| 12 | Colitis—Inflammatory Bowel Diseases b and Other Forms of Colitis |

The following abbreviations are used in this chapter:

CD | = | Crohn disease |

DALM | = | dysplasia-associated lesion or mass |

DD | = | differential diagnosis |

DGVS | = | German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaftfür Verdauungs-und Stoffwechselkrankheiten) |

HGIN | = | high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

IBD | = | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

LGIN | = | low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

NSAID | = | nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

PSC | = | primary sclerosing cholangitis |

UC | = | ulcerative colitis |

Definition

Definition

Colitis. The intestinal mucosa has a limited number of possible reactions to microbial, chemical, or immunological irritants: edema, erythema, erosion, ulcer, necrosis, stricture, and scarring. Various diseases differ in terms of typical characteristics, intensity, and particularly distribution of these reactions, enabling differential diagnosis. Isolated changes are, on the contrary, unspecific. NB: Previous systemic or topical treatments can influence or mask characteristic changes.

Clinical Significance of Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Clinical Significance of Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease occur all over the world, but they appear more frequently in western industrialized countries. In North America, an estimated 1.3 million people are affected; in Europe, 1.9 million; and in Germany, 300000. Pathophysiologically, chronic IBD manifests as a deregulated immune response of the intestinal mucosa to microbes or other environmental irritants in individuals who are genetically predisposed to increased susceptibility. In Europe there is a typical north-south gradient in incidence and prevalence. The rate of Crohn disease in Germany is near the European average, at 5.2 patients per 100000. The first manifestation usually occurs in earlier decades, though there is a second peak later in life (especially for ulcerative colitis; less so for Crohn disease). The two diseases can be clearly distinguished in terms of immunopathogenesis and clinical appearance. Only 1% of 5-10% of attacks remains unclear and is classified as indeterminate colitis. Sero-logical markers (antibodies such as ANCA and ASCA) can be useful for differential diagnosis.

Clinical manifestation. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease have a number of symptoms in common: diarrhea, abdominal pain and peranal bleeding. Ulcerative colitis usually occurs in episodes with intermittent periods of remission. Crohn disease may also occur in episodes, but there is an active, chronic form as well. In addition, Crohn disease can be divided into the perforating, fistulizing type, the active, chronic inflammatory type, and the fibrostenotic type. Progression and prognosis may eventually be predictable using genetic markers, but this is not yet possible.

Treatment. Anti-inflammatory drugs can be used to effectively treat the mucosal surface. Corticosteroids and immunosuppressants are the first-line therapy for severe cases. An anti-TNF antibody is sometimes used to treat Crohn disease. Nonetheless, more than 70% of individuals with Crohn disease have to be operated on during their lifetime and many have signs of recurrence of the disease afterward. Drug therapy usually corresponds to increasing level of severity (step-up approach). A more recent approach involves beginning therapy with a combination of stronger drugs and then reducing their use (top-down approach), but this approach requires further evaluation. Remission-maintaining drugs are indicated for chronic active CD, steroid-refractory CD, and usually the perforating type. However, determining which drugs maintain remission is difficult, not least because endoscopically visible signs of activity do not correlate well with disease activity and progression (5). Ulcerative colitis refractory to treatment is frequently treated with surgical intervention, i. e., usually proctocolectomy. Proctocolectomy is often followed by inflammation in the ileal reservoir, so-called pouchitis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of chronic IBD is based on patient medical history and clinical findings. Endoscopy, i.e., ileocolonoscopy with biopsies, is essential and is the main diagnostic procedure. Radiography, ultrasound, and increasingly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as bacteriological and serological investigation, are also used.

Endoscopy. Colonoscopy is essential for diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and, in isolated cases, assessing disease activity. Differential diagnosis is primarily based on macroscopic findings. Though histological evaluation can also be useful for classification, the pathologist cannot function as a “referee” who makes the final decision in the case of inconclusive endoscopic findings. Endoscopy plays less of a role in monitoring treatment and determining prognosis. In isolated cases, endoscopy can be used therapeutically (CD) and it also plays an important role in carcinoma prevention.

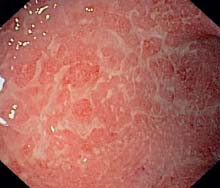

Fig. 12.1 Ulcerative proctitis. Sharp demarcation between inflamed mucosa (left) and normal mucosa in upper rectum.

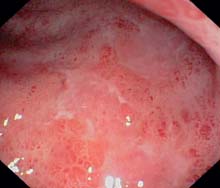

Fig. 12.2 Ulcerative proctitis. Florid attack in rectum with abrupt transition to normal sigmoid colon above.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Indications for Ileocolonoscopy:

clarification of longstanding diarrhea (> 4 weeks),

clarification of longstanding diarrhea (> 4 weeks),

differentiation of inflammatory changes,

differentiation of inflammatory changes,

surveillance for confirming chronic course and thus diagnosis,

surveillance for confirming chronic course and thus diagnosis,

evaluation of disease activity (more for UC than CD),

evaluation of disease activity (more for UC than CD),

determine extent of inflammation related to grave changes in disease course,

determine extent of inflammation related to grave changes in disease course,

preoperative staging, i.e., evaluation of current attack prior to planned resection,

preoperative staging, i.e., evaluation of current attack prior to planned resection,

routine surveillance of longstanding UC for diagnosing dysplasias (intraepithelial neoplasias) for carcinoma prevention (less clear for CD),

routine surveillance of longstanding UC for diagnosing dysplasias (intraepithelial neoplasias) for carcinoma prevention (less clear for CD),

clarification of recently appearing symptoms (partial obstruction, bleeding),

clarification of recently appearing symptoms (partial obstruction, bleeding),

therapy: stricture dilation (CD),

therapy: stricture dilation (CD),

future prospects: diagnosis by means of tissue biopsy for microbiological detection using gene chips

future prospects: diagnosis by means of tissue biopsy for microbiological detection using gene chips

Ulcerative Colitis

In most cases, ulcerative colitis presents with characteristic endoscopic appearances. Progression corresponds to the length and severity of episodes. Disease course is seldom of a chronic, smoldering nature.

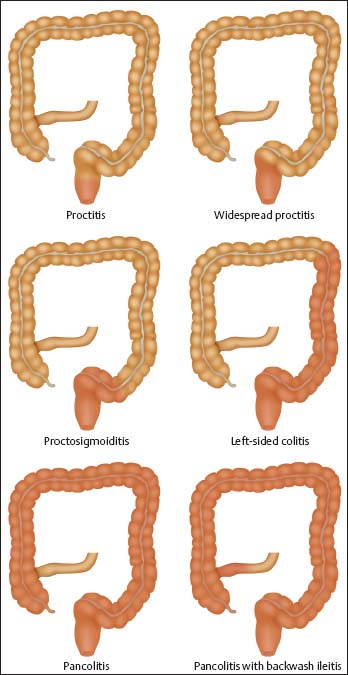

Spread of inflammation. Active UC inflammation of the mucosa is continuous and symmetrical. It can affect the entire colon or only part of it and can occur as proctitis or proctosigmoiditis, spreading into the upper sigmoid colon; left-sided colitis can spread to the splenic flexure or become pancolitis. The rectal mucosa is typically involved. Total colonoscopy can provide exact information about the extent of inflammation. The border between affected and healthy mucosa is usually clearly demarcated (Figs. 12.1, 12.2). However, discontinuous manifestations of UC have also been cited, e.g., in the form of “proctitis” with “cecitis,” so that atypical manifestations must also be considered (1, 2).  12.4b from our own clinical files shows an example of UC involving the cecum, with remission of the right side and a florid attack involving the left side. Fig. 12.3 gives an overview of the extent of colonic involvement in ulcerative colitis.

12.4b from our own clinical files shows an example of UC involving the cecum, with remission of the right side and a florid attack involving the left side. Fig. 12.3 gives an overview of the extent of colonic involvement in ulcerative colitis.

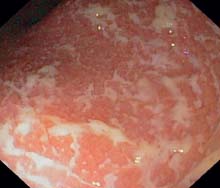

12.1 Ulcerative colitis: fibrinous exudates, edematous and granulated mucosa in an acute episode

12.1 Ulcerative colitis: fibrinous exudates, edematous and granulated mucosa in an acute episode

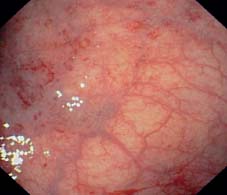

a Recent fibrinous exudates, appearing as a whitish covering on an already edematous mucosa (sigmoid colon).

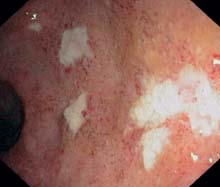

b Fibrinous material on an edematous and granulated mucosa (rectum).

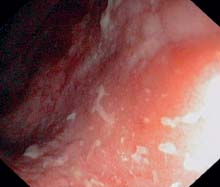

c Masses of fibrin and blood (sigmoid colon).

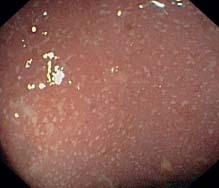

d Ulcerative proctitis: fibrinous exudates.

e Pancolitis, chronic ulcerations, also recent attack with fibrinous material in the ascending colon.

f Florid inflammation in the sigmoid colon with typical fresh fibrinous coverings, already weblike, precursor of ulceration.

g Recent attack of pancolitis, fibrinous exudates in the cecum. The ileocecal valve and small intestinal mucosa are not involved and are not inflamed.

h Ulcerative proctitis: tiny dot-shaped fibrinous exudates (rectum).

i Florid proctitis, Löfberg (grade 2) with confluent weblike fibrinous coatings, also increased vulnerability.

Fig. 12.3 Varying extent of colonic involvement in ulcerative colitis.

Fig. 12.4 Minimal inflammation, already abating, traces of hemosiderin resulting from petechial bleeding (sigmoid colon).

Fig. 12.5 Nearly circular mucosal necrosis in chronic UC, with only pseudopolypoid, regenerated mucosa remaining (sigmoid colon).

Fig. 12.6 Florid sigmoiditis in UC. Inflammation spreading to proximal colon in recent onset of recurrent attack, delayed onset in specific areas (right side of image) vessel pattern is remaining, only slightly altered by prior attack.

12.2 Ulcerations in ulcerative colitis

12.2 Ulcerations in ulcerative colitis

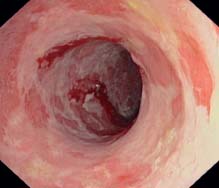

a Weblike confluent ulcerations in an acute episode (rectum).

b Recent attack: flat, recent ulcer, fibrin in the background (sigmoid colon).

c Flat ulceration and mucosal petechiae in a treated attack (sigmoid colon).

d Confluent ulcers and fibrinous masses in an acute attack (lower sigmoid colon).

e Significant, almost circular mucosal necroses and flat ulcerations related to active chronic UC with persistent attack.

f Deep ulcerations can appear with a high degree of activity; vulnerability is overall greatly increased. Distinguishing UC from other forms of colitis is more difficult here; main criteria for UC are continuous inflammatory process and mucosal erythema.

12.3 Löfberg Classification of UC

12.3 Löfberg Classification of UC

Löfberg score, grade 1 diffuse granularity, edema, fragmented light reflection, loss of normal vascular pattern.

Löfberg score, grade 2 all criteria of grade 1 + hyperemia, vulnerability, fibrinous exudates.

Löfberg score, grade 3 all criteria of grades 1 and 2 + ulcerations.

Fig. 12.7 Pronounced development of pseudopolyps with signs of florid inflammation on their surfaces; causing moderate stenosis.

Fig. 12.8 Pale tiny pseudopolyp, smooth surface, thus appearing like remaining local mucosa or partially regenerated mucosa.

Fig. 12.9 Pseudopolyps with typical whitish surface, similar to a sugar glaze, which usually does not cover the polyp completely.

12.4 Clinical course of ulcerative colitis: chronic form

12.4 Clinical course of ulcerative colitis: chronic form

a Pancolitis, longer duration, atrophied mucosa, and loss of haustra in ascending colon.

b Longstanding ulcerative pancolitis, view into the ascending colon and cecum with apparently atrophied mucosa of the ascending colon, but florid changes in cecum (cecitis).

c-e Inactive stage. c Atrophied mucosa, whitish with solitary, regenerated vessel. Destroyed vessel pattern is always a sign of prior attack and after several episodes it will never return to its normal condition. d Another inactive area. The mucosa is flat and hardly rises during biopsy. A few elevated mucosal segments in between, so-called pseudopolyps. e Even in inactive intestinal segments, patchy inflammation focals can appear; in this case it is a circumscribed area which shows all typical characteristics of a recently inflamed area.

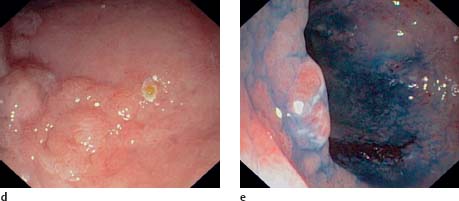

12.5 DALM (Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass) in ulcerative colitis

12.5 DALM (Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass) in ulcerative colitis

a-c DALM resection at the hepatic flexure. a Flat polypoid lesion in the hepatic flexure, atypical appearance for an adenoma: DALM, histologically LGIN.b After indigo carmine staining and injection: DALM at the hepatic flexure. c Previous endoscopic resection of the DALM lesion (histologically: no further intraepithelial neoplasias in the surrounding area).

d, e DALM in the sigmoid colon. d Raised polypoid structure in the sigmoid colon (DALM). The patient also had backwash ileitis and PSC. e The somewhat displaced lesion can be better visualized against the surrounding granulated mucosa with chromoendoscopy (indigo carmine). Histologically HGIN, partly carcinoma in situ. Afterward, the patient underwent proctocolectomy, which did not reveal an invasive carcinoma.

f DALM in rectum, tinged with blood.

However, polypectomy can only be the definitive therapy for DALM when the presence of dysplasia (intraepithelial neoplasias) in the flat mucosa has been investigated and ruled out using multiple biopsies. This sometimes requires a very large number of excisional biopsies. It takes 33 excisional biopsies to find dysplasia with 90% certainty and 56 excisional biopsies per examination for 95% certainty (4). Recent studies have shown that targeted biopsies following methylene blue staining could increase the rate of detection of dysplastic epithelium in flat mucosa (3) ( 12.5 e).

12.5 e).

Fig. 12.10 Pancolitis in UC. The appendix is also involved and the appendiceal opening shows typical ulceration.

Fig. 12.11 Chronic pancolitis in UC. Ileoce-cal valve involvement and backwash ileitis. The same patient also has PSC.

Fig. 12.12 Pancolitis in UC. Ileocecal valve involved in pronounced backwash ileitis and showing polypoid changes.

Fig. 12.13 Pronounced backwash ileitis. Edema, granularity, and formation of a small aphthous ulcer in the terminal ileum.

Fig. 12.14 Ileoanal pouch inflammation (pouchitis). Acute inflammatory changes similar to UC with somewhat patchy fibrinous plaques and significant erythema.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basic colonoscopic inflammatory appearances: swelling, erythema, mucoid or pus secretion, and mild to severe epithelial destruction, ranging from an erosive defect to deep ulceration.

Basic colonoscopic inflammatory appearances: swelling, erythema, mucoid or pus secretion, and mild to severe epithelial destruction, ranging from an erosive defect to deep ulceration.

12.2f),

12.2f),

12.1a, b),

12.1a, b),

12.2a).

12.2a). Early signs or signs of recurrence of inflammation include masses of mucous appearing on the mucosal surface as a creamy, whitish coating (

Early signs or signs of recurrence of inflammation include masses of mucous appearing on the mucosal surface as a creamy, whitish coating ( 12.1 e). With low-grade inflammation, vascular pattern can be distorted, weakened, or lost (due to edema and inflammation). This is partly caused by loss of transparency of the mucosa. Erythema is usually diffuse and is evidence of an active phase, especially when accompanied by granularity and fragmentation of reflected light (

12.1 e). With low-grade inflammation, vascular pattern can be distorted, weakened, or lost (due to edema and inflammation). This is partly caused by loss of transparency of the mucosa. Erythema is usually diffuse and is evidence of an active phase, especially when accompanied by granularity and fragmentation of reflected light ( 12.1a, b).

12.1a, b).  12.2a). Regardless of the various shapes—linear, serpiginous (“snakelike”), circular, or oval—all of these ulcers share the common characteristic of typically being surrounded by a reddened and vulnerable mucosa (

12.2a). Regardless of the various shapes—linear, serpiginous (“snakelike”), circular, or oval—all of these ulcers share the common characteristic of typically being surrounded by a reddened and vulnerable mucosa ( 12.2). Petechiae are another sign of disease activity (

12.2). Petechiae are another sign of disease activity ( 12.3).

12.3). 12.4a) (analogous to a “stiff tube” in radiological imaging).

12.4a) (analogous to a “stiff tube” in radiological imaging).  12.5). Adenomalike polyps, and sometimes even DALM, can be removed by polypectomy, which can also be the definitive treatment (

12.5). Adenomalike polyps, and sometimes even DALM, can be removed by polypectomy, which can also be the definitive treatment ( 12.5 c).

12.5 c).