Cystitis

INFECTIOUS

Encrusted Cystitis

Encrusted cystitis refers to inorganic salts being deposited on an injured urothelial mucosa as a consequence of urea-splitting bacteria, alkalinizing urine (1). This lesion is most common in women. Histologically, deposits of calcium are present in the lamina propria, and the mucosal surface of the bladder is covered with fibrin mixed with calcific, necrotic debris associated with inflammatory cells.

Emphysematous Cystitis

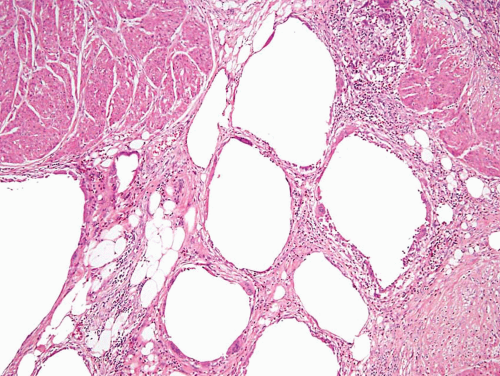

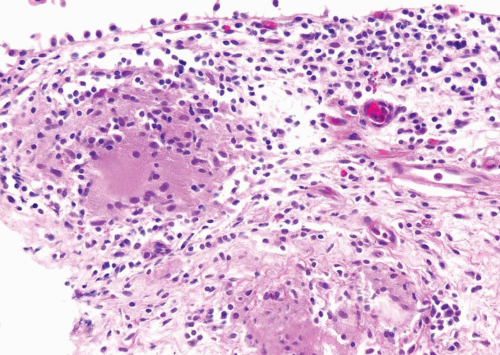

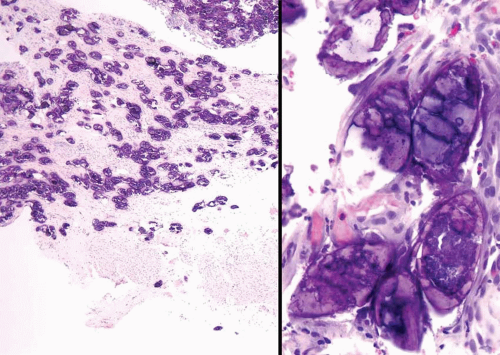

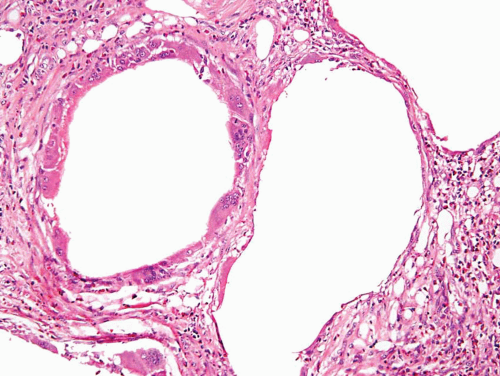

This lesion, also known as pneumatosis of the bladder, refers to the presence of gas-filled blebs, predominantly within the lamina propria, which can be seen both at cystoscopy and on a gross examination (2). This lesion is more typically found in women, often diabetic, and associated with bacterial infections. Predisposing conditions include trauma, fistula, instrumentation, and urinary stasis. Microscopically, the blebs consist of empty cavities lined by flattened cells surrounded by thin septa; frequently there is an associated foreign body giant cell reaction focally lining the empty spaces (Figs. 10.1, 10.2).

Fungal Cystitis

Fungal cystitis is uncommon and most often caused by Candida albicans (3). Cases of cystitis caused by Aspergillus species and other fungi have also been rarely reported. Women are predominantly affected. Most patients are debilitated or are on an antibiotic therapy, with diabetic patients being another commonly affected group.

Tuberculosis (Including Bacillus Calmette-Guérin)

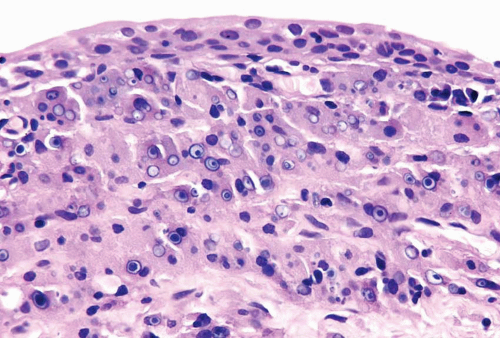

Most bladder lesions involving Mycobacterium tuberculosis are secondary to renal involvement (4). Typically, the infection begins around ureteral orifices with superficial ulceration, with acute and chronic inflammation and initially noncaseating granulomas. Larger caseating granulomas may follow. Late complications include ulcers with fibrosis that can result in ureteral strictures. The histology of tuberculosis more typically seen in current

practice is that associated with intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy for superficial bladder cancer and consists of small, noncaseating granulomas (Fig. 10.3) (see “Treatment Related”). In patients with a known history of BCG immunotherapy and granulomas on bladder biopsy, we do not perform special stains for organisms.

practice is that associated with intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy for superficial bladder cancer and consists of small, noncaseating granulomas (Fig. 10.3) (see “Treatment Related”). In patients with a known history of BCG immunotherapy and granulomas on bladder biopsy, we do not perform special stains for organisms.

Schistosomiasis

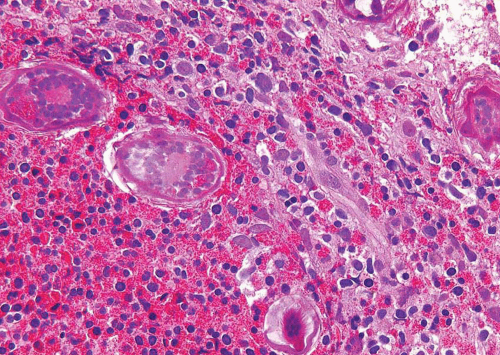

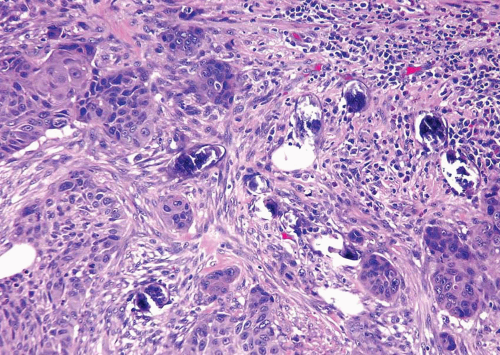

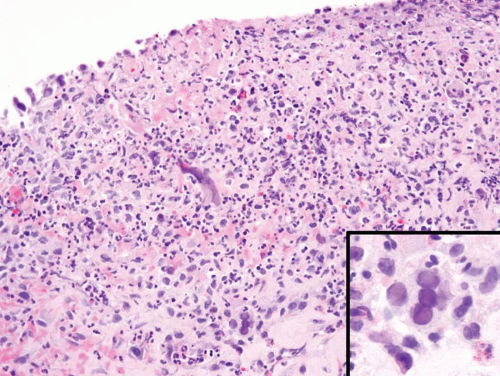

Schistosomiasis is a chronic disease involving the bladder, caused by larvae of Schistosoma haematobium (5, 6) (Figs. 10.4, 10.5 and 10.6) (efigs 10.1-10.5).

Coupled adult male and female worms migrate to the veins of the vesical and pelvic plexuses, where they mate and females begin to lay eggs. Involvement of various urogenital organs correlates with the extent of the venous circulation, such that the urinary bladder with a rich venous supply is most heavily infected. Schistosomiasis most commonly occurs in the Middle East and in most of the African continent. The highest incidence is where irrigation agriculture is prevalent, such as in the Nile Valley and Delta. The initial response to S. haematobium infection is a reaction of the host against the deposition of eggs. This lesion manifests as a granulomatous reaction to the eggs surrounded by numerous eosinophils. S. haematobium eggs have terminal spines that differentiate them from

other schistosomes, but this is difficult to appreciate in histologic sections. Another differentiating feature is that S. haematobium eggshells are not acid-fast, whereas Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum eggs are. There are several histologic stages of schistosomiasis within the bladder. Recent oviposition gives rise to perioval granulomatous inflammation, which can result in hyperemic polypoid masses. With greater chronicity and lower ova position, eggs are destroyed or calcified, and inflammation subsides. This gives rise to more fibrous tissue and “sandy patches,” in which there is atrophy of the surface epithelium over the schistosomal lesion; old calcified schistosomal eggs buried immediately beneath the mucosa resemble sand seen through shallow water. One may also see

schistosomal tubercles that are a manifestation of early active disease, appearing as seed-like, yellowish specks just beneath the urothelium. Each speck reflects a granuloma surrounded by a circle of hyperemia.

Coupled adult male and female worms migrate to the veins of the vesical and pelvic plexuses, where they mate and females begin to lay eggs. Involvement of various urogenital organs correlates with the extent of the venous circulation, such that the urinary bladder with a rich venous supply is most heavily infected. Schistosomiasis most commonly occurs in the Middle East and in most of the African continent. The highest incidence is where irrigation agriculture is prevalent, such as in the Nile Valley and Delta. The initial response to S. haematobium infection is a reaction of the host against the deposition of eggs. This lesion manifests as a granulomatous reaction to the eggs surrounded by numerous eosinophils. S. haematobium eggs have terminal spines that differentiate them from

other schistosomes, but this is difficult to appreciate in histologic sections. Another differentiating feature is that S. haematobium eggshells are not acid-fast, whereas Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum eggs are. There are several histologic stages of schistosomiasis within the bladder. Recent oviposition gives rise to perioval granulomatous inflammation, which can result in hyperemic polypoid masses. With greater chronicity and lower ova position, eggs are destroyed or calcified, and inflammation subsides. This gives rise to more fibrous tissue and “sandy patches,” in which there is atrophy of the surface epithelium over the schistosomal lesion; old calcified schistosomal eggs buried immediately beneath the mucosa resemble sand seen through shallow water. One may also see

schistosomal tubercles that are a manifestation of early active disease, appearing as seed-like, yellowish specks just beneath the urothelium. Each speck reflects a granuloma surrounded by a circle of hyperemia.

FIGURE 10.2 Higher magnification of Figure 10.1 showing empty spaces of air surrounded by giant cell reaction. |

Patients with schistosomiasis of the lower urinary tract typically present with painful micturition, frequent urination, pyuria, and hematuria. Anemia and eosinophilia are common. With greater chronicity, individuals acquire “contracted bladder” syndrome, in which there is an intense ova position involving all levels of muscularis propria with dense fibrosis. Patients present with intractable frequency, painful urination, urgency, and incontinence. Surgery may be indicated when the bladder capacity is significantly reduced, requiring augmentation cystoplasty, using either ileum or colon. Another complication of schistosomiasis within the bladder is ulceration that is attributed to local ischemia caused by schistosomal obliteration of deeper vessels or onset of secondary bacterial infection. Although ulcers may respond to antischistosomal therapy, often total excision by partial cystectomy or endoscopic resection is required. Other nonneoplastic complications include bladder neck obstruction and ureteral strictures. Males are affected more than females in a 4:1 ratio. Carcinogenesis resulting from schistosomal infections is the result of chronic injury, often accompanying bacterial infection, foreign bodies, and urinary concentration of nitrosamines (see Chapter 9).

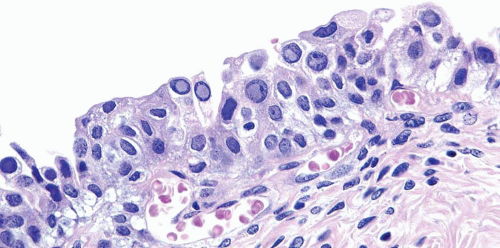

Malakoplakia

Malakoplakia may affect multiple organs, although the bladder is the most commonly involved (7). The lesion is characterized by large histiocytes, known as von Hansemann cells, and small basophilic extracytoplasmic or intracytoplasmic calculopherules, called Michaelis-Gutmann bodies (Fig. 10.7) (efigs 10.6-10.11). The bodies are found within the interstitium as well as within the histiocytes. Bacteria or bacterial fragments form a nidus

for the calcium phosphate crystals that laminate the Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. A defect in the intraphagosomal digestion, which accounts for the unusual immune response, gives rise to malakoplakia (8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). Electron microscopy reveals intact coliform bacteria and bacterial fragments within phagolysosomes within the foamy histiocytes. The overlying urothelium may be ulcerated, hyperplastic, or metaplastic. In long-standing lesions, the characteristic infiltrate is replaced by fibrosis and scarring. Most patients are middle-aged, with a female predominance of 4:1. Patients may be debilitated, immunosuppressed, or have other chronic diseases. Cystoscopy reveals mucosal plaques and nodules that occasionally become larger masses. There can be significant morbidity, including ureteral strictural stenosis, giving rise to renal obstruction or nonfunction. Management of malakoplakia is primarily based on controlling the urinary tract infections, which stabilizes the disease. Adding bethanechol, a cholinergic agent thought to increase the intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels considered to be the defect-causing macrophage dysfunction, may also be useful. Surgery may be necessary as the disease progresses, despite antimicrobial treatment. Malakoplakia may also result in death if it involves both kidneys. Iron and calcium stains can highlight Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, although they are usually quite evident on routine hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections.

for the calcium phosphate crystals that laminate the Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. A defect in the intraphagosomal digestion, which accounts for the unusual immune response, gives rise to malakoplakia (8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). Electron microscopy reveals intact coliform bacteria and bacterial fragments within phagolysosomes within the foamy histiocytes. The overlying urothelium may be ulcerated, hyperplastic, or metaplastic. In long-standing lesions, the characteristic infiltrate is replaced by fibrosis and scarring. Most patients are middle-aged, with a female predominance of 4:1. Patients may be debilitated, immunosuppressed, or have other chronic diseases. Cystoscopy reveals mucosal plaques and nodules that occasionally become larger masses. There can be significant morbidity, including ureteral strictural stenosis, giving rise to renal obstruction or nonfunction. Management of malakoplakia is primarily based on controlling the urinary tract infections, which stabilizes the disease. Adding bethanechol, a cholinergic agent thought to increase the intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels considered to be the defect-causing macrophage dysfunction, may also be useful. Surgery may be necessary as the disease progresses, despite antimicrobial treatment. Malakoplakia may also result in death if it involves both kidneys. Iron and calcium stains can highlight Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, although they are usually quite evident on routine hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections.

Viral Cystitis

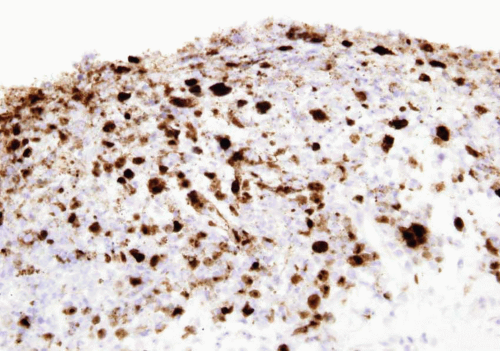

Both adenovirus and herpes simplex type 2 virus have been associated with hemorrhagic cystitis in a few patients (Figs. 10.8, 10.9) (14, 15). Herpes zoster and cytomegalovirus have also been rarely implicated in bladder infections (16, 17).

FIGURE 10.9 Immunohistochemistry for herpes virus demonstrates more virus than appreciable on H&E stained section (same case seen in Figure 10.8). |

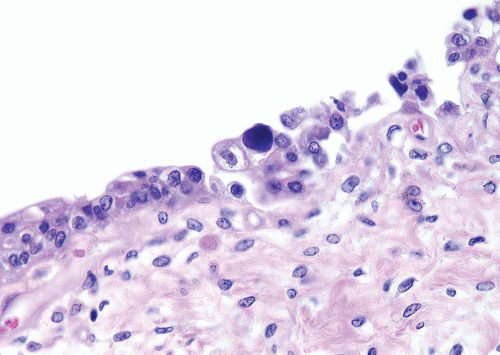

Patients with polyoma viruses and bladder involvement are usually immunosuppressed renal or bone marrow allograft recipients with hemorrhagic cystitis (18, 19). Despite the frequency of viruria and intranuclear inclusions seen in urinary cytology specimens in these patients, the identification of inclusions in histologic tissue sections is rare (20) (Figs. 10.10, 10.11) (efigs 10.12-10.13). The cytohistologic discordance might be due to the following reasons: (a) polyoma (BK) virus-infected cells are shed from the tissue and collected in the urine; (b) polyoma virus changes may be focal and not sampled in directed tissue biopsies; and (c) polyoma virus changes may originate from sites in the genitourinary tract other than the bladder.

NONINFECTIOUS

Polypoid Cystitis

Polypoid cystitis may arise as a reaction to any inflammatory insult to the urinary mucosa (21, 22, 23) (efigs 10.14-10.46). The presence of indwelling catheters is a well-recognized etiology for polypoid cystitis.

However, any factor that irritates the bladder mucosa can result in polypoid cystitis, such as colovesical fistulas, calculi, urinary tract obstruction, and prior radiation therapy. It occurs equally in males and females, with an age range of 20 months to 79 years. Cystoscopically, it appears either as an area of friable mucosal irregularity or edematous broad papillae. Lesions may be multifocal and can range up to 5 mm in size.

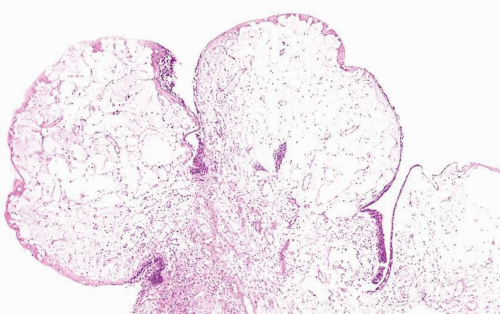

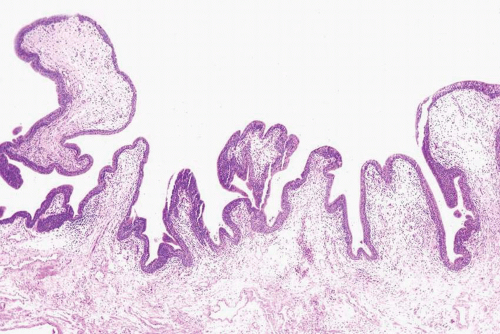

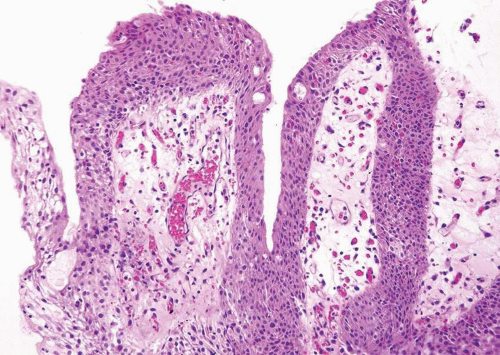

In its most pronounced form, polypoid cystitis shows extensive submucosal edema with broad bulbous projections termed as bullous cystitis (Fig. 10.12). Other cases of polypoid cystitis may be more difficult to distinguish from papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential and papillary carcinoma. However, these examples of polypoid cystitis still show edematous fibrovascular cores that are broad based in contrast to narrow-necked, thin, and delicate fibrovascular cores of papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential and papillary urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 10.13). The fronds in polypoid cystitis do not branch into smaller papillae as can be seen in papillary urothelial carcinoma. While these are the classic features of polypoid cystitis, in a minority of cases there may be narrow-based fronds, typically associated with broad-based fronds elsewhere in the lesion but occasionally as the sole finding (Fig. 10.14) (Table 10.1) (21). Other overlapping features can also lead to a misdiagnosis. Isolated papillary fronds within the otherwise classic polypoid cystitis may lack edema, and out of context can closely resemble a papillary neoplasm. Conversely, occasional fronds of papillary urothelial neoplasia may be edematous and have some inflammation. Similarly, in a minority of polypoid cystitis cases, the urothelium may be focally or even diffusely thickened although not typically to the extent seen in some papillary urothelial neoplasms.

TABLE 10.1 Histology of Polypoid Cystitis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With time, fronds of polypoid cystitis lesions become less edematous and are replaced by dense fibrosis often associated with chronic inflammation. These lesions may be referred to as papillary cystitis (21) (Figs. 10.15, 10.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree