Colonoscopic polypectomy is the most effective visceral cancer prevention tool in clinical medicine. In general, risks associated with the technique of polyp removal should match the likelihood that the polyp will become or already is malignant (eg, low-risk technique for low risk for malignant potential). Cold techniques are preferred for most diminutive polyps. Polypectomy techniques must be effective and minimize complications. Complications can occur even with proper technique, however. Aggressive evaluation and treatment of complications helps ensure the best possible outcome.

Colonoscopic polypectomy is the most effective visceral cancer prevention tool in clinical medicine. Two cohort studies have shown that polypectomy prevents colorectal cancer . The National Polyp Study estimated that polypectomy prevented 76% to 90% of incident colorectal cancers (CRC), by comparing the rates of incident cancers after a clearing colonoscopy with the expected rates based on reference populations . Another cohort of patients who had adenoma was calculated to incur an 80% reduction in incident CRC using similar methodology . A randomized controlled trial comparing flexible sigmoidoscopy, with colonoscopy and polypectomy for any detected polyp, versus no screening reported an 80% reduction in CRC incidence in the screened group . Colonoscopy is clearly imperfect in protecting against CRC, however . Two studies have suggested that 27% to 31% of incident cancers after colonoscopy result from ineffective polypectomy . All colonoscopists must therefore be highly proficient in polypectomy. Polypectomy has risks, however. The removal of any colon polyp should balance the likelihood that the polyp will turn into cancer with the risks associated with the technique used for its removal.

Optical Enhancement Techniques

Colonoscopic technology has undergone numerous recent innovations that enhance its diagnostic capabilities. Optical enhancement could potentially improve the exposure of colonic mucosa, the detection of flat lesions, and the determination of histology in real time ( Box 1 ). Because the focus of this article is polypectomy, we do not review techniques for improved detection, but focus on the assessment of polyps in real time before polypectomy because these technologies may assist in determining whether polypectomy is necessary.

See behind folds better

- •

Wide-angle colonoscopy

- •

Cap-fitted colonoscopy

- •

Third-Eye Retroscope

See flat lesions better

- •

Pancolonic chromoendoscopy

- •

Narrow band imaging

- •

High definition

- •

Autofluorescence

Interpret histology in real time

- •

Chromoendoscopy with high magnification

- •

Narrow band imaging

- •

Confocal laser microscopy

- •

Autofluorescence

Generally, all adenomas, or potential adenomas, should be removed during colonoscopy, as should hyperplastic polyps in the proximal colon, particularly larger hyperplastic polyps . Larger Peutz-Jeghers polyps and juvenile polyps should also be removed because of a risk for adenomatous transformation. Small distal colon hyperplastic polyps are the most commonly seen lesions for which there is no clear benefit from removal. Similarly, mucosal polyps and lymphoid hyperplasia, along with inflammatory polyps and true filiform pseudopolyps in inflammatory bowel disease, need not be removed during colonoscopy.

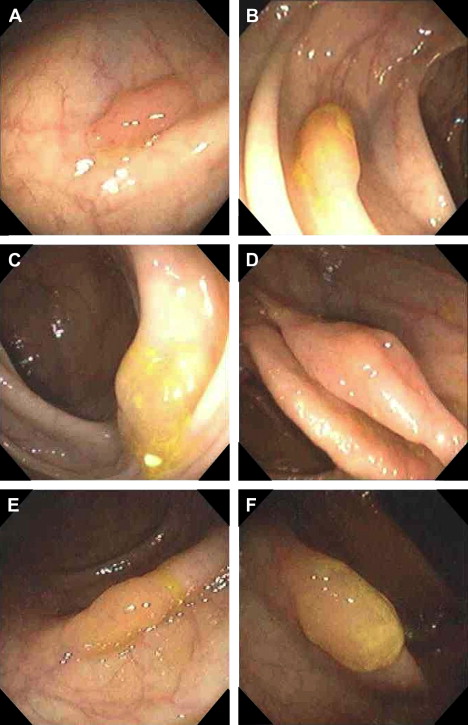

Clues about polyp histology are observed with white light. Diminutive, pale, sessile lesions in the distal colon, sometimes with visible blood vessels running across the surface, or that flatten with insufflation, are typically hyperplastic . Large proximal colonic polyps that are covered with mucus, in which folds or wrinkles develop during manipulation with the electrocautery snare, are typically hyperplastic polyps or serrated adenomas that should be removed ( Fig. 1 ) . Ruddy, pedunculated polyps are most often adenomas, although juvenile polyps and Peutz-Jeghers polyps can have the same appearance. Mucosal prolapse in the sigmoid colon also can be confused with a pedunculated adenoma. Polyps with exudate on the surface are typically inflammatory, although juvenile polyps may have exudate, and some larger pedunculated adenomas have a superficial exudate. Superficial ulceration of an otherwise obvious sessile adenoma indicates the presence of cancer or high-grade dysplasia. Endoscopic resection should typically not be pursued unless the polyp appears benign or can be fully lifted with submucosal injection.

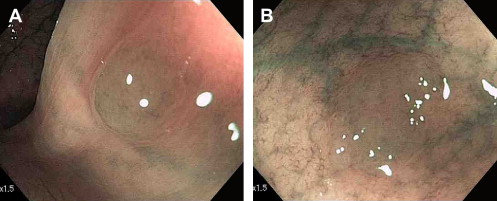

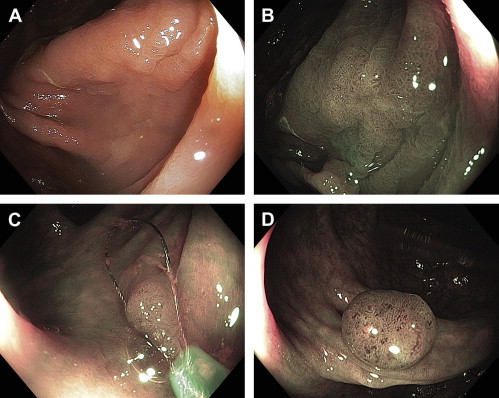

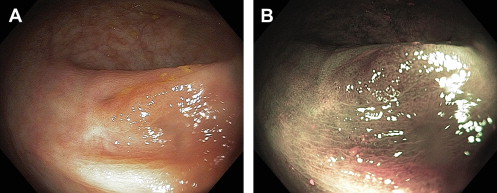

White-light clues to histology are insufficient to accurately determine whether resection is necessary. A reliable way of determining histology is by pit pattern analysis, first described by Professor Kudo and colleagues in Japan. Polyps with type I and II pits are hyperplastic ( Fig. 2 ), whereas types III through VI are neoplastic ( Fig. 3 ). The critical differentiation is between hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps. Most adenomas have type IIIL or IV pits. The great majority of studies of pit pattern have used high magnification colonoscopes, which are seldom available in the United States. High magnification is typically combined with chromoendoscopy or narrow band imaging (NBI) to clearly define the pit pattern . NBI also permits display of microcapillaries on the polyp surface, which can reliably differentiate adenomas. In NBI, adenomas appear browner than hyperplastic polyps because of their large numbers of microcapillaries and their tufted vascular pattern ( Fig. 4 ) . The accuracy of NBI using standard and high-definition colonoscopes without optical zoom functions, as currently available in the United States, has not been defined.

Other techniques that are not widely available but can allow accurate real-time histologic evaluation of colon polyps include autofluorescence and confocal laser microscopy. Autofluorescence is rarely used in the United States. It is based on the observation that autofluorescence patterns of dysplastic tissue, including adenomas, are different than those of normal tissue or hyperplastic polyps . Confocal laser microscopy is now available in commercial colonoscopes. It has been highly accurate in skilled hands in determining the real-time histology of colonic polyps . The level of training required for confocal laser microscopy and its practicality for routine use remain to be determined.

Small Polyp Removal

Despite the frequency of polypectomy, there are few data on the techniques of polypectomy to most effectively remove polyps and minimize complications. The most serious complication of polypectomy is perforation, and most colonoscopic perforations are polypectomy-related . Nearly all polypectomy-related perforations seem to result from electrocautery, but electrocautery is unnecessary to remove many small (<1 cm) polyps . Most polypectomy complications result from removal of small polyps because these polyps are so numerous (80% ≤5 mm in size and 90% ≤9 mm in size). The best approach to polypectomy in small polyps is therefore important.

Given the paucity of data from randomized controlled trials and the absence of formal recommendations regarding polypectomy techniques, it is not surprising that polypectomy techniques across the United States are inconsistent. In a survey of American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) members ( Table 1 ) , forceps methods were most often used to remove polyps 1 to 3 mm in size, including cold forceps in 50% of cases. For the 4- to 6-mm size range, no method was found to be predominant (see Table 1 ). For polyps 7 to 9 mm in size, the most commonly used modality was hot snaring, but a small number of physicians used hot forceps. An American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) position statement recommends that hot forceps should be used only for polyps 5 mm or smaller . Both hot and cold forceps techniques for larger polyps are associated with ineffective (incomplete) polypectomy .

| Number (%) of physicians reporting this method stratified according to polyp size | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Method | 1–3 mm polyp | 4–6 mm polyp | 7–9 mm polyp |

| Cold forceps | 95 (50.3) | 35 (18.5) | 4 (2.1) |

| Hot forceps | 63 (33.3) | 40 (21.2) | 8 (4.2) |

| Hot snare | 9 (4.8) | 59 (31.2) | 151 (79.9) |

| Cold snare | 9 (4.8) | 28 (14.8) | 11 (5.8) |

| Combined methods | 13 (6.9) | 27 (14.4) | 15 (7.8) |

Forceps have the advantage of being easier to place on very small flat polyps as compared with snares. Cold forceps are appropriate for 1- to 3-mm polyps, particularly if they engulf the polyp in one piece. Jumbo or large-capacity forceps are useful to engulf slightly larger polyps. Cold forceps are devoid of complication risks and can be safely used to resect diminutive polyps in patients who are therapeutically anticoagulated. The primary disadvantage of forceps techniques, whether hot or cold, is the possibility of leaving residual polyp behind . This risk almost certainly increases with increasing polyp size. With cold forceps this results from the requirement for a piecemeal technique, which may leave residual polyp and may obscure the exact margins of the polyp as the endoscopic field of view becomes bloodied after repeated biopsy.

The correct sequential technique for hot forceps is to grasp the tip of the polyp, tent or lift it, deflate the lumen, and apply electrocautery. Electrocautery spreads into the polyp and destroys it while preserving the portion in the forceps for pathologic examination. Although hot forceps are easy to apply, the electrocautery burn sometimes develops asymmetrically, resulting in coagulation of normal tissue. In addition, it is impossible to determine whether the central portion of the polyp has been destroyed. In two series of hot-forceps polypectomies, residual polyp was subsequently identified at the site in 16% to 28% of cases . There has been anecdotal evidence suggesting a higher incidence of postpolypectomy bleeding with hot forceps , but there is no controlled evidence yet to support or refute this notion. We no longer use hot forceps under any circumstances; however, it is apparent from the aforementioned survey that their use remains within the standard of medical care. Hot forceps polypectomy has limited effectiveness , and its use should be restricted to polyps 5 mm or smaller.

Both hot and cold snaring are more effective than forceps techniques to completely remove polyps . It is unknown whether a large study would demonstrate that hot snaring is slightly more effective than cold snaring in completely removing small polyps. One obvious benefit of cold snaring, however, is elimination of cautery-related complications . The development of diminutive snares has made snaring 1- to 5-mm polyps relatively simple in most cases.

Polyp shape and size are important considerations in deciding whether cold- versus hot-snare polypectomy is appropriate. Cold snaring has been shown to be safe and effective for polyps up to 7 mm in size . During cold-snare polypectomy, the authors’ practice is to attempt to ensnare a 1- to 2-mm rim of normal tissue around the polyp edge ( Fig. 5 ). This technique is inadvisable when using snare electrocautery, because it increases the size of the cautery burn. We typically do not tent during cold-snare removal because this may cause the polyp to pop out of the endoscopic field of view immediately after transection. If the polyp is not tented, it almost invariably remains on or near the site after transection for easy retrieval . We typically use cold snaring on pedunculated polyps up to 4 to 5 mm in size, and on bulky or dome-shaped sessile polyps up to about the same size. We use cold snaring for flat polyps up to 7 to 10 mm in size, occasionally using a piecemeal cold snaring technique. For hot-snare polypectomy of polyps less than 1 cm, tenting the lesion and deflating the lumen are advised to protect the muscularis propria from cautery injury.

There is currently no standard of care with regard to the type of current used for polypectomy. The survey of ACG members on polypectomy revealed that 46% of respondents used pure low-power coagulation, 46% used blended current, and 3% used cutting current . Low-power coagulation is associated with a lower risk for immediate bleeding but a higher risk for delayed bleeding . Contrariwise, cutting or blended current is more likely to be associated with immediate bleeding than delayed bleeding. Because the endoscopist may control immediate bleeding during the procedure, blended or cutting current seems advantageous. Both types of current are presently considered acceptable, however.

Small Polyp Removal

Despite the frequency of polypectomy, there are few data on the techniques of polypectomy to most effectively remove polyps and minimize complications. The most serious complication of polypectomy is perforation, and most colonoscopic perforations are polypectomy-related . Nearly all polypectomy-related perforations seem to result from electrocautery, but electrocautery is unnecessary to remove many small (<1 cm) polyps . Most polypectomy complications result from removal of small polyps because these polyps are so numerous (80% ≤5 mm in size and 90% ≤9 mm in size). The best approach to polypectomy in small polyps is therefore important.

Given the paucity of data from randomized controlled trials and the absence of formal recommendations regarding polypectomy techniques, it is not surprising that polypectomy techniques across the United States are inconsistent. In a survey of American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) members ( Table 1 ) , forceps methods were most often used to remove polyps 1 to 3 mm in size, including cold forceps in 50% of cases. For the 4- to 6-mm size range, no method was found to be predominant (see Table 1 ). For polyps 7 to 9 mm in size, the most commonly used modality was hot snaring, but a small number of physicians used hot forceps. An American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) position statement recommends that hot forceps should be used only for polyps 5 mm or smaller . Both hot and cold forceps techniques for larger polyps are associated with ineffective (incomplete) polypectomy .

| Number (%) of physicians reporting this method stratified according to polyp size | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Method | 1–3 mm polyp | 4–6 mm polyp | 7–9 mm polyp |

| Cold forceps | 95 (50.3) | 35 (18.5) | 4 (2.1) |

| Hot forceps | 63 (33.3) | 40 (21.2) | 8 (4.2) |

| Hot snare | 9 (4.8) | 59 (31.2) | 151 (79.9) |

| Cold snare | 9 (4.8) | 28 (14.8) | 11 (5.8) |

| Combined methods | 13 (6.9) | 27 (14.4) | 15 (7.8) |

Forceps have the advantage of being easier to place on very small flat polyps as compared with snares. Cold forceps are appropriate for 1- to 3-mm polyps, particularly if they engulf the polyp in one piece. Jumbo or large-capacity forceps are useful to engulf slightly larger polyps. Cold forceps are devoid of complication risks and can be safely used to resect diminutive polyps in patients who are therapeutically anticoagulated. The primary disadvantage of forceps techniques, whether hot or cold, is the possibility of leaving residual polyp behind . This risk almost certainly increases with increasing polyp size. With cold forceps this results from the requirement for a piecemeal technique, which may leave residual polyp and may obscure the exact margins of the polyp as the endoscopic field of view becomes bloodied after repeated biopsy.

The correct sequential technique for hot forceps is to grasp the tip of the polyp, tent or lift it, deflate the lumen, and apply electrocautery. Electrocautery spreads into the polyp and destroys it while preserving the portion in the forceps for pathologic examination. Although hot forceps are easy to apply, the electrocautery burn sometimes develops asymmetrically, resulting in coagulation of normal tissue. In addition, it is impossible to determine whether the central portion of the polyp has been destroyed. In two series of hot-forceps polypectomies, residual polyp was subsequently identified at the site in 16% to 28% of cases . There has been anecdotal evidence suggesting a higher incidence of postpolypectomy bleeding with hot forceps , but there is no controlled evidence yet to support or refute this notion. We no longer use hot forceps under any circumstances; however, it is apparent from the aforementioned survey that their use remains within the standard of medical care. Hot forceps polypectomy has limited effectiveness , and its use should be restricted to polyps 5 mm or smaller.

Both hot and cold snaring are more effective than forceps techniques to completely remove polyps . It is unknown whether a large study would demonstrate that hot snaring is slightly more effective than cold snaring in completely removing small polyps. One obvious benefit of cold snaring, however, is elimination of cautery-related complications . The development of diminutive snares has made snaring 1- to 5-mm polyps relatively simple in most cases.

Polyp shape and size are important considerations in deciding whether cold- versus hot-snare polypectomy is appropriate. Cold snaring has been shown to be safe and effective for polyps up to 7 mm in size . During cold-snare polypectomy, the authors’ practice is to attempt to ensnare a 1- to 2-mm rim of normal tissue around the polyp edge ( Fig. 5 ). This technique is inadvisable when using snare electrocautery, because it increases the size of the cautery burn. We typically do not tent during cold-snare removal because this may cause the polyp to pop out of the endoscopic field of view immediately after transection. If the polyp is not tented, it almost invariably remains on or near the site after transection for easy retrieval . We typically use cold snaring on pedunculated polyps up to 4 to 5 mm in size, and on bulky or dome-shaped sessile polyps up to about the same size. We use cold snaring for flat polyps up to 7 to 10 mm in size, occasionally using a piecemeal cold snaring technique. For hot-snare polypectomy of polyps less than 1 cm, tenting the lesion and deflating the lumen are advised to protect the muscularis propria from cautery injury.

There is currently no standard of care with regard to the type of current used for polypectomy. The survey of ACG members on polypectomy revealed that 46% of respondents used pure low-power coagulation, 46% used blended current, and 3% used cutting current . Low-power coagulation is associated with a lower risk for immediate bleeding but a higher risk for delayed bleeding . Contrariwise, cutting or blended current is more likely to be associated with immediate bleeding than delayed bleeding. Because the endoscopist may control immediate bleeding during the procedure, blended or cutting current seems advantageous. Both types of current are presently considered acceptable, however.

Large Pedunculated Polyps

Large pedunculated adenomas are most common in the sigmoid colon. Pedunculated mucosal prolapse in the sigmoid is sometimes confused with an adenoma, but can be distinguished by the punctate (rather than uniform) erythema on the surface of the prolapsing tissue, the gradual transition from erythema to normal-colored mucosa and the normal pit pattern of the mucosa . Lipomas can also be confused with adenomas if they exhibit erythema on their surface from prolapse. Of note, lipomas should not be removed endoscopically, unless symptomatic, because of an increased risk for perforation.

The authors’ practice is to remove large pedunculated polyps without pretreatment to reduce the risk for bleeding. Most endoscopists who use cutting or blended current prefer pretreatment to prevent immediate bleeding. A commonly recommended approach is to consider pretreatment for patients who have polyps with a stalk thicker than 1 cm, because such stalks can contain a substantial artery . Pretreatment by injection of the stalk with epinephrine in saline has proved to prevent immediate, but not delayed, bleeding in randomized controlled trials . It is unclear whether this effect is from local tamponade or the vasoconstrictive effects of epinephrine. In the previously cited survey of ACG members, preinjection with epinephrine was the most commonly used method to prevent bleeding from large pedunculated polyps . In two randomized, controlled trials, detachable snares were found to be effective in the prevention of bleeding in pedunculated polyps 1 cm or larger . The risk for bleeding from pedunculated polyps is low, however , and some endoscopists reserve the use of detachable snares for patients who are considered high risk, such as those who must resume anticoagulation shortly after polypectomy. Detachable snares have been associated with complications, including pedicle transection from overtightening and inadequate tightening . If used for polyps with a short stalk, a detachable snare may slip off, resulting in massive bleeding .

When removing pedunculated polyps, the electrocautery snare should be placed between one third to one half the distance from the base of the polyp head to the colonic wall to leave residual stalk after resection that can be grabbed if immediate bleeding occurs. Removing some stalk with the polyp increases the likelihood that if cancer is found in the polyp head, the resection line will be free of cancer. Very large snares are useful for very large pedunculated polyps. Polyps in the sigmoid colon are often best approached by opening the snare with the colonoscope tip proximal to the polyp and then withdrawing the colonoscope. If the polyp is in an awkward position, repositioning the patient may make the polyp more accessible. It is sometimes impossible to remove a large pedunculated polyp en bloc, so piecemeal removal must instead be performed. This approach is acceptable, but the portion of the polyp nearest the stalk or colonic wall should be separately submitted to pathology because this section is most important with regard to whether cancer is present.

Immediate postpolypectomy bleeding is managed in several ways. First, traditional management includes regrasping the stalk and holding it for 10 to 15 minutes. It is inadvisable to retransect the stalk with electrocautery, because this might leave no residual stalk to grasp if bleeding continues. Injection of epinephrine or application of multipolar electrocautery may be used to manage bleeding from a polypectomy stalk. Detachable snares can be used after hemostasis has been achieved, but it is impractical to place a detachable snare on the polypectomy stalk after transection in the presence of brisk bleeding. Clips have been clearly effective in arresting immediate postpolypectomy hemorrhage and delayed bleeding when applied to visible vessels in either sessile or pedunculated polyps . Clips were ineffective in preventing postpolypectomy hemorrhage after endoscopic polypectomy in a randomized controlled trial that included primarily small polyps at low risk for bleeding . Further study is needed regarding whether prophylactic clipping is effective when a high risk for postpolypectomy bleeding is present. In an uncontrolled series, prophylactic clipping was associated with no subsequent hemorrhage when polypectomy with electrocautery was used to resect polyps 1 cm or smaller .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree