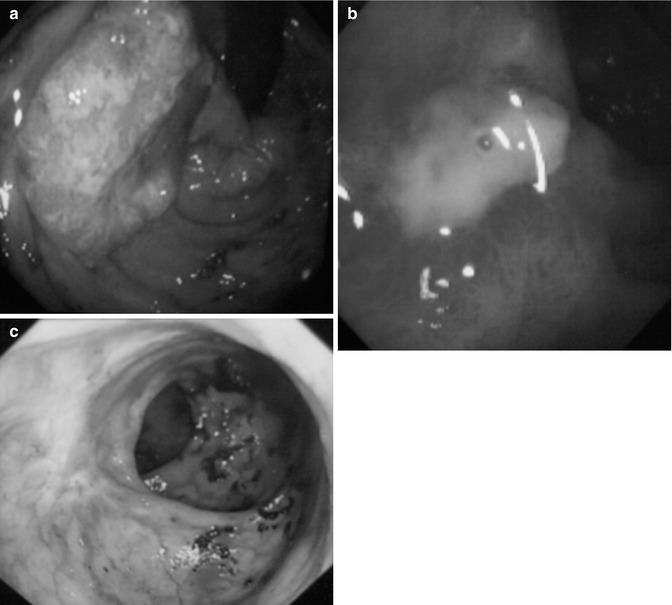

Fig. 8.1

(a) Pretreatment (day 0) T2N0M0; (b) Post treatment (day 14); (c) Post treatment (day 28) after 2 fractions, showing good response (good responder)

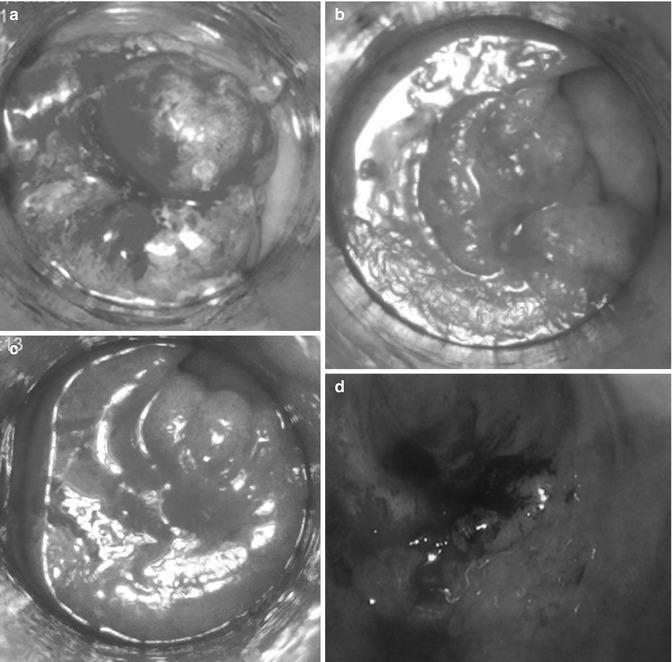

Fig. 8.2

(a) Malignant rectal cancer T3N1M0; (b) Post treatment ulcer; (c) Post treatment healed scar (10 years)

Investigations

Case selection is important for successful outcomes and initial staging is very important. All cases should be discussed at the colorectal MDT meeting. Complex cases should be discussed at the specialist early rectal cancer MDT, because the issues involved can be difficult. Patients should be inform about the consensus of opinion from the experts. However, the final management decision rests with the patient, therefore they should be well-informed. Help should be available to clarify matters and their decision must not be obtained under duress. Endoscopy with biopsy to establish histological diagnosis is mandatory. Histology should confirm the invasive malignancy and it is also important to exclude any adverse histopathologic prognostic features that may be a relative contraindication for local treatment. Poorly differentiate adenocarcinoma and the presences of lympho-vascular involvement are the two most important features. In some cases, the decision to treat or not to treat is complex, and enough time should be allowed to come to mutual agreement. All patients should have baseline high-resolution MRI [3], contrast enhanced CT scan of chest, abdomen and pelvis. Intra-anal ultrasound (EUS) if available is useful to differentiate early tumours T1 from T2 but it is important to understand that this distinction is not always clear-cut. A PET/ CT scan is not routinely done as part of initial investigations. If the tumour marker CEA is high at diagnosis, it is useful to monitor response and to detect recurrences during follow-up assessments.

Preparation of Patient

X-ray contact brachytherapy can be carried out as a day patient procedure. The patient stays on a low-residue diet for 3–5 days before treatment. On the day of treatment a micro-enema is given per rectum half an hour before treatment. This clears the bowel, which helps to identify the tumour margins accurately. The patient is generally treated in prone jack-knife position, which helps to open the rectal lumen (Fig. 8.3), but sometimes in lithotomy position can be useful for low posterior cancers. Techniques to inflate the rectum for better visualization of the tumour have been developed and will help for centres starting with this facility. Local anesthetic gel (Instillagel®) is applied around the anus to numb the area and ease any discomfort. In addition, glyceryl trinitrate (Rectogesic®) or a similar preparation can be applied to relax the muscles around the anus. This will help to ease the discomfort when inserting the rectal applicator.

Fig. 8.3

Treatment position for contact X-ray brachytherapy

Treatment Protocol

There are three sizes of rectal applicator, 30, 25 and 22 mm, and the choice depends on the size of the tumour. If the rectal cancer is less than 30 mm, the treatment can start with contact X-ray brachytherapy. For larger tumors, external beam chemoradiotherapy 45 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks (EBCRT) with capecitabine 825 mg/m2 is used initially to downsize the tumour. In elderly patients with compromise renal function the dose can be modified. For those who are not fit for chemotherapy, because of cardiac problems or poor renal function, short course radiotherapy (SCRT) 25 Gy in 5 fractions over 5 days can be used instead. However, there is evidence from the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group trial (01.04) that long course CRT will downsize and downstage the tumour much more effectively, with pCR 15 % vs. 1 % in favor of long course for more advanced T3 rectal cancers [4]. Even after short course and delay, the regression of tumour can be quite slow. A contact X-ray brachytherapy boost can follow EBCRT within 2–4 weeks to improve local control. A randomised trial called OPERA (Organ Preservation for opErable Rectal Adenocarcinoma) is being set up to evaluate this hypothesis. The dose of contact X-ray brachytherapy is usually 30 Gy per fraction in three fractions given every 2 weeks. Although the physical dose delivered is 30 Gy, the radiobiological effect (RBE) of orthovoltage low-energy X-rays is much higher at 1.4–1.6, so the equivalent dose effect (EQD) is increase to the dose range above 40 Gy per fraction. This dose is delivered in just over 1 min, where normally with external beam the equivalent radiation dose is delivered in 4–5 weeks. As a result of this dose intensity, the cancer-cell kill effect has a very steep slope. The dose of external beam radiotherapy 45 Gy and contact X-ray brachytherapy of 90 Gy, giving a total dose of 135 Gy delivered, however, this dose is radiobiologically equivalent to 160 Gy. This seems a very high dose but it has little effect on the normal surrounding tissues, as most of the dose is applied directly onto the surface of the tumour and not on the normal surrounding tissues beneath it. The tumour is shaved off layer by layer with each application of X-ray brachytherapy, until it regresses completely (Fig. 8.1).

Possible Side Effects

The side effects were reviewed on 100 patients, treated with the new Papillon RT 50 machine at Clatterbridge from 2009 to 2010. There were 69 males. The median age of patients was 72 years (range 33–99). Elderly and unfit patients had radical RT (n = 43), post-op (n = 39), pre-op (n = 5) and palliative (n = 13). The Papillon dose was 60 Gy in 2 fractions over 2 weeks (post-op) and the radical group had 90 Gy in three fractions over 4 weeks following EBCRT or SCRT 25 Gy in 5 fractions over 5 days. The main toxicity was bleeding, occurring in 26 % of patients. Fifteen patients had mild bleeding and five had G3 bleeding requiring Argon plasma coagulation. No patients needed blood transfusions or defunctioning stoma to control their bleeding. Two patients developed rectal pain following treatment. Both had very low-rectal tumors just above the dentate line. One needed immediate salvage surgery for residual tumour, the other patient’s symptoms settled with conservative treatment after 8 weeks. There were no fistulas or strictures caused by the new contact machine. There was no 30 days mortality related to contact radiotherapy [5].

Follow-Up

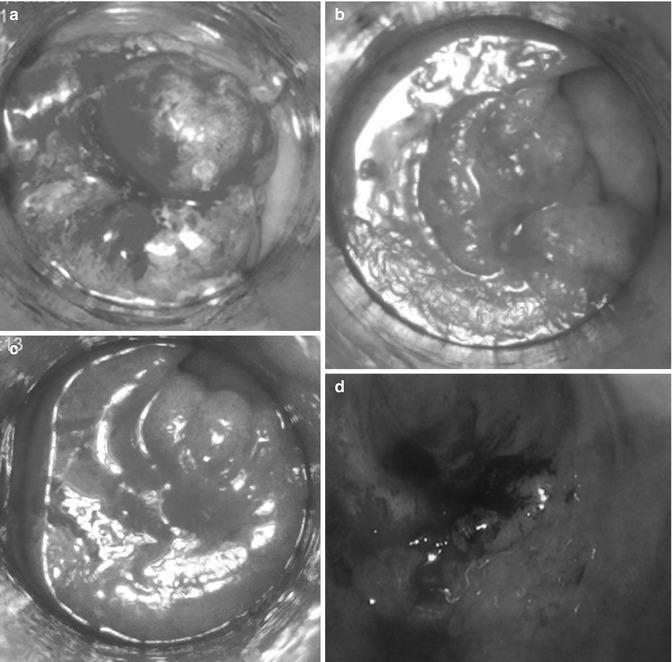

Patients who achieve a complete clinical response following contact X-ray brachytherapy are followed up similarly to those in the watch and wait group following chemoradiation [6]. As most of the recurrences are in the first 2 years, intensity of follow-up is concentrated around this time. One needs to be mindful of the extra anxiety caused to patients during this period and the extra cost of the investigations offered. Patients should be reviewed every 3 months in the first 2 years and 6 monthly up to 5 years. Digital rectal examination (DRE) and endoscopy is carried out as part of the examination during these visits. It is important that one or two experience observers review the patients regularly, as there could be some subtle mucosa changes that need to be observed closely without a biopsy. Experience centres advocating the ‘watch and wait policy’ advice not to biopsy these lesions, as the histology are difficult even for the most experience pathologists to interpret [6]. The area of biopsy may not be representative of the status of the tumour, as there could be a geographical miss. The ulceration caused by a deep biopsy may not heal, and there could be persistent pain and bleeding from this area. In addition, it makes the interpretation of mucosal changes difficult in the future. If persistent mucosal abnormality is causing concern, the whole area should be excised using transanal endoscopic mucosal resection (TEMS) to obtain an accurate histology, including full thickness of the muscle to assess the histology fully (Fig. 8.4) [7]. The majority (61 %) of mucosal abnormalities do not harbor invasive malignancy apart from low- to high-grade dysplasia, which does not require major surgical resection [8]. However, if there is suspicion of bulky residual disease either from MRI, endoscopy or digital examination, provided that the patient is fit and agreeable to surgery, immediate salvage surgery should be offered. High-resolution MRI scans should be carried out with diffusion weighting imaging (if available) every 3 months in the first 2 years and 6-monthly in the third year. CT scanning should be carried out at 6-monthly intervals in the first 3 years. The timing for these investigations is still not internationally agreed, and as more centres gain experience with the ‘watch and wait’ policy some consensus on follow-up policy can be agreed at the international meetings that are now held regularly every year. The risk of recurrence is low after 3 years but follow up should continue 6-monthly up to 5 years at least. Recurrences beyond 5 years are very rare, and if patients agree to longer term follow up and local healthcare systems permit this, they should be follow up for 10 years.

Fig. 8.4

(a) Pretreatment (day 0) 07/06/12; (b) Post treatment day 14 (20/06/12); (c) post treatment day 28 (05/07/12); (d) Possible recurrence 14 months later. Had TEMS (14/11/13) Histology –TVA with low grade dysplasia, no invasive malignancy

Evidence of Efficacy for Contact X-Ray Brachytherapy

Contact X-ray brachytherapy has been around for more than 80 years. Initial treatment was carried out in Berlin with a 50 kV machine made by Siemens. Chaoul treated more than 100 patients, many of them with unresectable rectal tumors. Primary healing occurred in 62 patients and 30 patients were cured at follow-up of 4–17 years [9]. In 1946, Lamarque and Gros from Montpellier laid down the guidelines for contact radiotherapy. They conducted a study of histological changes and observed early signs of cytoplasmic and nuclear degeneration a few hours after contact radiotherapy and increasing during the next few days. They showed that bowel epithelium can be destroyed by a single dose of 40 Gy but the regeneration was complete 1 month later. They reported on a series of 116 patients with rectal cancer treated by contact radiotherapy. Cure rates at 5 years even for advanced inoperable tumour were 20 % [10]. These were remarkable results, because in that era adenocarcinoma of the rectum was thought to be radioresistant. Papillon started the contact radiotherapy facility using a 50 kV Phillips machine in Lyon in the early 1950s. He reported on 312 patients with T1 rectal cancer treated by contact X-ray brachytherapy alone from 1951 to 1987 with a 5-year survival of 74 %. There were only 9 local recurrences and 7.7 % of cases died from cancer-related causes. The remaining non-cancerous deaths were related to advancing age with co-existing medical problems. For more advanced cases T2 or T3, Papillon used external beam radiotherapy, 39 Gy in 13 fractions over 17 days. This was followed by contact X-ray brachytherapy and iridium implant boost. This regime was used in 67 patients (median age 74 years) and they were followed up for more than 5 years. At 5 years the survival was 59.7 %. Of the 40 patients who were alive and well, 39 had normal anal function and only one had undergone APER for local failure. Among the 8 patients who died of cancer, 3 had distant metastases and 5 had pelvic failures. Eighteen patients (26.8 %) died from intercurrent disease due to poor general condition of patients [11]. Papillon observed a relationship between the size of tumour and the chance of cure. Five year survival rate was 80 % for lesions 3 cm or less and for larger tumours was only 61.5 %. The configuration of the tumour seems to have less prognostic significance than the size of the lesion. However, distant metastases occurred twice as frequently for ulcerative tumours. In 1980, Sischy from Highland Hospital in Rochester (New York) reported a series of successfully treated limited rectal carcinomas by contact radiotherapy in the USA. Of 74 patients treated for cure, only 4 had local failure. Seventy patients followed up for at least 18 months were alive and well and free of disease (94 %) [12]. Myerson and his colleagues from Washington University, St Louis, reported on 199 patients treated from 1980 to 1995. They found that the most important factors for local control (Multivariate analysis) were the use of external beam radiotherapy (P < 0.001), prior removal of macroscopic disease (P = 0.001) and mobility on palpation (P = 0.009). Endocavitary treatment was very well tolerated. Of 199 cases, 19 (9.5 %) had minor transitory tennesmus or bleed, managed conservatively. The only grade 3 or 4 morbidities occurred in those patients who needed salvage surgery for tumour recurrence. In the update of their series to 2004, they had 59 T1 lesions identified. Forty of these 59 cases underwent local excision of all macroscopic disease before radiation. With radiation all but 3 (who had a history of prior pelvic radiation for other malignancy) received a combination of external beam (usually 20 Gy in 5 fractions over 5 days) followed 6–8 weeks later by endocavitary radiotherapy. There were only 3 failures and only one (1.8 %) in the 56 who received external beam radiotherapy. The difference between this cohort and the experience reported from others using local excision without contact radiotherapy was highly significant (55/59 vs. 106/129 [P = 0.003]) [13]. Gerard reported on 101 patients with T1/T2 tumour treated with contact radiotherapy between 1977 and 1993. There were only 10 % local failures, with 83 % overall survival at 5 years [14]. He further reported on 63 patients with T2 and T3 tumour and a median age of 72 years treated between 1986 and 1998. Twenty-six were poor surgical risk patients, 15 refused permanent stoma and 22 who were fit for surgery agreed to radiotherapy to avoid a permanent stoma. Clinical staging was done in 57 patients. Forty patients had T2 tumour and 23 had T3 tumour. Patients were offered combined modality treatment with EBRT (39 Gy in 13 fractions over 17 days) and contact radiotherapy boost (80 Gy in 3 fractions over 3 weeks). At median follow-up of 54 months, local control was achieved in 65 % and 86 % after salvage surgery for residual disease. Primary control rates and 5-year overall survival (patients <80 years) were 80 and 86 % for T2 disease. The respective figures for patients with T3 disease was 61 and 52 %. No severe grade 3 toxicity requiring colostomy was observed. Anorectal function was good in 92 % of patients. Rectal bleeding and bowel urgency were the most common long-term side effects. Two prognostic factors were found to be important. The tumour response after two fractions on day 21 and T stage of the tumour were found to be significant factors [15]. Gerard went further to conduct the only randomised trial (Lyon 96–02) to evaluate the role of contact radiotherapy in improving sphincter preservation for T2-T3 distal rectal cancer. Between 1996 and 2001, 88 patients were randomised between EBRT (36 Gy/13/17 days) and EBRT preceded by contact (Papillon) boost. Sphincter preservation was achieved in 76 %, compared to 44 % in the experimental group [16]. Much higher complete clinical responses (24 % vs. 2 %) and pCR or near-complete sterilization (57 % vs. 34 %) were observed in the contact boost arm compared to the standard arm. These results were maintained in Gerard’s recent update after 10 years’ follow-up [17]. He is proposing that the OPERA trial should reproduce these results, but organ preservation with local control at 2 years will be the primary end-point rather than sphincter preservation. Later he moved to Nice and updated his results for patients treated in Nice with contact X-ray brachytherapy from 2002 to 2009 [18]. The more recent update of his results up to 2009 using the new Papillon (Ariane) has shown further improvement due to better case selection with 90 % of patients achieving complete clinical response (cCR) and only 10 % had local recurrence ([19].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree