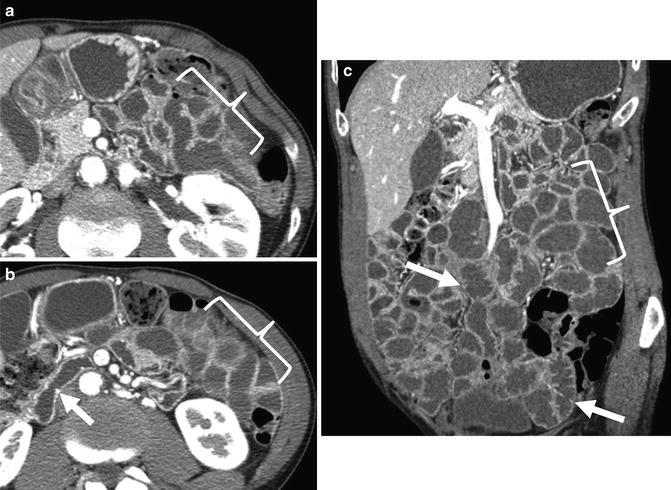

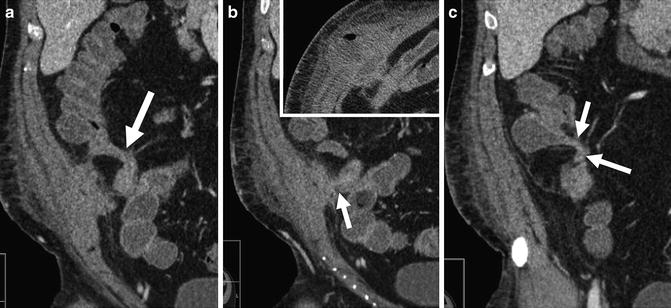

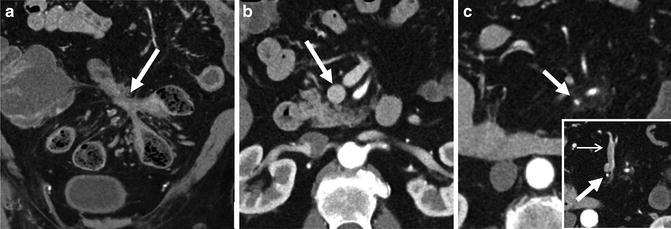

Fig. 4.1

Normal appearance of jejunum at CT enterography. Note thin and regularly spaced valvulae conniventes in distended jejunum (a). Collapsed jejunum in another patient at CT enterography (b) shows normal appearance as lumen collapses and jejunal folds coapt together. Forty minutes after CT in (b), patient underwent MR enterography showing normal jejunal loops and folds (c)

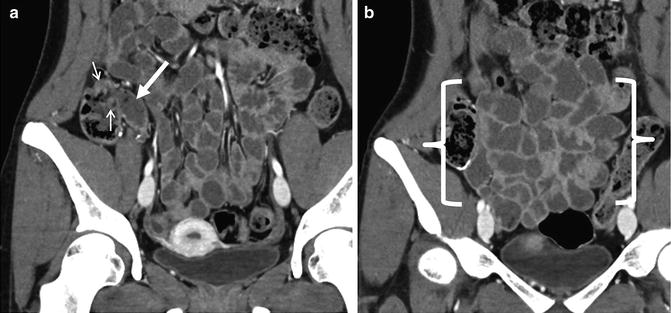

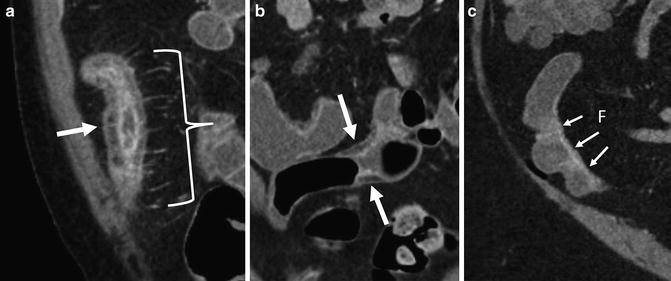

Fig. 4.2

Coronal CT enterography images showing normal appearance of terminal (a, arrow) and distal (b, between brackets) ileum. Note paucity of folds, thin wall, and slightly decreased mural enhancement. Small arrows (a) show ileocecal valve, which is located within a haustral fold in the cecum

Mural Findings

Mural hyperenhancement is generally seen in the presence of mural thickening, and it is a nonspecific sign of inflammation or altered perfusion. The combination of segmental mural hyperenhancement and mural thickening is specific for Crohn’s disease when the enhancement and mural thickening are asymmetric with respect to the bowel lumen—for example, worse along the mesenteric border (Fig. 4.3). Similar to findings at small bowel follow-through where the mesenteric border linear ulcers are pathopneumonic for Crohn’s disease, inflammation as represented by CT findings of hyperenhancement and mural thickening are seen most prominently along the mesenteric border, often with pseudosacculation along the anti-mesenteric border, with prominent vasa recta that supply the inflamed bowel segment. Jejunal Crohn’s involvement occurs in about 15 % of Crohn’s patients, is associated with an increased incidence of stricturoplasty and hospitalizations [17], and is frequently overlooked by novice radiologists and gastroenterologists (Figs. 4.4 and 4.5). While there are a number of other causes of segmental jejunal hyperenhancement and mural thickening, including infection (often giardia), ulcerative jejunitis in sprue, vasculitis, and systemic infiltrating diseases, only Crohn’s disease typically involves the bowel in an asymmetric fashion (whether proximal or distal). Segmental hyperenhancement without wall thickening can be seen in early Crohn’s disease, as well as other causes of hyperenhancement, and generally reflects more mild degrees of inflammation. Radiation enteritis and NSAID-related diaphragm disease also demonstrate segmental hyperenhancement in conjunction with focal strictures in the mid to distal small bowel. Both types of strictures are short (often 1–2 cm) and symmetric with respect to the bowel lumen [18, 19]. Strictures in the setting of radiation enteritis occur in small bowel with abnormal enhancement, while those in diaphragm disease have variable (often mild) hyperenhancement with intervening regions of normal-appearing bowel. Celiac sprue typically manifests as normally enhancing jejunal loops that have lost valvulae conniventes due to villous atrophy, usually with fold reversal (or increased number of folds) in the ileum (Fig. 4.6). Hypoenhancing bowel can be a worrisome finding for ischemia, and when pneumatosis is present, infarction is often present. As ischemia generally frequently occurs in the setting of high-grade small bowel obstruction or vascular occlusion, pneumatosis cystoides coli and benign pneumatosis are not infrequently observed in outpatient CTE (Fig. 4.7). Focal regions of wall thickening with hypo- or isoenhancement may also represent intramural hemorrhage or lymphoma (described later) [20].

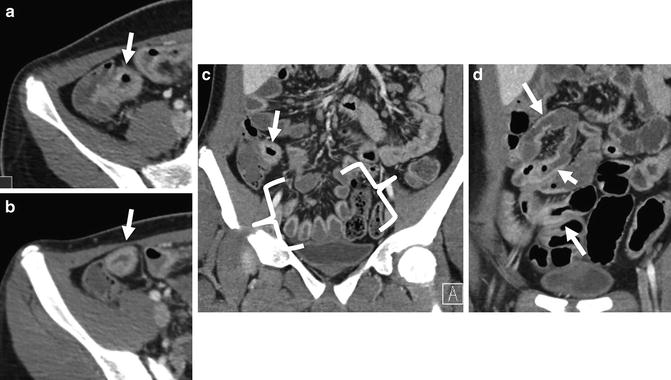

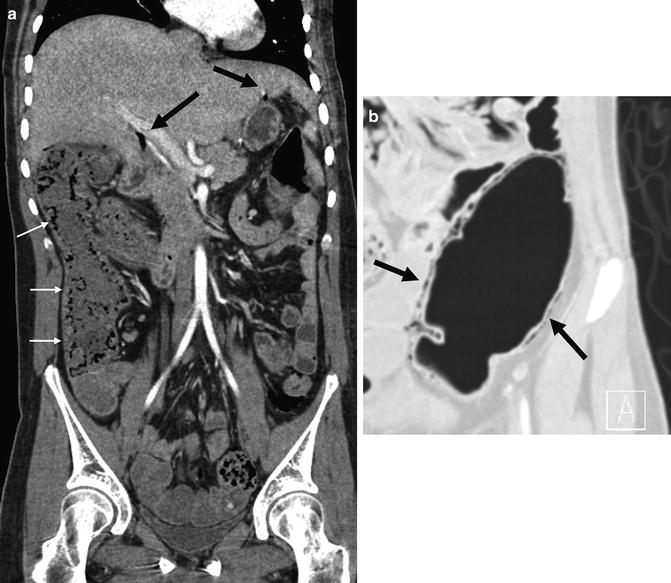

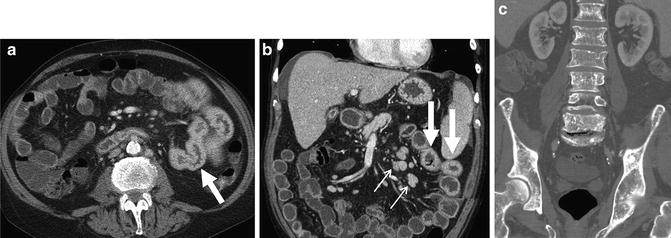

Fig. 4.3

Typical appearance of Crohn’s ileitis at CT enterography in patient with erythematous mucosa at ileoscopy. Note mural thickening and hyperenhancement of terminal ileum on axial and coronal images (a–c, arrows). In distal ileal loops, inflammation as demonstrated by hyperenhancement and wall thickening is more prominent along the mesenteric border (c, between brackets), so is asymmetric with respect to bowel lumen. Multiple skip lesions (d, arrow) are present in the mid-ileum. Findings demonstrate the complementarity of CT enterography with endoscopic assessment. Biopsy at ileoscopy showed active and chronic ileitis

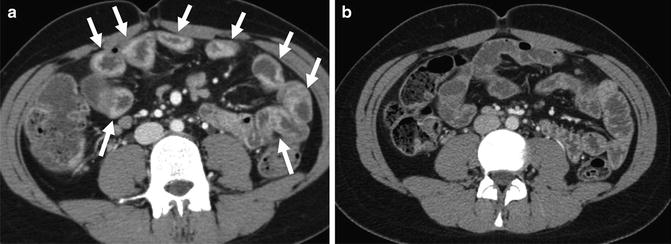

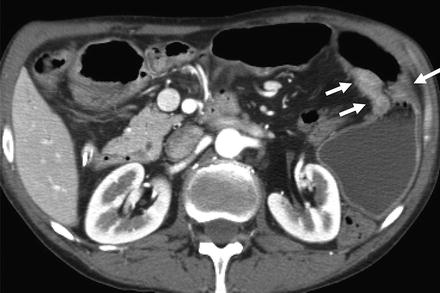

Fig. 4.4

Typical findings of jejunal Crohn’s disease in 18-year-old Crohn’s patient with asymmetric thickening and hyperenhancement of multiple loops (a, arrows). After combination therapy (infliximab combined with azathioprine), CT enterography 2 years later demonstrates normal appearance to the previously inflamed jejunal loops (b)

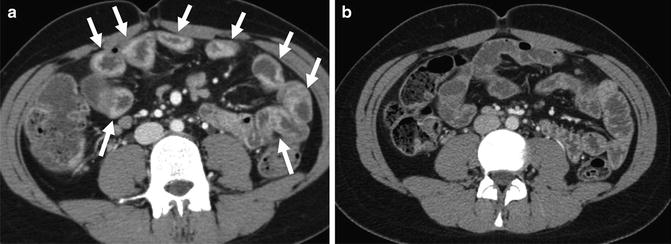

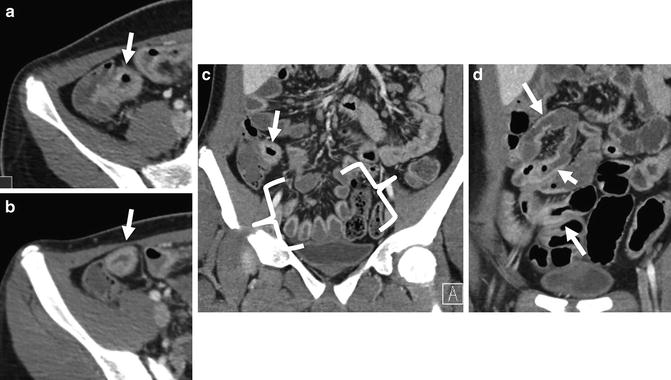

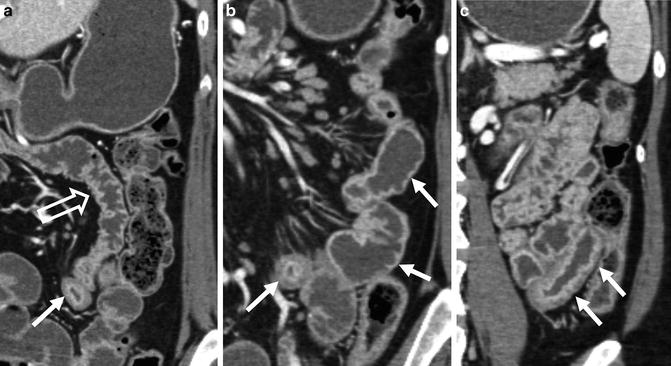

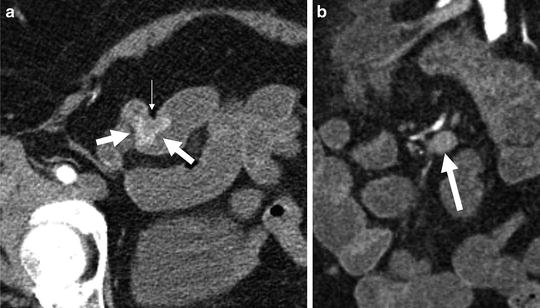

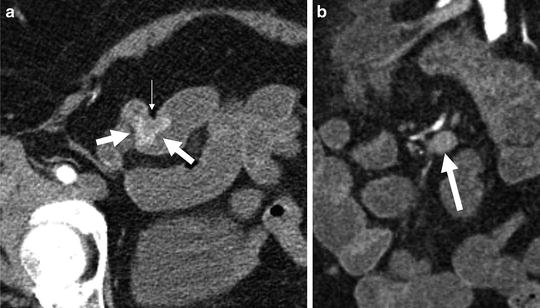

Fig. 4.5

CT enterography images from another patient with jejunal Crohn’s disease show normal-appearing jejunum (open arrow, a) superior to inflamed jejunum (a, solid white arrow). Note prominent vasa recta along mesenteric border of other jejunal loops (b, arrows), in addition to disruption of fold pattern and asymmetric enhancement. Some inflamed loops have a layered or stratified appearance to the thickened bowel wall (a–c, arrow)

Fig. 4.6

CT enterography images demonstrating typical findings of celiac sprue, including normally enhancing jejunal loops with loss of folds (a–c, brackets). Note featureless duodenum (b, arrows) and increased number of folds in the ileum (fold reversal; c, arrows)

Fig. 4.7

Pneumatosis is observed throughout the ascending colon (a, small white arrows), with a small amount of free air underneath the liver (a, black arrows) on CT enterography performed for anemia. Coronal image of sigmoid colon also shows pneumatosis (b, black arrows). Patient was observed in hospital without treatment without deterioration. Imaging findings felt to represent benign pneumatosis potentially due to pseudo-obstruction or multiple prior enteroenteric anastomoses

Mural thickening is generally considered to be present when greater than 3 mm in a distended bowel segment. When segmental mural thickening is combined with segmental hyperenhancement, findings usually reflect inflammatory or infectious etiologies. Symmetrical involvement in the proximal small bowel can be seen in ulcerative jejunitis and/or infectious jejunitis, such as neutropenic enteritis or giardia. For ulcerative jejunitis, other findings such as relative loss of valvulae conniventes are helpful. Symmetrical mural thickening combined with straightened and dilated bowel loop is often seen in ACE-related angioedema, venous compromise (such as from SMV thrombosis or carcinoid tumor), or pancreatitis. ACE-related angioedema is usually seen in women and may or may not be associated with first exposure to an ACE inhibitor. It is manifest by general bowel wall edema, and segmental luminal dilation, often with localized ascites and mesenteric edema [21]. Hyperenhancement of affected loops is normal or relatively mild with symmetric bowel wall edema present. SMV thrombosis, and segmental hemorrhage in anticoagulated patients, can also present with long segment mural thickening with or without hyperenhancement, and correlative findings in the SMV or solid organs should be searched for. Infiltrating diseases such as systemic IgG-related disease, mastocytosis, and amyloidosis are rarely seen, but they can also cause segmental bowel wall thickening (Fig. 4.8). In general, for inflammatory, vascular, and infiltrative diseases, the bowel wall thickening will be less than 1.5 cm in diameter; neoplasm should be considered for focal regions of bowel wall thickening of greater degree [22]. Diffuse small bowel thickening can be seen in cirrhosis, graft-versus-host disease, and shock bowel, where correlation with patient history and other imaging findings usually suggests the diagnosis. Diffuse hyperenhancement of the bowel with mild and symmetric wall thickening is seen in conjunction with CT signs of hypotension (e.g., flat IVC) in patients with trauma-induced shock bowel, but similar findings are seen in other conditions such as septic shock and cardiac arrest that cause hypotension [23].

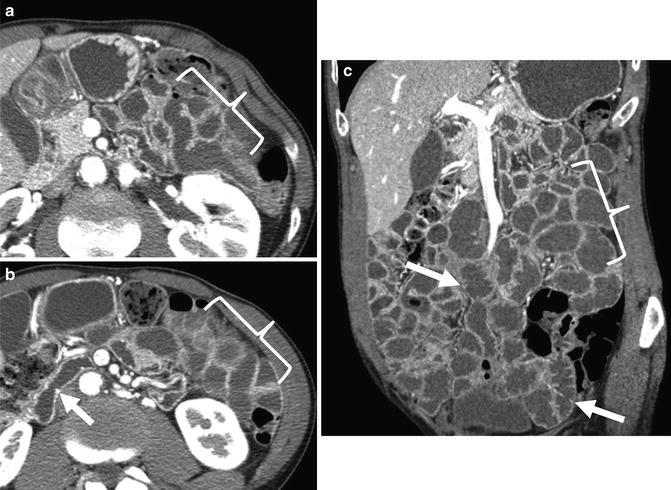

Fig. 4.8

Diffuse and continuous jejunal mural thickening and enhancement (a and b, arrows) due to mastocytosis. Note mesenteric adenopathy (small white arrow, b), small amount of ascites (b), and diffuse sclerotic lesions in the bones (c)

Focal mural findings in the small bowel are generally neoplastic or vascular, whereas luminal findings include active bleeding and polyps or neoplasia. While adenocarcinoma is generally considered one of the more common small bowel neoplasms, carcinoid (neuroendocrine) tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), and lymphoma are much more frequently seen at cross-sectional enterography. Now that multiphase CTE is often performed to evaluate for obscure GI bleeding, the unique morphologies of many of these tumors are being better appreciated.

Carcinoid tumors can appear as small hyperenhancing polyps, which grow within the bowel wall and over time will often become flat or plaque-like masses, often with luminal shouldering and serosal puckering or retraction (Figs. 4.9 and 4.10) [24]. Multifocal neuroendocrine tumors are frequently seen and are clustered within a small bowel (usually ileal) segment. As the tumor infiltrates through the vessel wall, typical patterns of metastatic lymphadenopathy are seen (Fig. 4.10). Neuroendocrine mesenteric and nodal metastases will often cluster along the regional mesenteric vessels and eventually cause vascular compromise. Eventually, liver metastases will develop.

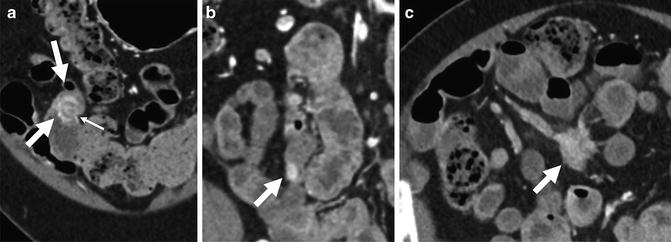

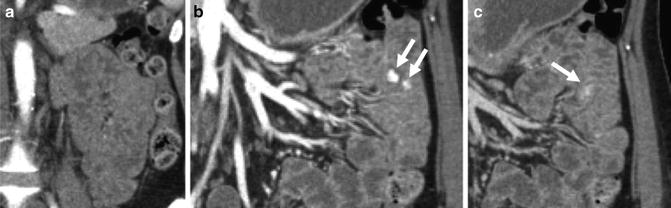

Fig. 4.9

Multiphase CT enterography performed for obscure GI bleeding demonstrates an enhancing ileal tumor (a, arrows). The mass demonstrates intense enhancement and serosal puckering (small white arrow), which is indicative of carcinoid tumors. Nodal metastases from carcinoid tumors typically occur close to mesenteric vessels (b, arrows)

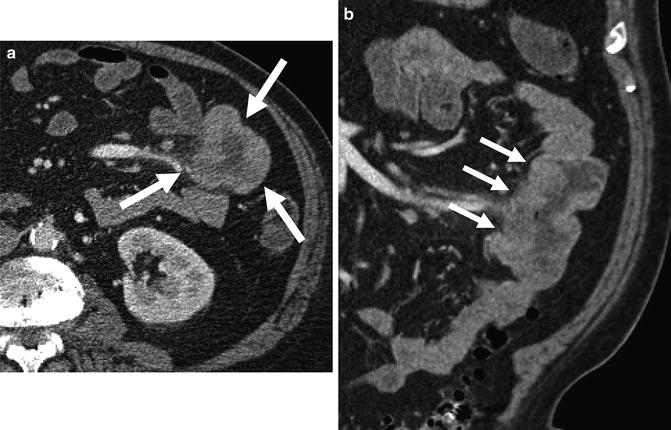

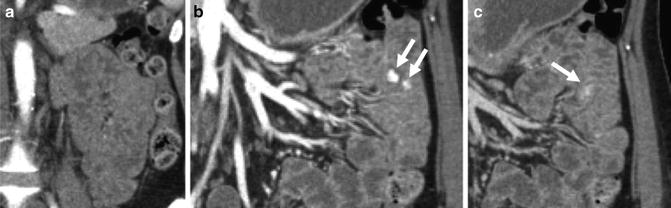

Fig. 4.10

CT enterography performed for abdominal pain shows multiple enhancing ileal masses (a and b, arrows), one with characteristic serosal puckering (a, small arrow), indicating multifocal ileal carcinoid tumors. Mesenteric nodal metastasis (c, arrow) demonstrates typical findings of enhancing mesenteric mass with radiating strands of desmoplasia to nearby small bowel loops and engorged mesenteric veins (due to obstruction)

GIST tumors are generally hyperenhancing tumors, often with an exoenteric component, and may or may not show surface ulceration (Fig. 4.11). In contradistinction, some GIST tumors can be isoenhancing and intraluminal. Frequently, as the GISTs enlarge, they ulcerate and may lose typical hyperenhancement patterns. It may be useful to characterize the morphology of these masses with positive enteric contrast when needed. Occasionally, ectopic pancreas can mimic the appearance of GIST tumors in the proximal small bowel, as the ectopic tissue will also be exoenteric with respect to the bowel lumen.

Fig. 4.11

Typical appearance of small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST; arrow) at CT enterography. Axial image shows 2 cm hypervascular mass with intraluminal and exoenteric components

Small bowel lymphomas occur as singular or multiple areas of focal bowel wall thickening. Unlike carcinoid or GIST tumors and Crohn’s disease, lymphomas typically are iso- or hypoenhancing compared to the adjacent bowel wall. The classic pattern for lymphoma is that of “aneurysmal ulceration,” meaning that the lumen of the small bowel tumor is markedly enlarged with thickening of the surrounding wall (Fig. 4.12) [25]. There will often be adjacent lymphadenopathy. Adenocarcinoma can be seen in isolation or in the setting of Crohn’s disease, where it can appear as a focal stricture with mural nodularity (Fig. 4.13) [26]. Adenocarcinomas are infrequently detected at CTE and do not demonstrate a characteristic morphology.

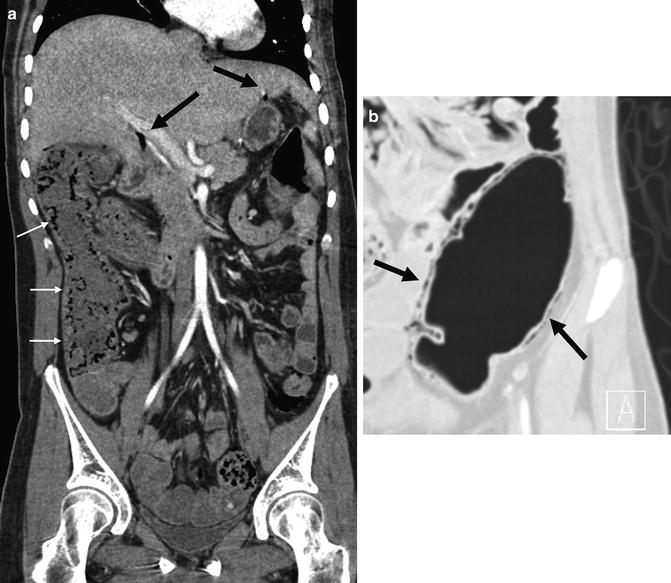

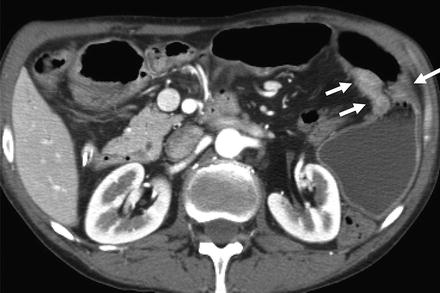

Fig. 4.12

Small bowel lymphoma (a and b, arrows) with marked wall thickening caused by iso- or hypo-attenuating tumor and enlargement of the bowel lumen (referred to as “aneurysmal ulceration”)

Fig. 4.13

Adenocarcinoma (arrows) arising in setting Crohn’s disease in a patient with multiple strictures. Note high-grade partial obstruction and nodularity to the extraluminal margin

Active bleeding at multiphase CTE is demonstrated by progressive accumulation of intraluminal contrast over subsequent phases of enhancement (Figs. 4.14 and 4.15). Active bleeding may be associated with a neoplasm or vascular etiology, but in the case of a Dieulafoy lesion or focal ulcer, no other abnormality will be appreciated. Several studies have shown that bleeding rates detectable at CT angiography and multiphase CTE are comparable to catheter angiography [14]. Medication and radiopaque debris will also be bright at multiphase CTE, and will be unchanged in appearance between phases when slight movement of luminal contents due to peristalsis is taken into account.

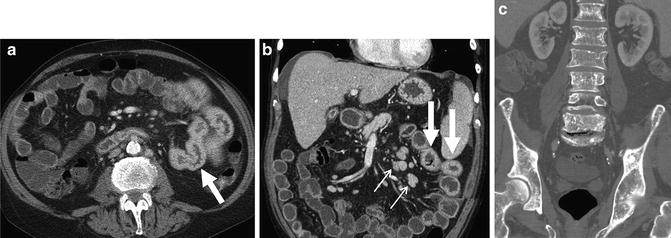

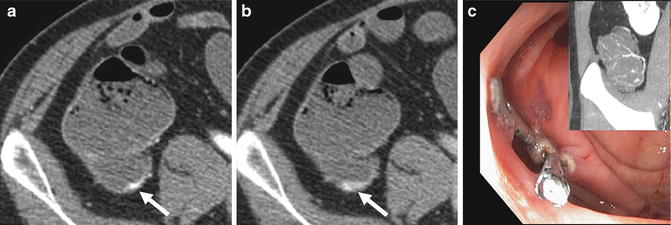

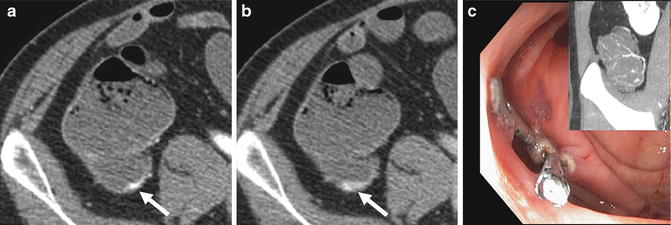

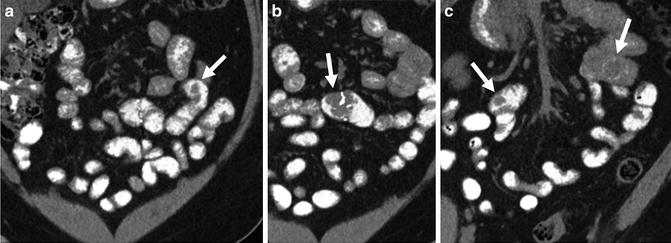

Fig. 4.14

Axial enteric and delayed-phase images (a and b, respectively) demonstrate progressive accumulation of intravenous contrast dependently within the cecum, indicating active bleeding (a and b, arrows). Coronal maximum intensity projection images (c, inset) show nodular tufts of vessels in the wall of the cecum. Patient was treated with argon plasma coagulation and hemoclips

Fig. 4.15

Coronal arterial-, enteric-, and delayed-phase images (a, b, and c, respectively) from a multiphase CT enterography demonstrate progressive accumulation of intravenous contrast within the jejunal lumen between the arterial and enteric phases (b, arrows). Delayed-phase images show movement and dilution of intraluminal contrast (c, arrow). Findings indicate active jejunal bleeding. Small bowel enteroscopy identified a Dieulafoy lesion at this location, which was treated with argon plasma coagulation

Vascular lesions at CTE are generally classified according to the method of Huprich and Yano as angioectasias, arterial lesions, and venous lesions [6]. Angioectasias are frequently multiple and seen in elderly patients. They appear as small or round intramural lesions, usually best seen in the enteric phase of enhancement. They are frequently multiple and are generally underestimated by CT compared to endoscopy. They are thought to arise from mesenteric veins that lack an internal elastic layer, with arteriovenous communication developing as the precapillary sphincter becomes incompetent [6]. Angioectasias and arterial lesions are also seen in the cecum and ascending colon with some regularity at multiphase CTE exam, and in this location, they are generally associated with arterial shunting and an enlarged draining vein. Arterial lesions are best seen in the arterial phase and may or may not have an enlarged draining vein. Because of avid arterial enhancement, there is the potential for large amounts of bleeding. Arterial lesions include angioectasias with arterial shunting, Dieulafoy lesions, and arteriovenous fistulas. Venous lesions are a heterogeneous group of disorders, with varices frequently seen in patients with cirrhosis or chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis from Crohn’s disease. Younger patients often have large congenital vascular malformations, often in conjunction with other known vascular lesions, e.g., Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome (Fig. 4.16).

Fig. 4.16

Large jejunal vascular malformation with phleboliths on precontrast imaging (a, inset), and blood-filled spaces that enhanced slowly with time after contrast (a, arrows), in patient with presumed Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber. Another patient with an ileal vascular malformation with dilated intramural vessels (b, arrows) and a large draining vein (b, inset)

CTE surveillance for polyps and masses can be performed in addition to magnetic resonance (MR) enterography or enteroclysis in patients with polyposis syndromes. In these patients, polyps and neoplasia occur within the lumen, so positive enteric contrast is often used. Because of the high attenuation differences between positive contrast and the filling defects of polyps, radiation doses can be markedly reduced to levels used for CT colonography (Fig. 4.17).

Fig. 4.17

Single-phase CT enterography with positive oral contrast demonstrates multiple polyps (b–c, arrows), including a recurrent polyp (b, arrow). Positive contrast enteroclysis or enterography can be performed at low radiation doses because suspected pathology is known to be located in the small bowel lumen, as opposed to the wall or perienteric tissues

Morphologic abnormalities constitute a heterogeneous group of disorders, including malrotation, small bowel diverticulosis, Meckel’s diverticulum, and postoperative anastomoses. Intestinal malrotation predisposes to midgut volvulus. Findings of small bowel nonrotation include ascending colon and cecum in the midline, redundant duodenum with ligament of Treitz in the right upper quadrant, and rounding of the uncinate process of the pancreas [27]. Patients with non-rotation and intermittent small bowel volvulus often present for outpatient imaging when the small bowel volvulus has resolved. They should be informed of findings so that they can present to the ER if acute, unrelenting pain occurs as prompt surgical treatment may be required.

Small bowel diverticula can be mistaken for a small bowel loop on a single cross-sectional image. In volumetric datasets from CT and MR enterography, the findings are unmistakable, but they are often overlooked. The lumen of the jejunum will have valvulae conniventes, whereas diverticula will not. Jejunal or ileal diverticulitis can occur when a diverticulum becomes inflamed or perforated (Fig. 4.18). Meckel’s diverticulum is a frequent cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding in young and middle-aged patients. Bleeding from Meckel’s can occur due to ulcer, inflammation, neoplasm, or ectopic gastric mucosa within the diverticulum. Often, the diverticulum will be large and may contain a focal area of hyperenhancement or luminal defect corresponding to one of these abnormalities.

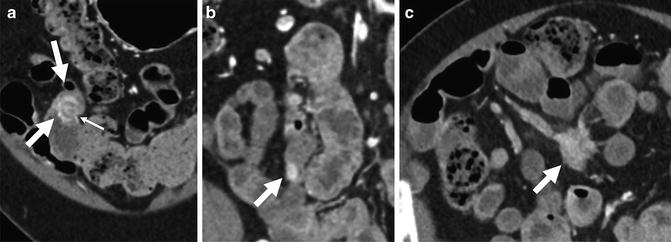

Fig. 4.18

Just superior to two ileal diverticula (a, small arrows), a large ileal diverticulum is seen (b, arrow) with stranding in the surrounding perienteric fat (b and c, small arrows) and localized perienteric air (c, brackets), indicating perforated ileal diverticulitis

Extraenteric Findings

Extraenteric findings can often be an important clue to inflammatory bowel disease or its complications (Fig. 4.19). Penetrating Crohn’s disease is manifest by sinus tracts, fistulae, inflammatory mass, and abscess. Small bowel fistulas (e.g., enterocolic fistula or entercutaneous fistulas) appear as enhancing, extraenteric tracts that arise from inflamed small bowel loops, and often distort or tether loops from which they arise [28]. Complex, branching fistulas will form asterisk-shaped fistulae complexes that will involve multiple small bowel loops (Figs. 4.20 and 4.21). Fistulas that extend to the retroperitoneum will often form abscesses along the iliopsoas muscle. Perianal fistulae suggest Crohn’s disease as the etiology in patients with inflammatory colitis without small bowel involvement. While perianal fistulas and abscesses are often detected at CTE, they are poorly characterized in terms of their anatomic location compared to dedicated perineal MR imaging. Low-kV imaging techniques generally increase the conspicuity of perianal fistulas. Chronic perianal fistulas and anovaginal fistulas are often not seen at CTE.

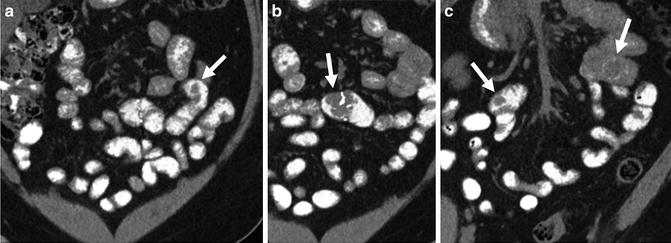

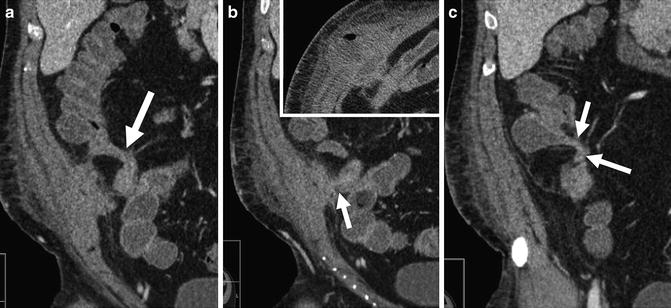

Fig. 4.19

Patient with history of indeterminate colitis underwent CT enterography showing pancolitis with patulous ileocecal valve (a), characteristic of ulcerative colitis. Coronal liver images show mild intrahepatic biliary dilation (b, large arrow) extending inferiorly into the right lobe (b, small arrow) with periductal perfusion abnormalities (b, oval), suggesting cholangitis. Patient underwent ERCP (c) demonstrating a localized stricture at the bifurcation of the intrahepatic ducts and mild changes of intrahepatic primary sclerosing cholangitis

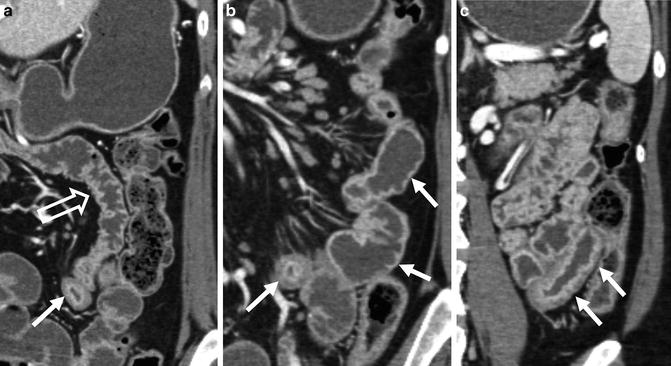

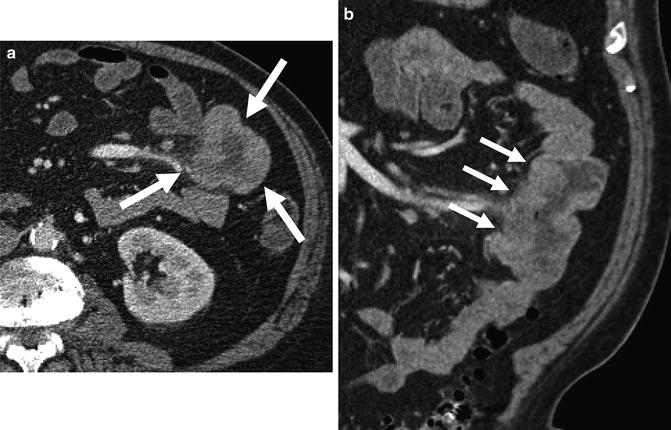

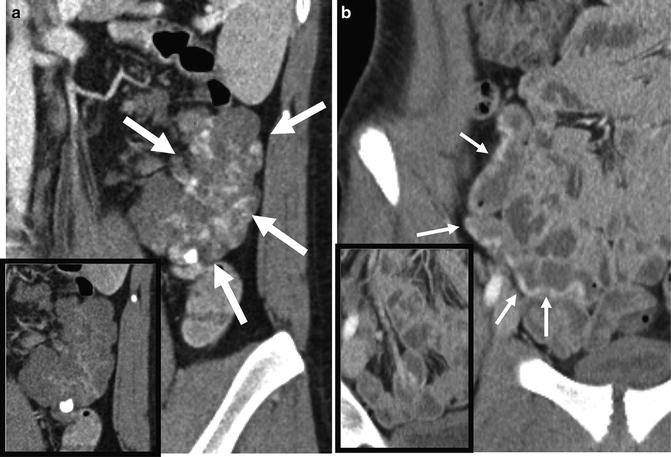

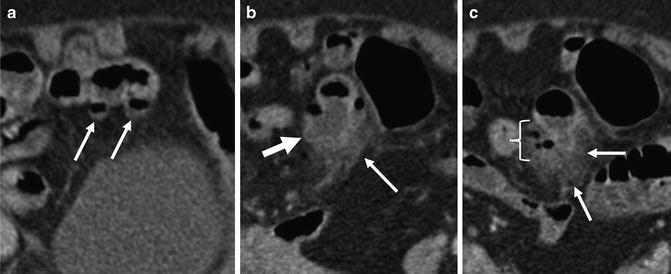

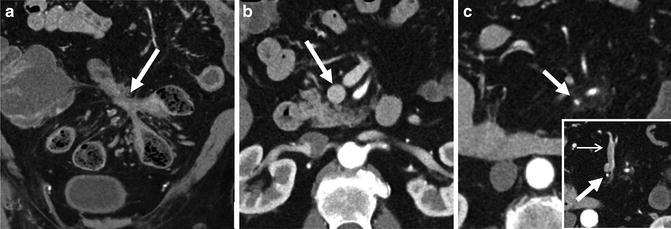

Fig. 4.20

CT enterography images from anterior to posterior demonstrate complex, penetrating ileocolic Crohn’s disease. Fistulas appear as extraenteric tracts with tethering of affected bowel loops (enteroenteric fistula, a—large arrow; ileocecal fistula, c—arrows). Middle image shows fistula to abdominal wall (b, arrow) that has resulted in abdominal wall abscess (b, inset)

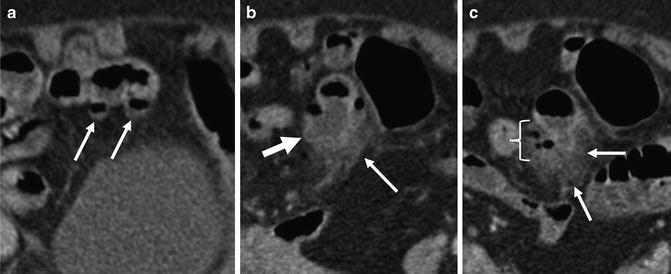

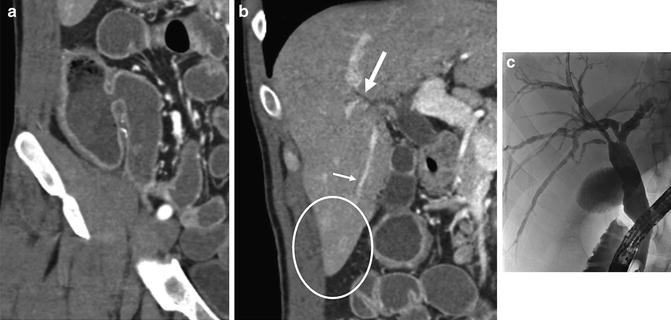

Fig. 4.21

Chronic superior mesenteric vein thrombosis in a patient with asterisk-shaped enteroenteric and enterocolic fistulae complex (a, arrows). Axial images demonstrate normal caliber superior mesenteric vein at the level of pancreatic head (b, arrow) that becomes diminutive inferiorly at the level of transverse duodenum (c, arrow). Even more inferiorly, enlarged peripheral mesenteric venous collaterals are seen (c, inset)

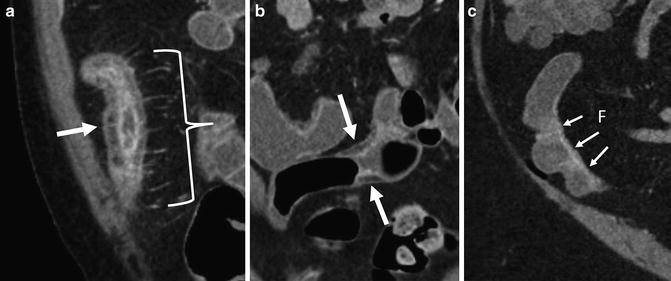

Vascular and mesenteric findings are often associated with Crohn’s disease. The “comb sign” represents engorged vasa recta that supply inflamed bowel segments (Fig. 4.22) and are associated with increased rates of hospitalization and TNF response [29]. Fibrofatty proliferation is often associated with mesenteric border inflammation, and displaces bowel loops (Fig. 4.22). Mesenteric venous thrombosis can be located centrally in the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein, or in smaller, peripheral mesenteric veins. Central mesenteric thromboses frequently completely recanalize, while peripheral ones often result in lasting venous narrowing (i.e., chronic peripheral mesenteric vein thrombosis), and result in collateral vessel formation, including the development of varices (Fig. 4.21) [30].

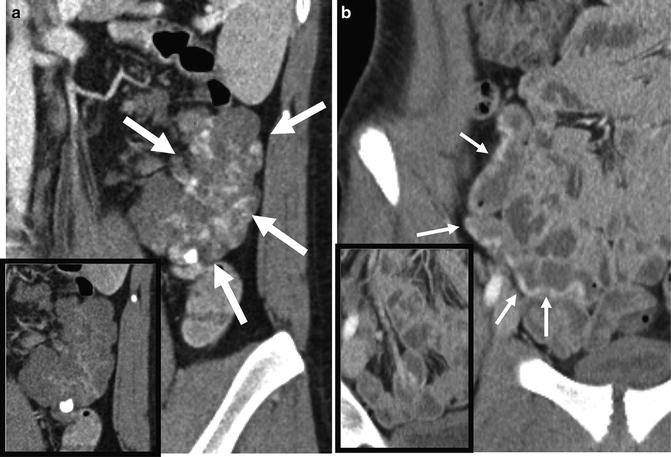

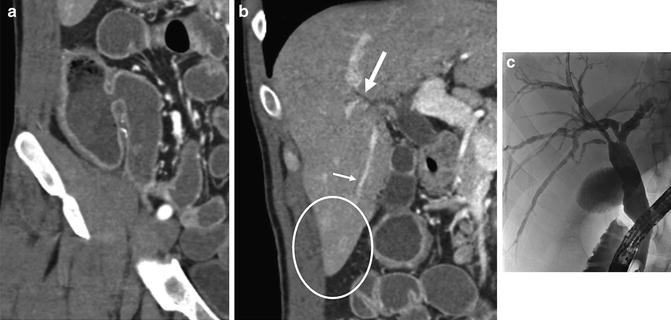

Fig. 4.22

Perienteric and acute and chronic Crohn’s inflammation. Acute and chronic Crohn’s inflammation is evidenced in small bowel loops with mural stratification with synchronous findings of submucosal fat (prior inflammation) and inner wall hyperenhancement (current inflammation; a and b, arrows). The “comb sign” (a, brackets) refers to engorged vasa that enter the small bowel or colon at a right angle (a, bracket). This imaging finding is associated with moderate to severe active inflammation. Mesenteric border inflammation (evidenced by mural hyperenhancement and wall thickening; small arrows, c) in a third patient is also indicative of Crohn’s enteric inflammation, and is associated with anti-mesenteric sacculation and fibrofatty proliferation (“F”)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree