Fig. 14.1

End-to-side jejunoileal bypass. Reprinted with permission from Chousleb E, Rodriguez JA, O’Leary JP. Chapter 3. History of the Development of Metabolic/Bariatric Surgery. In: Nguyen NT, Rosenthal R, Ponce J, Morton J, Blackstone R (eds). The ASMBS Textbook of Bariatric Surgery, Vol. 1. New York, NY: Springer. 2014

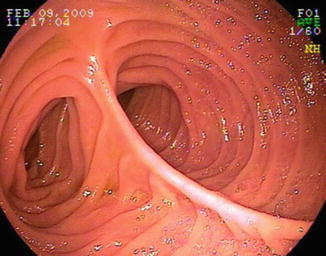

Fig. 14.2

Endoscopic view of an end-to-side anastomosis. Notice there are two stomal lumens

Fig. 14.3

Small bowel side-to-side anastomosis. Reprinted with permission from Chousleb E, Rodriguez JA, O’Leary JP. Chapter 3. History of the Development of Metabolic/Bariatric Surgery. In: Nguyen NT, Rosenthal R, Ponce J, Morton J, Blackstone R (eds). The ASMBS Textbook of Bariatric Surgery, Vol. 1. New York, NY: Springer. 2014

From an endoscopic view, it can be challenging to determine between the lumens of the anastomosed limbs. Usually the presence of a scar can aid with distinguishing between them. The efferent limb (limb used to reach the anastomosis) will have an intact mucosa on the contralateral portion of the small bowel wall to the anastomosis. This is different from the afferent limb, which would have a circumferential scar around the opening of the stoma. Therefore as a rule, to intubate the afferent limb, the anastomosis scar rim must be trespassed [2]. Careful observation of the peristaltic wave can also be useful to differentiate between limbs. The efferent limb will have a peristalsis wave that will move away from the endoscope (natural downstream peristalsis), but the afferent limb will have a peristaltic wave that would move toward the endoscope, which is also known as antiperistalsis (Video 14.3). In spite of these distinctions, the limbs are not always distinguishable, and in these cases the endoscopist will have to rely on fluoroscopic guidance to confirm the direction toward the desired quadrant (e.g., right upper quadrant if in need to reach the papilla on a Billroth II patient), or they will need to advance the scope as far as possible. If this latter strategy is followed, then we recommend marking the mucosa (e.g., biopsy or tattoo) of the limb to be examined. This might save time later upon withdrawal of the scope back to the anastomosis, as the scope can commonly fall back briskly upon withdrawal due to bowel fixation and angulation at the level of the anastomosis. If the limbs’ openings are not clearly distinguishable (e.g., biopsy or tattoo), it can be difficult to determine which was the limb recently examined.

Billroth I

In Billroth I, the distal stomach is resected and the remaining stomach is anastomosed to the duodenum (Fig. 14.4) [1]. The endoscopist will encounter an intact esophagus and GEJ. The length of the stomach would vary depending on the extent of gastric resection. The endoscopist will find the anastomosis by following the greater curvature of the stomach. The bulb might be small or not present at all, and the duodenum will typically appear straightened [1].

Fig. 14.4

Billroth I anastomosis diagram. Reprinted with permission Feitoza AB, Baron TH. Endoscopy and ERCP in the setting of previous upper GI tract surgery. Part II: postsurgical anatomy with alteration of the pancreaticobiliary tree. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. Jan 2002;55(1):75–79

Billroth II

In Billroth II, the distal stomach and first portion of the duodenum are resected. Different to a Billroth I, the duodenal stump is closed and instead the stomach is anastomosed to the jejunum in an end-to-side fashion, creating a gastrojejunostomy with two stomas—one each leading to the efferent and afferent limbs (Fig. 14.5 [1], Video 14.4). To reach the major papilla, the afferent limb should be intubated. The afferent limb will end as a blind stump. The presence of bile and fluoroscopic confirmation of the direction of the scope toward the right upper quadrant or to cholecystectomy clips can help confirm the scope is within the afferent limb.

Fig. 14.5

Billroth II anastomosis diagram. Reprinted with permission Feitoza AB, Baron TH. Endoscopy and ERCP in the setting of previous upper GI tract surgery. Part II: postsurgical anatomy with alteration of the pancreaticobiliary tree. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. Jan 2002;55(1):75–79

Braun Anastomosis

This is a side-to-side jejunojejunal anastomosis commonly seen during Billroth II reconstruction to divert bile from the gastric remnant by creating an anastomosis between both the efferent and afferent limbs (Fig. 14.6) [1].This means that the endoscopist would encounter a side-to-side anastomosis after intubating either opening of the gastrojejunal anastomosis. This Braun anastomosis is approximately 15 cm from the gastrojejunal anastomosis [1].

Fig. 14.6

Braun anastomosis diagram. Reprinted with permission Feitoza AB, Baron TH. Endoscopy and ERCP in the setting of previous upper GI tract surgery. Part II: postsurgical anatomy with alteration of the pancreaticobiliary tree. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. Jan 2002;55(1):75–79

Roux-en-Y Gastrojejunal Bypass

Roux-en-Y gastrojejunal bypass (RYGB) can be performed with gastrectomy (e.g., gastric cancer) or without gastrectomy (e.g., gastric bypass for weight loss) (Fig. 14.7). With either gastric bypass or partial distal gastrectomies, the endoscopist will encounter a normal esophagus and normal gastroesophageal junction. The gastric pouch will be connected distally to the jejunum in an end-to-side anastomosis. If the RYGB was performed for weight loss, the gastric pouch would be significantly smaller and will have a suture line or scar laterally [3]. This gastrojejunal anastomosis can have a length of 10–12 cm and will commonly have two small bowel limbs: a short blind limb and the efferent or Roux jejunal limb (Video 14.5) [3]. The length of the Roux limb can vary between 50 and 150 cm, with longer limbs used for weight loss surgeries and shorter ones for gastrectomy patients [3]. At the end of the Roux limb, the endoscopists will find a jejunojejunal anastomosis. If the Roux-en-Y was performed for gastric bypass, the afferent limb will lead to the papilla and the stomach remnant can be entered in a retrograde fashion through an intact pylorus (Video 14.5). In a gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y, the limb will end in a blind stump similar to that seen on Billroth II anastomosis.

Fig. 14.7

Roux-en-Y limb for gastrojejunostomy. Reprinted with permission from Chousleb E, Rodriguez JA, O’Leary JP. Chapter 3. History of the Development of Metabolic/Bariatric Surgery. In: Nguyen NT, Rosenthal R, Ponce J, Morton J, Blackstone R (eds). The ASMBS Textbook of Bariatric Surgery, Vol. 1. New York, NY: Springer. 2014

Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch

A biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch consists of a partial gastrectomy (vertical sleeve gastrectomy) with preservation of the distal antrum, pylorus, and duodenal bulb; transection of the small bowel approximately half way between the ligament of Treitz and the ileocecal valve; and two enteroentero anastomoses—one between the duodenal bulb and the limb attached to the ileocecal valve (also known as the alimentary limb) and the second between the limb attached to the papilla (also known as the biliopancreatic limb) and the alimentary limb (Fig. 14.8) [4].

Fig. 14.8

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch diagram. From Decker GA, Swain JM, Crowell MD, Scolapio JS. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2571–80. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, all rights reserved

The endoscopist will encounter a normal esophagus and GEJ and then will find a stomach with a vertical sleeve gastrectomy. This means the lesser curvature will be intact and there will be a long vertical scar on the contralateral wall. The stomach would have a tubular shape but will have a preserved pylorus. Once the pylorus is transverse, the endoscopist will encounter the duodenal bulb and, soon after, an anastomosis with the alimentary limb. If the endoscopist continues down the alimentary limb, the endoscopist will reach a second enteroentero anastomosis. This anastomosis will have two open stomas: one into the biliopancreatic limb and the other into the common channel. Distal to the anastomosis into the common channel limb, the endoscopist will reach the ileocecal valve. If the papilla needs to be reached, the biliopancreatic limb will have to be intubated. This limb is considerably longer when compared to Roux-en-Y gastrojejunal bypass.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree