Fig. 19.1

Parks’ classification of fistula-in-ano. Type I, intersphincteric; Type II, transsphincteric; Type III, suprasphincteric; Type IV, extrasphincteric. The terms trans-, supra-, and extra- refer to the external sphincter mass. EAS external anal sphincter, IAS internal anal sphincter, LA levator ani, PR puborectalis. (With permission from: Tiernan JP, Brown Sr. Benign anal conditions: haemorrhoids, fissures, perianal abscess, fistula-in-ano, and pilonidal sinus. Surgery (Oxford) 2011;29(8):382–386)

Fistula classification and location can be very important with regard to selecting the appropriate treatment options in both cryptoglandular and Crohn’s disease patients. Fistulas rarely follow these rules of classification in patients with Crohn’s disease. Even so, males with a low, intersphincteric, posterior Crohn’s fistula may be treated successfully with primary fistulotomy with good success and minimal risk of incontinence. In contrast, women with anterior fistulas have a high risk of incontinence even when treated with superficial fistulotomy and will often require an alternative form of surgical therapy such as a sliding flap repair. Regardless of the position of the fistula around the circumference of the anal canal, high fistulas are less likely to heal, more likely to result in incontinence after treatment, and may require diversion.

Cryptoglandular Fistulas Versus Crohn’s Disease

It may be difficult at times to distinguish between cryptoglandular and Crohn’s fistulas even though the pathogenesis and natural history are very different. This distinction is important to make, as the treatment of these diseases is very different. Fistulas which develop in an atypical location or do not heal regardless of multiple attempts with medical and surgical treatment point to a diagnosis of Crohn’s fistula. Cryptoglandular fistulas are thought to arise from the blockage and infection of one of the anal glands at the dentate line. The gland normally empties into the anal crypt. Abscess formation results in the development of an anal fistula in up to 1/3 of patients. The pathogenesis of Crohn’s fistulas remains poorly understood but is thought to be different than that of the cryptoglandular form. One theory is that a deep anorectal ulcer forms, which subsequently becomes invaded by fecal material and bacteria. The tract is then created by the pressure from the anorectum. Crohn’s fistulas are generally more complex with branching and multiple tracts, which do not follow the typical pattern of cryptoglandular fistulas or Goodsall’s Rule. Unlike patients with cryptoglandular fistulas, Crohn’s fistulas usually do not respond to operative therapy alone. A different algorithm of treatment must be followed with a stronger emphasis on optimal medical management to control rectal disease and reduce the autoimmune inflammatory component of the fistulization.

The possibility that fistulas are due to Crohn’s disease should trigger a search for active disease in the colon or small bowel. Even if intestinal disease is not present, it is possible to distinguish Crohn’s from cryptoglandular fistulas by identifying granulomas in the curettings from the fistula tract or areas of undermined skin. Perianal skin tags may also yield pathognomonic non-caseating granulomas. Zawadzki and colleagues in Sweden reported a unique imaging characteristic on 3D endoanal ultrasound (EUS) for Crohn’s fistulas. This was defined as a hypoechogenic fistula track surrounded by a hyperechogenic area extending into the perianal tissue with a thin, regular hypoechogenic edge. They noted that 20 of 29 (69 %) patients with Crohn’s had a positive Crohn ultrasound fistula sign (CUFS) while 125 out of 128 (98 %) patients with cryptoglandular fistulas did not [1]. This may be a useful, noninvasive method which helps to distinguish Crohn’s fistulas from other forms of perianal disease.

Differential Diagnosis

It is not uncommon (≈20 %) for patients to present with perianal Crohn’s disease as their first symptom. As already mentioned, it can be difficult to distinguish between this and other etiologies of perianal disease. Hidradenitis is a common diagnosis which may be confused with Crohn’s fistulas and may also occur in association with severe perianal Crohn’s disease. Clues to a diagnosis of hidradenitis include additional tracts or abscesses within the groin or armpit, multiple tracts in the perianal skin without connection to the anal canal, and severe disease at onset rather than a gradual worsening in severity over time. Other diagnoses within the differential include cryptoglandular fistula, pilonidal cysts, sexually transmitted diseases, anal fissure, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and anal squamous cell cancer. Knowledge of each of these and heightened suspicion are necessary as one evaluates a patient with unusual findings or presentations.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Undiagnosed patients may present with constant anal pain, pain with defecation, a painless draining perianal skin opening, a painful persistent abscess in the perineum, or unexplained fever. Proper evaluation of the patient includes taking a thorough history with regard to any prior episodes in the past as well as other symptoms of Crohn’s disease including abdominal pain, diarrhea (with or without blood), tenesmus, fevers, or weight loss. A perianal and rectal exam should be performed in the prone jackknife position, looking for fistula tracts, fluctuance, erythema, strictures, or skin tags. An exam under anesthesia (EUA) is necessary if the patient does not tolerate the in-office exam and an anal probe would be used to identify and define the tract and location of the internal opening. If there is difficulty delineating the tract, dilute hydrogen peroxide or betadine may be injected through the external opening in order to aid in locating the internal opening. EUA has long been recognized as the gold standard for identifying tracts and delineating the extent of disease in fistula disease. A lighted Buie Hirschman anoscope is essential to provide good vision in the office while the half circle Hill Ferguson retractor usually gives adequate exposure and vision with reflected light in the operating room. Lighted Hill Ferguson retractors are also available.

A complete evaluation of the rectum should also be performed using either flexible sigmoidoscopy or rigid proctoscopy. Documentation of rectal mucosa involvement is essential to planning treatment. Eventually, colonoscopy should be performed to evaluate the rest of the colon.

Imaging

EUS, MRI, CT, fistulography, and endoscopy have been used in diagnosing and evaluating Crohn’s fistulas. Fistulography is an older imaging modality which involves the injection of contrast into the visible external opening, with subsequent radiography. This technique has fallen out of favor for use in perianal disease as it has been shown to have a low accuracy rate. A retrospective study showed that it was accurate in only four of 25 patients in delineating fistulas compared to operative findings. Fistulography may be helpful in the circumstance of extrasphincteric disease or when used with other modalities. CT has been used for fistula imaging; however, it is limited by lower resolution, artifact, image blurring, streaking due to fistula contents, and an inconsistency identifying the levator ani. CT has not been useful to classify fistulas or guide appropriate treatment [2, 3].

MRI is a proven technique for detecting and delineating fistula tracts. The internal and external anal sphincters are well characterized, and therefore the relationship of the fistula tract to these structures can be determined. Endoanal coils may be used to enhance the resolution of the MRI, though this technique may be limited by patient discomfort. For patients suspected to have complex disease extending into the pelvis, such as in suprasphincteric fistulas, 1 mL of glucagon may be administered intramuscularly to help decrease bowel motion [4]. Fibrotic fistulous tracts will appear hypo-intense on T1- and T2-weighted images and enhance with administration of gadolinium (Fig. 19.2). Fluid and granulation tissue will both appear hyper-intense but only granulation tissue will enhance with gadolinium (Figs. 19.3 and 19.4). Buchanan found that disease recurrence after surgery in patients with fistula-in-ano was decreased by 75 % in those who underwent preoperative MRI [5].

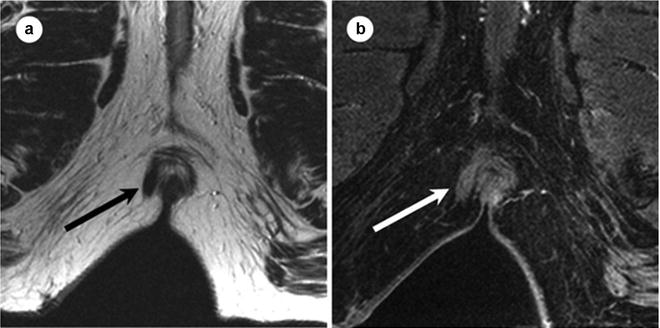

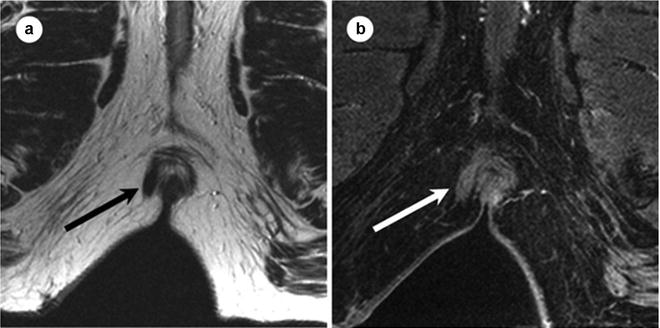

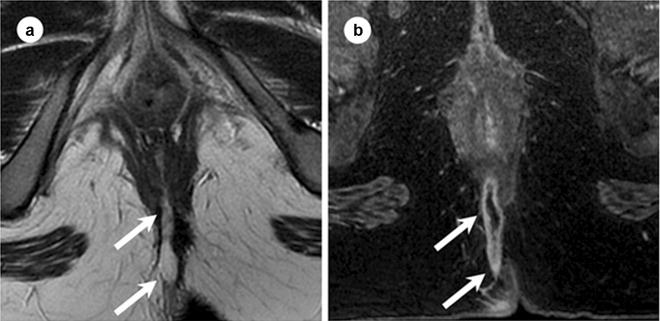

Fig. 19.2

Appearance of fibrotic fistula track at MR. Sixty-three-year-old male with right lateral fibrotic intersphincteric fistula track. Axial T2 FSE (a) and axial T1W SPGR postgadolinium images with fat saturation (b) obtained at 1.5 T below the level of the anal sphincters. Fibrotic tracks at MR appear as bands of homogenous low signal intensity at T2W1 (black arrow in a). After the administration of gadolium, enhancement is homogenous throughout the fibrotic track (white arrow on b). FSE fat spin echo, SPGR spoiled gradient recalled echo. (Adapted from Sun MR, Smith MP, Kane RA. Current techniques in imaging of fistula in ano: 3D endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI 2008;29:454–471, with permission)

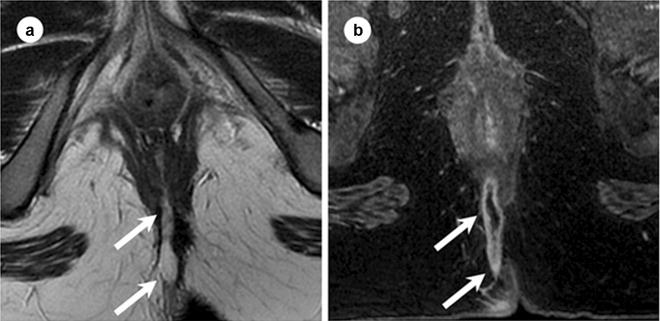

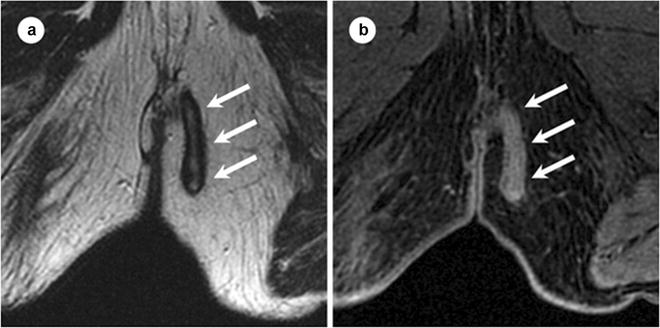

Fig. 19.3

Appearance of fluid-containing track at MR. Twenty-five-year-old female with posterior transsphincteric fistula. Axial T2 FSE (a) and postgadolinium T1W SPRG (b) images obtained at 1.5 T. Fluid-containing tracks show peripheral low signal intensity and linear central high signal intensity on T2WI (arrows in a). After the administration of intravenous gadolinium the track enhances peripherally but the fluid within the track lumen does not enhance (arrow in b). FSE fat spin echo, SPGR spoiled gradient recalled echo. (Adapted from Sun MR, Smith MP, Kane RA. Current techniques in imaging of fistula in ano: 3D endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI 2008;29:454–471, with permission)

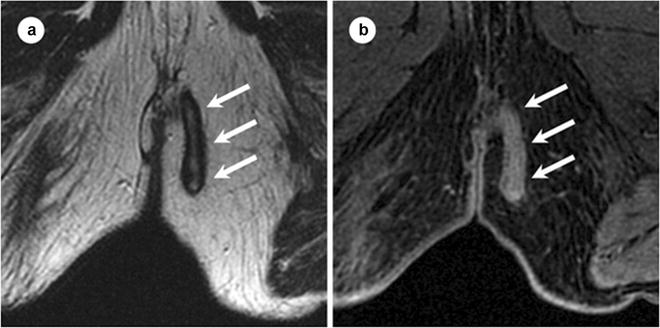

Fig. 19.4

Fistula track containing granulation tissue at MR. Seventy-seven-year-old male with transsphincteric fistula track containing granulation tissue. Axial T2 FSE (a) and axial T1W SPGR postgadolinium (b) images, obtained at 1.5 T. Granulation tissue within a fistula track appears similar to fluid within a track on T2WI, visible as a linear area of hyperintensity at T2WI (arrows in a). However, after the administration of intravenous gadolinium, granulation tissue enhances (arrows in b), while fluid within a track does not. FSE fast spin echo, SPGR spoiled gradient recalled echo. (Adapted from Sun MR, Smith MP, Kane RA. Current techniques in imaging of fistula in ano: 3D endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI 2008;29:454–471, with permission)

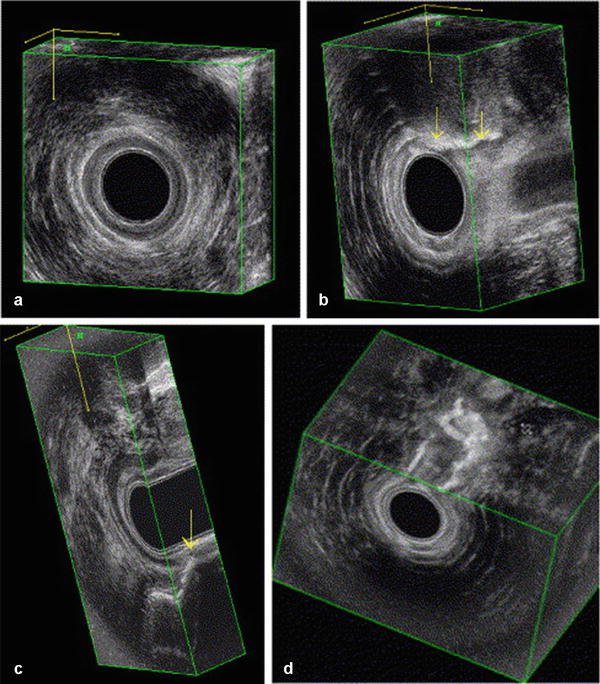

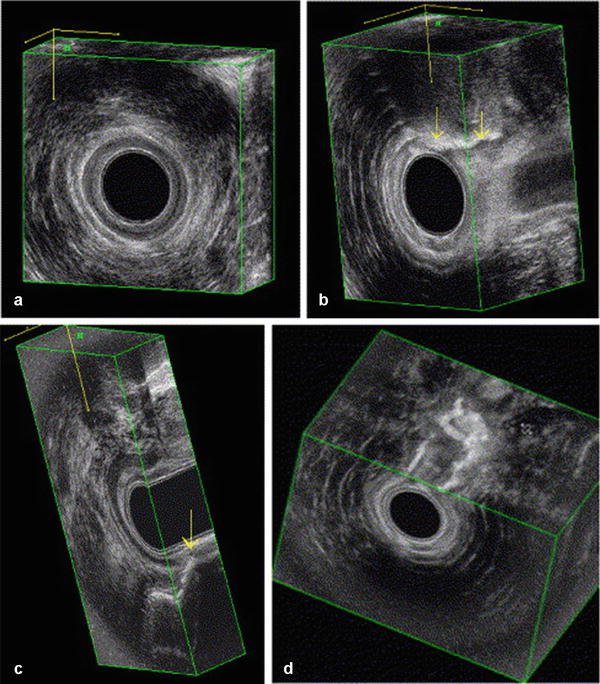

EUS of the anal canal was introduced in the 1980s [6, 7], and multiple studies have shown this technique to be accurate in defining fistula anatomy with greater ease and lower cost than MRI. Injection of peroxide into the fistula tract has been found to help accurately (95 %) delineate fistula tracts [8]. The tract will become hyper-echoic on ultrasound with this technique. Accuracy may be improved further by using the 3D EUS (Fig. 19.5). EUS is less accurate in detecting disease extending into the pelvis or ischiorectal fossa [9]. Crohn’s patients especially are less likely to tolerate the endoanal probe due to pain or the presence of stricture and this may limit the usefulness of EUS. The accuracy rate of EUS remains, in part, operator-dependent [10]. Multiple studies comparing EUS with MRI provide no clear consensus regarding superiority. Schwartz prospectively demonstrated equivalent accuracy between MRI, EUS, and EUA (87 %, 91 %, and 91 %, respectively) for determining fistula anatomy in Crohn’s disease patients. Combining MRI and EUS was noted to have a near 100 % accuracy rate for the detection and delineation of fistula tracts [11]. Sahni et al. found MRI to be superior to EUS with regard to specificity and sensitivity (97 % and 96 % vs. 92 % and 85 %, respectively) [12]. Selective use of MRI and EUS in conjunction with EUA is probably the best approach.

Fig. 19.5

Anal endosonography. Normal anatomy of the anal sphincter and puborectal muscle in 3D imaging: (a) frontal view of puborectal muscle (PR); (b) frontal view of the anal sphincters; (c) lateral view; and (d) coronal view. SM submucosa, IAS internal anal sphincter, EAS external anal sphincter. (Adapted from Felt-Bersma RJF. Endoanal ultrasound in perianal fistulas and abscesses. Digestive and Liver Disease 2006;38(8):537–543)

Medical Therapy

Once a diagnosis of Crohn’s fistula is made, it is important to have a treatment strategy planned. Crohn’s fistulas are often very complex, and the initial treatment modality should always be with medical therapy combined with drainage if necessary. Medical therapy may include appropriate antibiotics, immunosuppressive agents, or biologic agents. There is no role for corticosteroids in the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease.

Ciprofloxacin and Metronidazole

Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole have a role in the treatment of Crohn’s perianal fistulas. West prospectively compared ciprofloxacin in conjunction with infliximab vs. infliximab alone, and found that the response rate (50 % reduction in the number of draining fistulas) was 8 of 11 (73 %) in the combination therapy group vs. 5 of 13 (39 %) with infliximab alone [13]. However, this difference was not significant due to the small number of patients in the groups. Bernstein found that, in a series of 21 patients treated with metronidazole 20 mg/kg/day for 6–8 weeks, all patients noticed less discomfort, and 56 % had complete healing. However, the fistulas recurred in 75 % of patients on stopping the drug [14] and severe side effects included nausea and peripheral neuropathy. A small randomized, double blinded, placebo-controlled pilot trial at the Mayo clinic showed that remission and response occurred more frequently (but not significantly) in patients treated with ciprofloxacin [15]. The use of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole remains widespread for the treatment of this disease, despite the lack of conclusive evidence of their benefit.

Immunosuppressants

6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) and Azathioprine (AZT) have been used in the treatment of intestinal Crohn’s disease for many years. However, there have been no randomized controlled trials testing their efficacy in the treatment of perianal fistulas as a primary endpoint. Several reports have shown improvement or complete healing in up to 70 % of patients [16–19]. Ochsenkühn et al. combined azathioprine, 6-MP, and infliximab in patients with Crohn’s fistulas refractory to conventional management [20]. The 14 patients with perianal fistulas received 3–4 infusions of infliximab followed by long-term therapy with 6-MP and azathioprine. Complete closure of the fistula occurred in 13 patients for more than 6 months. They concluded that 6-MP and azathioprine may prolong the fistula closure achieved with infliximab.

TNFα Inhibitors: Biologics

Monoclonal antibody therapy against T cells has become the mainstay in medical treatment of perianal Crohn’s fistulas. Infliximab is a monoclonal antibody with mouse origin against TNFα which was initially approved for the treatment of intestinal Crohn’s disease in 1998 [21]. Infliximab is administered intravenously typically at 6–8 week intervals. The first randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s fistulas was done in 1999 by Present and associates [22]. This study included 94 patients with both intra-abdominal and perianal fistulas. At a dose of 5 mg/kg, there was a complete response with fistula closure in 55 % of the patients treated with infliximab vs. 13 % of patients receiving placebo. The most frequent adverse events occurring were headache, abscess, upper respiratory infection, and fatigue.

Adalimumab is a human-derived monoclonal antibody against TNFα. The CHOICE trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of adalimumab in patients who had failed to respond or lost response to infliximab therapy in 673 patients with Crohn’s fistula [23]. Approximately 40 % of these patients demonstrated healing of their fistulas by their last follow-up visit (ranging from 4 to 36 weeks). They concluded that adalimumab was an effective treatment for patients who failed therapy with infliximab.

This illustrates the largest problem with trials evaluating medical therapy. The usual follow-up in the study is less than 6 months. Typical follow-up for surgical treatment is greater than a year. This is even too short since fistula recurrence happens up to 5–10 years later. Short follow-up has limited our knowledge regarding medical treatment of fistulas. The true value of medical treatment may be reduction of active Crohn’s disease in the rectum and anal canal to allow definitive closure of the internal opening of the anal fistula.

Certolizumab pegol is a monoclonal antibody against TNFα combined with polyethylene glycol to prolong its half-life, allowing the drug to be administered monthly. PRECiSE 2, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial, evaluated the response to certolizumab pegol in 668 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s. This trial showed certolizumab to be effective in inducing a clinical response in 58 of 100 patients with anal fistulas. After 6 weeks, additional analysis was done separately on those patients with draining fistula. These patients were randomized to either maintenance therapy with certolizumab or placebo. A significantly greater number of patients maintained a 100 % fistula closure in the maintenance vs. placebo group (36 % vs. 17 %). The authors concluded that continuous treatment with certolizumab improves outcomes when compared with placebo [24].

Biologic agents are significantly more expensive and have some serious side effects including abscess formation and upper respiratory infections. Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that this group of drugs is more efficacious than antibiotics or immunosuppressants. The 2011 London Position Statement of the World Congress of Gastroenterology provided guidelines for the use of biologic agents in Crohn’s disease. Biologic agents are recommended for the treatment of complex fistulas. Infliximab should be regarded as the first line biologic agent for fistulizing Crohn’s at this time. All abscesses must be drained prior to initiation of a biologic agent as this can result in worsening perianal sepsis [25]. Adalimumab and certolizumab pegol may be reserved for treatment failures with infliximab.

Surgical Management

If optimum medical therapy fails, the patients may require more definitive surgical management of their disease. The first step in surgical management is to manage and treat perianal sepsis. Abscesses should be appropriately and thoroughly drained. A non-cutting seton using an inert material such as a silastic vessel loop may be placed for continued drainage and to mark the fistula for future surgical procedures. Appropriate antibiotics and medical therapy to control any active Crohn’s disease should be initiated. With appropriate drainage and control of perianal sepsis, fistulas may heal without any further surgical treatment, though the recurrence rates are high. Setons are generally effective in helping to control perianal sepsis but may be associated with recurrence after removal in up to 31 % of patients [26].

There are multiple other techniques for treating fistulas if simple drainage and medical management fails. Choosing the optimal surgical management requires consideration of the type of fistula involved. A proposed treatment algorithm is shown in Fig. 19.6. A low intersphincteric fistula may be treated with fistulotomy or fistulectomy. Excision of the tract leads to larger surgical wounds, and therefore fistulotomy of the superficial fibers of distal internal sphincter is preferred in most circumstances.

Fig. 19.6

Treatment algorithm for Crohn’s perianal fistula

High transsphincteric fistula tracts are best treated with the ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) technique or rectal wall advancement flaps, as the incidence of minor incontinence is less. Suprasphincteric fistulas start out as an intersphincteric abscess with a cephalad extension which then drains through the rectal outer wall and levator ani into the ischiorectal fossa and then to the buttock skin. Unroofing or drainage of the tract lateral to the external sphincter should be performed, and the remaining intersphincteric tract can be incised from the dentate line to the upper extent of the fistula. Setons are not recommended for suprasphincteric fistulas. Final closure with a sliding flap or proximal diversion may be required.

Extrasphincteric fistulas in Crohn’s disease are most often the result of a connection with intra-abdominal intestine. In this case, fistulotomy will not definitively treat the disease. Resection of the diseased portion of intestine is the only effective manner to bring about healing and eliminate recurrences of these fistulas.

Fistulotomy and Fistulectomy

The first step in performing a short fistulotomy for the low intersphincteric fistula is to identify the external opening. A probe is then placed through the opening and into the tract in order to try to identify the internal opening within the anal canal and document the amount of muscle encircled by the fistula. Once the probe is in place, the tissue overlying the probe may be divided using a scalpel blade or the cutting current of a cautery device. No external sphincter should be divided. If a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is suspected but not confirmed, curettings from the tract may be sent at this time.

If fistulectomy is chosen, the external opening is located and a stay suture is placed. The tissue around the fistula may be injected with local anesthetic and epinephrine to minimize bleeding. The skin surrounding the external opening is then divided. Scissors are used to core out the tissue surrounding the fibrous tract while the stay suture is retracted downwards. If the tract penetrates the external anal sphincter low, the muscle may be divided; however, if the tract is high or the patient already has other risk factors for incontinence, dissection should proceed in a meticulous fashion, coring out the track from the muscle and leaving most of the external anal sphincter intact. The defect may then be allowed to heal by secondary intention or may be closed with a suture or an advancement flap. The internal opening should be closed with figure of eight closure.

Fistulotomy or fistulectomy is not appropriate in females with anterior fistulas as the risk of incontinence is very high. Patients with a history of obstetric injury should not undergo either of these procedures. High transsphincteric or suprasphincteric fistulas involve a large portion of the external sphincter. Cutting through the sphincters at this level is associated with high rates of total incontinence. Preexisting scar in the rectovaginal septum which is involved by Crohn’s fistula may be injured and result in rectovaginal fistula (RVF) after fistulotomy or fistulectomy.

Postoperative care after fistulotomy or fistulectomy includes appropriate analgesia, tub baths with the water stream hitting the perineum at least three times a day, stool softeners as needed, and frequent follow-up visits. Packing the wound is not necessary. Marsupialization of the edges of the wound rarely lasts and there is very little difference from closure by delayed secondary intention. Some degree of leakage or lack of control may occur, and 90 % of cases will spontaneously resolve. Other postoperative complications include urinary retention, bleeding, pain, pruritis, and poor wound healing due to active Crohn’s. Anal stenosis from chronic inflammation may also occur as a late postoperative complication.

Flaps

Coverage of the internal opening with an advancement flap of the rectal wall may be considered for the treatment of anterior low rectal Crohn’s fistulas in patients where fistulotomy is not an option. Prior to this procedure any perianal abscess, sepsis, or active intestinal or perianal Crohn’s disease must be controlled. Although these flaps are often referred to as endorectal mucosal advancement flaps, various layers of tissue may be used including mucosal, partial thickness rectal, full thickness rectal, or perianal skin. Transanal advancement flaps close the internal opening and leave the external sphincter intact, thus they are associated with a lower risk of incontinence and recurrence. A broad-based U flap is raised with the apex starting approximately 5–10 mm below the internal opening and 10–15 mm in width on either side of the opening (Fig. 19.7a). The flap is raised, usually including mucosa and submucosa in the distal portion of the flap, and either partial or full thickness circular rectal wall muscle fibers (Fig. 19.7b). The length of the flap need only be enough to provide a tension-free closure after excising the fistula opening in the flap. The tract opening in the muscle and surrounding tissue is cored out and closed with interrupted absorbable monofilament sutures (Fig. 19.7c). The flap is secured over the top of the internal opening with interrupted absorbable braided sutures (Fig. 19.6d). The external opening is left open and curetted or drained with a mushroom tip catheter. In patients with low fistulas in the setting of long-standing perianal sepsis or anal stenosis, endorectal advancement flaps are not typically successful. In these cases, an anocutaneous advancement flap may be performed. Full thickness 2 × 2 cm diamond of perianal skin and subcutaneous fat is elevated adjacent to the fistula internal opening, ensuring there is a broad base with good vascular supply at its lateral aspect. The internal opening and surrounding tissue is once again excised with a vertically directed elipse and the tract closed. The skin flap is advanced into the anal canal and sutured over the internal opening with absorbable braided suture. The skin defect is then closed primarily resulting in a linear suture line with the appearance of a “kite tail” extending from the anal canal (Fig. 19.8).

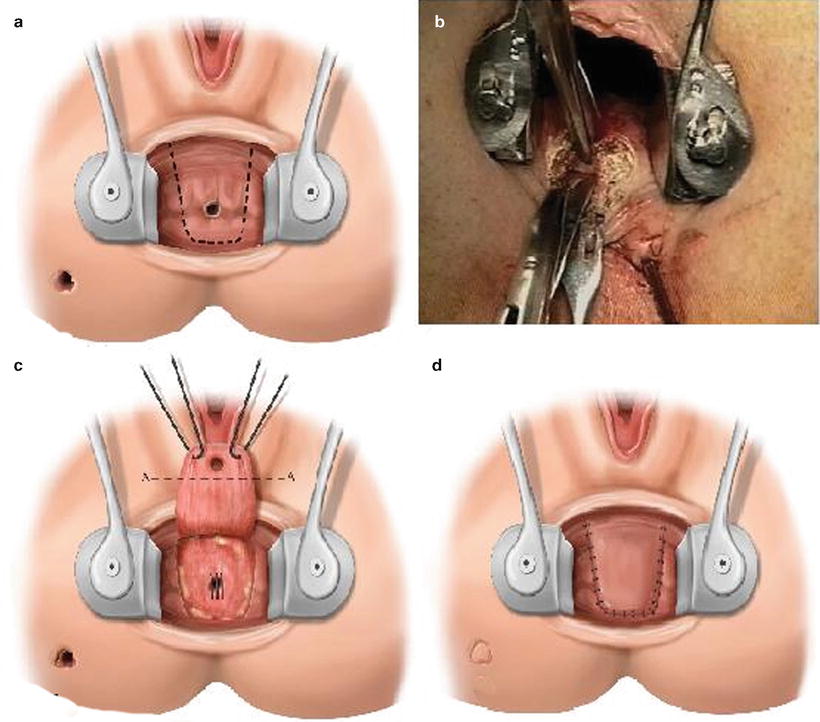

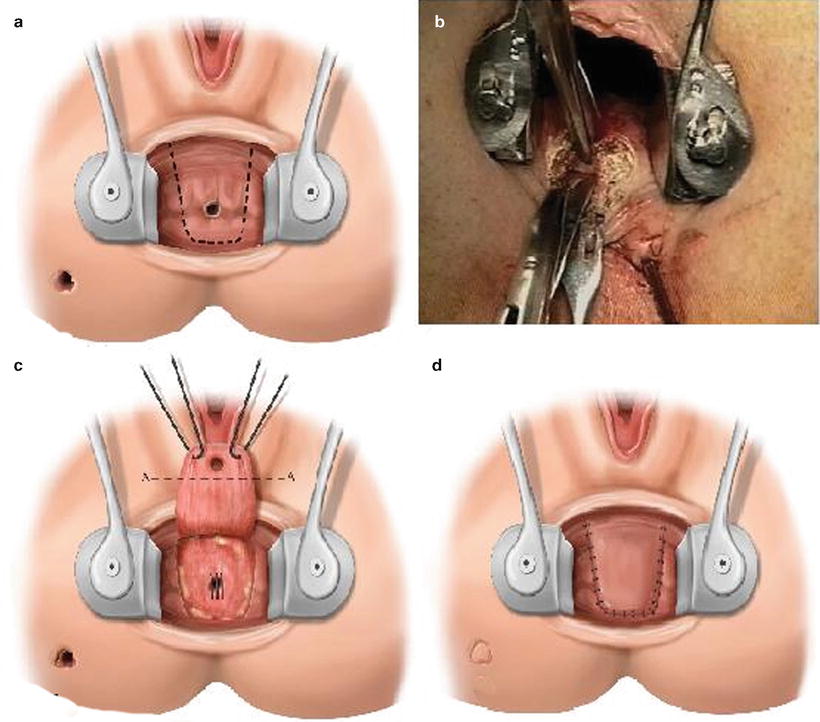

Fig. 19.7

(a) Line of incision for a broad-based U endorectal advancement flap (schematic), (b) developing the flap, in this case in the intersphincteric plane, raising a full thickness endorectal advancement flap, (c) fully mobilized flap retracted using two holding sutures. Internal opening excised along line A-A. Internal opening defect in the sphincter is closed with interrupted sutures (schematic), (d) sutured endorectal advancement flap (schematic). (Adapted from Wexner SD, Fleshman JW. Colon and rectal surgery: Anorectal operations 2012;44–46, with permission)

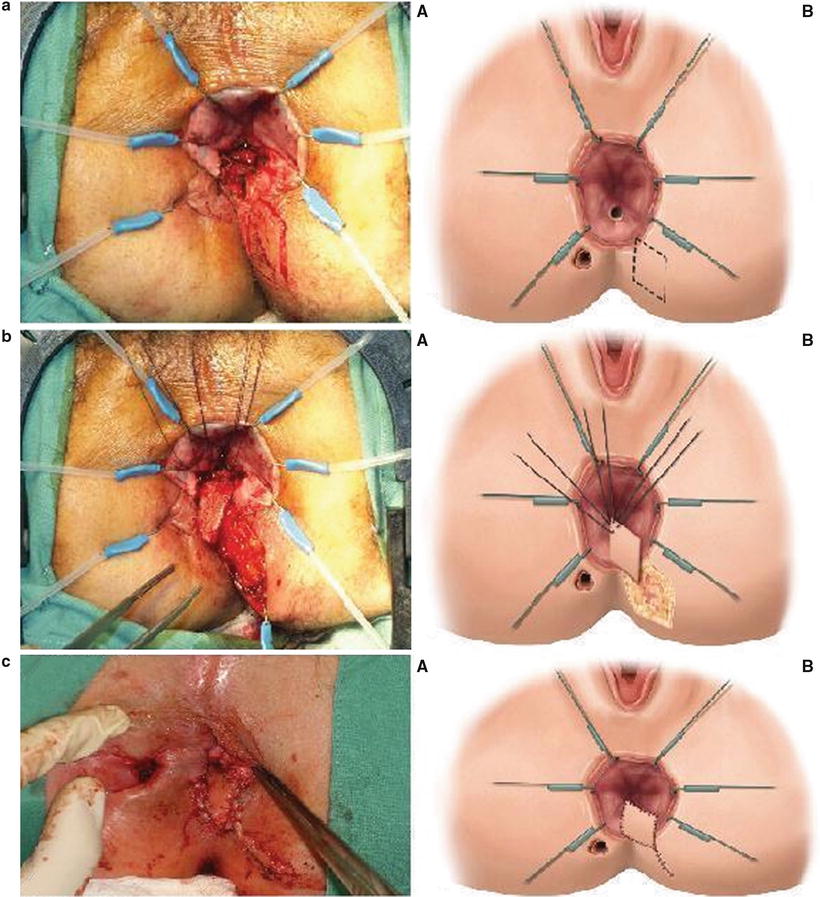

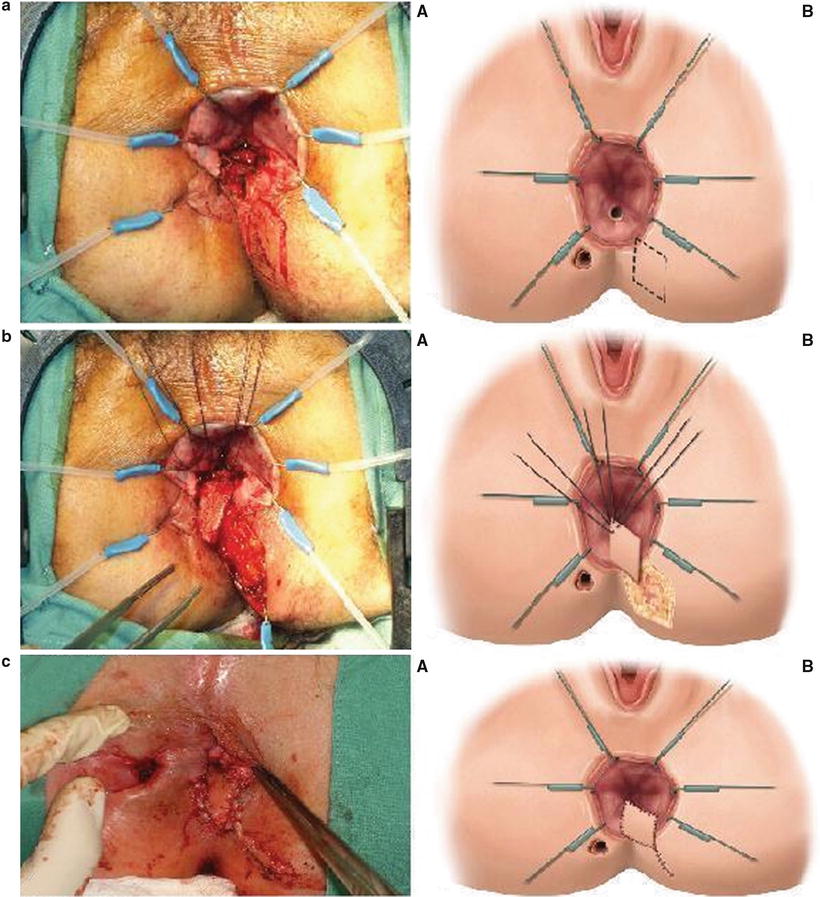

Fig. 19.8

(a) Incision for diamond-shaped anocutaneous advancement flap: (A) actual view and (B) schematic; (b) flap being advanced to cover the internal opening: (A) actual view and (B) schematic; (c) sutured anocutaneous advancement flap: (A) actual view and (B) schematic. (Adapted from Wexner SD, Fleshman JW. Colon and Rectal Surgery: Anorectal Operations: 2012:47–48, with permission)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree