excretion of viral particles in the days prior to clinical symptoms and continuing through to its resolution. Rotavirus is a seasonal infection and in temperate climates infections peak during the winter months3. In bacterial enteric infection transmission can be through contaminated water or foodstuffs.

Table 3.1 Main agents of infectious acute diarrhoea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

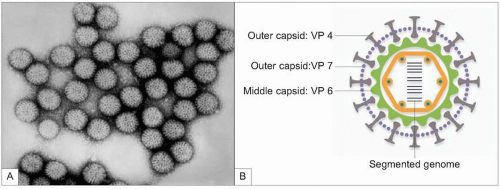

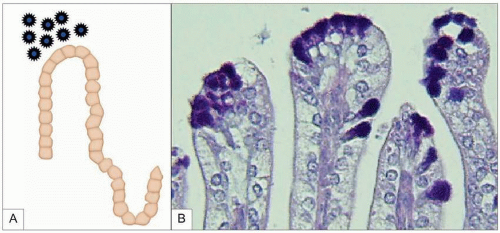

Table 3.2 Main features of viral agents | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

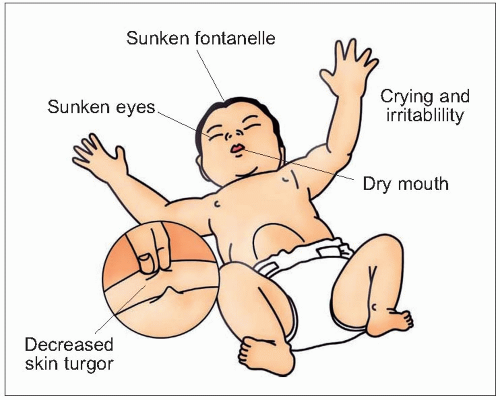

Table 3.3 Clinical features suggestive of bacterial diarrhoea | |

|---|---|

|

|

include stool cultures for bacteria and detection of faecal viral antigen by enzyme immunoassay (EIA), agglutination with latex particles, or immunochromatography.

|

Table 3.6 Recommendations for faecal laboratory study | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

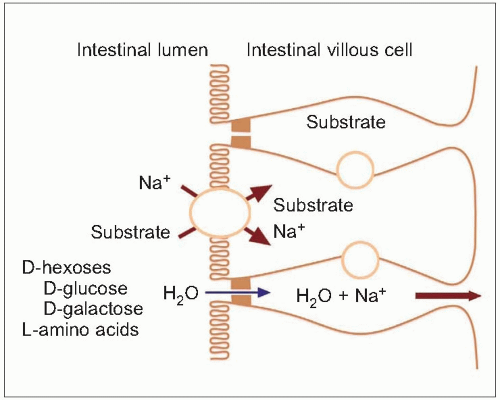

Table 3.7 Oral rehydration solution composition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree