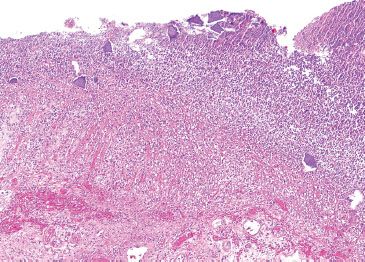

Figure 4.1 Normal colon. This resection specimen illustrates the four main layers of the colon: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa. The mucosa consists of epithelium (E), lamina propria (L), and muscularis mucosae (MM). The submucosa sits between the muscularis mucosae and the muscularis propria, and it consists of loose fibroconnective tissue and lymphovascular channels. The muscularis propria consists of inner circular and outer longitudinally orientated muscle fibers. This is covered by subserosal fibroadipose tissue and the outermost serosa.

Figure 4.2 Test tubes in a rack, profile view. Normal colonic architecture is analogous to a profile view of test tubes in a rack, with each test tube (or crypt) superimposable upon its neighbor based on uniform size and distribution.

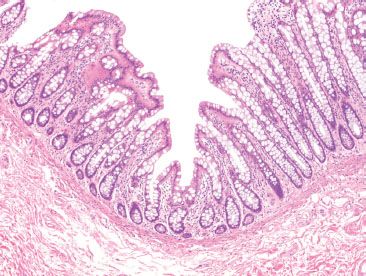

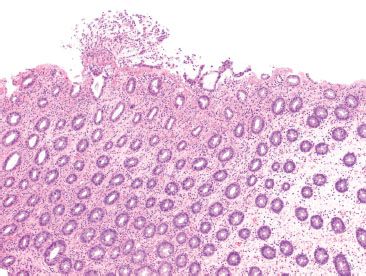

Figure 4.3 Normal colon. A well-oriented colonic section illustrates the orderly nature of the colonic crypts. They are evenly spaced and arranged in parallel, like a row of test tubes in a rack. The crypt bases extend down to almost touch the muscularis mucosae.

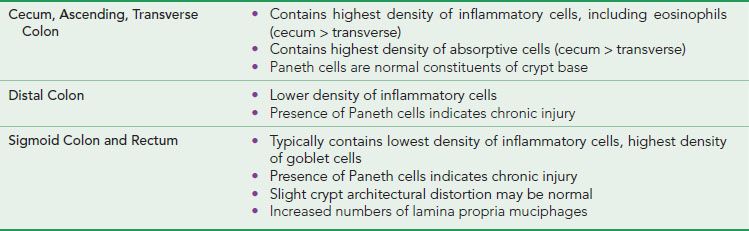

Similarly, the contents of the colonic lamina propria vary depending on location. This supportive stroma contains a wide variety of cells arranged among loosely organized strands of collagen, occasional slips of smooth muscle, nerve twiglets, and small lymphovascular spaces that lack the potential for lymphovascular spread of tumor.1 The cellular composition is predominantly lymphocytic and plasmacytic, with varying numbers of eosinophils and mast cells. This normal complement of inflammatory cells decreases in concentration approaching the rectum; knowledge of this prevents overdiagnosis of “chronic colitis” (Figs. 4.10–4.13). See also Chronic Colitis, this chapter. A rare neutrophil in the lamina propria or capillary vessel is likely insignificant. The right colon contains more absorptive cells and fewer goblet cells than the left colon, a reflection of the differing functions of the right colon (to absorb excess fluid) versus the left colon (to lubricate the lumen and facilitate elimination of the luminal contents). Muciphages, while not native inhabitants, are so commonly found in the rectum that they are considered by many as normal variants. These colonic macrophages contain abundant cytoplasmic mucin from “clean up” of nonspecific mucosal injury (Figs. 4.14 and 4.15)2; when excessive, one might consider pathologic entities such as metabolic storage disorders or infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare. See also Muciphages, Near Misses, this chapter.

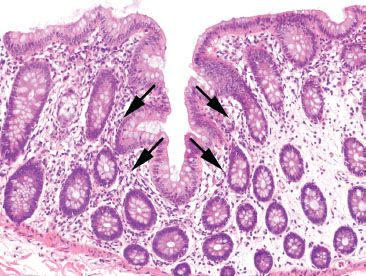

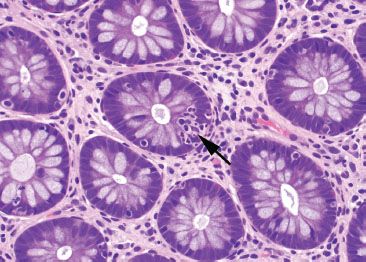

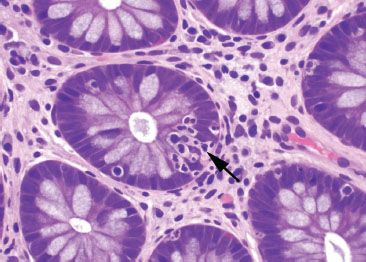

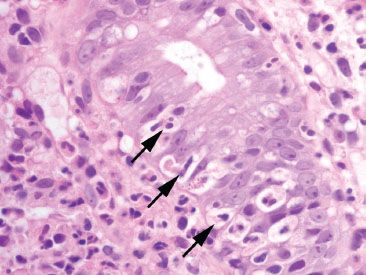

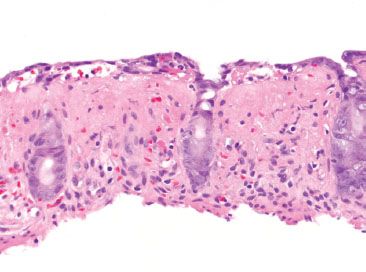

Figure 4.4 Normal colon. An innominate groove in the colon shows crypts branching from a central lumen (arrows). This is a normal structure in the colon and should not be mistaken for the crypt distortion seen in chronic colitis.

Figure 4.5 Normal colon. An innominate groove in the colon shows crypts extending away from a central lumen in an orderly and symmetric fashion. Note that the background crypts are evenly spaced, indicating a lack of chronic injury (chronicity). This normal structure, seen periodically along the length of the colonic mucosa, should not be mistaken for the crypt branching of chronic colitis.

Figure 4.6 Test tubes in a rack, tangential view. When viewed from above, the test tubes are superimposable upon their neighbors based on uniform size and distribution, analogous to a tangential view of normal colonic architecture.

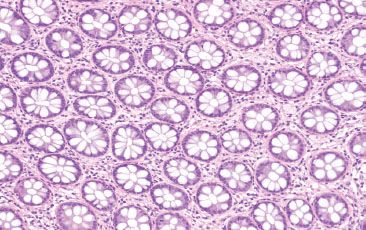

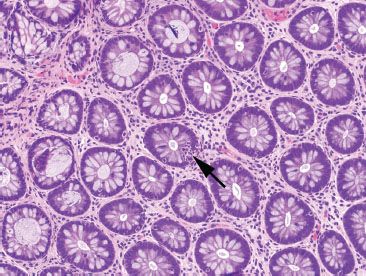

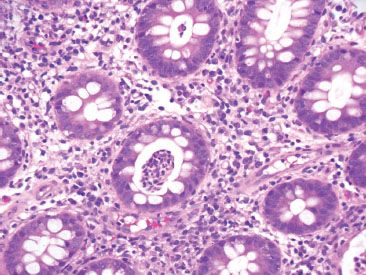

Figure 4.7 Normal colon. When cut in cross section, the colonic crypts appear like an evenly spaced bed of flowers. Even when maloriented, or tangentially sectioned, the normal colonic mucosa shows an orderly distribution of colonic crypts.

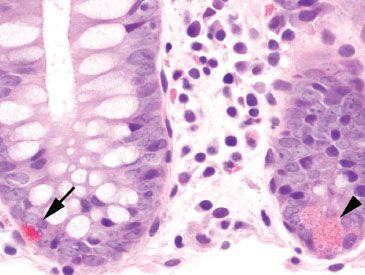

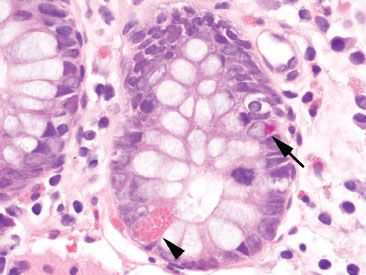

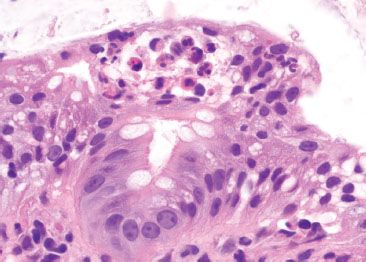

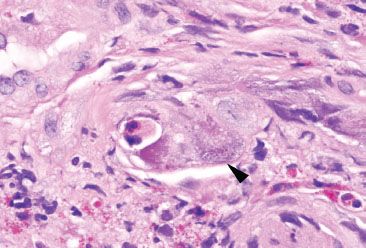

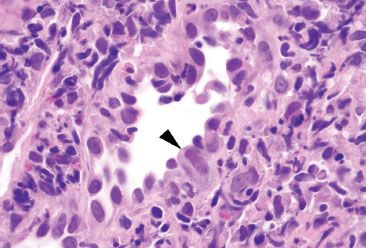

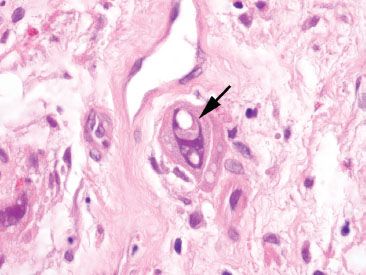

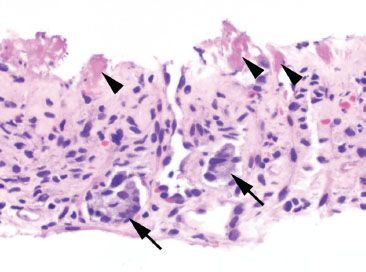

Figure 4.8 Normal colon, Paneth cell versus endocrine cell. Paneth cells (arrowhead) are found in the crypt bases of the right and transverse colon. Their nuclei abut the basement membrane, while their coarse, pink cytoplasmic granules polarize toward the crypt lumen. By comparison, endocrine cells (arrow) are found scattered throughout the crypt bases along the length of the colon. Their nuclei face the lumen, while their fine, reddish cytoplasmic granules abut the basement membrane.

Figure 4.9 Normal colon, Paneth cell versus endocrine cell. The Paneth cell (arrowhead) contains larger, coarse, pink granules released toward the crypt lumen, whereas the endocrine cell (arrow) contains small, fine, reddish granules released toward the crypt basement membrane. Paneth cells in the left colon signify evidence of chronic injury.

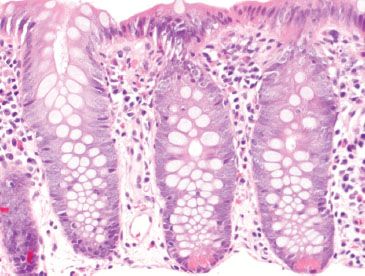

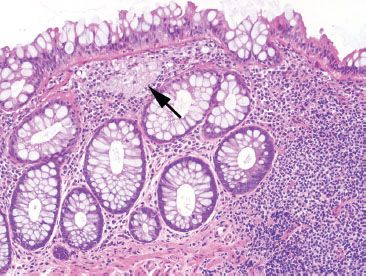

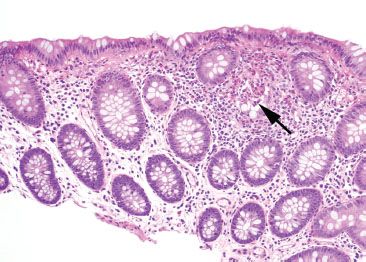

Figure 4.10 Normal right colon. The right colon is rich in Paneth cells at the crypt bases. In addition, mixed chronic inflammatory cells are abundant in the lamina propria, including scattered eosinophils.

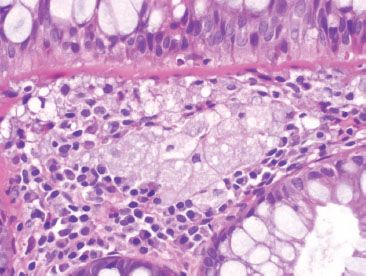

Figure 4.11 Normal right colon. The lamina propria of the right colon contains substantial numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils.

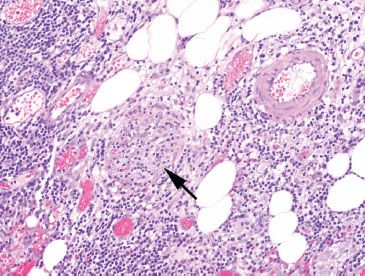

The cellular composition of the submucosa is similar to that of the lamina propria, but includes larger lymphovascular structures that, in contrast to those of the lamina propria, can facilitate lymphovascular spread of tumor cells. Other submucosal cells include adipocytes, ganglion cells, and nerve axons, the latter two of which compose the superficial Meissner plexus and the deeper Henle’s plexus. These ganglion cells are not normally present in the mucosa, and when found there indicate prior mucosal injury.

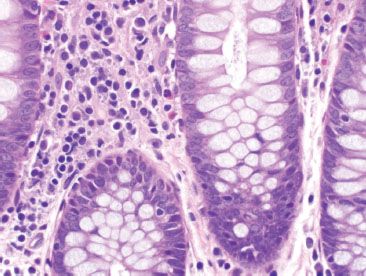

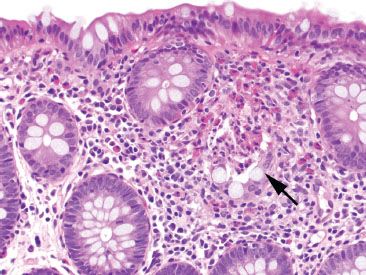

Figure 4.12 Normal left colon. Compared to the right colon (Figs. 4.10 and 4.11), the normal left colon contains fewer lamina propria inflammatory cells. Although eosinophils may be present in the left colon, they are far less common as compared to the right colon. Note, also, the lack of Paneth cells at the crypt bases.

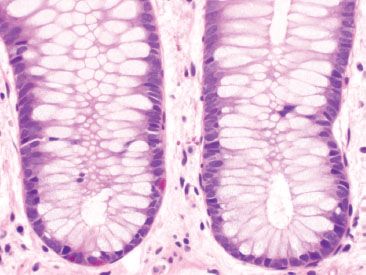

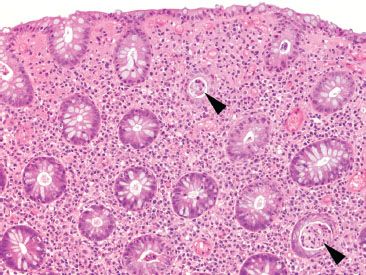

Figure 4.13 Normal rectum. The rectal lamina propria is paucicellular and more goblet cells are seen compared to their density in proximal sites. Red-colored endocrine cells are normally present throughout the colon, but note the absence of Paneth cells in the crypt bases.

Figure 4.14 Near-normal rectum, muciphages in the rectum. Muciphages (arrow) may cluster or can be found dispersed singly in the lamina propria, particularly in the rectum. They are a nonspecific sign of mucosal injury.

Figure 4.15 Near-normal rectum. Higher magnification of previous figure shows the amphophilic and bubbly cytoplasm of the muciphages.

The muscularis propria surrounds the submucosa with its inner circular and outer longitudinal layers of smooth muscle, which sandwich the myenteric plexus of Auerbach. Externally, the subserosal connective tissue and the mesothelial-derived serosa encase the bowel. Sites not entirely covered by serosa include the posterior surface of the ascending and descending colon and portions of the rectum (posterior aspect of the upper third, posterior and lateral aspects of the middle third, and the entire lower third), features important for assessing radial margins in resection specimens of colonic neoplasms. Grossly visible through the serosa are the external longitudinal layers of the muscularis propria, which appear as three distinct bands, or taenia coli, on the right colon and become confluent on the left.

TABLE 4.1: Distinctive Differences among Regions of the Large Bowel

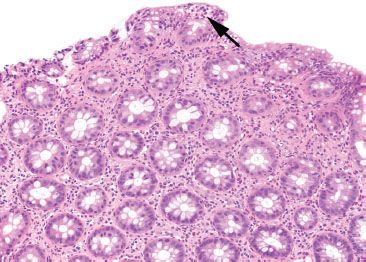

FOCAL ACTIVE COLITIS PATTERN

Figure 4.16 Focal active colitis pattern. Except for an isolated collection of neutrophils invading the crypt epithelium (arrow), this colonic biopsy appears essentially normal; the background crypts are evenly spaced and orderly.

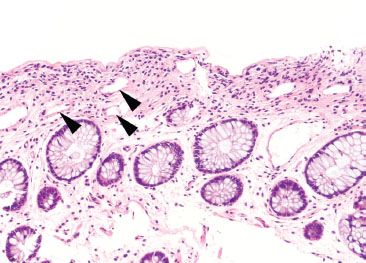

Focal active colitis (FAC) is a histologic pattern characterized by single foci of neutrophilic crypt injury without features of chronic injury (chronicity) (Figs. 4.16–4.23). The pattern encompasses a spectrum of histologic changes, ranging from a single crypt abscess (neutrophils in the crypt lumen) and single focus of cryptitis (neutrophils in the crypt epithelium) to multiple discrete foci of cryptitis, or even crypt abscesses within a series of colorectal biopsies.3 Segmental distribution and features of architectural distortion and chronicity are absent, by definition. Similar to most patterns, the FAC pattern does not represent a discrete disease entity, but instead represents multiple clinical prodromes that have similar histologic features. These include acute self-limited colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, bowel preparation artifact, antibiotic-associated colitis (i.e., Clostridium difficile colitis), and medication injury (i.e., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs). Among these patients, clinically significant diarrhea is the most common indication for colonoscopy; however, FAC is also an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients undergoing routine cancer surveillance colonoscopy. As a result, determining the significance of FAC requires correlation with clinical and microbiologic information.

Figure 4.17 Focal active colitis pattern. Higher magnification of the previous case shows evenly spaced and orderly crypt architecture and an isolated focus of acute inflammation in the epithelium (cryptitis) (arrow).

Figure 4.18 Focal active colitis pattern. Higher magnification of the previous case shows the single focus of cryptitis (arrow). The surrounding crypts are unaffected.

Figure 4.19 Focal active colitis pattern. This low magnification emphasizes the orderly architecture of the colonic crypts. Cut in cross section, they appear like an evenly spaced bed of flowers. A single isolated focus of acute inflammation (arrow) is present at the surface.

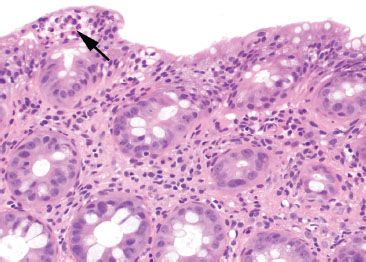

Figure 4.20 Focal active colitis pattern. Higher magnification of the previous case shows an isolated focus of acute inflammation (arrow) in a background of unremarkable colonic mucosa.

Figure 4.21 Focal active colitis pattern. Higher magnification of the previous case shows a small neutrophilic abscess at the colonic surface.

Figure 4.22 Focal active colitis pattern. The low-magnification photo emphasizes the focality of the changes in this biopsy. The background colonic crypts are evenly spaced, and only a single, isolated focus of acute inflammation (arrow) is present.

Figure 4.23 Focal active colitis pattern. Higher magnification of the previous case reveals an isolated crypt abscess with neutrophils and eosinophils in the crypt lumen (arrow).

PEARLS & PITFALLS

A diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may be rendered if additional histologic features, such as mucosal distortion, chronic inflammation of the lamina propria, or epithelioid granulomas are present.4 Often, however, these additional features are insufficiently developed to establish a clear-cut diagnosis of IBD. Although FAC may be a harbinger to IBD, especially in children, there is a preponderance of acute self-limited colitis, antibiotic-associated colitis, and medication injury among these patients.

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the FAC Pattern

Acute Self-limited Colitis

Acute Self-limited Colitis

Infection

Infection

Medication

Medication

Chemicals or Irritants

Chemicals or Irritants

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Ischemic Colitis

Ischemic Colitis

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Antibiotic-Associated Colitis (Clostridium difficile Colitis)

Antibiotic-Associated Colitis (Clostridium difficile Colitis)

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Bowel Preparatory Artifact

Bowel Preparatory Artifact

ACUTE SELF-LIMITED COLITIS

By definition, acute self-limited colitis is one that resolves in less than 4 weeks. An identifiable infectious agent is found in approximately half of cases, the most common pathogens of which are Campylobacter jejunales, Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia. Clinical clues favoring infectious colitis include acute onset, fever within the first week of disease onset, and at least 10 bowel movements in a 24-hour period. By contrast, the majority of patients eventually diagnosed with IBD have a more insidious onset, lack a fever within the first week of onset, and have no more than six bowel movements in a 24-hour period. The remaining cases of acute self-limited colitis for which stool cultures are negative are the result of viral infection, parasitic infection, medication reaction, or other chemical irritants. Histologically, biopsies show a predominantly acute inflammation restricted to the mucosa in either a patchy or diffuse fashion. Erosions, ulcerations, and neutrophilic involvement of crypt epithelium (cryptitis) and crypt lumens (crypt abscesses) may be seen, but features of chronicity (e.g., crypt distortion, crypt dropout, crypt shortfall, increased lamina propria chronic inflammation) are absent.

KEY FEATURES of the Focal Active Colitis Pattern:

• FAC refers to individual foci of neutrophilic inflammation in the absence of chronicity.

• The most common etiology is acute self-limited colitis.

• Acute self-limited colitis is defined as a diarrheal illness less than 4 weeks in duration, and is most commonly attributed to infection even though half of these patients have negative stool cultures.

• Other associations with FAC include inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, antibiotic-associated colitis, and NSAIDs.

• FAC in asymptomatic patients undergoing surveillance endoscopy is likely of no clinical significance and may be related to bowel preparation artifact.

ACUTE COLITIS PATTERN

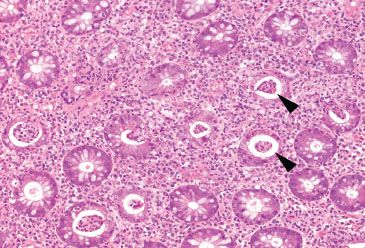

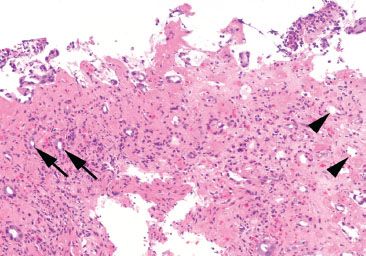

Figure 4.24 Acute colitis pattern. Low magnification reveals abundant crypt abscesses (arrowheads) in a background of preserved crypt architecture. By definition, acute colitis lacks features of chronic injury (chronicity).

Acute colitis describes an injury pattern similar to FAC, but more severe or diffuse, the features of which include cryptitis (acute inflammation in the crypt epithelium) (Figs. 4.24 and 4.25), crypt abscesses (acute inflammation in the crypt lumina) (Fig. 4.26), erosions, and ulcerations in the absence of chronicity. This pattern of injury is entirely nonspecific, but is most commonly caused by acute viral and bacterial infections, medications (NSAIDs, Kayexalate, sevelamer, ipilimumab, etc.) and emerging or partially treated inflammatory bowel disease. Although ancillary findings of lamina propria hemorrhage or fibrin deposition may be seen in acute colitis pattern, the distinctive findings of microcrypts or pseudomembranes raise a unique set of differential diagnoses, and are therefore discussed as separate patterns within this chapter. See also Ischemic Colitis Pattern and Pseudomembranous Pattern, this chapter.

Figure 4.25 Acute colitis pattern, cryptitis. Neutrophils cross the basement membrane and infiltrate the crypt epithelium (arrows).

Figure 4.26 Acute colitis pattern, crypt abscess. An aggregate of neutrophils fills a crypt lumen, forming a crypt abscess.

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Acute Colitis Pattern

Infection (Cytomegalovirus, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter)

Infection (Cytomegalovirus, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter)

Medication (NSAIDs, Kayexalate, sevelamer, ipilimumab)

Medication (NSAIDs, Kayexalate, sevelamer, ipilimumab)

Inflammatory Bowel Disease, emerging or partially treated

Inflammatory Bowel Disease, emerging or partially treated

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

KEY FEATURES of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Colitis:

• CMV colitis is most frequently seen among immunocompromised patients, transplant patients, and the elderly.

• Endothelial cells, macrophages, and stromal cells are preferentially affected by CMV, although epithelial involvement is common (Figs. 4.27–4.30)

• The viral cytopathic effect is characterized by cytomegaly (cell enlargement) containing both nuclear (“owl’s eye”) and cytoplasmic inclusion bodies that have a distinctive magenta tinctorial quality (Figs. 4.31–4.34)

• An inflammatory backdrop of mononuclear cells often accompanies the acute colitis (Figs. 4.35 and 4.36)

• Biopsies of the ulcer base are most likely to yield diagnostic CMV viral cytopathic effect.

• CMV immunostains are not necessary if classic viral cytopathic effect is seen on H&E.

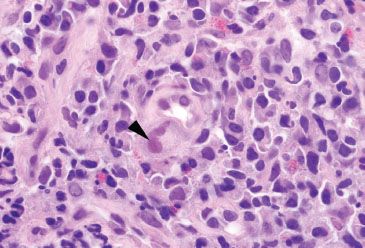

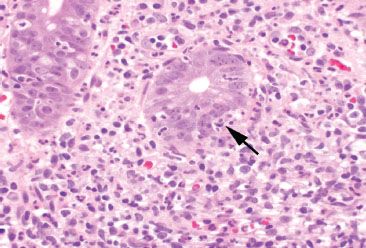

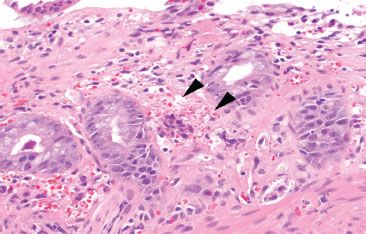

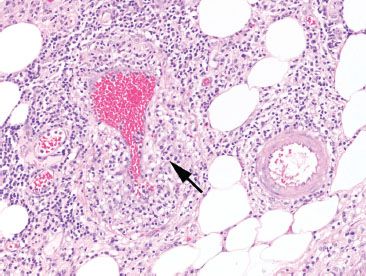

Figure 4.27 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. This infected endothelial cell (arrowhead) bulges into the lumen of a small vascular space. This markedly enlarged cell is easy to spot, even at low magnification.

Figure 4.28 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. This small vessel shows abnormal hobnail-like endothelial cells. One cell shows characteristic enlargement with both nuclear and cytoplasmic expansion (arrowhead). Note the tinctorial change in this CMV infected cell.

Figure 4.29 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. CMV preferentially infects endothelial cells. This small capillary shows a markedly enlarged endothelial cell with nuclear inclusions (arrowhead) characteristic of CMV. Note the mononuclear cell infiltrate in the background.

Figure 4.30 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. The enlarged nucleus in this infected endothelial cell (arrowhead) shows the characteristic tinctorial change of CMV.

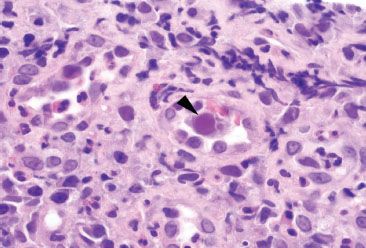

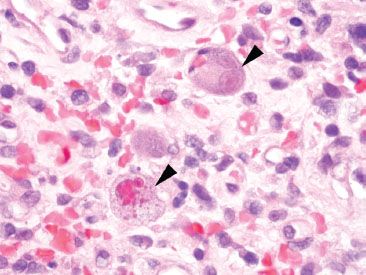

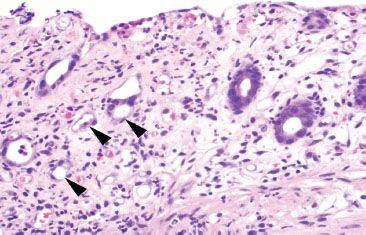

Figure 4.31 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. Viral cytopathic effect of CMV includes nuclear and cytoplasmic expansion resulting in cellular enlargement (“cytomegaly”), as well as both nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (arrowheads).

Figure 4.32 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. These enlarged cells (arrowheads) show characteristic inclusions of cytomegalovirus infection. Note the tinctorial quality of these infected cells.

Figure 4.33 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. Both cytoplasmic and nuclear inclusions are evident in these infected cells (arrowheads). The top right cell shows the characteristic “owl’s eye” nuclear inclusion of CMV.

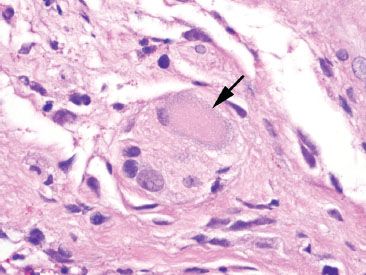

Figure 4.34 Ganglion cell. Ganglion cells (arrow) can be mistaken for CMV infected cells due to their amphophilic and voluminous cytoplasm. When in doubt, correlation with a CMV immunostain may be necessary.

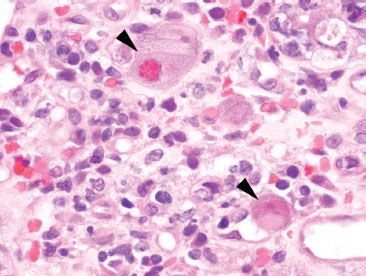

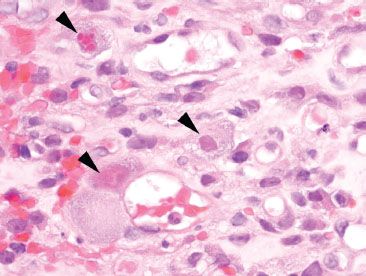

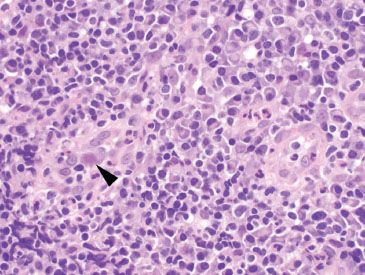

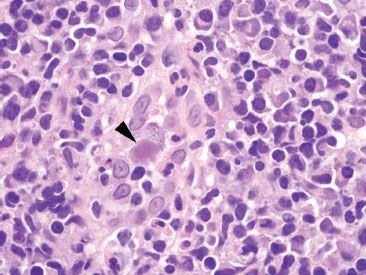

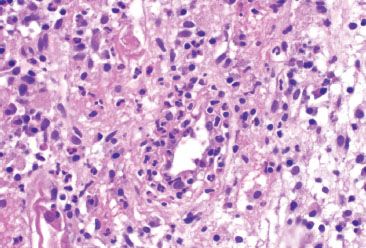

Figure 4.35 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. Although CMV infections (arrowhead) cause acute inflammation and ulceration of the mucosa, it can be accompanied by a prominent mononuclear backdrop, as seen here.

Figure 4.36 Acute colitis pattern, Cytomegalovirus. Higher magnification of the previous case shows a CMV infected cell (arrowhead) with a prominent mononuclear backdrop composed primarily of plasma cells and lymphocytes. Scattered neutrophils are also present.

SALMONELLA

KEY FEATURES of Salmonella Infection:

• Salmonella is a gram-negative bacteria transmitted through contaminated food (meat, dairy, eggs, produce) and water that can survive partial cooking, freezing, and drying.5

• Infection is divided into two groups:

(1) Typhoid serotypes include S. typhi and S. paratyphi.

(2) Nontyphoid serotypes include S. enteritidis, S. typhimurium, S. muenchen, S. Newport, and S. paratyphi, among others.5

• Clinical presentation of typhoid species includes fever, abdominal rash, hepatosplenomegaly, leukopenia, abdominal pain, headache, watery diarrhea that progresses to hematochezia, and perforation.

• Nontyphoid species cause less severe illness.

• Treatment is supportive care and antibiotics.

• Histologic features of typhoid fever include involvement of the ileum, right colon, and appendix with hyperplastic Peyer patches, deep ulceration, and necrosis (Figs. 4.37–4.41).

• Acute inflammation and a mononuclear backdrop are present.6,7

• Architectural distortion of crypts may raise the question of inflammatory bowel disease.

• Nontyphoid infection shows an acute colitis, but features can overlap with typhoid fever.8

• Culture is required for definitive diagnosis.

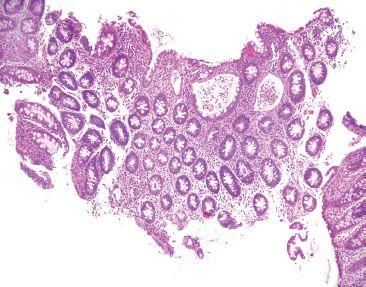

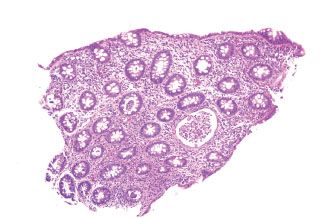

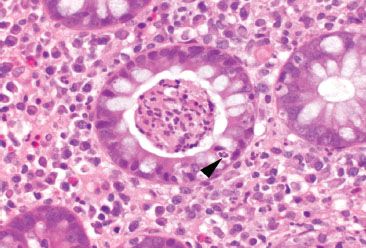

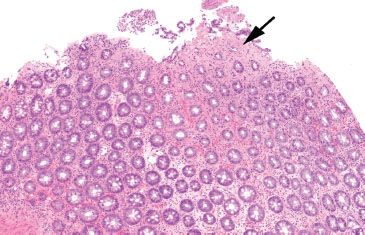

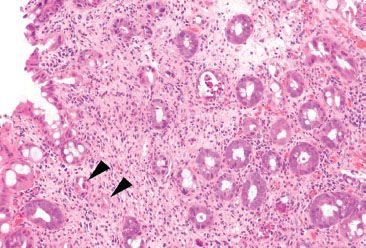

Figure 4.37 Acute colitis pattern, Salmonella infection. Scanning magnification shows an acute colitis with prominent crypt abscesses, but relatively preserved crypt architecture. Although slightly distorted due to the crypt abscesses, these cross-sectioned crypts look like an evenly spaced bed of flowers.

Figure 4.38 Acute colitis pattern, Salmonella infection. Again, note the relatively preserved crypt architecture as the backdrop to this acute colitis with abundant crypt abscesses.

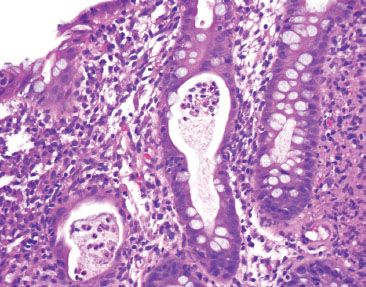

Figure 4.39 Acute colitis pattern, Salmonella infection. This biopsy shows multiple crypt abscesses and abundant acute inflammation, but no significant crypt architectural changes.

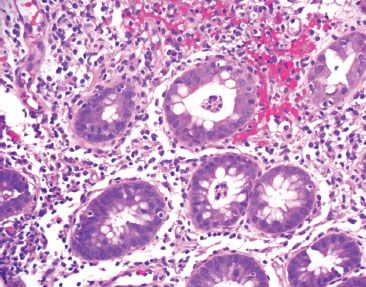

Figure 4.40 Acute colitis pattern, crypt abscess in Salmonella infection. Abundant neutrophils fill the crypt lumen.

Figure 4.41 Acute colitis pattern, Salmonella infection. Lamina propria hemorrhage and abundant cryptitis and crypt abscesses are present.

SHIGELLA

KEY FEATURES of Shigella Infection:

• Shigella is an invasive gram-negative bacillus and a major cause of diarrhea across the world.

• S. dysenteriae is the most virulent and most common, but S. sonnei and S. flexneri are increasingly reported in the United States.

• Shigella has the highest infectivity rate among all enteric gram-negative bacteria, with food- and water-borne transmission, as well as the fecal–oral route; rare instances of sexual transmission are also reported.

• Outbreaks are associated with crowded living conditions and poor sanitation, with children less than 6 years most commonly affected.

• Patients present with fever, abdominal pain, and watery diarrhea, followed by bloody diarrhea with mucus and pus.

• Onset of symptoms begins within 12 to 50 hours after ingestion of contaminated food or water.

• Medical complications are most commonly seen with S. dysenteriae, and include severe dehydration, sepsis, toxic megacolon and perforation. Autoimmune phenomena such as reactive arthritis, reactive arthropathy, and hemolytic–anemic syndrome also occur.9

• Treatment is supportive care and antibiotics.

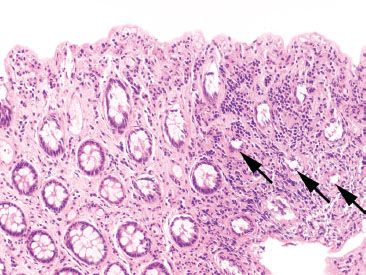

• Histologic findings include a left colon predominant acute colitis, sometimes with terminal ileum involvement.

• Early changes appear as a diffuse acute colitis, with or without pseudomembranes (Figs. 4.42–4.45).10

• Later changes may show patchy or segmental involvement, and concomitant architectural distortion may raise the question of inflammatory bowel disease.11

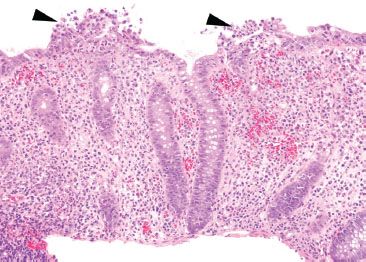

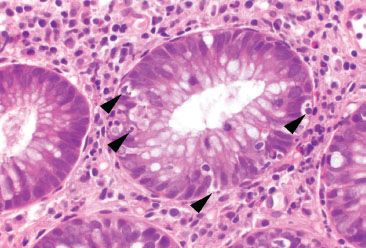

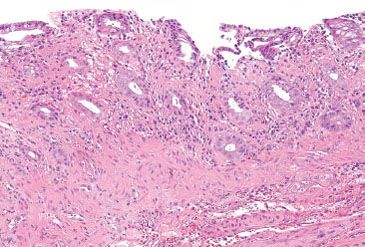

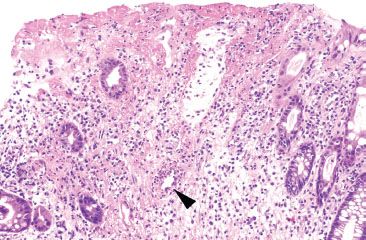

Figure 4.42 Acute colitis pattern, Shigella infection. At low magnification, the crypt architecture is relatively preserved. There is abundant acute inflammation involving both the crypts and the surface epithelium (arrowheads).

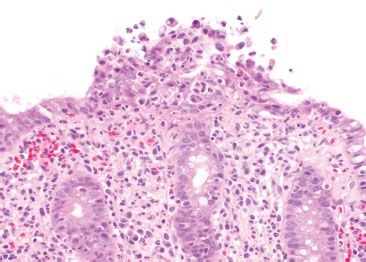

Figure 4.43 Acute colitis pattern, Shigella infection. Higher magnification of the previous case shows surface neutrophilic abscess.

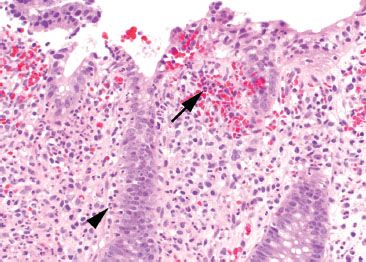

Figure 4.44 Acute colitis pattern, Shigella infection. Lamina propria hemorrhage (arrow) and abundant cryptitis (arrowhead) are present.

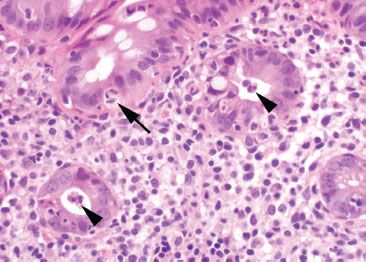

Figure 4.45 Acute colitis pattern, Shigella infection. Neutrophils are present within the colonic epithelium (arrow) and within the crypt lumen (arrowheads).

CAMPYLOBACTER

KEY FEATURES of Campylobacter Infection:

• Campylobacter is a gram-negative food and water-borne bacterium found in undercooked poultry, raw milk, and untreated water.12

• C. jejuni is most commonly associated with food-borne gastroenteritis, followed by C. coli and C. laridis.12–14

• Watery diarrhea is the most common presentation, accompanied by fever and cramping abdominal pain.12

• Infants, children, and young adults are most commonly affected, and there is a higher incidence in HIV-positive patients, particularly with C. fetus.12

• Autoimmune complications such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and reactive arthropathy are associated.12

• Treatment is supportive care, with resolution within 1 to 2 weeks. Antibiotics may be needed in immunocompromised patients, or those with severe, recurrent, or disseminated infection.15

• Histologic features include an acute colitis (Figs. 4.46–4.49) and stool culture is necessary for definitive diagnosis.15

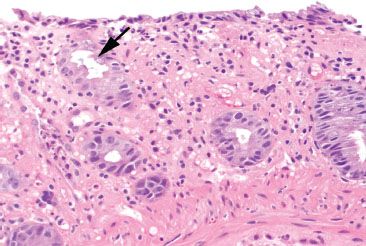

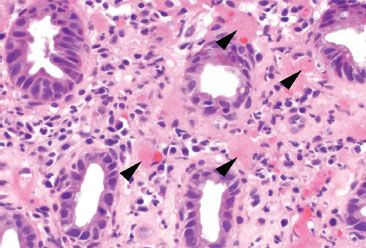

Figure 4.46 Acute colitis pattern, Campylobacter infection. Abundant crypt abscesses (arrowheads) indicate the presence of an acute colitis. Note the evenly spaced “bed of flowers” appearance of the colonic crypts (cut in cross section); there is no evidence of chronicity in this image from the right colon.

Figure 4.47 Acute colitis pattern, Campylobacter infection. Neutrophils (arrow) have crossed the crypt basement membrane and are present between the colonic epithelial cells.

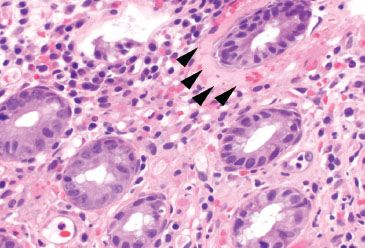

Figure 4.48 Acute colitis pattern, Campylobacter infection. Higher magnification of cryptitis shows neutrophils (arrowheads) within the colonic crypt epithelium.

Figure 4.49 Acute colitis pattern, crypt abscess in Campylobacter infection. A large collection of neutrophils is present within this crypt lumen (crypt abscess). Note the neutrophil crossing through the crypt epithelium (cryptitis) (arrowhead).

ISCHEMIC COLITIS PATTERN

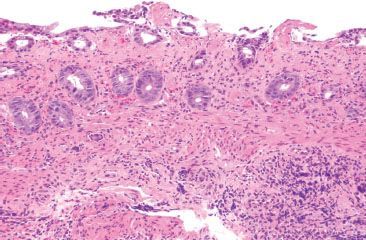

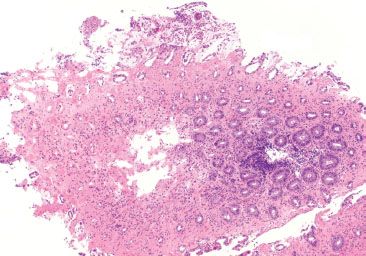

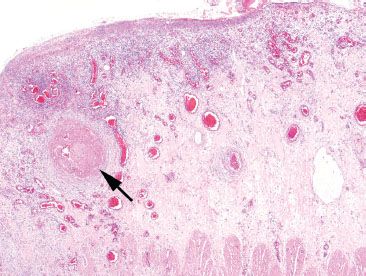

Figure 4.50 Ischemic colitis pattern. This example shows small and withered crypts near the surface. The surface epithelium has sloughed off in some areas, and lamina propria hemorrhage and hyalinization are present.

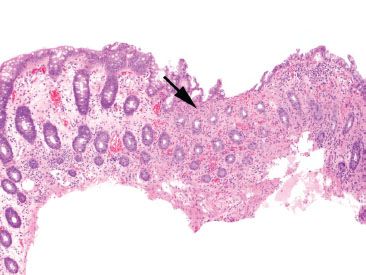

Figure 4.51 Ischemic colitis pattern. The striking finding at low magnification is the presence of “microcrypts” (arrow). Note the collapse of the hyalinized lamina propria in this area, causing a condensation of these crypts. Look at the left portion of this image for contrast to relatively normal crypts and lamina propria.

Mucosal ischemia causes a highly characteristic pattern of injury, including features of surface injury, loss of mucin, lamina propria hemorrhage and hyalinization, withered crypts, atrophic microcrypts, and lamina propria collapse (Fig. 4.50). The architectural pattern of withered crypts and microcrypts is distinctive at low magnification, and one might even refer to this pattern of injury as the “microcrypt pattern” (Fig. 4.51). Although ischemic injury is top among the differential diagnoses, other considerations include vascular injury (such as that seen in radiation colitis, amyloidosis, or vasculitis), infection (particularly Escherichia coli 0157:H7 and Clostridium difficile), and medications (NSAIDs, Kayexalate, and sevelamer).

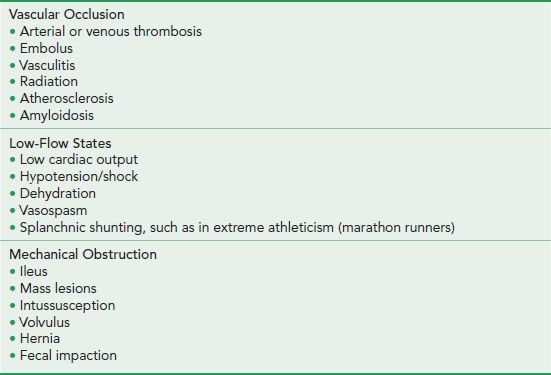

CHECKLIST: Etiologic Considerations for the Ischemic Colitis Pattern

Ischemia

Ischemia

Infection (E. coli, C difficile)

Infection (E. coli, C difficile)

Medication (NSAIDs, Kayexalate, sevelamer, ipilimumab, others)

Medication (NSAIDs, Kayexalate, sevelamer, ipilimumab, others)

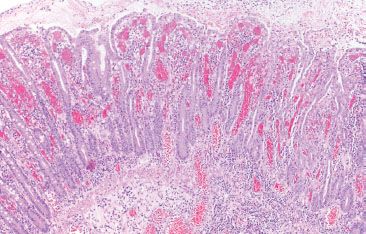

ISCHEMIA

Decreased blood flow and lack of oxygen to the GI tract result in necrosis or tissue damage, causing ischemia. There are several weak points in the colonic blood supply, known as watershed areas, which result from incomplete anastomosis of the marginal arteries and lack of sufficient collateral circulation. These watershed areas are more vulnerable to ischemic injury than other parts of the colon and include the splenic flexure (or Griffith’s point), the rectosigmoid region at Sudeck’s point, and the ileocecal region. Among the older population, ischemic disease is typically attributable to atherosclerotic mesenteric vascular disease, but the causes of colonic ischemia are many (Table 4.2). The histologic findings are dependent on the timing of the ischemic event (Figs. 4.52–4.63). Early and minimal injury, for example, occurs first as degeneration and sloughing of superficial epithelial cells, edema, and vascular congestion. Later, the epithelial cells become markedly attenuated and the crypts appear compressed and atrophic (“microcrypts”) as the lamina propria swells and hemorrhages. Within 5 hours of total acute vascular occlusion, almost the entire intestinal wall appears necrotic. These changes are devoid of acute inflammation until reperfusion occurs. Paradoxically, reperfusion further injures the tissues by introducing oxygen free radical formation,16 the severity of which is dependent on the duration of the preceding hypoxia.

TABLE 4.2: Causes of Colonic Ischemia

Figure 4.52 Ischemic colitis pattern, early. Early ischemic changes may show only lamina propria hemorrhage and edema with early sloughing of the superficial epithelium.

Figure 4.53 Ischemic colitis pattern, early. Lamina propria hemorrhage (arrowheads) is present.

Figure 4.54 Ischemic colitis pattern, withered crypts. Crypt epithelium becomes damaged and sloughs, giving a “withered” appearance to the crypts (arrowheads). Compare these withered crypts to the right side of the photo, which are better preserved.

Figure 4.55 Ischemic colitis pattern. This low magnification image emphasizes the microcrypt pattern. Small, withered crypts are present (arrow) along with lamina propria hyalinization. Note the homogenous pink appearance of the lamina propria in the area of the arrow. By comparison, the lamina propria at the base of the field is still preserved.

Figure 4.56 Ischemic colitis pattern. Note the microcrypt pattern of injury at scanning magnification. There is a gradient of crypt withering and dissolution that worsens as the surface epithelium is approached. Also, note the relatively homogeneous pink appearance of the hyalinized lamina propria.

Figure 4.57 Ischemic colitis pattern, microcrypts. Microcrypts with residual withered epithelium can be seen at the left (arrows), while crypts that have completely lost their epithelium are seen on the right (arrowheads). Again, note the quality of the lamina propria, which appears densely pink, rather than the typical colorless (or white) appearance.

Figure 4.58 Ischemic colitis pattern, early withering crypts. The surface epithelium in this example shows early sloughing. The crypt epithelium shows loss of cytoplasmic mucin.

Figure 4.59 Ischemic colitis pattern, early withering crypts. The surface epithelium shows attenuated epithelial cells with loss of cytoplasmic mucin. The crypt epithelium shows an early “withered’ appearance with undulation of the crypt luminal surface (arrow).

Figure 4.60 Ischemic colitis pattern, early lamina propria hyalinization. This early ischemic injury shows background lamina propria hemorrhage and minimal crypt damage; however, note the presence of lamina propria hyalinization surrounding the top right crypt (arrowheads). This homogenous pink material eventually replaces the lamina propria.

Figure 4.61 Ischemic colitis pattern, early lamina propria hyalinization. Similar to the previous example, these crypts show only early signs of cytoplasmic mucin loss; however, note the focal hyaline deposits (arrowheads) in the lamina propria.

Figure 4.62 Ischemic colitis pattern, early reperfusion injury. Notable in the Figures 4.52–4.61 is the near-complete absence of acute inflammation. Neutrophils are drawn to the site of injury only after reperfusion occurs, and therefore are not seen in early or acute ischemia. This example shows early reperfusion injury with an early neutrophilic infiltrate (arrowhead).

Figure 4.63 Ischemic colitis pattern, early reperfusion injury. Higher magnification of the previous figure shows crypt destruction due to a neutrophilic infiltrate.

KEY FEATURES of Ischemia:

• Ischemia can be caused by vascular occlusion, low flow states, or mechanical obstruction.

• The most common cause of ischemia among the elderly is atherosclerosis of the mesenteric arteries.

• Watershed areas prone to ischemia due to lack of sufficient collateral circulation:

• The splenic flexure (or Griffith’s point)

• The rectosigmoid region (Sudeck’s point)

• The ileocecal region

• Early histologic findings include sloughing of superficial epithelial cells, edema, and vascular congestion.

• Later stages include lamina propria hemorrhage, hyalinization, and microcrypt formation, followed by coagulative necrosis

• Acute inflammation is absent unless reperfusion occurs.

• Underlying vasculitis and radiation injury can cause ischemic mucosal changes (Figs. 4.64–4.66).

• Beware not to overcall crush artifact from biopsy forceps as ischemic change.

• Pseudomembranes may be seen.

Figure 4.64 Ischemic colitis pattern, radiation injury. Withered microcrypts (arrowheads) can be seen in radiation injury. This patient had radiation proctitis secondary to radiation treatment for bladder cancer.

Figure 4.65 Ischemic colitis pattern, radiation injury. Higher magnification of the previous image reveals the presence of abundant apoptoses (arrowheads), a red flag to radiation-induced injury.

Figure 4.66 Cellular atypia of radiation injury. Large, atypical cells (arrow) are seen following radiation injury. Their presence can raise concern for recurrent malignancy, but note the abundant cytoplasm, which conserves the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N:C) ratio. Another clue is the prominent vesicular appearance of these atypical cells.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

Crush Artifact from Biopsy Forceps Can Mimic Ischemic Injury

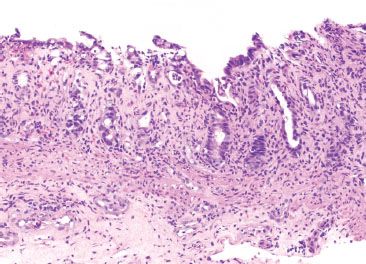

Cautery effect and crush injury due to biopsy forceps (“squeeze artifact”) may strip epithelial cells from the surface and crush glands that can be mistaken for atrophic microcrypts (Fig. 4.67–4.68). To contrast, true ischemic injury will show lamina propria hemorrhage and degenerative cellular changes, such as loss of the apical brush border and ghostlike nuclei. There is no tissue response to biopsy forceps squeeze artifact.

Figure 4.67 Crush (“squeeze”) artifact mimicking ischemic colitis pattern. Crush artifact from biopsy forceps can dislodge crypt epithelium, leaving behind an empty space that mimics the microcrypts of ischemia. Avoid this pitfall by noting the absence of other ischemic features, such as lamina propria hemorrhage, loss of cytoplasmic mucin, and lamina propria hyalinization.

Figure 4.68 Cautery artifact mimicking ischemic colitis pattern. Cautery causes thermal injury and distorts the colonic crypts. In this example, one might consider the possibility of ischemic injury, due to the loss of surface epithelium and presence of smaller crypts (arrows). Note, however, the absence of lamina propria hemorrhage or hyalinization.

PEARLS & PITFALLS

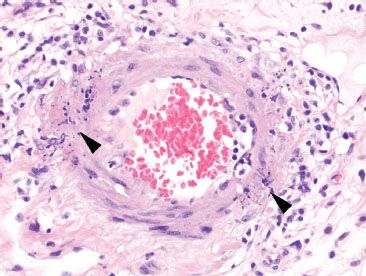

Evaluation for Underlying Vasculitis Can be Tricky in Biopsy Material

Which came first, the chicken or the egg? Although underlying vasculitis can certainly cause mucosal ischemia, vascular thrombi and inflammatory changes can be secondary to ischemic-reperfusion injury. As a result, primary vascular injury should be evaluated in areas not directly subjacent to ischemia or ulceration, and close clinical, radiologic, and serologic correlation should be performed in cases suspected of primary vasculitis (Fig. 4.69–4.72).

Figure 4.69 Ischemic colitis pattern, venulitis in Behçet disease. One should always consider vasculitis as a cause of ischemia or ulceration, but take care to look in areas away from ulcers. This example shows a striking lymphocytic venulitis (arrow) that has obliterated the small vein. It is easier to search for small muscular arteries (pictured top right) and then look in the proximity for the paired vein.

Figure 4.70 Ischemic colitis pattern, venulitis in Behçet disease. Note how the markedly damaged and inflamed vein (arrow) blends into the background. By contrast, the pristine and unaffected artery is easily identified.

Figure 4.71 Ischemic colitis pattern, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). This segment of colon was resected for ischemia. Note the extensive surface ulceration. An underlying vessel shows a large fibrin thrombus (arrow). However, due to the proximity to the ulcer, it is unclear whether the vascular change is causative or the result of the ulcer. One must search for vascular changes away from the ulcer bed.

Figure 4.72 Ischemic colitis pattern, leukocytoclastic vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Sure enough, further examination in the previous case revealed karyorrhectic debris (arrowheads) of small vessel necrotizing vasculitis, consistent with the patient’s history of SLE.

INFECTION (Escherichia coli 0157:H7 and Clostridium difficile)

Certain infectious agents also produce an ischemic pattern of injury, namely enterohemorrhagic E. coli (E. coli 0157:H7) and C. difficile (Fig. 4.73–4.75). The histologic distinction between ischemia and infection can be nearly impossible, but observers cite the presence of lamina propria hyalinization as a feature of ischemia that is absent in infectious colitis (Fig. 4.76).17 Another clue is the distribution of disease, as infection diffusely involves the colon, whereas ischemia preferentially involves the watershed areas. Undoubtedly, stool studies remain the gold standard for diagnosis.

KEY FEATURES of Infection:

• Infection by E. coli 0157:H7 or C. difficile can be histologically identical to ischemia.

• Hyalinized lamina propria and withered crypts are not typical of C. difficile colitis.

• C. difficile colitis is more diffusely distributed in the colon compared to ischemic colitis.

• Fibrin thrombi are seen in association with E. coli 0157:H7 infection, but are not specific.

• Pseudomembranes are a feature of infectious colitis, but can also be seen in ischemic colitis.

Figure 4.73 Ischemic colitis pattern, Escherichia coli infection. Infection can cause ischemic-like features. This example of E. coli infection shows withered and atrophic crypts with partial surface denudation and loss of cytoplasmic mucin. The findings are nearly indistinguishable from those of true ischemic injury.

Figure 4.74 Ischemic colitis pattern, enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection. A clue to enterohemorrhagic E. coli infection (strain O157:H7) is the presence of fibrin thrombi (arrowheads) within small capillary vessels. Focal residual crypt bases remain (arrows).

Figure 4.75 Ischemic colitis pattern, Clostridium difficile infection. The archetypal feature of C. difficile colitis is the presence of pseudomembranes; however, early C. difficile colitis shows ischemic pattern features, such as the microcrypt pattern seen here. An early pseudomembrane is pictured, but these are not always present.

Figure 4.76 Ischemic colitis pattern, lamina propria hyaline. Although significant histologic overlap exists between infectious and ischemic etiologies, the presence of lamina propria hyalinization is cited as a distinctive feature of ischemia. A homogenous pink hyaline material replaces the lamina propria and its cellular constituents.

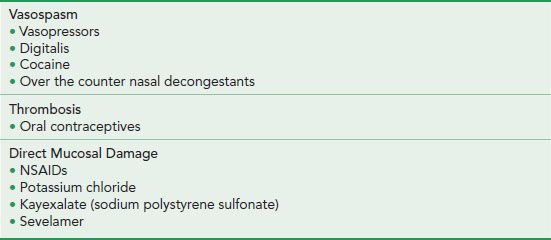

TABLE 4.3: Mechanism of Medications Causing Ischemic Colitis

MEDICATION INJURY

A number of medications cause ischemic injury by a variety of mechanisms (Table 4.3). Also known as polystyrene sulfonate, Kayexalate is a cation exchange resin used to treat hyperkalemia and is commonly found among the medication regimens of renal failure patients. The resin can be found anywhere along the GI tract, as it is administered via nasogastric tube, orally, or via rectal enema. Kayexalate was introduced in 1958 with the notable absence of any randomized clinical trial regarding its efficacy and safety. In the early use of Kayexalate, complications included bowel concretions and medication bezoars within the bowel. As a result, the original water-based suspension was replaced by a sorbitol suspension that caused an intentional osmotic diarrhea, thereby reducing bowel impactions. However, not long after, reports of colonic necrosis and resulting death surfaced, with evidence that sorbitol was the responsible agent.18 In a more recent systematic review of 58 cases, Kayexalate (with and without sorbitol) was linked to ischemic colitis, colonic necrosis, perforation and bleeding, with a notable mortality rate of 33% among patients manifesting GI injury.19 See also Resins, Pigments, Esophagus Chapter.

Key Characteristic Morphologic Features of Kayexalate:

• Purple on H&E.

• Hot pink on PAS/AB.

• Narrow, rectangular “fish-scales” or a “mosaic” appearance due to cracking lines at regular intervals. These “fish-scales” are seen in both small and large crystal fragments (Figs. 4.77 and 4.78).

• Can be differentiated from sevelamer crystals (a phosphate lowering agent with possible injurious potential), which show broad, curved, irregularly spaced “fish-scales” with a variably eosinophilic to rusty brown color on H&E stain, and a violet color on PAS/D.20

Figure 4.77 Ischemic colitis pattern, Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate). This segment of colon was almost entirely necrotic. Embedded in the luminal debris were numerous purple resin crystals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree