Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis are common causes of chronic watery diarrhea that are characterized by distinct histopathologic abnormalities without endoscopically visible lesions and are summarized as microscopic colitis. Several variants of microscopic colitis have been described, although their clinical significance still has to be defined. Preserved mucosal architecture is a histologic hallmark of microscopic colitis and distinguishes the disease from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In addition to architectural abnormalities, the diagnosis of IBD rests on characteristic inflammatory changes. Differential diagnosis of IBD mainly includes prolonged infection and diverticular disease–associated colitis, also known as segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis.

- •

Close communication between gastroenterologists and pathologists is necessary for accurate classification of patients with chronic diarrhea because there is considerable histologic overlap among different disease entities.

- •

Endoscopy with random mucosal biopsy is the only means of verifying the diagnosis of microscopic colitis, and its importance has been widely recognized.

- •

Mast cell (mastocytic) colitis has recently emerged as another condition associated with chronic diarrhea, but its significance still has to be defined.

- •

Preserved mucosal architecture is the histologic hallmark of microscopic colitis and distinguishes the disease from inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis in remission.

Introduction

Diarrhea is defined in terms of stool frequency, consistency, volume, or weight. Acute diarrhea is usually caused by infections or toxic agents. In contrast, chronic diarrhea usually has noninfectious causes. Although there is no general consensus on the duration of symptoms that differentiate acute from chronic diarrhea, most clinicians will agree that symptoms persisting for longer than 4 weeks suggest a noninfectious cause and merit further investigation. Six to 8 weeks, however, may provide a clearer distinction. According to the guidelines published by the British Society of Gastroenterology, chronic diarrhea is defined as the abnormal passage of 3 or more loose or liquid stools per day for more than 4 weeks or a daily stool weight greater than 200 g/d.

The prevalence of chronic diarrhea varies depending on definition and the studied population and has been reported to be 4% to 5% in the general population and 7% to 14% in an elderly population. Routine workup often includes endoscopic evaluation of the small and large bowel, and histological assessment of mucosal biopsies is an integral part of this procedure. In a study that has examined the prevalence of colonic pathologic conditions in patients with non–HIV-related chronic diarrhea, 15% of patients had histologic abnormalities. The most common diagnoses were microscopic (lymphocytic and collagenous) colitis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. Routine ileoscopy may enhance the diagnostic yield, and it has been suggested that in patients with chronic diarrhea, colonoscopy and ileoscopy with biopsy may lead to a definitive diagnosis in approximately 15% to 20% of cases. Although the examination of a biopsy specimen without clinical information can avoid cognitive bias, the full benefit of the pathologist’s experience and opinion can only be obtained if appropriate clinical information is available.

According to the American Gastroenterological Association’s technical review on the evaluation and management of chronic diarrhea, the disorders that can be diagnosed by endoscopic mucosal inspection mainly include Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, but melanosis coli, ulceration, and large colorectal polyps and tumors may also be identified as underlying causes. Diseases with mucosae that seem normal on endoscopic inspection but are associated with histologic abnormalities include microscopic colitis, amyloidosis, and some rare infections.

This review starts with a description of the normal anatomy because awareness of the range of normal, noninflamed, colorectal histology may help to avoid clinically useless terms, such as mild inflammatory changes or mild nonspecific colitis/proctitis. In its main section, the review focuses on the different forms of microscopic colitis, including mast cell (mastocytic) enterocolitis, and on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including various aspects of differential diagnosis.

Normal histology

The colorectal mucosa is flat and has no villi, as opposed to normal small bowel mucosa. Sections cut perpendicular to the surface show the crypts as straight tubes in parallel alignment that extend from immediately above the muscularis mucosae to the mucosal surface. The crypts are more or less closely packed and evenly distributed (>6 per millimeter). The distances between the individual crypts and their internal diameters are fairly stable, yet some variation and slight alterations in crypt configuration can be present in healthy individuals, particularly in the region of lymphoid follicles and innominate groves. Under normal conditions, the branching of crypts is rarely observed (<1 per millimeter). In a well-oriented section, crypt shortening (atrophy) is generally absent. Of note, mild uniform crypt shortening can reflect tangential cutting and is of no importance if the biopsy specimen is otherwise normal.

The luminal surface of the mucosa is covered by a single-cell layer of columnar epithelium composed of absorptive and goblet cells, resting on a thin, regular collagen table. Lymphocytes (CD3+/CD8+ T cells) may occasionally be present between surface cells (intraepithelial lymphocytes [IEL]), their number not exceeding 5 per 100 epithelial cells. The cell population lining the crypts is more complex. In addition to mature absorptive and goblet cells, neuroendocrine and Paneth cells are found, the latter only in the caecum and ascending colon. At the base of the crypts, immature precursor (stem) cells reside within the so-called stem cell niche. These pluripotent cells are capable of unlimited self-renewal and divide asymmetrically with one daughter cell residing in the niche and the other daughter cell migrating upward along the crypt axis. These latter cells are named transient amplifying cells. They represent the main proliferation compartment within the crypt and ultimately differentiate into the 4 mature cell types described earlier. In the luminal part of the crypt, cells have lost the ability to divide, but they become more functionally mature until they eventually exfoliate from the surface. This journey along the crypt axis normally takes between 72 and 192 hours, leading to renewal of the colonic surface epithelium every 3 to 8 days.

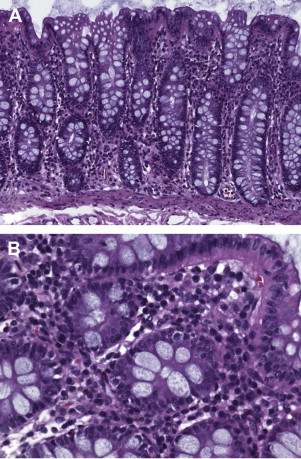

Inflammatory cells are normally present in varying numbers within the lamina propria and are responsible for the local immunologically mediated host defense. The cells are diffusely distributed, with most cells localized in the superficial third of the mucosa (superficial vs basal third 2:1). In addition, up to 2 lymphoid aggregates or follicles in a 2-mm biopsy specimen may be regarded as normal. Thus, these cells do not represent chronic inflammation ( Fig. 1 ).

Under normal conditions, plasma cells (B cells) are the predominant round cell, and T lymphocytes and macrophages represent other common inhabitants of the lamina propria. Myeloid cells that are normally present include eosinophils and mast cells. Their number is highly variable, but they are relatively rare; eosinophils account for approximately 3.5% and mast cells account for approximately 2% of the cells within the lamina propria. The detection of mast cells requires special staining. Of note, mast cell numbers that are assessed by immunohistochemistry (antibodies directed against tryptase, KIT/CD117) are higher than those detected by toluidine blue staining because the latter method only stains the minority of activated cells (ie, degranulated cells), which may predominate in areas of inflammation. Neutrophils should not be present normally in either the surface or the crypt epithelium.

The cellular composition of the lamina propria varies between different anatomic segments of the large bowel. The density of mucosal lymphocytes is significantly higher in the right colon than in the left colon and particularly the rectum. Likewise, the absolute and relative number of mast cells within the lamina propria is lowest in the rectosigmoid, whereas the number of eosinophils does not change significantly from segment to segment.

Within the lamina propria, fibroblasts are found randomly distributed throughout the lamina propria. Their number is highest in the most superficial portion of the lamina propria adjacent to the basement membrane of the surface epithelium as well as encompassing the crypts (pericryptal myofibroblasts). There is considerable crosstalk between these latter cells and the cells within the stem cell niche, which is essential for mucosal integrity and differentiation. Immediately below the basement membrane complex of superficial epithelial cells, a collagen layer is found that is no thicker than 3 to 5 μm. Of note, tangential cutting of biopsy specimens may cause apparent expansion of the basement membrane. Together with the eosinophilic subnuclear zone of surface epithelial cells, this may give a false impression of a thickened subepithelial collagen layer.

Normal histology

The colorectal mucosa is flat and has no villi, as opposed to normal small bowel mucosa. Sections cut perpendicular to the surface show the crypts as straight tubes in parallel alignment that extend from immediately above the muscularis mucosae to the mucosal surface. The crypts are more or less closely packed and evenly distributed (>6 per millimeter). The distances between the individual crypts and their internal diameters are fairly stable, yet some variation and slight alterations in crypt configuration can be present in healthy individuals, particularly in the region of lymphoid follicles and innominate groves. Under normal conditions, the branching of crypts is rarely observed (<1 per millimeter). In a well-oriented section, crypt shortening (atrophy) is generally absent. Of note, mild uniform crypt shortening can reflect tangential cutting and is of no importance if the biopsy specimen is otherwise normal.

The luminal surface of the mucosa is covered by a single-cell layer of columnar epithelium composed of absorptive and goblet cells, resting on a thin, regular collagen table. Lymphocytes (CD3+/CD8+ T cells) may occasionally be present between surface cells (intraepithelial lymphocytes [IEL]), their number not exceeding 5 per 100 epithelial cells. The cell population lining the crypts is more complex. In addition to mature absorptive and goblet cells, neuroendocrine and Paneth cells are found, the latter only in the caecum and ascending colon. At the base of the crypts, immature precursor (stem) cells reside within the so-called stem cell niche. These pluripotent cells are capable of unlimited self-renewal and divide asymmetrically with one daughter cell residing in the niche and the other daughter cell migrating upward along the crypt axis. These latter cells are named transient amplifying cells. They represent the main proliferation compartment within the crypt and ultimately differentiate into the 4 mature cell types described earlier. In the luminal part of the crypt, cells have lost the ability to divide, but they become more functionally mature until they eventually exfoliate from the surface. This journey along the crypt axis normally takes between 72 and 192 hours, leading to renewal of the colonic surface epithelium every 3 to 8 days.

Inflammatory cells are normally present in varying numbers within the lamina propria and are responsible for the local immunologically mediated host defense. The cells are diffusely distributed, with most cells localized in the superficial third of the mucosa (superficial vs basal third 2:1). In addition, up to 2 lymphoid aggregates or follicles in a 2-mm biopsy specimen may be regarded as normal. Thus, these cells do not represent chronic inflammation ( Fig. 1 ).

Under normal conditions, plasma cells (B cells) are the predominant round cell, and T lymphocytes and macrophages represent other common inhabitants of the lamina propria. Myeloid cells that are normally present include eosinophils and mast cells. Their number is highly variable, but they are relatively rare; eosinophils account for approximately 3.5% and mast cells account for approximately 2% of the cells within the lamina propria. The detection of mast cells requires special staining. Of note, mast cell numbers that are assessed by immunohistochemistry (antibodies directed against tryptase, KIT/CD117) are higher than those detected by toluidine blue staining because the latter method only stains the minority of activated cells (ie, degranulated cells), which may predominate in areas of inflammation. Neutrophils should not be present normally in either the surface or the crypt epithelium.

The cellular composition of the lamina propria varies between different anatomic segments of the large bowel. The density of mucosal lymphocytes is significantly higher in the right colon than in the left colon and particularly the rectum. Likewise, the absolute and relative number of mast cells within the lamina propria is lowest in the rectosigmoid, whereas the number of eosinophils does not change significantly from segment to segment.

Within the lamina propria, fibroblasts are found randomly distributed throughout the lamina propria. Their number is highest in the most superficial portion of the lamina propria adjacent to the basement membrane of the surface epithelium as well as encompassing the crypts (pericryptal myofibroblasts). There is considerable crosstalk between these latter cells and the cells within the stem cell niche, which is essential for mucosal integrity and differentiation. Immediately below the basement membrane complex of superficial epithelial cells, a collagen layer is found that is no thicker than 3 to 5 μm. Of note, tangential cutting of biopsy specimens may cause apparent expansion of the basement membrane. Together with the eosinophilic subnuclear zone of surface epithelial cells, this may give a false impression of a thickened subepithelial collagen layer.

Microscopic colitis

Collagenous and Lymphocytic Colitis

Microscopic colitis is a common cause of chronic or recurrent watery (nonbloody) diarrhea. The term was initially coined in 1980 to describe patients with chronic watery diarrhea and minor histologic changes with no other evident causes despite extensive workup. Currently, microscopic colitis is used as an umbrella term that includes 2 major conditions without endoscopic or radiologic lesions but with histologic abnormalities that are traditionally termed collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis .

Collagenous colitis was first described in 1976 in a woman with chronic diarrhea, normal barium enema and sigmoidoscopy, and findings of a thickened subepithelial collagen band and an increased IEL count on histology. The term lymphocytic colitis was introduced in 1989 in a similar clinical and histologic context without the finding of a thickened subepithelial collagen band. It is likely that the two conditions are part of a spectrum because the clinical features are similar and there is substantial overlap in histologic findings. In a recent investigation, histologic findings suggested coexistence with the other type of microscopic colitis in 48% of patients with collagenous colitis and in 24% of patients with lymphocytic colitis, respectively.

In a large epidemiologic study from Sweden, microscopic colitis accounted for approximately 10% of all patients investigated for chronic (nonbloody) diarrhea and for almost 20% of those older than 70 years. The number of patients diagnosed with lymphocytic colitis is similar to that of collagenous colitis. The disease occurs predominantly in older adults, with the diagnosis most commonly made in the sixth to seventh decade (average age at diagnosis is 53–69 years). However, a wide age range has been reported, including pediatric cases. Women are more commonly affected than men, with a female-to-male ratio ranging from 3:1 to 9:1 for collagenous colitis and 1:1 to 6:1 for lymphocytic colitis, respectively. The incidence has increased over time to levels comparable with other forms of IBD. The reason for this increase is not clear, but growing awareness of the disease may be partially responsible. One study showed that microscopic colitis is diagnosed less commonly in small nonacademic centers.

The pathogenesis of microscopic colitis is largely unknown. Most cases are idiopathic, but an abnormal immunologic reaction to a luminal antigen (eg, infectious agents and drugs, such as proton pump inhibitors and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), possibly in a genetically predisposed individual, seems to play a major role. Notably, 20% to 60% of patients with lymphocytic colitis and 17% to 40% of patients with collagenous colitis suffer from autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, collagen vascular diseases, or thyroid disorders. There is also a strong association with celiac disease, which is detected in 6% to 27% of patients with lymphocytic colitis and 8% to 17% of patients with collagenous colitis, respectively. In a recent study evaluating the incidence of microscopic colitis in a large database of patients with celiac disease, microscopic colitis was found in 44 of 1009 patients (4.3%), which corresponds to a 70-fold increased risk compared with that in the general population.

The excessive collagen deposition in collagenous colitis has been related to alterations in subepithelial myofibroblast function, possibly leading to matrix or collagen overproduction. However, impaired degradation of extracellular matrix proteins (ie, impaired fibrolysis) may also play a major role.

Although by definition, in microscopic colitis the mucosa of the large intestine should be normal on endoscopic inspection, subtle changes, such as mild edema and erythema as well as an abnormal vascular pattern, may occasionally be seen. If colonic ulcers are present, these are likely to be caused by NSAIDs.

The key histologic feature of microscopic colitis is an increased number of surface IEL with little to no disruption of the mucosal architecture ( Fig. 2 A). On sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), IEL are characterized by mostly round, compact nuclei with a dense chromatin pattern, slightly irregular nuclear outline, and perinuclear halo. Most investigators refer to a cutoff of 20 or more IEL per 100 surface epithelial cells, but some also refer to 15 or more IEL (median 30, range 10–66). The terminal ileum may be affected in both lymphocytic and collagenous colitis. One study analyzing ileal biopsies from patients with lymphocytic and collagenous colitis (none of them had celiac disease) proved the presence of 5 or more IEL per 100 surface epithelial cells to be highly specific for microscopic colitis. Compared with healthy individuals, there is increased mononuclear inflammation within the lamina propria with even distribution (ie, loss of the normally decreasing inflammatory cell density gradient toward the muscularis mucosae) (see Fig. 2 B). Neutrophils may also be present, and active cryptitis with occasional crypt abscess formation has been reported to occur in 30% to 38% of patients, although acute inflammation should not predominate within the inflammatory infiltrate.

In patients with collagenous colitis, a thickened collagen layer is seen underneath the surface epithelium, which is most evident between crypts (see Fig. 2 C). Most investigators agree that the thickness of the collagen layer should exceed 10 μm (often 15–30 μm, up to 70 μm) on well-oriented biopsies (ie, biopsies cut perpendicular to the mucosal surface). Diarrhea is commonly noted when the collagen layer exceeds 15 μm. Care should be taken to avoid the misinterpretation of a tangentially cut basement membrane (see earlier discussion). In selected cases, additional stains, such as trichrome staining or tenascin immunohistochemistry, may be helpful. The collagen entraps capillaries and inflammatory cells, leading to nuclear abnormalities of enclosed lymphocytes (twisted lymphocytes).

Secondary changes to the surface epithelium are common and are usually more pronounced in collagenous than in lymphocytic colitis. They include flattening or degeneration (cytoplasmic vacuoles, pyknotic nuclei) of columnar cells, or both, and mucin depletion. In collagenous colitis, the detachment of surface epithelial cells from subepithelial collagen represents a common histologic feature (see Fig. 2 D). Occasionally, focal IBD-like inflammatory changes and Paneth cell metaplasia in the right colon (44% in collagenous colitis, 14% in lymphocytic colitis) may be observed. Crypt distortion, shortening (atrophy), or branching, however, are not features of microscopic colitis. In fact, the overall absence of crypt architectural irregularities in lymphocytic and collagenous colitis is the major difference between microscopic colitis and IBD. Box 1 summarizes the key morphologic features of lymphocytic and collagenous colitis.

Lymphocytic colitis

- •

Increased number of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes (≥20 per 100 epithelial cells)

- •

Surface epithelial damage (flattening, mucin depletion)

- •

Increased (and homogeneously distributed) mononuclear inflammation in the lamina propria (plasma cells > lymphocytes)

- •

Thickening (<10 μm) of subepithelial collagen layer possible

- •

Focal IBD-like changes (cryptitis, Paneth cell metaplasia) possible

Collagenous colitis

- •

Diffusely distributed and thickened subepithelial collagen layer greater than or equal to 10 μm (not all samples may be involved)

- •

Surface epithelial damage (flattening, detachment)

- •

Increased (and homogeneously distributed) mononuclear inflammation in the lamina propria (plasma cells > lymphocytes)

- •

Increased number of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes possible

- •

Focal IBD-like changes (cryptitis, Paneth cell metaplasia) possible

The reliability of using flexible sigmoidoscopy in making the diagnosis is of some controversy. Nonuniform distribution of the subepithelial collagen band has been reported in collagenous colitis with less thickening in the rectosigmoid. Likewise, IEL counts were found to be increased in the right compared with the left colon in lymphocytic colitis. As a consequence, earlier studies mostly recommended the use of colonoscopy in the workup of patients with chronic diarrhea in order not to miss affected individuals. However, in a large systematic investigation of 809 patients evaluated for chronic diarrhea who had no endoscopically visible abnormalities on colonoscopy, 80 (10%) were found to have microscopic colitis, all of whom had evidence of disease in the left colon. In another recent study, 95% of patients with collagenous colitis and 98% of patients with lymphocytic colitis had diagnostic histopathology in both the right and the left colon, and normal histology in biopsies obtained from the left colon had a high negative predictive value for microscopic colitis. Biopsy material obtained only from the rectum, however, is known to have low sensitivity with respect to the diagnosis of microscopic colitis.

Thus, the advantages of flexible sigmoidoscopy over total colonoscopy must be weighed against the marginally increased diagnostic yield of colonoscopy regarding microscopic colitis. Colonoscopy may be reserved for those patients in whom results of distal biopsies obtained on sigmoidoscopy were normal or inconclusive. In these patients, a full colonoscopic examination with sampling of both the transverse and the ascending colon should be completed. However, this suggestion is limited to patients thought to have microscopic colitis and should not be extended to the evaluation of patients with diarrhea in general because it does not take into account proximal colonic lesions (eg, caused by Crohn’s disease), which may only be accessible by colonoscopy.

Variants of Microscopic Colitis

The spectrum of morphologic changes associated with chronic watery (nonbloody) diarrhea seems to be broader than originally thought. In 30% of patients, there are only minor histologic abnormalities, such as increased cellular density (plasma cells and lymphocytes) within the lamina propria, whereas IEL counts are not significantly elevated (between 5 and 20 per 100 surface epithelial cells) and the subepithelial collagen bands measure only between 5 and 10 μm in thickness.

Because these patients do not fulfill the criteria for classic lymphocytic colitis or collagenous colitis, they are usually not treated. Follow-up endoscopic biopsies, however, may render changes diagnostic for microscopic colitis; according to a recent study, as much as 30% of cases of microscopic colitis are diagnosed only on repeated endoscopy.

Some investigators have offered the term microscopic colitis not otherwise specified (NOS) for these cases, whereas others refer to these cases with incomplete findings of microscopic colitis as atypical microscopic colitis , incomplete microscopic colitis , or paucicellular lymphocytic colitis . It has been suggested to sign out these cases in a more descriptive way as epithelial lymphocytosis (not diagnostic for lymphocytic colitis) , and other conditions should be considered, such as a late phase of infectious colitis. The identification and reporting of these borderline cases could be the pathologist’s contribution to reduce the risk of missing patients with a treatable cause of diarrhea.

It currently remains unsolved whether patients with classic lymphocytic and collagenous colitis and patients with incomplete histologic findings should be regarded as one clinical entity. A recent immunohistologic study evaluating the expression of CD25+ regulatory T cells and FOXP3 in mucosal biopsies has shown discordant profiles in classic lymphocytic colitis and paucicellular lymphocytic colitis. This finding suggests different pathogenetic mechanisms, thereby arguing against paucicellular lymphocytic colitis as a minor form of classic lymphocytic colitis.

The term cryptal lymphocytic coloproctitis has been introduced to describe patients with chronic watery (nonbloody) diarrhea and significant intraepithelial lymphocytosis within the crypt epithelium, yet not within the surface epithelium. Patients with this peculiar histologic pattern are rare, and the significance of the diagnosis is largely unknown. Microscopic colitis with giant cells refers to the presence of multinucleated giant cells within the lamina propria in otherwise classic lymphocytic or collagenous colitis. These giant cells are of histiocytic origin and seem to form through histiocyte fusion. Their presence does not seem to confer any clinical significance and may be regarded as a histologic curiosity.

Other reported rare variants or presumed subtypes of microscopic colitis, such as pseudomembranous collagenous colitis and microscopic colitis with granulomatous inflammation, have been described. It is currently unclear whether these are specific entities. An overview is given in Fig. 3 . Furthermore, several other conditions are characterized by diarrhea without endoscopically visible lesions but with abnormal histology. Examples are intestinal spirochetosis, postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome, and IBD in remission; for a review, see Geboes.