Complementary and alternative medicine is of great interest to patients with gastrointestinal disorders and some will choose to ask their health care providers about those therapies for which some scientific evidence exists. This review focuses on those therapies most commonly used by patients, namely acupuncture/electroacupuncture and various herbal formulations that have been the focus of clinical and laboratory investigation. A discussion of their possible mechanisms of action and the results of clinical studies are summarized.

Key points

- •

Complementary and alternative medicine is used by a significant percentage of individuals with chronic gastrointestinal disorders.

- •

Acupuncture and electroacupuncture are the modalities that have been most studied with respect to their effect on visceral hypersensitivity, gastric accommodation, and gastric emptying.

- •

Herbal formulations, such as STW 5 and Rikkunshito, may help improve some symptoms of functional dyspepsia, but more studies are needed to understand their mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy.

- •

No clinical studies have yet been conducted using marijuana or cannabinoids to treat symptoms of gastroparesis, although endocannibinoids have a wide array of effects on gastrointestinal function.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is used pervasively throughout the world with a prevalence ranging from 5% to 72%. Despite widespread patient interest, there is a need for health care providers to learn more about the vast array of specific practices, and to better understand why patients express interest in knowing more about them. Studies suggest that it is uncommon for most patients to abandon conventional therapy for alternative practices. For some patients with gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, CAM therapies may help provide a sense of control over their disease. Patients fearing that their questions may not be well received or that their conventional care practitioner is not knowledgeable, sometimes choose not to fully disclose their interest or their usage. In the United States, this issue resulted in the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine to launch the “Time to Talk” campaign in 2011 to encourage patients and their providers to openly discuss complementary practices. This article is intended to help those involved in the care of those with gastroparesis understand the modalities most commonly used and discussed by patients with gastroparesis.

CAM use by patients with GI disease or symptoms is not uncommon. A multicenter survey of pediatric patients followed in a GI clinic revealed that 40% of parents of pediatric patients with GI disorders use CAM therapies, with the most important predictors being the lack of effectiveness of conventional therapy, school absenteeism, and the adverse effects of allopathic medication. In a UK survey, 26% of patients with GI symptoms sought CAM therapy. A survey at a single UK academic center showed the incidence of CAM use was 49.5% for inflammatory bowel disease, 50.9% for irritable bowel syndrome, 20% for general GI diseases, and 27% for controls.

Studies reporting CAM use by patients with functional bowel disorders have centered primarily on those with irritable bowel syndrome. Relatively few studies exist describing the prevalence of CAM use by those with functional dyspepsia or gastroparesis. In the National Institutes of Health’s Clinical Gastroparesis Research Center’s registry of more than 600 patients, 22% reported using a CAM therapy at the time of initial enrollment (Lee 2014, unpublished data). Gastroparetic patients who used CAM were more likely to be women, white, college-educated, and nonsmokers. The therapies most commonly used by those in the registry were vitamins, herbal supplements, acupuncture, probiotics, and therapeutic massage (Lee 2014, unpublished data).

Several of these therapies are reviewed here with respect to gastroparesis, their proposed mechanisms of action, and results from clinical trials. Among various methods of CAM, herbal medicine and acupuncture/electroacupuncture (EA) are the only ones that have been applied in animal models of gastroparesis or impaired gastric motility. Compared with herbal medicine, relatively more reports are available in the literature studying the effects and mechanisms of acupuncture/EA on the pathophysiology of gastroparesis. In addition, a discussion of marijuana and cannabinoids also is included because of the general interest expressed by patients and family members and possible relevance to clinical care.

Acupuncture/Electroacupuncture

Acupuncture/EA affects impaired gastric accommodation, visceral hypersensitivity, and gastric dysmotility (gastric dysrhythmia, antral hypomotility, and delayed gastric emptying).

Electroacupuncture and Gastric Accommodation

When food enters the stomach, the proximal stomach relaxes during eating to accommodate the ingested food without producing a large increase in gastric pressure; this reflex is called gastric accommodation. Impaired gastric accommodation is commonly seen in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Clinically, it is difficult to treat impaired gastric accommodation in patients with gastroparesis or functional dyspepsia due to coexisting condition of antral hypomotility. Treatment of impaired accommodation with muscle relaxants or adrenergic agents would worsen antral hypomotility. On the other hand, treatment of antral hypomotility often worsens impaired gastric accommodation.

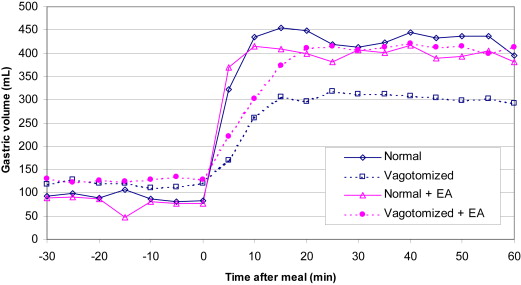

In a rodent model of diabetic gastroparesis (1-time injection of streptozotocin), EA at ST36 improved gastric accommodation and the effect was blocked by naloxone. In dogs, the same method of EA restored vagotomy-induced impairment in gastric accommodation but showed no effects on gastric accommodation in normal animals ( Fig. 1 ). In a recent clinical study, transcutaneous EA (electrical stimulation performed via electrodes placed on the acupuncture points) increased gastric accommodation in patients with functional dyspepsia, assessed by a nutrient drink test.

Electroacupuncture and Gastric Slow Waves

The gastric slow wave originates in the proximal stomach and propagates distally toward the pylorus. It determines the maximum frequency and propagation direction of gastric contractions. The gastric slow wave has a low frequency of 3 cycles per minute (cpm) in humans, and 5 cpm in dogs and rats. Dysrhythmia in gastric slow waves has been linked to impaired gastric motility, such as antral hypomotility and delayed gastric emptying. The effects of EA on gastric slow waves in patients with gastric motility disorders have been widely studied due to the availability of the noninvasive method of electrogastrography. Both EA and needleless transcutaneous EA have been consistently and robustly shown to improve gastric dysrhythmia.

In diabetic rats, acute EA increased the percentage of normal slow waves from 55% to 69%, and the effect was blocked by naloxone. In dogs, EA at ST36 was reported to reduce gastric dysrhythmia induced by duodenal distention or rectal distention, and the ameliorating effect was mediated via the opioid and vagal pathways. In a rodent study, the effect of EA on gastric slow waves was reported to be site-specific: EA at PC6 showed an inhibitory effect on gastric slow waves, whereas EA at ST36 enhanced gastric slow waves. In rats with thermal injury, EA at ST36 improved gastric slow waves with a concurrent suppression of inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6.

Electroacupuncture and Gastric Contractions

Coordinated and distally propagated gastric contractions or peristalsis is needed to empty the stomach. Effects and mechanisms of acupuncture/EA on gastric contractions have been investigated in several species, including rats, rabbits and dogs.

In anesthetized rats, antral contractions were enhanced with acupuncturelike stimulation in the limbs but inhibited with similar stimulation in the abdomen or lower chest region ; the excitatory effect was mediated via the vagal pathway, whereas the inhibitory effect was through the activation of sympathetic activity. In an in vitro study with diabetic rats, EA at ST36 at both low and high frequencies increased contractility of muscle strips from the gastric antrum and the effect was noted to involve the stem cell factor/c-kit pathway. In an in vivo study with the measurement of gastric contractions using strain gauge, EA at ST36 was reported to exert dual effects: enhancement of gastric contractions in rats with hypomotility and inhibition of contractions in rats with hypermotility.

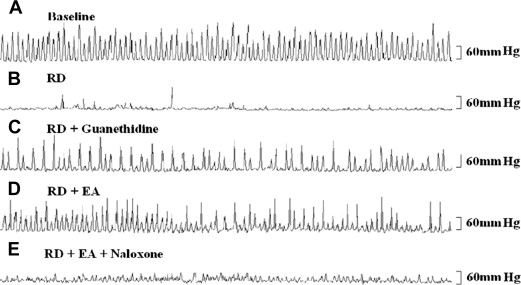

In dogs, EA at ST36 improved antral hypomotility induced with rectal distention. Regular antral contractions were measured by a manometric catheter placed in the antrum via a chronically implanted cannula in the middle of the stomach ( Fig. 2 A). Rectal distention substantially inhibited postprandial antral contractions (see Fig. 2 B) and the effect was reversed by guanethidine (see Fig. 2 C), suggesting a sympathetic mechanism. EA at ST36 dramatically enhanced antral contractions during rectal distention (see Fig. 2 D) and the effect was abolished by naloxone (see Fig. 2 E), suggesting an opioid mechanism.

Electroacupuncture and Gastric Emptying

With appropriate selection of acupoints and stimulation parameters, the prokinetic effect of EA on gastric emptying has been consistent and robust in both humans and animals ST36 is the most commonly used acupoint for improving gastric emptying and other components of gastric motility, such antral contractions and gastric slow waves. The stimulation frequency ranges from 4 Hz to 100 Hz, with the frequencies of 20 to 40 Hz being the most prevalent. The pulse width is typically set at 0.3 to 0.5 ms, although some studies failed to mention this important parameter. The stimulation amplitude is chosen at a level tolerable by the animals, ranging from 1 to 10 mA, depending on preparation.

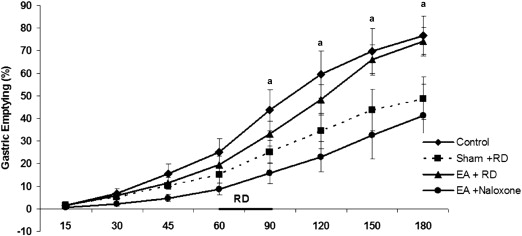

Gastric emptying was accelerated with EA in normal rats, rats with restrain stress, rats with thermal injury, and diabetic rats with gastroparesis. EA at both PC6 and ST36 or ST36 alone also accelerated gastric emptying in dogs with delayed gastric emptying induced by duodenal distention or rectal distention. A typical example showing the effect and mechanism of EA on rectal distention–induced delay in gastric emptying is presented in Fig. 3 .

The accelerative effect of EA on gastric emptying may be mediated via the vagal and opioid mechanisms evidenced by the assessment of vagal activity based on the spectral analysis of the heart rate variability and the blockage effect of atropine and naloxone. Other mechanisms also have been implicated. In diabetic rats, the accelerative effect of EA at ST36 was shown to involve the rescue of the damaged networks of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), such as inhibition of ICC apoptosis and enhancement of ICC proliferation. In rats with thermal injury, the improvement in gastric emptying with EA was noted to involve the inhibition of interleukin-6. Other mechanisms reported in the literature include enhancement of blood flow, activation of A delta and/or C afferent fiber, and involvement of the serotonin pathway.

Electroacupuncture and Visceral Hypersensitivity

The effects and mechanisms of EA on visceral hypersensitivity have been investigated in various animal models without gastroparesis. Acupuncture and EA have been most successfully applied for the treatment of pain. Therefore, in general, they are believed to exert analgesic effects on visceral pain as well.

In rats with neonatal colorectal chemical irritation, EA at ST36 reduced rectal distention–evoked abdominal electromyogram and the expression of 5HT-3 receptors in the colon. In rats with visceral hypersensitivity induced by colorectal distention, EA at ST37 and ST25 improved visceral hypersensitivity assessed by the abdominal withdrawal reflexes and reduced P2X2 and P2X3 receptor expressions in the dorsal root ganglion. The same method of EA also was reported to reduce the number of mucosal mast cells in the colon and the expressions of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus and substance P and substance P receptors in the colon of rats with irritable bowel syndrome. In our own laboratory, in rats with visceral hypersensitivity established by colorectal injection of acetic acid during the neonatal stage, EA at ST36 reduced visceral hyperalgesia and reversed the enhanced excitability of colon dorsal root ganglion neurons.

Clinical Studies of Acupuncture for Symptoms of Gastroparesis

Acupuncture has been used for the treatment of gastrointestinal ailments for thousands of years. Most clinical trials have focused on irritable bowel syndrome or the management of nausea and vomiting that arises postoperatively, or as the result of chemotherapy, pregnancy, or motion sickness. The acupuncture point thought to be most responsible for reducing nausea and vomiting is P6 (Pericardium 6), located 3 cm proximal to the wrist between the tendons of the flexor carpi radials muscle and palmaris longus muscle. The mechanisms by which P6 stimulation results in reduced nausea and vomiting have been discussed. Acupuncture also might affect gastric motor activity or restore gastric accommodation.

Although there have been several published studies and reviews on the role of acupuncture in postoperative nausea and chemotherapy-induced nausea, comparatively few randomized controlled clinical trials exist examining the effect of acupuncture for the treatment of functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. The results of some of these trials are summarized here:

- •

In 15 diabetic individuals with dyspeptic symptoms, cutaneous electrogastrography showed increased percentages of normal frequency, decreased percentages of tachygastria, and increased serum pancreatic polypeptide levels during and after EA. In a randomized controlled study of acupuncture delivered 5 times per week for 4 weeks in 72 patients with functional dyspepsia, significantly greater improvement was seen in the Symptom Index of Dyspepsia (SID) in those who received acupuncture versus sham acupuncture (non–acupuncture points). Quality of life, measured by Nepean Dyspepsia Index (NDI), improved significantly for the acupuncture group only. In that same study, a subset of the patients underwent cerebral positron emission testing after acupuncture. The increase in NDI score was significantly related to the decrease in glycometabolism in the insula, thalamus, brainstem, anterior cingulate cortex, and hypothalamus, suggesting acupuncture has a central effect.

- •

One of the largest randomized control studies of acupuncture for functional dyspepsia involved 720 patients randomized to 1 of 4 acupuncture treatment arms and 1 sham acupuncture arm. In addition, there was a sixth treatment arm in which patients received itopride, a prokinetic. All 4 active acupuncture arms and itopride resulted in significant improvement in the SID compared with sham acupuncture, particularly with regard to early satiety. In addition, the 4 acupuncture arms resulted in significant improvement in quality of life (NDI) compared with sham acupuncture, but itopride showed no improvement in quality of life.

- •

Acupuncture was compared with standard promotility drugs in improving gastric emptying in a group of critically ill patients receiving enteral feeding. Delayed gastric emptying was defined as a gastric residual volume greater than 500 mL for 2 days or more. Bilateral prolonged intermittent transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation of acupuncture point Neiguan (P6) was delivered daily using a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation device for 5 days. There was no statistical difference in the types of drugs delivered to both groups of patients during the study. Acupoint stimulation significantly improved delayed gastric emptying in critically ill patients when compared with standard prokinetics.

- •

Finally, a small, randomized single-blinded study of EA in diabetic patients with gastroparesis over 2 weeks reduced the dyspeptic symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis and accelerated solid gastric emptying.

Thus, acupuncture continues to be one modality that attracts patients with chronic nausea and vomiting, early satiety, postprandial bloating, and epigastric pain. Its mechanisms of action are not yet fully understood, and it remains uncertain how frequent the acupuncture treatments should be delivered, for how long, and for what duration of each session. Because acupuncture has relatively few side effects, it seems reasonable to recommend this therapy for those individuals strongly interested in using this modality or in those who have exhausted pharmacologic attempts at managing their symptoms.

Herbal Formulations/Supplements (Including Marijuana)

STW 5 (Iberogast)

STW 5 (Iberogast; Steigerwald GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) is an herbal formulation originating in Germany containing 9 extracts ( Iberis amara planta totalis , Chelidonii herba , Cardui mariae fructus , Melissae folium , Carvi fructus , Liquiritiae radix , Angelicae radix , Matricariae flos , Menthae piperitae folium ). Prescribed primarily to treat the symptoms of functional dyspepsia, its effects may be due to its ability to increase gastric accommodation and perhaps affect anteroduodenal motility, as shown in healthy male volunteers. It does not appear to accelerate gastric emptying of solids, however. STW 5 may have other effects, including modulating intestinal afferent sensitivity as shown in male Wistar rats and some of its components exert antispasmolytic, prosecretory, and anti-inflammatory effects in the small intestine and colon in animal models.

A randomized placebo-controlled trial using STW 5 in patients with functional dyspepsia for 8 weeks showed it to have a slightly better improvement in Gastrointestinal Symptom Score (GIS) compared with placebo with no difference in adverse effects. Another randomized placebo double-blind study of patients with functional dyspepsia also documented improvement in the GIS in those randomized to STW 5, but no acceleration in gastric emptying in those with documented gastroparesis. The lack of correlation between symptom improvement and accelerated gastric emptying is not surprising and similar to what has been observed with other therapies, such as electrical gastric stimulation.

Rikkunshito

Rikkunshito (RKT), a Kampo (Japanese herbal) medicine (also known as TJ-43 or Liu-Jun-Zi-Tang, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine), contains extracts of Atractylodis lanceae rhizoma , Ginseng radix , Pinelliae tuber , Hoelen , Zizyphi fructus , Aurantii nobilis percarpium , Glycyrrhizae radix , and Zingiberis rhizoma . RKT when instilled into the stomachs of dogs has been shown to accelerate gastric emptying and stimulate phasic contractions of the duodenum and jejunum, an effect not blocked by vagotomy. In the isolated guinea pig stomach, Liu-Jun-Zi-Tang enhanced gastric adaptive relaxation induced by luminal distention, which was not seen with metoclopramide, trimebutine, or cisapride.

RKT was compared against domperidone in a randomized controlled trial of 27 patients with functional dyspepsia. After 4 weeks, there was improvement in the symptoms of both groups as measured by their Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale questionnaire scores. However, in a randomized controlled trial of RKT in 247 patients with functional dyspepsia, 2.5 g RKT administered 3 times daily for 8 weeks was associated with reduced symptoms of epigastric pain and postprandial fullness, but the primary end point of reduced global symptom assessment was not met. In a separate randomized controlled trial of patients with proton pump inhibitor refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, addition of RKT significantly reduced the frequency of GERD symptoms in patients with nonerosive GERD.

How RKT works is not well understood, as a study in healthy volunteers suggested that RKT does not affect esophageal motility, decrease postprandial gastroesophageal acid, nonacid reflux events, or accelerate esophageal clearance time. It was reported to promote gastric adaptive relaxation in patients with functional dyspepsia.

Simotang

Simotang (decoction of 4 powered drugs), one of the most commonly used Chinese herbal formulas, was administrated to chronically stressed mice daily for 7 days for the assessment of its effect on gastrointestinal motility. In comparison with the placebo treatment, Simotang significantly increased gastric emptying and intestinal propulsion, increased serum motilin, and decreased the expressions of cholecystokinin-positive cells and genes in the small intestine, spinal cord, and brain.

Taraxacum officinale

Taraxacum officinale is a traditional herbal medicine commonly used for treating abdominal illness. One special preparation of Taraxacum officinale was found to increase gastric emptying in rats with potency comparable to cisapride. In in vitro studies, it increased gastric contractions and decreased pyloric contractions, mediated by the cholinergic mechanism.

Dai-kenchu-to

Dai-kenchu-to is another herbal medicine used to treat gastrointestinal diseases. Its main ingredients include Zanthoxylum fruit, ginseng root, and dried ginger rhizome. In dogs, intraluminal administration of Dai-kenchu-to was reported to induce gastric and intestinal contractions. In another canine study, however, only the main ingredient, dried ginger rhizome, was noted to elicit phase contractions in the stomach and the effect was mediated through cholinergic 5HT-3 receptors.

Modified Xiaoyao San

Modified Xiaoyao San (MXS, or Jiawei xiaoyao san, Jia-Wey Shiau-Yau San, called Kami shoyo san in Japanese) is a Chinese herbal formulation widely prescribed in Asia to treat gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal distention, hiccups, anorexia, and dry or bitter taste in the mouth. MXS is mixture of 14 herbs: Radix bupleuri , Radix angelicae sinensis , Radix paeoniae alba , Rhizoma atractylodis macrocephalae , Poria , Rhizoma zingiberis recens , Radix glycyrrhizae , Herba menthae , Cortex moutan , Fructus gardeniae , Cortex magnoliae officinalis , Fructus aurantii , Radix puerariae , and Fructus jujubae . Qin and colleagues recently performed a literature review, identified 14 randomized controlled studies in which MXS was used alone or compared with a prokinetic agent, but was unable to draw a conclusion about its efficacy because all studies were of poor quality.

Banxiaxiexin decoction

Banxiaxiexin decoction (BXXD), a traditional Chinese herbal medicine containing 7 commonly used herbs ( Pinellia ternata , Radix scutellariae , Rhizoma zingiberis , Panax ginseng , Radix glycyrrhizae , Coptis chinensis , and Fructus jujubae ) has been used for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia. A recent review of the literature indicated that only small studies have so far been published, from which no definite efficacy or safety conclusions could be made.

Marijuana ( Cannibis sativa )

Marijuana is included in this article because of tremendous interest expressed by patients and family members, even though there are no published clinical trials on marijuana and gastroparesis. Legalization of the sales of marijuana in 20 US states, and the perception of increased access and medical endorsement, likely contributes to this interest and may result in greater use by patients with functional GI disorders. Cannabis has been used as an herbal remedy in many cultures for the relief of nausea and other GI complaints. Cannabis contains several active cannabinoids, such as its major constituent Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, and these vary in their pharmacologic effects and. In recent years, the components of the endocannabinoid system have been detailed in several excellent recent reviews to which the reader is directed.

Endocannabinoids, such as anandamide and 2-arachidonylglycerol, may affect gastric acid secretion, lower esophageal relaxation, visceral hypersensitivity, intestinal motility, inflammation, and secretion and ion transport. Endocannabinoids exert multiple pharmacologic effects via its primary receptors, CB1 and CB2, but also the Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). Effects of cannabinoids on gut motility and visceral sensation are mediated through these receptors, which are expressed on enteric neurons as well as macrophages. The highest density of CB1 and CB2 receptors are found in the myenteric and submucosal plexuses. Additionally, activation of TRPV1 receptors in the hippocampus and the periaqueductal gray matter may contribute to the anticonvulsant and anxiolytic effects of cannabinoids, respectively.

In the gut, the endocannabinoid system is modulated by the state of satiety and the presence of intestinal inflammation. Food deprivation increases CB1 receptor expression in vagal afferent neurons and increases anandamide levels. In rodent studies, cannabinoids slow intestinal transit. They also may inhibit production of tumor necrosis factor in the setting of experimentally induced intestinal inflammation.

Perhaps the greatest potential therapeutic effect for patients with gastroparesis may be the effect of cannabinoids on nausea and vomiting. Indirect activation of somatodendritic 5-HT(1A) receptors in the dorsal raphe nucleus may explain its antiemetic effects. Endocannabinoids, such as anandamide, reduce emesis through CB1 or TRPV1 receptors in the brainstem to control vomiting.

Endocannabinoid pathways could theoretically be affected by developing drugs that interfere with production or degradation of endocannabinoids or expression of their receptors. Most clinical trials have focused on using synthetic cannabinoids developed to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. The most clinically relevant studies are those using synthetic cannabinoids as opposed to the whole herb itself. There are 2 cannabinoid derivatives approved by the Food and Drug Administration, dronabinol and nabilone, for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, but these are no longer considered first-line agents, given the availability of 5HT3 antiemetics that are viewed as safer.

There are no studies of cannabinoids in the treatment of symptoms associated with dyspepsia or gastroparesis. There are still many concerns about the use of cannabinoids for managing symptoms due to functional GI disorders. Furthermore, extrapolating any of the effects observed with synthetic cannabinoids to the whole herb cannot be made. There are safety concerns around marijuana, in that it could be addictive and it may be as harmful as tobacco smoking. Moreover, there are now numerous case reports and series of marijuana hyperemesis syndrome occurring in daily users of marijuana. The symptoms include nausea, vomiting, a need to frequently bathe in hot water, and abdominal pain. Cessation of marijuana smoking may improve symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree