Fig. 4.1

Obstruction of anal gland at its crypt may result in infection disseminating via three pathways to form abscesses potentially in five anatomic locations (left). These abscesses may form fistulous trajectories, which mirror their initiating pathways and ending at their site of spontaneous versus surgical drainage (right)

Clinical Evaluation

The routes of dissemination and primary space of occupation speak directly to the signs and symptoms presented by patients. Anatomy truly begets semiology—a patient’s signs and symptoms. Perianal infections rarely pose a diagnostic problem. Patients present within a few days of onset of pain with obvious signs of an infection near the anal margin. Infections in this position are characterized by intense pain presumptively because these processes propagate from the sphincters through the micro-facial compartments formed by the corrugator cuti. A relatively small amount of suppuration can produce dramatic symptoms with obvious signs.

Abscesses in the ischioanal spaces behave quite differently. This compartment is comparatively large and comprised mostly by adipose tissue. Early abscesses may not demonstrate any overt physical signs. Many more days are generally required for detection by simple inspection. Before the evolution of obvious signs of rubor, dolor, calor, etc., ischioanal abscesses may be detected with a “bi-digital” rectal examination. With the examining index finger within the anorectum, the soft tissues are palpated by apposition of the thumb. Fullness of the ischioanal fossa is suggestive of an abscess in this position (Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.2

Ischioanal space abscesses may be detected by palpation of the ischioanal fossa with the tissues palpated between the examiner’s index finger and thumb (“bi-digital examination”)

Late presentation of ischioanal abscesses can be very dramatic especially in the setting of horseshoe abscesses, which occupy both fosse and one of the posterior spaces (Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3

A classic late presenting horseshoe abscess. Rubor and cellulitis are evident on both the left and right sides of the anal verge. The skin overlying the post-anal space is bulging with incipient epidermolysis

Intersphincteric abscesses may also pose a diagnostic challenge because of the relative paucity of physical signs. However, they represent a process, which is dissecting between the internal and external sphincters. Pain may in this scenario be amplified with bowel movements. Anorectal tenderness is the hallmark symptom. Many patients do not or will not tolerate an adequate examination. Imaging may be useful in this scenario (Fig. 4.4).

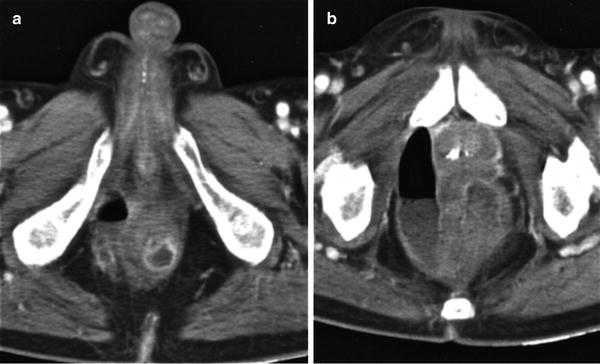

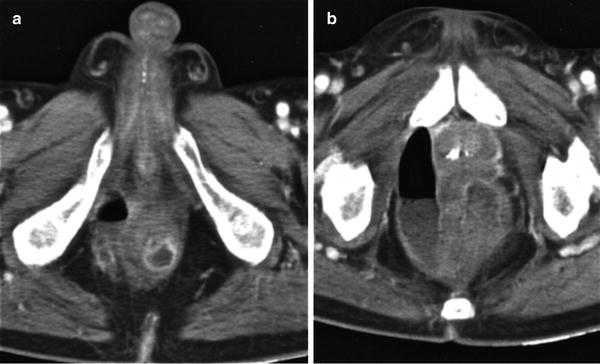

Fig. 4.4

A cystic fluid collection between the internal and external sphincter muscles of the mid-anal canal is evident on the CT scan. Note the incipient fat stranding in the bilateral ischioanal fossa. This is a classic appearance of a low-lying intersphincteric abscess

A patient’s symptoms may provide other subtle clues regarding the anatomic configuration of an anorectal infection. Patients with abscesses above the sphincters may refer tenesmus, lower abdominal or pelvic pain. A primary abscess above the levators is confirmed by palpation of a boggy mass within the rectum on digital rectal examination. Palpation of rectal fullness in the setting of a patient with pain, possible fever and leukocytosis implies infection above the levator ani complex. There are three potential possible explanations:

1.

A submucosal abscess

2.

An intersphincteric supralevator abscess

3.

An extrasphincteric supralevator abscess

Multiple space abscesses are not uncommon. The classic example is a horseshoe abscess arising from a posterior midline crypt. The propagation of infection arising from a posterior midline cryptoglandular complex may also propagate superficially, intersphincterically, or across the sphincters. Propagation of an infection across the sphincters into the ischioanal fossa is referred to as transphincteric. Those that cross the entire sphincter complex to reach the supralevator space are essentially extrasphincteric. Once an infection has reached one of these three posterior spaces, the process has a virtual free pathway to either or both ischioanal fossa—hence the pathogenesis of the horseshoe abscess. Suppurative processes originating in the abdomen or pelvis may dissect in the retro-rectal space. Once there, it has direct access to the ischioanal fossa via Alcock’s canals bilaterally.

Effective evaluation of patients with anorectal infections requires an attentive history, which results in a directed physical examination. Inspection is the obvious first element, which may have in evidence obvious or visually imperceptible pathology. Bi-digital examination of the rectum confirms or excludes processes above the sphincters and/or the ischioanal fossa. An important component of the digital rectal examination includes palpation of the intersphincteric grove. This landmark physically is the step off palpable between the internal sphincter and the subcutaneous component of the external sphincter. It is a surrogate landmark for the dentate line within a 1–2 mm approximation. The originating crypt may be palpable on in this region. Pressure applied over the fluctuant process may decompress purulence into the offending crypt, which facilitates a definitive identification of the abscess and fistula. Examination of the rectum with either rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy may be appropriate in selected cases where diagnostic uncertainty exists. All cases with perianal/perirectal necrosis should have an evaluation of the rectum as well as those demonstrating purulent drainage per rectum.

Imaging in Acute Anorectal Infection

Adjunctive imaging in the setting of cryptoglandular infections is rarely necessary with a careful clinical evaluation. However, it may be informative in the following settings:

Suspicion of an intersphincteric abscess

Patients with fluctuance or suppurative drainage within the rectum

Evaluation of multiple space abscesses

Consideration of an abdominopelvic etiology

In cases of an inadequately drained or non-resolving infection

Figures 4.5 and 4.6 show clinical examples of selected imaging may be illustrative of the utility of imaging in acute anorectal infections.

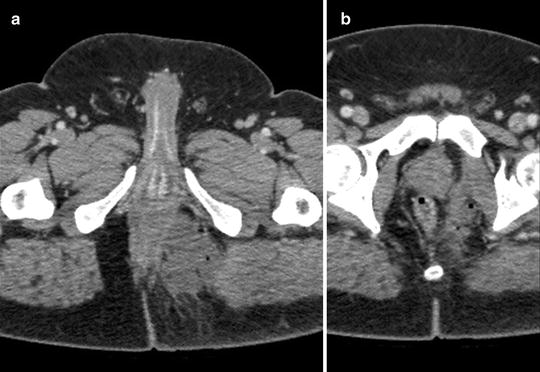

Fig. 4.5

(a) This CT scan image demonstrates fluid and gas within the sphincter complex at the level of the mid-anal canal. (b) A higher cut above the levator ani demonstrates an extensive fluid and gas collection. This scenario represents an intersphincteric supralevator abscess

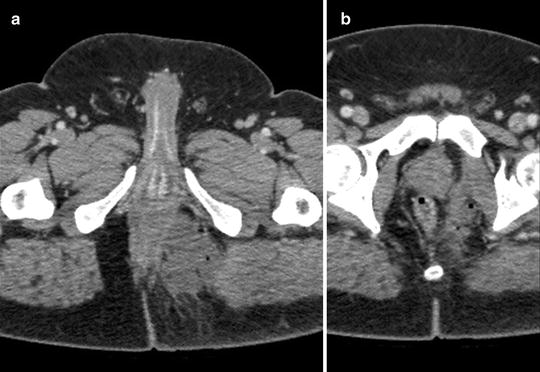

Fig. 4.6

(a) CT scan demonstrating a left-sided ischioanal abscess is in evidence. (b) A higher cut in the same case demonstrates an extrasphincteric extension of this abscess above the levators. Collectively, these two findings constitute an extrasphincteric supralevator abscess

Figure 4.7 shows the prevalence of the five types of infections based on pathway of dissemination and anatomic location. It is readily apparent that majority of infections reside distally in the perianal, intersphincteric, or ischioanal spaces (86 %) [8].

Fig. 4.7

Cryptoglandular anorectal infections occupy the perianal, ischioanal, intersphincteric, supralevator, and submucosal spaces in this order of frequency

Once supralevator infections are excluded by physical examination, it is generally acceptable to proceed with incision and drainage in the office or emergency department setting. The most important principle is to place a medial incision approximately 2.5 cm in length in a radial direction to the anal verge, which allows decompression of the suppurative process. The often-tempting impulse to place the incision over the greatest area of fluctuance may result in a very long resultant fistula. This tendency should be avoided at all cost. Instead, incision should be placed as medially as possible while still over the abscess cavity. This approach minimizes the length of any subsequent fistula. Generally speaking, antibiotics are unnecessary except in immunocompromised patients and those with locally advanced and extensive soft-tissue infections. The authors prefer radial incisions over cruciate or circumanal because of their enhanced cosmetic result, i.e., radial incisions avoid a step off deformity once healing has occurred. Intersphincteric abscess confined to the distal anal canal can be simply managed with a stab-wound incision placed at the intersphincteric groove.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree