Chapter 4 Chronic viral hepatitis

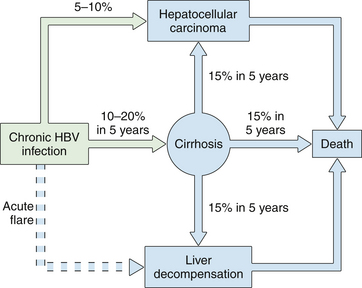

2 Long-term complications of chronic hepatitis include cirrhosis, liver failure, portal hypertension, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

3 Until recently, peginterferon plus ribavirin was the only approved treatment for chronic hepatitis C; overall more than 50% of patients treated with this dual therapy did not achieve viral eradication.

4 The direct-acting antiviral agents boceprevir and telaprevir were approved in May 2011 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin; the sustained virologic reponse rates up to 66% and 79%, respectively, with the addition of one of these two protease inhibitors to peginterferon plus ribavirin. In addition, approximately half to two-thirds of patients can achieve these high rates of viral eradication with only 24 to 28 weeks of therapy.

5 Seven drugs are approved for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B: interferon and peginterferon, three nucleoside analogues (lamivudine, telbivudine, entecavir), and two nucleotide analogues (adefovir and tenofovir); entecavir and tenofovir are the current first-line agents.

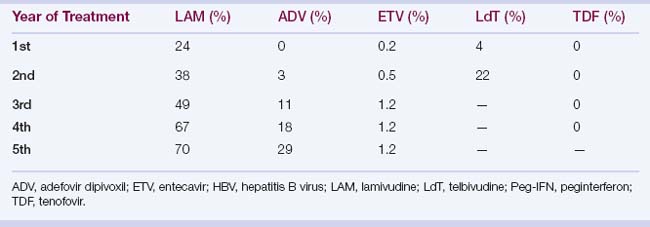

6 Hepatitis B virus mutates in response to antiviral drug treatment, which may lead to drug resistance, cross-drug resistance, and multidrug resistance; long-term treatment is required in these patients.

Overview

1. Chronic hepatitis is a condition characterized by persistent liver inflammation for more than 6 months after initial exposure or diagnosis of liver disease.

2. Causes of chronic viral hepatitis are hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus (HDV), and, in some circumstances, hepatitis E virus (HEV).

Chronic Hepatitis B

Clinical features and natural history

1. Symptoms of chronic hepatitis range from none, to nonspecific complaints (fatigue, right upper quadrant pain), to complications of cirrhosis.

2. Extrahepatic manifestations occur in up to 20% of patients with chronic hepatitis B and include arthralgias, polyarteritis nodosa, glomerulonephritis, mixed essential cryoglobulinemia, and a few other rare syndromes.

3. The risk of chronicity depends on the age and immune function when a person is infected; chronic infection occurs in

4. Approximately 25% of adults who become chronically infected during childhood will die at some point in their lifetime of HBV-related liver cancer or cirrhosis.

6. The prevalence of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) declines with age, with spontaneous loss of HBeAg in 7% to 20% of patients per year.

7. Spontaneous loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) occurs infrequently (0.5% to 1% per year); with most patients developing anti-HBs.

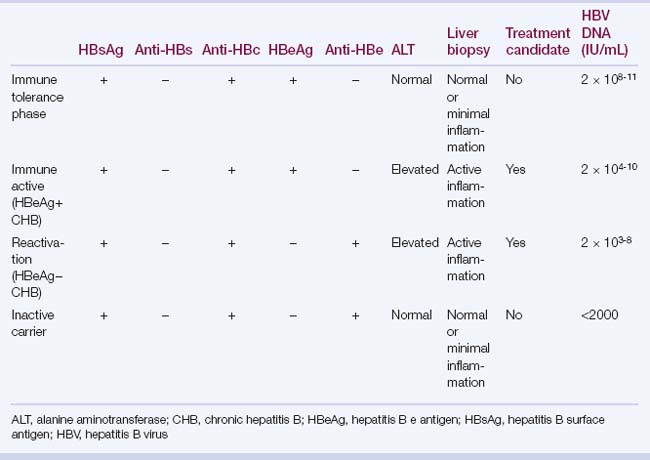

Serologic and virologic tests (see Chapter 3)

2. When HBsAg is detectable, further laboratory testing to assess disease status and need for treatment is indicated:

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT): levels can fluctuate; test ALT every 3 to 6 months if ALT is persistently normal and more often when elevated.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT): levels can fluctuate; test ALT every 3 to 6 months if ALT is persistently normal and more often when elevated.

HBeAg and anti-HBe: define the type of chronic hepatitis B (i.e., HBeAg positive or HBeAg negative) and the end point of therapy (i.e., loss of HBeAg in HBeAg-positive patients).

HBeAg and anti-HBe: define the type of chronic hepatitis B (i.e., HBeAg positive or HBeAg negative) and the end point of therapy (i.e., loss of HBeAg in HBeAg-positive patients).

Tests of liver disease severity: these include platelet count, total bilirubin, albumin, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (INR).

Tests of liver disease severity: these include platelet count, total bilirubin, albumin, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (INR).

Liver biopsy: this is optional but is helpful to determine the histologic grade and stage of disease and to identify coexistent liver diseases such as steatohepatitis, iron overload, or autoimmune hepatitis; more studies are needed to assess the role of noninvasive tests of fibrosis, such as serum fibrosis markers and transient elastography.

Liver biopsy: this is optional but is helpful to determine the histologic grade and stage of disease and to identify coexistent liver diseases such as steatohepatitis, iron overload, or autoimmune hepatitis; more studies are needed to assess the role of noninvasive tests of fibrosis, such as serum fibrosis markers and transient elastography.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT): levels can fluctuate; test ALT every 3 to 6 months if ALT is persistently normal and more often when elevated.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT): levels can fluctuate; test ALT every 3 to 6 months if ALT is persistently normal and more often when elevated. HBeAg and anti-HBe: define the type of chronic hepatitis B (i.e., HBeAg positive or HBeAg negative) and the end point of therapy (i.e., loss of HBeAg in HBeAg-positive patients).

HBeAg and anti-HBe: define the type of chronic hepatitis B (i.e., HBeAg positive or HBeAg negative) and the end point of therapy (i.e., loss of HBeAg in HBeAg-positive patients). Tests of liver disease severity: these include platelet count, total bilirubin, albumin, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (INR).

Tests of liver disease severity: these include platelet count, total bilirubin, albumin, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (INR). Liver biopsy: this is optional but is helpful to determine the histologic grade and stage of disease and to identify coexistent liver diseases such as steatohepatitis, iron overload, or autoimmune hepatitis; more studies are needed to assess the role of noninvasive tests of fibrosis, such as serum fibrosis markers and transient elastography.

Liver biopsy: this is optional but is helpful to determine the histologic grade and stage of disease and to identify coexistent liver diseases such as steatohepatitis, iron overload, or autoimmune hepatitis; more studies are needed to assess the role of noninvasive tests of fibrosis, such as serum fibrosis markers and transient elastography.Pathology and pathogenesis

1. HBV is a hepatotropic virus; most liver damage from HBV is caused by host immune responses with a cell-mediated response directed against cellular hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg).

3. Non–antigen-specific immune responses, such as those mediated by inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon), may be more important for viral clearance than CTL-mediated mechanisms.

4. A hyperactive host response may lead to fulminant hepatitis, whereas a reduced host response increases the risk of chronic infection.

6. Nonspecific histologic findings include a predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate, which may or may not be confined to the portal tracts.

7. Characteristic histologic findings of chronic hepatitis B: these include ground-glass hepatocytes in which the cytoplasm is stained pink with hematoxylin-eosin in response to massive production of HBsAg; HBcAg can be demonstrated in the hepatocyte nuclei, within the cytoplasm and on the cell membrane.

Treatment

1. Goals of treatment

Prevention of long-term complications (cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma) and mortality by durable suppression of serum HBV DNA

Prevention of long-term complications (cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma) and mortality by durable suppression of serum HBV DNA

Primary treatment end point: sustained decrease in serum HBV DNA level to low or undetectable (less than 10 to 15 IU/mL)

Primary treatment end point: sustained decrease in serum HBV DNA level to low or undetectable (less than 10 to 15 IU/mL)

Prevention of long-term complications (cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma) and mortality by durable suppression of serum HBV DNA

Prevention of long-term complications (cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma) and mortality by durable suppression of serum HBV DNA Primary treatment end point: sustained decrease in serum HBV DNA level to low or undetectable (less than 10 to 15 IU/mL)

Primary treatment end point: sustained decrease in serum HBV DNA level to low or undetectable (less than 10 to 15 IU/mL)4. Drugs

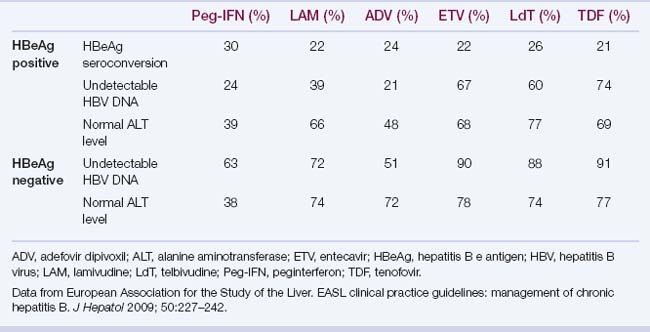

d. Rates of HBeAg seroconversion, undetectable HBV DNA, and normal ALT at 1 year of therapy are shown in Table 4.4.

e. Specific drugs

Peginterferon: Consider in young, noncirrhotic patients with low HBV DNA levels, high ALT levels, and a favorable genotype (better in genotype A > B > C > D). Treatment consists of 180 μg/week subcutaneously for 48 weeks.

Peginterferon: Consider in young, noncirrhotic patients with low HBV DNA levels, high ALT levels, and a favorable genotype (better in genotype A > B > C > D). Treatment consists of 180 μg/week subcutaneously for 48 weeks.

Advantages: finite treatment; absence of resistance; seroconversion in up to 32% of HBeAg-positive patients at 48 weeks of treatment; clearance of HBsAg in 6% of patients

Advantages: finite treatment; absence of resistance; seroconversion in up to 32% of HBeAg-positive patients at 48 weeks of treatment; clearance of HBsAg in 6% of patients

Nucleos(t)ide analogues: despite their high antiviral potency (greater than that of interferon), these drugs are not able to eradicate HBV, but they can maintain the sustained suppression of replication.

Nucleos(t)ide analogues: despite their high antiviral potency (greater than that of interferon), these drugs are not able to eradicate HBV, but they can maintain the sustained suppression of replication.

Advantages: potent; negligible adverse effects; oral administration; safe and effective at all ages; suitable for cirrhotic and HIV-coinfected patients

Advantages: potent; negligible adverse effects; oral administration; safe and effective at all ages; suitable for cirrhotic and HIV-coinfected patients

Disadvantages: lower rates of HBeAg and HBsAg seroconversion; prolonged treatment required, leading to an increasing risk of antiviral drug resistance

Disadvantages: lower rates of HBeAg and HBsAg seroconversion; prolonged treatment required, leading to an increasing risk of antiviral drug resistance

Lamivudine (nucleoside analogue): dose, 100 mg daily; potent, with low genetic barrier and high rate of resistance. The most common mutation leading to lamivudine resistance is a specific point mutation in the conserved YMDD motif of the HBV polymerase.

Lamivudine (nucleoside analogue): dose, 100 mg daily; potent, with low genetic barrier and high rate of resistance. The most common mutation leading to lamivudine resistance is a specific point mutation in the conserved YMDD motif of the HBV polymerase.

Adefovir dipivoxil (nucleotide analogue): less potent, but with higher genetic barrier and lower rate of resistance; dose, 10 mg daily; potentially nephrotoxic

Adefovir dipivoxil (nucleotide analogue): less potent, but with higher genetic barrier and lower rate of resistance; dose, 10 mg daily; potentially nephrotoxic

Entecavir (nucleoside analogue): potent antiviral activity with high genetic barrier and low rate of resistance; dose, 0.5 to 1 mg daily

Entecavir (nucleoside analogue): potent antiviral activity with high genetic barrier and low rate of resistance; dose, 0.5 to 1 mg daily

Telbivudine (nucleoside analogue); potency similar to that of entecavir, but with a resistance rate of 22% the second year of treatment; telbivudine-resistant mutations cross-resistant with lamivudine; dose regimen: 600 mg/daily; very infrequently can cause myopathy and peripheral neuropathy

Telbivudine (nucleoside analogue); potency similar to that of entecavir, but with a resistance rate of 22% the second year of treatment; telbivudine-resistant mutations cross-resistant with lamivudine; dose regimen: 600 mg/daily; very infrequently can cause myopathy and peripheral neuropathy

Peginterferon: Consider in young, noncirrhotic patients with low HBV DNA levels, high ALT levels, and a favorable genotype (better in genotype A > B > C > D). Treatment consists of 180 μg/week subcutaneously for 48 weeks.

Peginterferon: Consider in young, noncirrhotic patients with low HBV DNA levels, high ALT levels, and a favorable genotype (better in genotype A > B > C > D). Treatment consists of 180 μg/week subcutaneously for 48 weeks. Advantages: finite treatment; absence of resistance; seroconversion in up to 32% of HBeAg-positive patients at 48 weeks of treatment; clearance of HBsAg in 6% of patients

Advantages: finite treatment; absence of resistance; seroconversion in up to 32% of HBeAg-positive patients at 48 weeks of treatment; clearance of HBsAg in 6% of patients Nucleos(t)ide analogues: despite their high antiviral potency (greater than that of interferon), these drugs are not able to eradicate HBV, but they can maintain the sustained suppression of replication.

Nucleos(t)ide analogues: despite their high antiviral potency (greater than that of interferon), these drugs are not able to eradicate HBV, but they can maintain the sustained suppression of replication. Advantages: potent; negligible adverse effects; oral administration; safe and effective at all ages; suitable for cirrhotic and HIV-coinfected patients

Advantages: potent; negligible adverse effects; oral administration; safe and effective at all ages; suitable for cirrhotic and HIV-coinfected patients Disadvantages: lower rates of HBeAg and HBsAg seroconversion; prolonged treatment required, leading to an increasing risk of antiviral drug resistance

Disadvantages: lower rates of HBeAg and HBsAg seroconversion; prolonged treatment required, leading to an increasing risk of antiviral drug resistance Lamivudine (nucleoside analogue): dose, 100 mg daily; potent, with low genetic barrier and high rate of resistance. The most common mutation leading to lamivudine resistance is a specific point mutation in the conserved YMDD motif of the HBV polymerase.

Lamivudine (nucleoside analogue): dose, 100 mg daily; potent, with low genetic barrier and high rate of resistance. The most common mutation leading to lamivudine resistance is a specific point mutation in the conserved YMDD motif of the HBV polymerase. Adefovir dipivoxil (nucleotide analogue): less potent, but with higher genetic barrier and lower rate of resistance; dose, 10 mg daily; potentially nephrotoxic

Adefovir dipivoxil (nucleotide analogue): less potent, but with higher genetic barrier and lower rate of resistance; dose, 10 mg daily; potentially nephrotoxic Entecavir (nucleoside analogue): potent antiviral activity with high genetic barrier and low rate of resistance; dose, 0.5 to 1 mg daily

Entecavir (nucleoside analogue): potent antiviral activity with high genetic barrier and low rate of resistance; dose, 0.5 to 1 mg daily Telbivudine (nucleoside analogue); potency similar to that of entecavir, but with a resistance rate of 22% the second year of treatment; telbivudine-resistant mutations cross-resistant with lamivudine; dose regimen: 600 mg/daily; very infrequently can cause myopathy and peripheral neuropathy

Telbivudine (nucleoside analogue); potency similar to that of entecavir, but with a resistance rate of 22% the second year of treatment; telbivudine-resistant mutations cross-resistant with lamivudine; dose regimen: 600 mg/daily; very infrequently can cause myopathy and peripheral neuropathy5. Duration of HBV therapy with nucleos(t)ide analogues

HBeAg positive: treat until HBeAg seroconversion, and stop after consolidation period 6 to 12 months after HBeAg seroconversion.

HBeAg positive: treat until HBeAg seroconversion, and stop after consolidation period 6 to 12 months after HBeAg seroconversion.

HBeAg positive: treat until HBeAg seroconversion, and stop after consolidation period 6 to 12 months after HBeAg seroconversion.

HBeAg positive: treat until HBeAg seroconversion, and stop after consolidation period 6 to 12 months after HBeAg seroconversion.6. Resistance to antiviral drugs

d. Management of resistance (Table 4.6); roadmap for management of patients receiving oral antivirals for chronic hepatitis B (Fig. 4.2)

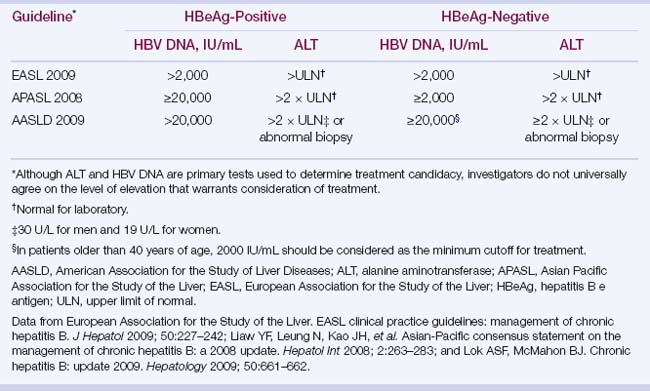

TABLE 4.3 Indications for HBV treatment

| Evidence of benefit: treatment indicated | Treatment not indicated |

|---|---|

| Decompensated cirrhotic patients | Immune tolerance phase |

| HBV DNA–positive cirrhotic patient | Inactive chronic carrier |

| Fulminant liver failure | Acute hepatitis B |

| HBsAg-positive patient who is going to be immunosuppressed | |

| Chronic hepatitis B with elevated ALT levels and HBV DNA >2000 UI/mL |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

TABLE 4.6 Management of resistance to HBV antiviral drugs

| Resistance | Rescue Therapy |

|---|---|

| Lamivudine |