Fascial slings remain a successful and durable option for treatment of female stress urinary incontinence (SUI). With limited risk of disease transmission, extrusion, or complications associated with mesh, use of autologous fascia is an attractive option, particularly for complex reconstructive cases. With generally robust outcomes, pubovaginal slings also continue to be a viable option for treatment of primary SUI after appropriate patient counseling regarding risks of bladder outlet obstruction and de novo urgency symptoms.

- •

Autologous fascial pubovaginal slings remain a durable therapy for female stress urinary incontinence.

- •

Fasical slings are particularly indicated for cases of complex intrinsic sphincteric deficiency, concomitant urethral reconstruction, and recurrent incontinence.

- •

Counseling regarding risks of de novo voiding dysfunction and obstruction is critical to insure outcomes match patient expectations.

Introduction

Contemporary urologists have witnessed immense advances in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in the past decade. A plethora of innovative technologies have emerged as a result of increased understanding of the pathophysiology of SUI, with the application of midurethral slings (MUSs) revolutionizing treatment of SUI. Relative ease of the MUS procedure has allowed practitioners not formerly familiar with the intricacies of pubovaginal slings (PVSs) to successfully treat patients with SUI. However, this expansion of technology has been accompanied by increasing incidence of complications related to the use of mesh in women treated for SUI, including vaginal extrusions, erosions into the urinary tract, chronic pain, and sexual dysfunction. Mesh MUSs are not appropriate for every indication, and traditional methods such as the autologous fascial PVS remain the gold standard of treatment based on longevity of results and adaptability of the procedure to a vast array of circumstances. This article reviews the current indications for autologous fascial PVSs and data regarding sling outcomes, and details the operative technique for fascial harvest and sling placement.

Indications

The ideal sling would be effective, durable, straightforward to insert, minimally invasive, associated with low morbidity, affordable, and applicable to all types of SUI. Although it is becoming rapidly evident that MUS technologies may possess many of these model sling traits, treatment of all types of SUI is not among the attributes. Numerous criteria should be measured when creating an algorithm for sling placement. Specific clinical scenarios to consider that may be best served by an autologous fascial PVS include women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency and a fixed urethra, simultaneous prolapse repair, concomitant urethral surgery such as diverticulectomy or fistula repair, and urethral reconstruction secondary to trauma. In all of these high-risk circumstances, use of autologous fascia is preferable over the synthetic MUS tapes. Although significant controversy continues regarding treatment of MUS failures, the PVS remains a primary option for failed alternative incontinence procedures. Autologous slings may also serve as an excellent alternative to bladder neck closure in populations with supravesical diversion, such as suprapubic catheter or bladder augmentation with continent catheterizable channels.

Based on panel consensus, the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines for SUI indicate that synthetic sling surgery is contraindicated in patients with concurrent urethrovaginal fistula, urethral erosion, intraoperative urethral injury, or urethral diverticulum. Although sparse standardized data exist specifically on these special circumstances, panel members recommend preferential use of autologous fascial or other biologic materials in these circumstances.

Although a variety of autologous tissues have been examined through the years, only rectus fascia and fascia lata have substantial evidence to support current consideration. Both autografts by definition have proven noncarcinogenic and nonallergenic, and fascia has been proven a durable medium to potentiate long-term efficacy. Most postoperative complications with autologous fascial harvest are related to abdominal hernia and wound infection.

In addition to autografts, wide arrays of allografts and xenografts have been analyzed for treatment of SUI and pelvic organ prolapse. Although many of these materials have proven to be biocompatible and certainly decrease the morbidity of autologous fascial harvest, long-term efficacy rates may eventually preclude preferential use of these materials, with sparse data available to guide practitioner choice.

Indications

The ideal sling would be effective, durable, straightforward to insert, minimally invasive, associated with low morbidity, affordable, and applicable to all types of SUI. Although it is becoming rapidly evident that MUS technologies may possess many of these model sling traits, treatment of all types of SUI is not among the attributes. Numerous criteria should be measured when creating an algorithm for sling placement. Specific clinical scenarios to consider that may be best served by an autologous fascial PVS include women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency and a fixed urethra, simultaneous prolapse repair, concomitant urethral surgery such as diverticulectomy or fistula repair, and urethral reconstruction secondary to trauma. In all of these high-risk circumstances, use of autologous fascia is preferable over the synthetic MUS tapes. Although significant controversy continues regarding treatment of MUS failures, the PVS remains a primary option for failed alternative incontinence procedures. Autologous slings may also serve as an excellent alternative to bladder neck closure in populations with supravesical diversion, such as suprapubic catheter or bladder augmentation with continent catheterizable channels.

Based on panel consensus, the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines for SUI indicate that synthetic sling surgery is contraindicated in patients with concurrent urethrovaginal fistula, urethral erosion, intraoperative urethral injury, or urethral diverticulum. Although sparse standardized data exist specifically on these special circumstances, panel members recommend preferential use of autologous fascial or other biologic materials in these circumstances.

Although a variety of autologous tissues have been examined through the years, only rectus fascia and fascia lata have substantial evidence to support current consideration. Both autografts by definition have proven noncarcinogenic and nonallergenic, and fascia has been proven a durable medium to potentiate long-term efficacy. Most postoperative complications with autologous fascial harvest are related to abdominal hernia and wound infection.

In addition to autografts, wide arrays of allografts and xenografts have been analyzed for treatment of SUI and pelvic organ prolapse. Although many of these materials have proven to be biocompatible and certainly decrease the morbidity of autologous fascial harvest, long-term efficacy rates may eventually preclude preferential use of these materials, with sparse data available to guide practitioner choice.

Operative technique

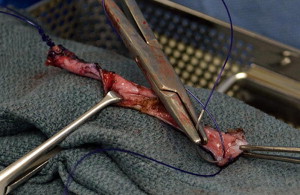

Current AUA guidelines for perioperative antimicrobial treatment include a first- or second-generation cephalosporin or an aminoglycoside with the addition of metronidazole or clindamycin. Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis should be used per AUA guidelines; however, for most patients, pneumatic compression devices are sufficient. The patient is positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position, with care to not excessively elevate or hyperextend the legs. After appropriate skin preparation, a 16F balloon catheter is inserted into the bladder. Fascial harvest begins with a 6- to 8-cm transverse Pfannenstiel incision approximately 2 cm above the pubic symphysis. Dissection is carried down through subcutaneous tissue until rectus fascia is readily identified. It is important to clear enough adipose and connective tissue off the rectus fascia so as to allow a clean closure without overdissection and creation of a potential space that may allow seroma formation. Exposure of the fascia by an assistant with Richardson retractors is often sufficient for excellent visualization. Using a surgical marking pen, the fascial sling is marked out as an 8 to 10 cm × 2 cm strip approximately 2 to 3 cm above the pubis ( Fig. 1 ). Creating the harvest too close to the pubis will limit the capacity to dissect, and hinder adequate mobility for fascial closure. The fascia is then scored with electrocautery to outline the eventual harvest, because distortion is likely during the harvest ( Fig. 2 ). The fascial sling is raised from the rectus muscle and cut with electrocautery. Great care should be taken to not enter the underlying muscle or midline, because often patients have undergone prior operations and have substantial scar tissue in this area ( Fig. 3 ). Once the fascia is harvested, it is placed in normal saline on the back table and #1 polydioxanone sutures are secured on each end of the strip in a horizontal mattress fashion at right angles to the fiber direction. These sutures remain long for passage through the retropubic space ( Fig. 4 ). Fascial edges are raised with Allis clamps and undermined circumferentially with electrocautery to allow sufficient mobility for a tension-free closure ( Fig. 5 ). Fascia may then be approximated in a running fashion with #1 polydioxanone sutures. The wound is packed with saline or antibiotic-soaked sponges and attention is turned to the vaginal portion of the procedure.

For the vaginal dissection, exposure is first obtained with placement of a weighted vaginal speculum. Labial retraction may be required in some instances and achieved with either silk retraction sutures or a ring retractor. A semilunar inverted U incision is marked out on the anterior vaginal wall from the bladder neck, identified with gentle traction of the catheter to identify the balloon, to the mid urethra. The vesicovaginal space is hydrodistended with sterile saline to facilitate the dissection. The initial incision is created with a scalpel, and the avascular plane superficial to the pubocervical fascia is carefully dissected with Metzenbaum scissors with traction from an Allis clamp on the vaginal epithelium ( Fig. 6 ). Palpation of the depth of dissection is a critical aspect of the procedure, because a dissection too deep into detrusor fibers will result in not only bleeding but also potential entry into the urethral or bladder lumen. The proper plane on the vaginal wall has a characteristic shiny white appearance.

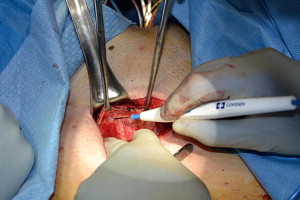

Dissection is then accomplished laterally toward the ipsilateral shoulder under the vaginal mucosa until the ischiopubic ramus is palpated ( Fig. 7 ). The concavity of the scissors should be maintained laterally to avoid damage to the urethra or bladder. Sufficient space is required to pass the sling, which can be approximated by a fingerbreadth. Once the pubis is palpated, the scissors are maintained in the superolateral direction toward the ipsilateral shoulder and the endopelvic fascia is pierced directly under the bone. Once the endopelvic fascia is opened, the retropubic space is entered bluntly with finger dissection and a sweeping motion cranially is used to free the bladder neck and urethral attachments behind the pubis. In complex cases with significant retropubic scarring, it may be preferable to leave the fascial incision open to directly palpate the tract from the abdominal incision and direct guidance with the vaginally placed finger for passage of the suture ligature needle. In reoperative cases, brisk bleeding is not uncommon once the endopelvic fascia is perforated, and is often best managed with direct pressure and expeditious passage of the sling. Ligature passing instruments, such as Stamey needles or Tonsil clamps, are used to pass from the suprapubic incision into the vaginal incision on either side of the bladder neck with direct finger guidance ( Fig. 8 ). After ensuring the bladder is empty, a finger is placed into the vaginal incision behind the pubis and the ligature passing instrument is inserted in a stab incision through the rectus fascia approximately 2 cm laterally from midline directly on the pubic bone. The ligature passing instrument is walked along the bone cranially and enters the retropubic space adjacent to bone. Once behind bone, the passer is angled toward the vagina and should be directly palpated and guided into the vaginal wound on the fingertip. Once the passer is visible in the vaginal wound, the procedure is repeated on the contralateral side.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree