Dyspepsia is a highly prevalent condition characterized by symptoms originating in the gastroduodenal region without underlying organic disorder. Treatment modalities include acid-suppressive drugs, gastroprokinetic drugs, Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, tricyclic antidepressants, and psychological therapies. Irritable bowel syndrome is a multifactorial, lower functional gastrointestinal disorder involving disturbances of the brain-gut axis. The pathophysiology provides the basis for pharmacotherapy: abnormal gastrointestinal motor functions, visceral hypersensitivity, psychosocial factors, intraluminal changes, and mucosal immune activation. Medications targeting chronic constipation or diarrhea may also relieve irritable bowel syndrome. Novel approaches to treatment require approval, and promising agents are guanylate cyclase cagonists, atypical benzodiazepines, antibiotics, immune modulators, and probiotics.

Functional dyspepsia (FD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are two of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders. Dyspepsia is increasingly recognized as related to ingestion of food; it is currently considered to consist of two main conditions: epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) and postprandial distress syndrome (PDS), the latter characterized by early satiation and postprandial fullness/discomfort. In addition, symptoms of nausea (and rarely vomiting), bloating, and belching may also be present. A subset of patients with FD may also lose weight. Among tertiary referral patients with FD, approximately 30% of patients have delayed gastric emptying, 10% have accelerated gastric emptying, 40% have impaired gastric accommodation after meals, and 30% have evidence of hypersensitivity to gastric distention. Alternatively, among community FD patients, there is little evidence of abnormal gastric sensory or motor physiology, and the predominant associated factor is psychosocial disturbance. In tertiary care dyspeptics, psychosocial disturbance was also identified as the major factor underlying symptom severity.

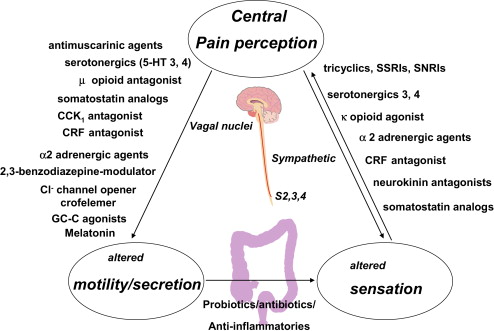

IBS is characterized by abdominal pain and discomfort in association with altered bowel habits; symptoms are not explained by structural abnormalities using current standard diagnostic tests. The pathophysiology of IBS is still not well understood but is most likely multifactorial. Several factors, such as motor and sensory dysfunction, neuroimmune mechanisms, psychological factors, and changes in the intraluminal milieu seem to play a role ( Fig. 1 ). Recent imaging-based studies using radiopaque markers or scintigraphy show that approximately 20% of patients with constipation predominant (IBS-C) and 45% of patients with diarrhea predominant (IBS-D), respectively, have retardation or acceleration of colonic transit. The increased release of serotonin in the circulation, especially in the IBS-D group, and increased serine proteases (derived from mast cells) in the stool of patients with IBS provide evidence for the potential role of neurotransmitters or chemical mediators such as proteases in the disorder.

Changes in mucosal serotonin or mucosal dysfunction, immune activation, or inflammation may contribute to IBS symptoms and, possibly, alterations in colonic bacterial flora. An increased number of activated mast cells in the proximity of colonic nerves in the lamina propria is associated with abdominal pain severity. Mucosal immune activation is associated with systemic evidence for a proinflammatory state (decreased IL-10/IL-12 ratio) in IBS patients and changes in local defense mechanisms in the sigmoid and colonic mucosa in IBS. These provide novel promising targets for future therapies. Studies of colonic mucosal function in vitro suggest there is a barrier function in IBS patients; in vivo measurements have not provided a uniform message.

Traditional IBS therapies (see Fig. 1 ) are mainly directed at relief of individual symptoms (eg, antidiarrheals for diarrhea, laxatives for constipation, or smooth muscle relaxants for pain). They are often of limited efficacy in addressing the overall symptom complex.

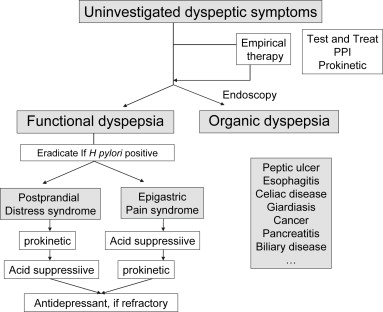

This article reviews the current management of dyspepsia and IBS therapy ( Box 1 , Fig. 2 ); pharmacology of medications is reviewed when there is at least phase IIb or phase III evidence of efficacy or approval for use in clinical practice.

- 1.

The most effective treatments of IBS remain those that influence bowel function.

- 2.

Effective secretagogues, lubiprostone and linaclotide, accelerate small bowel and colonic transit and relieve abdominal symptoms as well as bowel dysfunction in IBS.

- 3.

Despite meta-analyses of antidepressants in IBS, the pharmacodynamics and clinical trial evidence of efficacy of antidepressants are limited.

- 4.

Probiotics tend to relieve bloating, flatulence, and, possibly, pain in IBS.

- 5.

Nonabsorbable antibiotics, such as rifaximin, persist for some weeks after cessation of therapy; efficacy is unrelated to result of sugar substrate–hydrogen breath test.

Dyspepsia: current treatment

Patient history and physical examination allow distinction of dyspepsia from symptoms that are suggestive of esophageal, pancreatic, or biliary disease in the majority of cases. Specific attention should be given to elicit a history suggestive of heartburn or a word picture that adequately describes the heartburn. The presence of frequent and typical reflux symptoms should lead to a provisional diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) rather than dyspepsia, and patients should initially be managed as patients with reflux disease. In addition, the use of prescription and nonprescription medications should be reviewed, and medications commonly associated with dyspepsia (especially nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) should be discontinued, if possible.

Assessing the presence of alarm symptoms is also recommended, although this has not been shown to be helpful in distinguishing functional from organic causes of dyspepsia. Patients with typical dyspeptic symptoms and no alarm symptoms are referred to as having uninvestigated dyspepsia and are managed empirically. Most guidelines advocate prompt endoscopy when there are risk factors, such as NSAID use, age above a threshold (eg, 45–55 years), and alarm symptoms, including unintended weight loss. The finding of organic disease at endoscopy determines further treatment, but when the endoscopy is negative, which is the case in approximately 70% of patients, a diagnosis of FD is made. Endoscopy is also advocated in patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia who fail to respond favorably to empiric management.

Therapy in Uninvestigated Dyspepsia

The optimal management strategy for uninvestigated dyspepsia is a matter of ongoing debate and is influenced by population prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, cost of medications, and ease of access to endoscopy. The available options include (1) prompt endoscopy, followed by targeted medical therapy; (2) noninvasive testing for H pylori infection, followed by treatment based on the result (test and treat); or (3) empiric antisecretory therapy.

Several randomized controlled trials have compared prompt endoscopy with empiric noninvasive management strategies and none has shown cost-effectiveness of the prompt endoscopy approach. The available data, therefore, do not support early endoscopy as a cost-effective initial management strategy for all patients with uncomplicated dyspepsia. Nevertheless, most available practice guidelines advocate initial endoscopy in all patients above a certain age threshold, usually 45 to 55 years old, to detect potentially curable upper gastrointestinal malignancies.

Because of the involvement of H pylori infection in peptic ulcer disease, several consensus panels advocate noninvasive testing for H pylori infection in young patients (below 45–55 years) with uninvestigated dyspepsia. Patients with a positive test result receive therapy to eradicate H pylori, with a frequently advocated regimen containing a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and two antibiotics, such as amoxicillin and clarithromycin, taken twice daily for 10 to 14 days. In contrast, patients with a negative test result are treated empirically, usually with a PPI. The benefits of this test and treat strategy are the cure of peptic ulcer disease, the prevention of future peptic ulcers, and the cure of a small subset (less than 10%) of patients in whom FD symptoms seem H pylori related. Initial empiric antisecretory therapy is attractive because it controls symptoms and lesions in most patients with underlying GERD or peptic ulcer disease and may be beneficial for up to one-third of patients with FD. Although earlier cost-efficacy models, assuming a high prevalence of GERD or peptic ulcer disease, suggested a benefit with the empiric antisecretory therapy, recent economic models suggest that the test and treat approach may be equally or less cost-effective compared with empiric antisecretory therapy.

Taken together, the test and treat approach remains attractive for young dyspeptic patients in a population with a high prevalence (>20%) of H pylori infection. In those who are H pylori negative, empiric PPI is started for 1 to 2 months. In populations with a low H pylori prevalence, empiric antisecretory therapy (a PPI for 1 to 2 months) is the preferred option. Those who fail to respond to these initial approaches, and probably also those with symptom recurrence after stopping antisecretory therapy, should undergo endoscopy, although the yield is likely to be low.

Therapy in Functional Dyspepsia

Lifestyle (avoiding caffeine, alcohol, and NSAIDs) and dietary (eating more frequent smaller meals and avoiding fatty or spicy meals) measures are usually prescribed to FD patients but, due to lack of studies, there is no firm evidence of benefit. For many patients, pharmacotherapy is considered, but proof of efficacy to date is limited.

Antisecretory therapy

Meta-analyses of antisecretory therapy in FD have demonstrated significant efficacy of H 2 receptor antagonists and PPIs whereas antacids, sucralfate, and misoprostol were not beneficial. A significant benefit was found for H 2 receptor antagonists over placebo with a relative risk reduction of 23% and a number needed to treat of 7, but many of these trials probably included GERD patients in a broad interpretation of the diagnosis of dyspepsia. A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled, randomized trials with PPIs in FD also confirmed efficacy with a number needed to treat of 10 and a relative risk reduction of 13%. These numbers are lower than for H 2 receptor antagonists, but this probably reflects more stringent inclusion of true FD and exclusion of GERD, rather than less efficacy for PPIs. No difference in efficacy was found between half-dose, full-dose, or double-dose PPIs. PPI therapy is most effective in the group with overlapping reflux symptoms, less effective in the epigastric pain group (probably EPS according to Rome III definition), and not superior to placebo in FD with dysmotility symptoms (probably PDS according to Rome III).

Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy

A Cochrane meta-analysis reported a 10% pooled relative risk reduction compared with placebo at 12 months of follow-up, with a number to treat of 14. The impact of eradication therapy in FD remains limited, partly because of the low yield and the lack of a short-term symptomatic benefit. Moreover, in Western populations, the prevalence of H pylori infection is steadily declining, and the prevalence of H pylori positivity in FD patients is below 20% in many series.

Prokinetic agents

Gastroprokinetics are a heterogenous class of compounds, which act through different types of receptors to enhance gastric motor activity. Meta-analyses suggest superiority of prokinetics over placebo in FD, with a relative risk reduction of 33% and a number needed to treat of 6, but this is mainly based on studies with domperidone and cisapride, and there is a suggestion of publication bias. Domperidone, a dopamine-2 receptor antagonist, and cisapride, a 5-HT 4 receptor agonist, stimulate gastric motility by facilitating the release of acetylcholine from the enteric nervous system. Cisapride, however, has been withdrawn because of safety concerns and domperidone is not widely available.

More recent studies with other types of prokinetic agents have generally failed to provide substantial symptom relief in FD. Controlled trials in FD have been conducted with newer 5-HT 4 agonists, including mosapride, which failed to show benefit, and tegaserod, with which a small benefit of unlikely clinical significance was found in the phase 3 studies. Itopride, a mixed dopamine-2 receptor antagonist/cholinesterase inhibitor, seemed beneficial in a phase 2 study, but this was not confirmed in phase 3 studies. ABT-229, which is prokinetic acting through agonism at the motilin receptor, actually worsened FD symptoms compared with placebo when administered at high doses.

Psychotropic agents

Although systematic reviews suggest that anxiolytics and antidepressants, especially tryciclic antidepressants, may have some benefit in treating FD (pooled relative risk reduction of 45%), the available trials are small and of poor quality, and publication bias cannot be excluded. The mechanism of action of antidepressants is unclear, because symptomatic relief from these medications seems independent of the presence of depression, and no significant effects of antidepressants on visceral sensitivity have been established in FD. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), paroxetine, enhanced gastric accommodation in healthy subjects, but clinical studies evaluating this class of agents in FD are lacking. A large controlled trial with the SSRI and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, venlafaxine, in FD failed to show any benefit.

Psychological therapies

Although clinical trials of psychological interventions (such as hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and relaxation training) for FD claim benefit, these studies suffer from inadequate blinding, biased patient recruitment, and problematic statistical analysis. Moreover, not all patients are motivated for psychological interventions, and it is often difficult to find therapists with experience and interest in this particular area.

Investigational drugs

Novel targets in the treatment of FD are impaired gastric accommodation and visceral hypersensitivity, using fundic relaxants or visceral analgesics. Although nitrates, sildenafil and sumatriptan, can relax the proximal stomach, they seem less suitable for therapeutic application in FD. Several serotonergic drugs are also able to enhance gastric accommodation, including 5-HT 1A receptor agonists and 5-HT 4 receptor agonists. A clinical trial with the anxiolytic 5-HT 1A receptor agonist, tandospirone, showed significant benefit over placebo, whereas the novel 5-HT 1A receptor agonist, R137696, failed to show any symptomatic benefit. Z-338 (acotiamide) is a novel compound that enhances acetylcholine release via antagonism of M1 and M2 muscarinic receptors. In a pilot study, acotiamide showed potential to improve FD symptoms and quality of life through a mechanism that may involve enhanced gastric accommodation.

Visceral hypersensitivity is another attractive target for drug development. The principal drug classes under evaluation are neurokinin receptor antagonists and peripherally acting κ-opioid receptor agonists. The κ-opioid agonist, fedotozine, showed potential efficacy in FD, but development of this drugs was discontinued. More recently, asimadoline, another κ-opioid receptor agonist, failed to improve symptoms in a small pilot study in FD.

Practical management approach

In FD patients with mild or intermittent symptoms, reassurance, and some lifestyle advice may be sufficient. In those who do not respond to these measures, or those with more severe symptoms, drug therapy can be considered. Testing for H pylori infection is recommended and, if positive, should be followed by eradication therapy. An early impact on symptoms beyond a reassurance and placebo effect is unlikely, and any symptom benefit, if present, is only obtained after several months of follow-up. Both PPIs and prokinetics can be used in initial pharmacotherapy. The symptom pattern may help in determining the most appropriate initial choice, but a change of drug class is advisable in case of insufficient therapeutic response (see Fig. 1 ).

A 4- to 8-week trial of PPI therapy is the first-line approach in all patients with coexisting heartburn and can also be considered in those with EPS (see Fig. 1 ). In the case of symptomatic relief, interruption of treatment should be tried and intermittent or chronic therapy can be used for patients with repeated relapses. In PDS, a prokinetic drug can be considered as the first approach. In cases of insufficient response, a switch between PPI and prokinetic drugs can be considered. Although in theory combinations of PPIs and prokinetics may have additive symptomatic effects, single-drug therapy is preferable. In patients with bothersome symptoms that persist in spite of these initial therapies, a trial of a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant may be considered, even in the absence of overt anxiety or depression, whereas SSRIs and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors are probably best avoided in FD. Referral to a psychiatrist or psychotherapist can be considered in those with obvious coexisting psychiatric disease or those with a history of abuse or with a debilitating impact of FD symptoms on their daily functioning.

Irritable bowel syndrome: current treatment

The diagnosis of IBS is based primarily on the recognition of the constellation of symptoms, typically the concomitant presence of abdominal discomfort or pain in association with alteration of bowel movement frequency, consistency or ease of passage, or completeness of evacuation of bowel movements. Bloating is often present in IBS, and there is overlap with many other functional disorders, including FD and heartburn. The presence of blood passed per rectum, weight loss, or a significant change in the characteristics of the symptoms after a stable pattern over many years constitutes alarm features that necessitate further investigation, including imaging and biopsy of the colon. In the vast majority of patients, a diagnosis of IBS is safe in the absence of alarm features. In a cohort of patients with IBS-D and IBS-C, 46% had accelerated transit, and 20% delayed colonic transit respectively. There is also significant overlap between symptoms of IBS-D and microscopic colitis, which is identifiable with colonic mucosal biopsies and responds well to budesonide treatment. Thus, although it is reasonable to use a symptom-based diagnosis and empiric first-line therapies (such as fiber, osmotic laxatives, or opioids, as needed), when patients first present to a primary care physician, it is important to exclude the other diagnoses or evaluate patients further, if they are not responding to treatment. For example, Voderholzer and colleagues showed that if patients with constipation do not respond to fiber supplementation, they are likely to have medication-induced or slow transit constipation or an evacuation disorder.

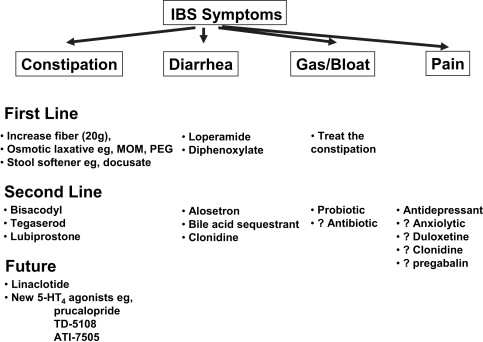

In general, IBS therapy follows the approaches in see Fig. 2 . It is often best to focus on the predominant symptom: diarrhea, constipation, or pain/gas/bloat.

First-Line Therapies

The first-line treatment for diarrhea in IBS is loperamide (2 mg); although the general recommendation is to administer one capsule after each loose bowel movement, this may be insufficient or it may lead to rebound constipation. Because many patients experience bouts of diarrhea lasting days, but it is not consistent every day, or patients may experience postprandial diarrhea, another approach is to administer loperamide (2 mg) on awakening in the morning for periods when patients experience loose movements and 2 mg 15 minutes before meals to try to avoid postprandial diarrhea. The liquid formula provides a convenient way to titrate the dose of loperamide, up to a maximum of 16 mg per day.

Diphenoxylate is an alternative to loperamide; caution is necessary because some preparations also contain atropine, which may result in undesirable anticholinergic side effects. There is no evidence that fiber relieves diarrhea in IBS.

The first-line treatment for constipation in IBS is fiber (12 to 20 g per day) in the form of dietary fiber or supplements. Several studies actually show that fiber aggravates several symptoms of IBS, including bloating. For this reason, an alternative first-line therapy for constipation in IBS is the class of osmotic laxatives, such as magnesium salts (typically 1 g up to 4 times per day) or polyethylene glycol (typically 17 g in 240 mL water up to twice per day).

The first-line treatments for abdominal pain or discomfort in IBS, especially if unrelieved after relief of constipation or antidiarrheal treatment, are the anticholinergic antispasmodics. These are typically used on an as-needed basis (eg, dicyclomine [0.125 mg orally or sublingually] or [in Europe] otilonium bromide or mebeverine). This class of drugs was recently the subject of a meta-analysis that suggested some agents (eg, peppermint oil) are effective, although the trials are small, of low quality, or require replication.

Second-Line Treatments

If loperamide fails to control the diarrhea associated with IBS, and a patient continues to have significant symptoms, bile acid malabsorption should be considered and either screened with serum 7αC4 measurement or diagnosed with the Se-selenomethionine retention test. If these tests are not available, a therapeutic trial with cholestyramine (12 g per day) or colesevelam (1.875 mg once or twice daily) should be performed. If there is no relief of the diarrhea, the bile acid sequestrant should be stopped and a therapeutic trial with alosetron (0.5 mg once or twice daily) may be considered in accordance with the Food and Drug Administration guidance documents in the United States. This medication is not available in most countries. Patients should be informed about the risk of ischemic colitis and should be advised to inform the physician if there is rectal bleeding.

If first-line treatments for constipation fail, there are two potential approaches. First, use of a simple stimulant laxative, such as bisacodyl, which has been shown effective in stimulating colonic transit ; a colonic prokinetic (in Europe, prucalopride is approved for chronic constipation not responsive to laxatives); or an intestinal secretagogue, specifically lubiprostone starting at a dose of 8 μg twice a day. The highest approved dose in chronic constipation is 24 μg twice a day. Approximately 20% of patients experience nausea with lubiprostone. A novel secretagogue that is promising, but not yet approved, is the guanylate cyclase C agonist, linaclotide.

Second, if the pain or discomfort does not respond to antispasmodics, many physicians prescribe antidepressants: low-dose tricyclic agents to avoid development or aggravation of constipation or standard doses of SSRIs ( Fig. 3 ). There is growing appreciation that the latter medications may not be as innocuous as claimed; because they are frequently associated with sexual dysfunction, such as anorgasmia, at least 30% of men and women experience anorgasmia from antidepressant drugs with serotonin agonist activity, and there is some evidence that they may affect bone density. If a patient’s predominant discomfort is bloating, a trial of probiotics (single species or combination) may be indicated. Single trials have been associated with evidence of marked benefit, and meta-analyses are supportive, although this is controversial. There is increasing evidence that the nonabsorbable antibiotic, rifaximin, results in overall IBS relief and relief of bloating in phase IIB trials. In patients with severe abdominal pain, some physicians prescribe antipsychotic medications or pregabalin, although the evidence is based only on open-label or pharmacodynamic trials.