- Indications to commence dialysis are:

- intractable hyperkalaemia;

- acidosis;

- uraemic symptoms (nausea, pruritus, malaise);

- therapy-resistant fluid overload;

- chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 5.

- intractable hyperkalaemia;

- There is considerable variation of the level of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) individuals may tolerate before becoming markedly uraemic.

- ‘Crash-landing’ onto dialysis confers a reduction in patient survival that persists for at least the first three years of subsequent therapy.

- Early identification and assiduous preparation mentally and physically are needed in the predialysis phase for those likely to need renal replacement therapy (RRT).

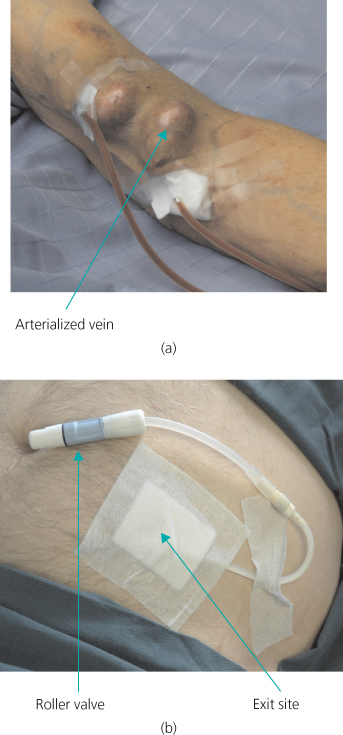

- Haemodialysis (HD) involves circulating blood through a disposable dialyser. The vascular access of choice is the arteriovenous fistula (AVF). This, however, requires suitable peripheral veins and needs four to eight weeks for the fistula to mature. If there are no suitable veins, a graft can usually be inserted. Acute access with venous catheters has a high complication rate.

- Peritoneal dialysis (PD) involves using the peritoneum as the dialysis membrane, with pre-packaged fluid being instilled into the peritoneal space via a Tenckhoff catheter. This is usually only inserted once the decision to start dialysis is made.

- HD is usually performed in four-hour sessions, three times a week, in hospital-based dialysis units.

- PD typically involves continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), which allows continuous dialysis using three to five exchanges of fluid per day via disposable bags.

- Automated peritoneal dialysis (APD), whereby larger volumes of fluid are instilled and drained by the use of a small machine by the bedside, is used when either more intense dialysis is needed or when, for social reasons, the night is the preferred time for treatment.

Introduction

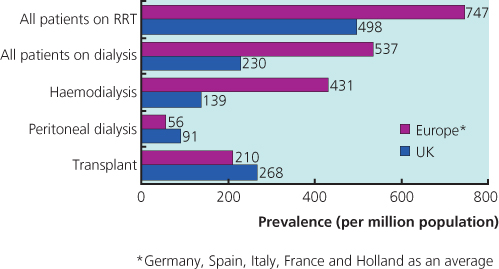

Thomas Graham described the founding principles of dialysis over 100 years ago. Even though the first treatments for acute kidney injury (AKI) were performed in the 1920s, chronic dialysis treatment for end stage renal failure (ESRF) did not become a reality until 1960. In the following few years, a series of breakthroughs in both dialysis technology and vascular access enabled chronic renal replacement therapy (RRT) to become established in both the United States and Europe by the mid-1960s. Chronic haemodialysis (HD) became widely available in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s (largely as a home-based therapy), and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) became increasingly popular during the early 1980s. There are now over 2.0 million patients receiving regular dialysis worldwide and around 36,000 in the United Kingdom alone (Box 10.1 and Figure 10.1).

- The most common cause of end-stage renal disease is diabetic nephropathy

- Demand for dialysis will continue to increase over the next 10 years by as much as 150% for HD

- The minimum estimated prevalence of RRT in the United Kingdom at the end of 2003 was 632 patients per million population

- Of new patients, 22% starting RRT are >75 years old and 12% of all prevalent patients are >75 years old

- In 2003, 67.5% of RRT patients received HD and 29.2% PD (3.3% had a transplant)

- The average cost of dialysis is £30 000 per patient per year

- The cost of a kidney transplant is £20 000 per patient per transplant with immunosuppression costs of £6500 per patient per year

- Mortality rate in dialysis patients is about 20% annually

- Commonest cause of death is cardiovascular disease, the risk of which is 30 times higher in dialysis patients than age-matched controls

Indications for Starting Renal Replacement Therapy

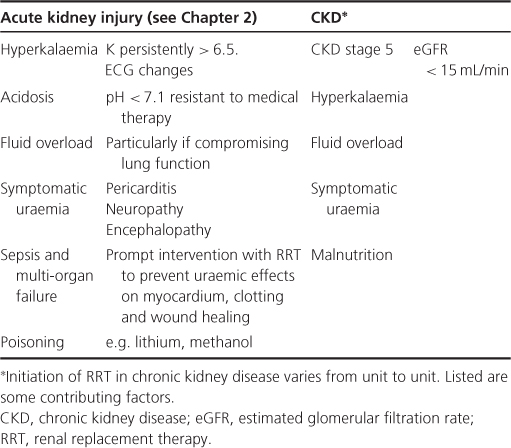

There is relatively little difference in opinion about intractable hyperkalaemia, acidosis, uraemic symptoms (nausea, pruritus, malaise) and therapy-resistant fluid overload being firm indications to commence dialysis. There is, however, wider variation in clinical practice as to when to start a relatively asymptomatic patient. A cut-off based on measured or calculated GFR may be applied. In general, this would be set in the CKD stage 5 range (estimated GFR ∼10–15 mL/min). The advantages of such a ‘well start’ are multiple, and allow for maintenance of health prior to the development of significant abnormalities in either overall function or body composition. Furthermore, it allows dialysis provision to be built up slowly to compensate for further reduction of residual renal function (RRF). There is, however, still no robust (randomized controlled) evidence-base for such an approach. It is important to note that there is considerable variation in the level of GFR individuals may tolerate before becoming markedly uraemic. This may necessitate even earlier starts. The potential price for later initiation is that sudden decompensation may occur, requiring emergency treatment and a ‘crash-landing’ onto dialysis. This confers a reduction in patient survival that persists for at least the first three years of subsequent therapy.

The general indications for starting dialysis are summarized in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1 Indications for renal replacement therapy

Preparation for Renal Replacement Therapy

Timely and effective preparation for RRT, as well as assiduous management of the complications of CKD, is crucial. Optimal therapy while on dialysis will only partially compensate for previous deficiencies in care, with hypertension, functional/structural cardiovascular disease, malnutrition, parathyroid hyperplasia and renal bone disease already being well established in the predialysis phase. There are a number of key issues, covered below, that require a properly configured multidisciplinary team. They need to be delivered in the most effective and appropriate way regarding an individual’s social and ethnic sensibilities.

Choice of Dialysis Modality (see Chapter 4)

Although there may be certain overriding medical or social imperatives, the choice between peritoneal dialysis (PD) and HD (either unit- or home-based) should be free, and not constrained by either clinician’s prejudice or resource issues. Sufficient time and information must be provided to allow patients and families to make this choice. Poor or compelled choice will result in a higher chance of treatment failure, and poorer long-term outcomes (therapies are summarized in Table 10.2).

Table 10.2 Relative advantages and disadvantages of haemo- and peritoneal dialysis

| Haemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | |

| Methods and procedures | Three 4-hour sessions a week, usually in hospital Some flexibility with days and sessions Not reliant on patient’s ability to learn or carry out procedures | Continuous dialysis using up to four exchanges/day or cycling at night Procedure done at home and can fit more easily into lifestyle and work Reliant upon patient or other person to perform the procedure safely |

| Dialysis access | Acute access with venous catheters has high complication rate (infection, stenosis, thrombosis) Fistulae need 2–3 months to mature before use AV fistulae can be difficult to form in patients with vascular disease | Access relatively easy to establish Can be used immediately Comparatively more contraindications (stoma, bowel adhesions, inoperable hernias, obesity) |

| Fluid balance/ultrafiltration | Set at the beginning of dialysis and is predictable Amount of fluid to be removed is limited by cardiac function (increased risk of intradialytic hypotension) | Less predictable Controlled by concentration of dextrose (or glucose polymer) in dialysate Integrity of the peritoneum as membrane declines with time, esp. with frequent use of higher dextrose concentrations |

| Complications | Catheter infections and associated complications (septicaemia, SBE etc.) can be life-threatening Cardiovascular death from arrhythmias, myocardial infarction and stroke are increased IDH predisposes) | Exit site infections are rarely serious and peritonitis, if persistent, usually resolves after removal of catheter Recurrent infections and membrane failure lead to high dropout rate Hernias and leaks from increased peritoneal pressure |

| Psychosocial considerations | Transport to and from the unit three times a week can disrupt patient and family schedules and prolong dialysis sessions Holidays are hard to plan as patient must rely on local dialysis facilities Body image problems associated with access/fistulae Erectile dysfunction and poor libido | Care of a family member at home can be easier Transport to hospital only needed for clinics or emergencies PD fluids can be delivered worldwide with prior notice Body image problems associated with PD catheter Erectile dysfunction and poor libido |

AV, arteriovenous; PD, peritoneal dialysis; SBE, subacute bacterial endocarditis; IDH, intradialytic hypotension.

Dialysis Access

The vascular access of choice for HD remains the arteriovenous fistula (AVF). This requires the anastomosis of an artery to a suitable segment of vein (usually either at the wrist or in the antecubital fossa). This section of vein receives arterial pressure blood and becomes ‘arterialized’. This results in a structure with a thick wall, readily accessible, and with adequate flow within it to sustain an extracorporeal circuit. If there are no suitable peripheral veins, a piece of synthetic material can be inserted (usually a polytetrafluoroethylene, or PTFE, graft) and this is subsequently needled for access. For the reasons of the time taken for the AVF to mature (4–8 weeks), and an initial failure rate, which may be as high as 30% (especially in older, arteriopathic or diabetic patients), this procedure must be performed in good time (Renal NSF recommends six months in advance of likely need). A Tenckhoff catheter for PD, to allow fluid to be instilled into the peritoneal cavity, can be inserted either at laparotomy, laparoscopically or percutaneously, but usually once the decision to start dialysis has been made (Figure 10.2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>