant growth pattern and wonder what it means in terms of behavior or treatment, or if it is an unusual cell type. In this chapter, we will spend few words about growth patterns. The carcinoid tumors differ from one site to another in the background mucosa in which they arise, in their relation to other hormones on which their constituent cells are dependent, and in the substances they produce.

Figure 5-3. Carcinoid tumor (well differentiated NET) with a large nest containing mostly uniform cells except for occasional cells with larger nuclei. |

the appendix identified by marking with ink as the surgical margin in every appendectomy. Submitting the margin is helpful in making important immediate recommendation for further resection when a tumor is unexpectedly identified. This is especially important if the tumor is identified on retrospective review of slides and the gross specimen has already been discarded. Spread into the mesoappendix, which is also potentially a resection margin, infrequently occurs, although this is more likely to be relevant in the goblet cell carcinoids, which are covered in the appendix chapter.

that while measuring the two dimensions of a lesion on the slide is not problematic, constructing the three dimensions of a tumor is inaccurate, especially when dealing with measurements in millimeter range. This almost implies that the entire appendix has to be submitted for histology, the cross sections of the appendix have to be submitted in some form of sequence, and tissue blocks have to be exactly of the same thickness.

As a result, there is little important information that has accumulated about esophageal carcinoid tumors.30, 31 The few that have been reported are in the lamina propria and deeper, and they look like carcinoid tumors elsewhere, although some of them have been reported as atypical or malignant carcinoid tumors. They tend to produce single lumps or masses, but some of them have been found in association with Barrett’s mucosa, even as separate foci adjacent to invasive Barrett’s adenocarcinomas. In fact, it is possible that the Barrett’s setting is more common than the sporadic setting. It appears that some of the reported cases are not typical carcinoid tumors with uniform cells and nuclei, but atypical forms or even small cell carcinomas. So the esophageal carcinoid literature may be contaminated with other tumors. There is little long-term follow-up information, so it is impossible to get hard data about metastases, survival, and features of the tumors that correlate with adverse outcome. However, the limited published data suggest that esophageal carcinoid tumors are likely to have a favorable outcome, but survival seems to be stage related and possibly also related to whether they are histologically typical carcinoids or if they have atypical features, such a pleomorphism, mitoses, or necrosis. They do not make anything that results in any clinical syndrome.

Table 5-3 Gastric Enterochromaffin-like Cell (ECL-Cell) Carcinoid Tumors Subtypes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

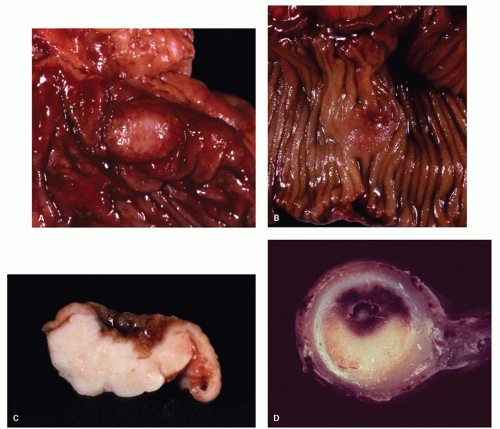

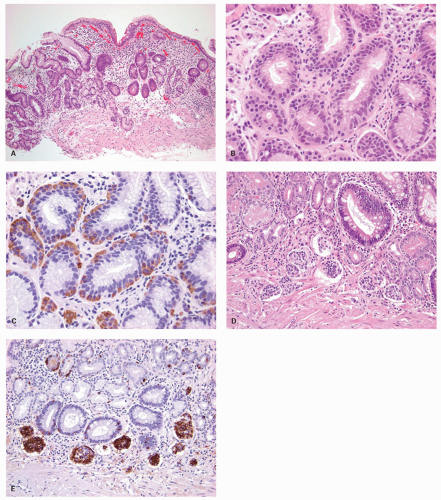

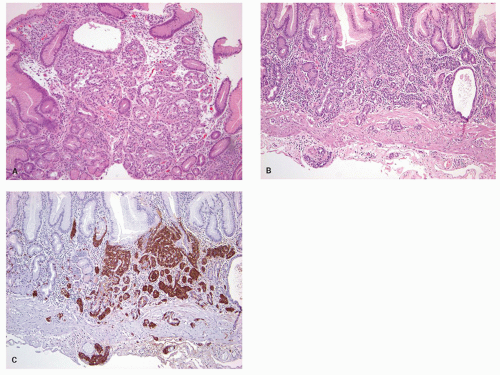

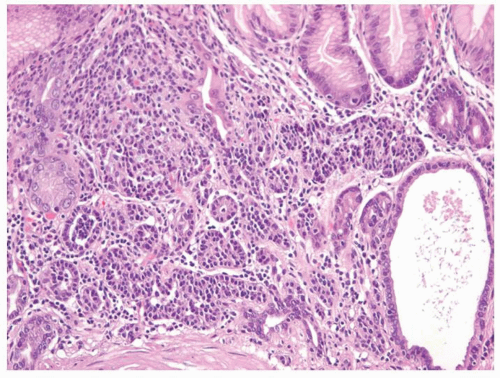

carcinoids. Thus any generic discussion of gastric carcinoid tumors is likely to be heavily weighted toward these type I tumors. This number is likely to increase as more cases of unsuspected autoimmune gastritis are uncovered as a result of increasing upper endoscopy. At what point is an ECL-cell proliferation considered to be a carcinoid tumor? There are some seemingly arbitrary definitions that simplify this issue, which are listed in the WHO book on tumors of the digestive system.33 First, there is a phase referred to as “dysplasia” in which the cells become relatively atypical and the nodule enlarge and fuse with micro-invasion of newly formed stroma (Fig. 5-7). Then, when the nodules reach a size larger than 1/2 of a millimeter or

invade into the submucosa, they are classified as carcinoid tumors/NETs (Figs. 5-8 and 5-9). Type I tumors are invariably asymptomatic, commonly multiple, and small and often microscopic. These tumors tend to be easily treatable by local endoscopic excision if large or forming an endoscopic polyp, or by simple follow-up to ensure tumors are not enlarging, which is rarely seen, with a generally excellent outcome. They rarely metastasize, probably because they are not large enough when we find them. Only when a tumor reaches about 2 cm across, is metastasis a concern and type I tumors of this size are rare. Lymph node metastases from these tumors are rare, and deaths almost unrecorded.

Figure 5-7. ECL-cell dysplasia: Multiple nodules, some fused, and apparently invading lamina propria. |

examined for autoimmune gastritis. Unfortunately, in most such situations, the endoscopists usually only biopsy the small polyp and the status of the adjacent mucosa remains unknown. In such cases, the pathology report should discuss this issue that there is insufficient adjacent mucosa to tell if the carcinoid is arising in autoimmune gastritis, and that this determination is critical for patient management. Often, a repeat upper endoscopy is required to sample the flat body mucosa from greater curvature, lesser curvature, and incisura. Surprisingly, antral biopsies can also be of value in showing a G-cell hyperplasia in atrophic gastritis, but usually no G-cell hyperplasia when there is a gastrinoma; however, antral biopsies alone in the absence of sampling from the body mucosa are insufficient to render a diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis. The presence of Helicobacter or extensive multifocal atrophy with metaplasia might indicate current or prior H. pylori infection. An ancillary test is serum gastrin, which in these patients is very high, excluding the diagnosis of sporadic (type III) carcinoids; however, one should ensure that the patient is off any proton pump inhibitors for sufficient time before measuring serum gastrin levels.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree