Grade

Injury description

I

Hematoma

Subcapsular, <10 % surface area

Laceration

Capsular tear, <1 cm parenchymal depth

II

Hematoma

Subcapsular, 10–50 % surface area; intraparenchymal, <10 cm diameter

Laceration

1–3 cm parenchymal depth, <10 cm length

III

Hematoma

Subcapsular, >50 % surface area or expanding. Ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal hematoma; intraparenchymal hematoma >10 cm or expanding

Laceration

>3 cm parenchymal depth

IV

Laceration

Parenchymal disruption involving 25–75 % of hepatic lobe or >3 Couinaud’s segments within a single lobe

V

Laceration

Parenchymal disruption involving >75 % of hepatic lobe or 1–3 Couinaud’s segments within a single lobe

Vascular

Juxtahepatic venous injuries, i.e., retrohepatic vena cava/central major hepatic veins

VI

Vascular

Hepatic avulsion

Eighty-five percent of patients had AAST-OIS liver injuries grades I, II, and III and 15 % had injuries grades IV, V, and VI. The author created a new classification that can be performed intraoperatively and permits the surgeon to take rapid and concise treatment options accordingly:

Grade I: The bleeding is minor and can be controlled by temporary liver packing, topical hemostatic agents, and/or hepatorrhaphy.

Grade II: Moderate liver bleeding that requires a Pringle maneuver and perihepatic liver packing that is left in as part of a damage control approach.

Grade III: Liver bleeding that cannot be controlled with a Pringle maneuver and perihepatic packing or rebleeds once the Pringle is released. The source of bleeding is probably secondary to hepatic veins or retrohepatic vena caval injury. Additional advance surgical maneuvers are required for hemorrhage control [2].

Surgical Approach

The initial surgical approach to any penetrating abdominal trauma victim who arrives in severe hypovolemic shock is to perform an immediate exploratory laparotomy that permits a full exposure of the abdominal cavity and/or retroperitoneum. We recommend a stepwise approach:

Step 1: The hemoperitoneum must be collected, quantified, and autotransfused when possible. All four quadrants of the abdominal cavity should then be packed with special attention directed toward adequately packing the liver. We do not recommend using initially any plastic protective barrier between the liver and the packs because it is our experience that this interferes with the adequate placement of the packs. Following the initial perihepatic packing, we recommend a Pringle maneuver which can remain in place in most non-cirrhotic patients for up to 60 min and up to 15 min in those who are cirrhotic. The porta hepatis cross clamping can be repeated with reperfusion intervals of 5 min [3–7] (Fig. 13.1). Immediate bowel contamination is controlled by quickly stapling or tying off any injured segments of small or large bowel.

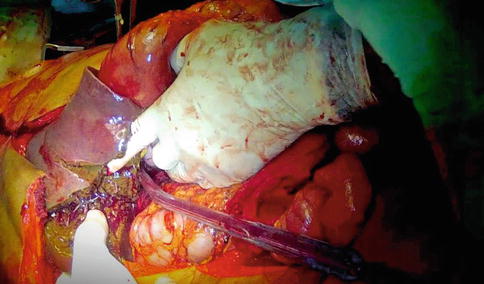

Fig. 13.1

Pringle maneuver

Step 2: A complete quick systematic evaluation of all infra- and supra-mesocolic organs of the abdominal cavity is performed to determine the amount and extent of all associated injuries. At this point, an early determination must be made to determine the need to establish damage control resuscitation (DCR). For this purpose, we follow an explicit set of parameters that we have simplified in an easily remembered ABCD mnemonic. The presence of all four of the following components is necessary:

A = acidosis (base deficit > −8)

B = blood loss (hemoperitoneum > 1,500 mL)

C = cold (temperature < 35 C)

D = damage (New ISS [NISS] > 35)

At the same time, concepts of damage control surgery are simultaneously performed such as abdominal packing, aortic cross clamping, shunt placements for vascular trauma, and fecal contamination control [5].

Step 3: After having evacuated the hemoperitoneum and controlled all possible fecal contamination sources, we proceed on grading the liver injury. We use a modified penetrating liver injury scale devised by Ferrada et al., which is based on a vast experience over many years of an unfortunate Colombian drug-funded civil war:

Grade I: Upon removal of perihepatic packing, liver bleeding has stopped or requires simple techniques of hemostasis such as topical hemostatic agents and/or hepatorrhaphy and the procedure is truncated.

Grade II: The bleeding is controlled by combining a Pringle maneuver and perihepatic packing. The initial immediate liver packing upon laparotomy is removed, the extent of the liver injury is determined, a Pringle maneuver is placed resulting in a significant decrease in the bleeding, and then a definitive 8–10 packs are placed perihepatically. The definitive packing should be done as quickly as possible before the patient becomes coagulopathic. A prime principle of perihepatic packing is that the vectors of compression created by the selective placement of the packs should result in an adequate compressive opposition of the fractured liver borders. To obtain this kind of packing, the liver needs to be completely mobilized and compressed manually by an assistant while the surgeon places the perihepatic packs. This usually requires two to four packs on each vector plane of compression. If there is a large deep laceration, then placement of intraparenchymal hemostatic agents should be done first, followed by gauze packing in a folded accordion fashion. We have learned that there are several technical mishaps regarding liver packing. The first is the issue of overpacking which can result in intra-abdominal hypertension with an associated decrease in cardiac preload and subsequent hemodynamic instability due to the decrease blood return from the compressed retrohepatic vena cava. Another common error is the other extreme of too few packs placed which results in an inefficacious compression of the liver injury and subsequent persistent bleeding. The initial damage control surgery should not be terminated until all ongoing surgical bleeding from the liver has been controlled. This can be verified by assuring that the most superficial packs remain dry and white. If this is not the case, then the packs should be removed and the liver injury reevaluated. In the case that the packs are dry, the Pringle maneuver is removed, and the condition of the packs is re-examined, if dry, then the surgery can be truncated. All of this should be done in the least time possible to avoid that the patient develops the triad of death: hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis. The abdomen is washed out, temporary abdominal closure coverage is placed, and the patient is taken immediately to the intensive care unit to continue his damage control resuscitation.

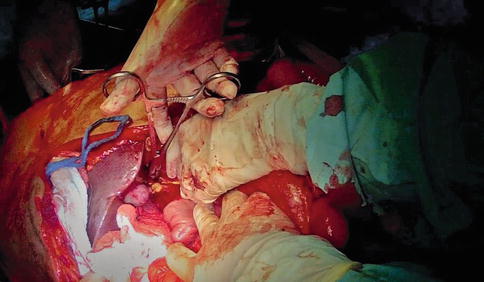

Step 4: Some trauma surgeons advocate the complete mobilization of the liver at the time of the take back of the patient to visualize the injury and remove the packs (Fig. 13.2). We believe that if required, the mobilization of the liver should be done during the initial laparotomy and that performing it at any other time just increases the chances of rebleeding of an injury that had already subsided.