- Urinary protein excretion of <150 mg/day is normal (∼30 mg of this is albumin and about 70–100 mg is Tamm-Horsfall (muco)protein, derived from the proximal renal tubule). Protein excretion can rise transiently with fever, acute illness, urinary tract infection (UTI) and orthostatically. In pregnancy, the upper limit of normal protein excretion is around 300 mg/day. Persistent elevation of albumin excretion (microalbuminuria) and other proteins can indicate renal or systemic illness.

- Repeat positive dipstick tests for blood and protein in the urine two or three times to ensure the findings are persistent.

- Microalbuminuria is an early sign of renal and cardiovascular dysfunction with adverse prognostic significance.

- Non-visible haematuria (NVH) is present in around 4% of the adult population—of whom at least 50% have glomerular disease.

- If initial glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is normal, and proteinuria is absent, progressive loss of GFR amongst those people with NVH of renal origin is rare, although long-term (and usually community-based) follow-up is still recommended.

- Adults aged 40 years old or more should undergo cystoscopy if they have NVH.

- Any patient with NVH who has abnormal renal function, proteinuria, hypertension and a normal cystoscopy should be referred to a nephrologist.

- Blood pressure control, reduction of proteinuria and cholesterol reduction are all useful therapeutic manoeuvres in those with renal causes of NVH.

- All NVH patients should have long-term follow-up of their renal function and blood pressure (this can, and often should be, community-based).

- Renal function is measured using creatinine, and this is now routinely converted into an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) value quickly and easily.

- The most common imaging technique now used for the kidney is the renal ultrasound, which can detect size, shape, symmetry of kidneys and presence of tumour, stone or renal obstruction.

Symptoms of chronic kidney disease (CKD) are often non-specific (Table 1.1). Clinical signs (of CKD, or of systemic diseases or syndromes) may be present and recognized early on in the natural history of kidney disease but, more often, both symptoms and signs are only present and recognized very late—sometimes too late to permit effective treatment in time to prepare for dialysis. However, the most commonly performed test of renal function—plasma creatinine—is typically performed with every hospital inpatient and as part of investigations or screening during many GP surgery or hospital clinic outpatient episodes.

Table 1.1 Signs and symptoms of chronic kidney disease

| Symptoms | Signs |

| Tiredness | Pallor |

| Anorexia | Leuconychia |

| Nausea and vomiting | Peripheral oedema |

| Itching | Pleural effusion |

| Nocturia, frequency, oliguria | Pulmonary oedema |

| Haematuria | Raised blood pressure |

| Frothy urine | |

| Loin pain |

Unlike ‘angina’ or ‘chronic obstructive airways disease’, where a history can be revealing (e.g. walking distance or cough), there is little that is quantifiable about CKD severity without blood and/or urine testing.

This is why serendipitous discovery of kidney problems (haematuria, proteinuria, structural abnormalities on kidney imaging or loss of kidney function) is a common ‘presentation’. A full understanding of what these abnormalities mean and a clear guide to ‘what to do next’ are particularly needed in kidney medicine, and filling this gap is one of the aims of this book.

Correct use and interpretation of urine dipsticks and plasma creatinine values (by far the commonest tests used for screening and identification of kidney disease) is the main focus of this chapter. Renal imaging and renal biopsy will also be described briefly.

Urine Testing

Urinalysis is a basic test for the presence and severity of kidney disease. Testing urine during the menstrual period in women, and within 2–3 days of heavy strenuous exercise in both genders, should be avoided, to avoid contamination or artefacts. Fresh ‘mid-stream’ urine is best, again to reduce accidental contamination. Refrigeration of urine at temperatures from +2 to +8°C assists preservation. Specimens that have languished in an overstretched hospital laboratory specimen reception area, before eventually undergoing analysis, will rarely reveal all of the potential information that could have been gained.

Changes in urine colour are usually noticed by patients. Table 1.2 shows the main causes of different-coloured urine. Chemical parameters of the urine that can be detected using dipsticks include urine pH, haemoglobin, glucose, protein, leucocyte esterase, nitrites and ketones. Figure 1.1 shows the dipstick in its ‘dry’ state and an example of a positive test. Table 1.3 shows the main false negative and false positive results that can interfere with correct interpretation.

Table 1.2 The main causes of differently coloured urine

| Pink–red–brown–black | Yellow–brown | Blue–green |

| Gross haematuria (e.g. bladder or renal tumour; IgA nephropathy) | Jaundice Drugs: chloroquine, nitrofurantoin | Drugs: triamterene |

| Dyes: methylene blue | ||

| Haemoglobinuria (e.g. drug reaction) | ||

| Myoglobinuria (e.g. rhabdomyolysis) | ||

| Acute intermittent porphyria | ||

| Alkaptonuria | ||

| Drugs: phenytoin, rifampicin (red); metronidazole, methyldopa (darkening on standing) | ||

| Foods: beetroot, blackberries |

Figure 1.1 Urine dipstick—the urine on the right is normal and the colours of all of the squares on the urine dipstick are normal/negative. The urine on the left is from someone with acute glomerulonephritis, looks pink-brown macroscopically and has maximal blood and protein on the dipstick.

Table 1.3 The main causes of false negative and false positive testing from use of urine dipsticks

| Test | False positive | False negative |

| Haemoglobin | Myoglobin | Ascorbic acid |

| Microbial peroxidases | Delayed examination | |

| Proteinuria | Very alkaline urine (pH 9) | Tubular proteins |

| Chlorhexidine | Immunoglobulin light chains | |

| Globulins | ||

| Glucose | Oxidizing detergents | UTI |

| Ascorbic acid |

Discounting contamination from menstrual—or other—bleeding, and exercise-induced haematuria and proteinuria.

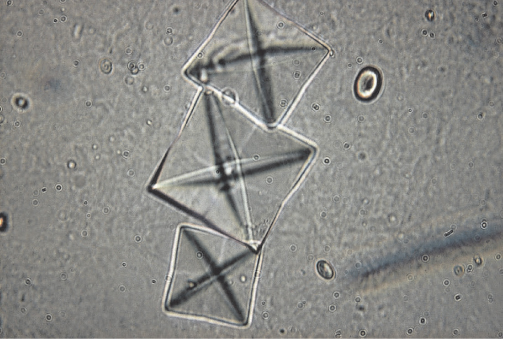

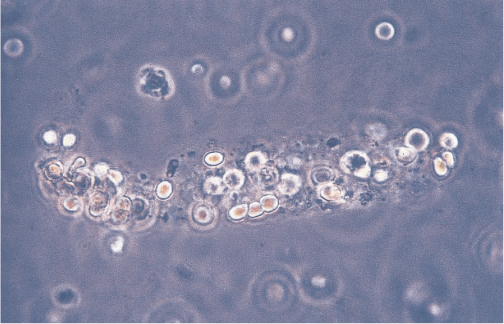

Urine microscopy can only add useful information to urinalysis when there is a reliable methodology for collection, storage and analysis. This is often lacking, even in hospitals. Early-morning urine is best, with rapid sample centrifugation. Under ideal circumstances cells (erythrocytes, leucocytes, renal tubular cells and urinary epithelial cells), casts (cylinders of proteinaceous matrix), crystals, lipids and organisms can be reliably identified where present in urine. Figure 1.2 shows a red cell cast in urine (indicative of acute renal inflammation). Figure 1.3 shows urinary crystals.

Figure 1.2 Microscopy of centrifuged fresh urine. There is a red cell cast (protein skeleton with incorporated red blood cells). This is characteristic of acute glomerulonephritis.

Non-visible Haematuria

Definition and Background

In healthy people red blood cells (rbc) are not present in the urine in > 95% of cases. Large numbers of rbcs make the urine pink or red.

Non-visible haematuria (NVH) (formerly known as microscopic haematuria) is commonly defined as the presence of greater than two rbcs per high power field in a centrifuged urine sediment. It is seen in 3–6% of the normal population, and in 5–10% of those relatives of kidney patients who undergo screening for potential kidney donation.

NVH can be an incidental finding of no prognostic importance, or the first sign of intrinsic renal disease or urological malignancy. It always requires assessment, and most often requires referral to a kidney specialist or to a urologist.

Clinical Features

The finding of NVH is usually as a result of routine medical examination for employment, insurance or GP-registration purposes in an otherwise apparently healthy adult. Initially, therefore, NVH is an issue for primary healthcare workers. The goal of an assessment is to understand whether:

- there are any clues available from the patient’s history, his/her family history or from examination to point to a particular diagnosis, e.g. connective tissue disease, sickle cell disease;

- the haematuria is transient or persistent;

- there is any evidence of renal disease, e.g. abnormal renal function, accompanying proteinuria, raised blood pressure (BP);

- the haematuria represents glomerular (i.e. from the kidney) or extra-glomerular (urological) bleeding.

Investigations

Typically, the full evaluation of NVH requires hospital-based investigations. Box 1.1 lists these in a logical order.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree