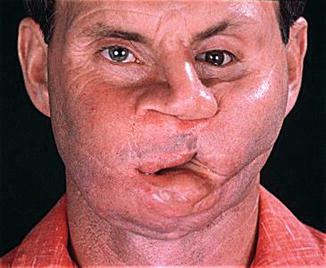

Fig. 18.1

Neurofibromatosis type 1, unsightly but incurable. An example of palliation in a benign condition

18.6.2.2 Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia occurs when normal bone is replaced with fibrous bone tissue. This results in abnormal growth or swelling of bone. Fibrous dysplasia can occur in any part of the skeleton but the bones of the skull, thigh, shin, ribs, upper arm and pelvis are most commonly affected and there is no known cure. Fibrous dysplasia is not malignant.

Most lesions in the head and neck region are monostotic that is involving one or adjacent bones. When the lesions are identified early and are small enough to be excised in their entirety, the condition can be cured. However, when allowed to grow extensively throughout the craniofacial skeleton, the manifestations can be gross affecting the airway, eyes and calvarium (Fig. 18.2). It is at this stage that management is long term and surgical intervention palliative.

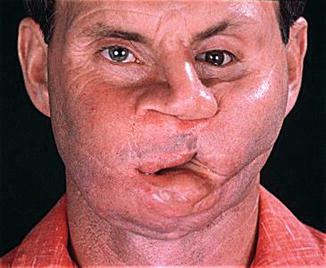

Fig. 18.2

Fibrous dysplasia, extending widely throughout the facial skeleton. The disease recurred relentlessly throughout this woman’s life

18.6.3 Other Incurable Conditions Requiring Palliation in the Broad Sense

18.6.3.1 Post-trauma

The all too common panfacial fracture and the unfortunate increase in gunshot wounds of the head and face result, in spite of high-quality modern reconstructive techniques, in clinical situations requiring palliative surgery in the broad sense of the term. Permanent change of appearance, ever-increasing restriction of jaw movement, progressive premature loss of dentition and ongoing care of damaged eyes and orbits present continuing palliative challenges to surgeons and their teams (Fig. 18.3).

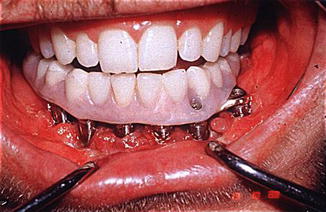

Fig. 18.3

Long-term follow-up of a devastating gunshot wound

18.6.3.2 Congenital Deformities

There are now an increasing number of patients with severe deformities who because of advanced health-care systems can lead relatively full lives but are in need of continuing monitoring with a view of surgical and other palliative measures as the disease process continues to manifest itself with age. An example of such conditions is the craniosynostosis syndromes of Crouzon and Apert. Even after full protocol management severe symptoms such as eye exposure, airway obstruction and loss of dentition may occur with age requiring surgical intervention for palliation (Fig. 18.4).

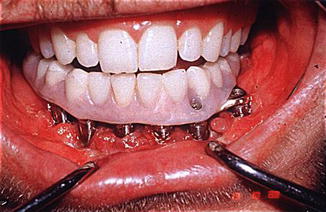

Fig. 18.4

Loss of dentition requiring osseo-integrated dental reconstruction as part of the palliative package

18.6.3.3 Some Degenerations

Other disease processes lend themselves to be considered in this context. Degenerations where bone and/or soft tissue withers and/or disappears over time such as Romberg’s hemifacial atrophy or hypertrophy and aberrant growth of Proteus syndrome (elephant man syndrome) (Fig. 18.5a–c).

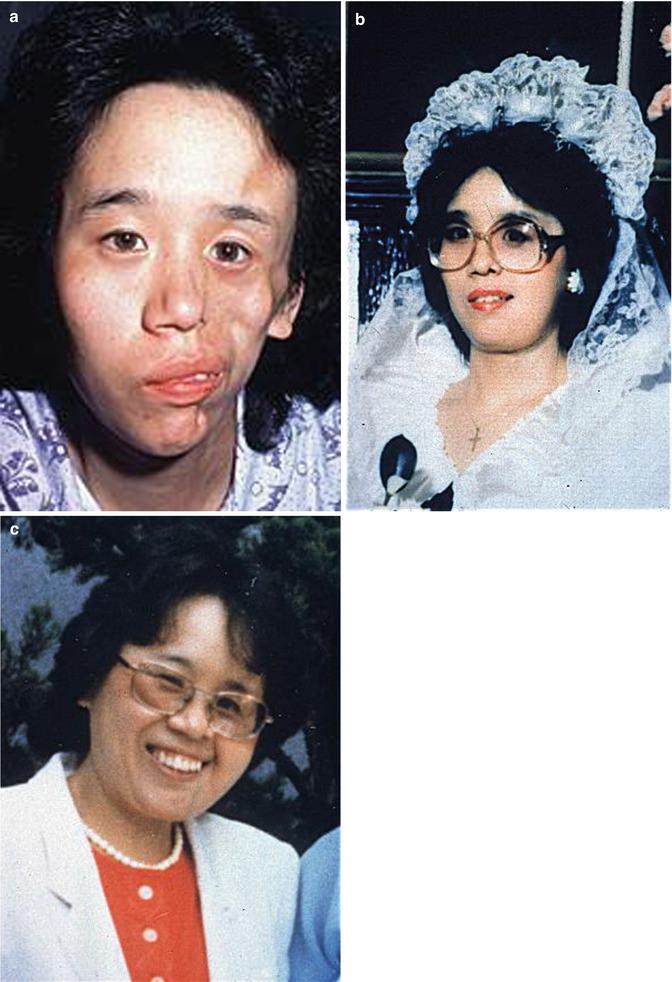

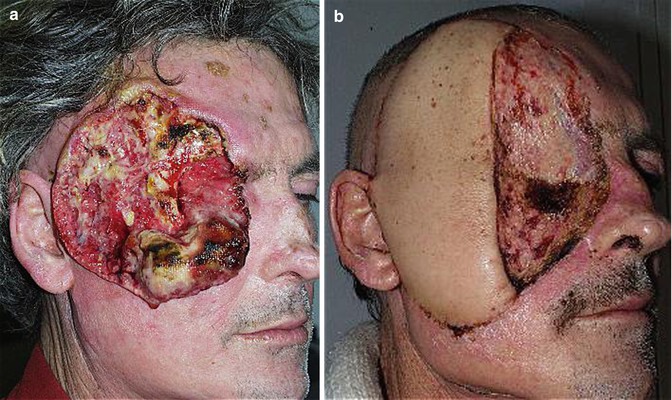

Fig. 18.5

(a–c) Romberg’s hemifacial atrophy

18.7 Planning

18.7.1 The Team, the Treatment Protocol and the Outcome Measures

The necessity of the team approach and systems-based practice is widely recognised in the literature if not so widely practiced in reality [5–9].

Those patients with cancer require a continuum of management as the disease progresses, and it is not always evident to the patient or treating specialists whether treatment is still being aimed at cure or for the relief of symptoms. If surgery is to be used for the dedicated purpose of relief of symptoms, this will need to be made clear. The decision processes necessary during the progress through incurable disease to death are best managed by a team so that the protocols can be adjusted, and all modalities of care necessary to palliate the patient are introduced in a timely and effective manner.

Some palliative measures may need to be introduced at a time when there is still a hope of cure and such therapies are in place, for example, airway protection, measures to reduce disfigurement and covering a potentially vulnerable vessel.

Measuring outcomes is intimately bound up with delivery of the service by a multidisciplinary team as surgeons and patients expectations may not match and the differences may not be communicated. The role of social worker, palliative nurses and others on the team is crucial in bridging this gap. Meaningful data on the outcomes of palliative surgery are understandably difficult to come by; however, it is clear that there is little time between decision to palliate and time of death placing an emphasis on surgeons not to make the surgical intervention more burdensome than the disease. Many of the problems encountered with meaningful outcome measures in this difficult area of practice are well described by Shuman and colleagues [10, 11]. These authors and others fully acknowledge that further research in the experience of managing patients with terminal head and neck malignancy is greatly needed.

There is little or no literature directed to the broader concept of palliation as applied to the nonfatal but incurable diseases mentioned previously.

18.8 Surgical Techniques for Palliation of Craniomaxillary Disease

At the point when attempts to cure give way to palliation, it is quality-of-life issues that become the patients and hence the treating team’s primary concern. The following symptoms are the most common in those patients approaching death with their incurable disease.

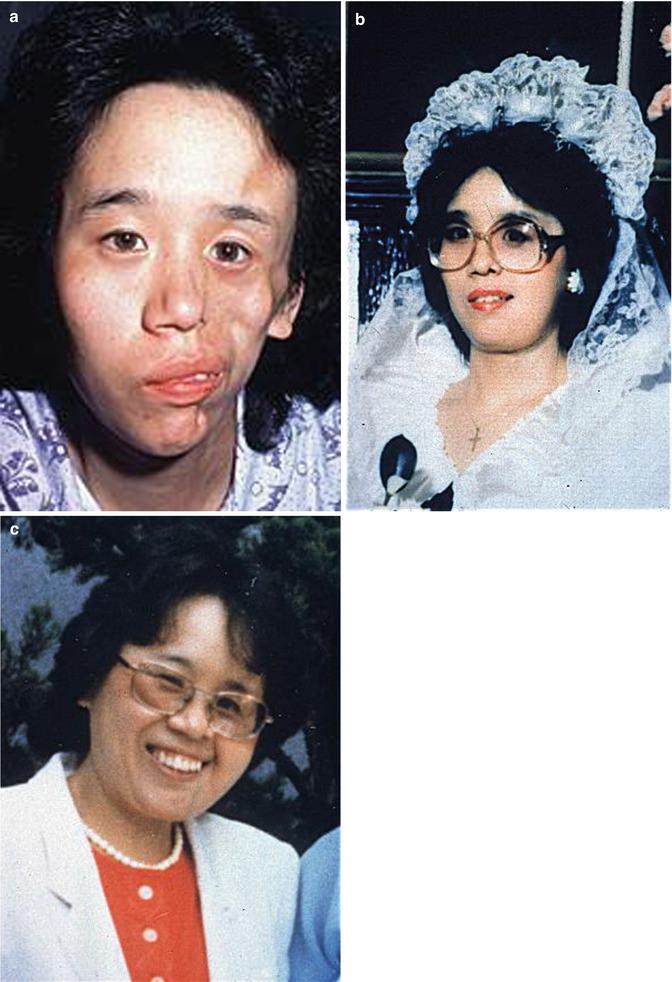

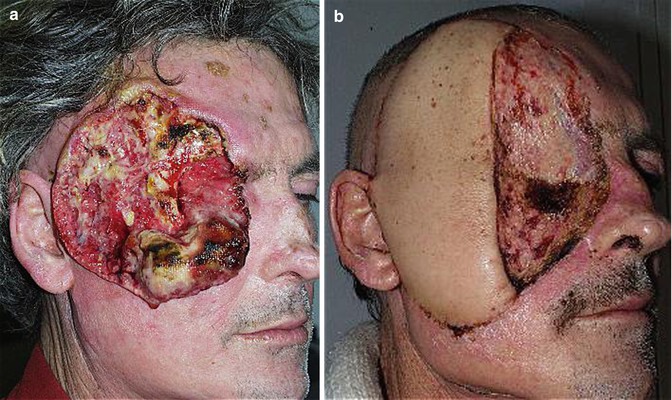

Pain from head and neck cancer can be caused by direct stimulation of nerve endings, by ulceration and infection producing and open wound, by compression and invasion of sensory nerves (Fig. 18.6a, b) and by invasion of bone.

Fig. 18.6

(a, b) A massive painful fungating tumour (a) palliated by excision and flap coverage (b)

The referred pain from the tonsillar fossa tumour to the ear is an example of direct stimulation.

Ulceration and infection in the oral cavity produces pain that is exacerbated by irritant factors during eating and swallowing. Skin ulceration, for example, on the scalp, is often painful to debride, clean and dress.

Nerve invasion can result in tumour travelling through the cranial base foraminae to the Gasserian ganglion and beyond. Cranial nerves V and IX are most frequently involved in this manner.

Bone pain may be exacerbated by a pathological fracture, e.g., of the mandible, or associated with nerve pain as the tumour invades the skull.

The management of pain rarely falls in the realm of surgery and is most often managed by specific pain teams. The techniques of nerve blocks may be very helpful in this region. Irrespective of who is palliating these patients, it is the author’s experience that the surgeon should maintain close contact with the patient who almost invariably considers this as a significant support.

It is worth revisiting the difficult situation of “salvage surgery” when the aim of the surgeon may be ambivalent, there being still some hope of cure, but emphasis is also on preventing pain caused by local recurrence. The poor outcomes in terms of complications and function place the emphasis on the surgeon to carefully consider the options [12]. A potentially short survival time together with a high complication rate from complex surgery is not a good combination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree