Fig. 6.1

Goodsall’s rule states that anal fistula with anterior secondary openings tend to follow a straight radial trajectory to a primary opening in the anal canal at the level of the dentate line. Posterior secondaries follow a curvilinear trajectory into a posterior midline primary. Anterior secondary openings found greater than 3 cm from the anus also tend to follow a curvilinear path into the posterior midline crypt

Park’s classification of fistulas represents the de facto description of fistulas today [5]. His initial classification scheme was slightly more elaborate, but included the following four basic fistula types (with percentages based on his preliminary series of 400 patients): intersphincteric (45 %), transphincteric (29 %), suprasphincteric (20 %) and extrasphincteric (5 %). Today, these percentages have changed slightly based on larger series to represent the scope of clinical disease as follows: intersphincteric (70 %), transphincteric (20–25 %), suprasphincteric (1–3 %), and extrasphincteric (1–2 %) (Fig. 6.2) [6].

Fig. 6.2

Park’s classification of anal fistulas: (a) low intersphincteric; (b) low transphincteric; (c) supralevator; (d) two variations of extrasphincteric fistula. On the left is a variant seen in iatrogenic recurrent fistulas or associated with Crohn’s disease. On the right is an uncommon variant of cryptglandular origin

Intersphincteric fistulas are the most common. They traverse a minimal distance and extend from an internal opening near the intersphincteric groove to an external location typically located outside the anal margin. The intersphincteric groove represents the palpable step off between the internal sphincter and the subcutaneous portion of the external sphincter. Within a few millimeters, it represents a surrogate landmark for the dentate line where the anal crypts reside. Intersphincteric fistula is a result of a drained perianal abscess originating from a gland that did not extend beyond the external sphincter. The fact that this is the most common type of fistula is consistent with the anatomic description that 80 % of glands are submucosal, 8 % extend to the internal sphincter, 8 % course to the longitudinal external muscle, and only 3 % penetrate the internal sphincter extending beyond the intersphincteric space [7].

Transphincteric fistulas are the next commonest. These involve both the internal and external sphincters and pass into the ischioanal fossa. These typically result from a peri-rectal abscess. The length of the fistula is determined by the location of the previous incision and drainage or site of spontaneous decompression.

Suprasphincteric fistulas are relatively rare. These curvilinear fistula tracts originate at the level of the dentate line but traverse cephalad above the puborectalis before turning downward through the ischioanal fossa to reach the perianal skin.

Extrasphincteric fistulas are usually caused by overzealous probing and creation of false fistula tracts. These result in an internal opening above the sphincter complex that passes through the levators rendering them amongst the most difficult types to treat.

The concept “complex fistula” is a common term in the surgical vernacular, albeit not a part of Park’s classification. A useful definition of “complex fistula” is any fistula other than a simple intersphincteric or low transphincteric configuration. The term further may be used to describe those that include multiple tracks, anterior location in females, recurrent fistulas, those with preexisting incontinence, previous radiation, or in the setting of another disease process (such as Crohn’s disease) [8]. It is termed complex because the treatment requires a more complicated approach and cannot be treated by simple fistulotomy. The “complex fistula” has been a catalyst of much innovation, although no single approach has proven superior at adequately eradicating this disease process. Infections tracking above the levator muscles may ultimately form suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric fistula. The former course between the sphincter muscles; the latter course lateral to the external sphincter muscle. Abdominal pelvic infections may disseminate into the retrorectal and supralevator spaces as well as the ischioanal fossae via Alcock’s canals acutely. Drainage lateral to sphincter complex is recommended but may result in an extrasphincteric fistula.

One additional type of fistula includes the horseshoe fistula. These originate most commonly from either bilateral intersphincteric or transphincteric fistula tracts arising from a single posterior midline crypt. They are important to recognize, because they are often mismanaged due to a failure to identify the underlying source—infection in one of the post-anal or posterior space(s): superficial, deep, supralevator, and rarely retrorectal.

Clinical Evaluation

Anal fistula arising in the setting of specific diseases should be investigated according to the clinical context in which they present. The classic example is chronic inflammatory bowel disease—particularly Crohn’s. Evaluation includes the documentation of the state of the rectal mucosa assessed by endoscopic examination prior to any attempt at fistulotomy. Satisfactory results are much lower with the success rates of definitive surgery often below 50 % when active proctitis is present [9]. Moreover, sphincter function should be assessed and clearly documented. If appropriate, an incontinence score should be assigned to these patients. All procedures for the surgical correction of anal fistula have the potential of altering fecal continence. However, preexisting alterations in continence are important to document preoperatively. Finally, investigation into any imunocompromised state, such as HIV, should be a part of the history. There is conflicting evidence whether low CD4+ counts affect wound healing. Patients on Highly Active Antiviral Therapy (HAART) with normal CD4+ counts should be treated no differently than non-immunosuppressed patients [10–12].

In the absence of any complicating factors, most colorectal surgeons will proceed with an exam under anesthesia (EUA) and definitive surgical eradication of the fistula by a variety of surgical techniques currently available. The role of preoperative imaging has been debated. It remains unclear that this adds any additional information to the skilled practitioner. Arguments for the preoperative use include that it aids in operative planning and counseling the patient as well as allowing the practitioner to proceed with an appropriate definitive procedure at the first operation [13, 14]. Opponents argue that even with complex fistula tracts, definitive management at the first procedure is not always possible. The primary goal should be control of anorectal sepsis, with definitive procedure reserved for a time when there is decreased infection and inflammation of surrounding tissues [15]. Although imaging can serve to correctly identify the course of the fistula tract in the majority of patients, it remains unclear whether the time and expense to perform these studies is justified, especially since most patients will have low-lying, simple fistulas. The true advantages of these imaging techniques come in delineating high, multiple, or recurrent tracts. It is the authors’ preference to always perform EUA and definitive fistula management at the time of the first surgery if possible. Adjunctive imaging techniques are reserved for those whose anatomy is unclear at the time of surgery. A review of 101 patients showed that primary crypt identification was possible 93 % of the time with surgery alone. Hydrogen peroxide was seen to drain through the internal opening of 83 % of those who underwent injection through the external opening of the fistula [16].

There are other useful techniques during EUA for anal fistula. Palpation of the intersphincteric groove with an index finger often reveals palpable induration or a divot in the area of the originating crypt. Superficial fistula tracts can also be palpable from their external opening into the anal canal. Some authors employ a crochet-type hooked probe to identify the internal opening. Others apply a clamp lateral to the external opening in order “to straighten” the tract. The safety and efficacy of these last two maneuvers is unknown.

The authors’ practice is ritualistic and regimented in the following fashion during the course of EUA for anal fistula:

1.

Topographical inspection of the perianal region

2.

Palpation of the intersphincteric groove and the tissues surrounding the external opening(s)

3.

Examination of the anal canal with a Parks retractor

4.

Injection of the external opening(s) with hydrogen peroxide ± dilute methylene blue; multiple external openings are injected from furthest away to those most medial to the anal verge

5.

Passage of a silver probe gently from the external opening to the internal opening.

Of note, multiple external openings are common. However, more than one internal opening is also known to occur. Therefore, passage of the probe as an initial maneuver may be misleading as well as potentially iatrogenic if a false opening is created. A case in point is evident in Fig. 6.3.

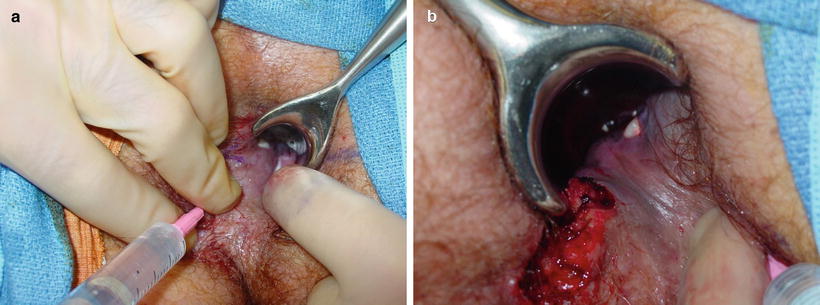

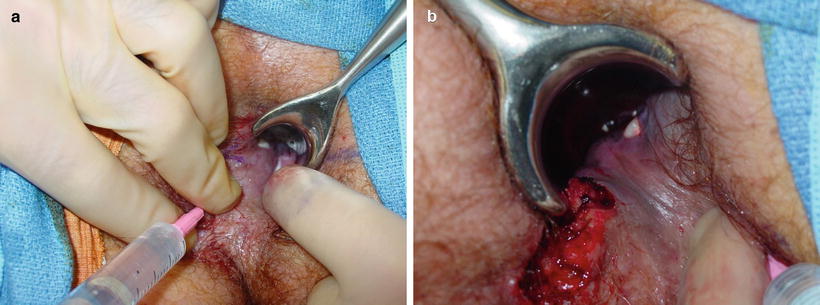

Fig. 6.3

(a) Injection of a left anterolateral external opening. Hydrogen peroxide emanates from two adjacent cypts via radial trajectories. (b) Injection of a right second anterolateral external opening a third independent radial tract in this same patient. This case underscores the importance of a stepwise, regimented approach for the evaluation of anal fistula at the timer of EUA

Failure to identify a primary internal opening is not uncommon. The most traditional approach in this setting is to sequentially follow the tract from the external opening hopefully to its origin at the internal opening. This approach has inherent risks especially when following a deep fistulous trajectory. It is eminently reasonable to back out and obtain either an ultrasound or MRI. Another potential promising alternative in this setting is the video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) technology platform. Further experience is necessary.

Radiologic Evaluation

In cases of complex fistulas or recurrent anal fistulas, the use of imaging techniques should be strongly considered. It should be noted that the most common reason for extrasphincteric fistula tract development is iatrogenic probing and creation of false fistula tracts. Therefore, if it is not possible to delineate or control the entire fistula tract at the time of the index operation, it is advisable to control what can be identified and investigate the anatomy further with advanced imaging. There exist numerous options for imaging of fistulas. These include CT, MRI, ultrasound, and fistulography.

Fistulography using fluoroscopy and computed tomography (CT) are regarded as obsolete because of the radiation burden, and suboptimal visualization of fistulas using contrast media [17]. An exception may be in the acute setting with suspected abscess. CT scanning is useful acutely to define the location of an infection where there is a paucity of clinical findings. This allows the practitioner to define any deeper areas of infection and suggest an origin (such as a supralevator, pure intersphincteric, extrasphincteric, or horseshoe abscesses). This additional information is useful to know before proceeding to the operating room to deal with an abscess with appropriate aggressiveness. CT imaging plays little or no role in the evaluation of chronic fistula tracts.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree