Congenital and structural renal disease

- Antenatal ultrasound scanning during pregnancy detects a range of structural renal abnormalities which require assessment and follow-up during infancy.

- Urinary tract infection (UTI) is commoner in infants and children with certain structural abnormalities of the urinary tract.

- Congenital renal dysplasia is the commonest cause of renal failure in childhood.

- Genetically inherited renal diseases are most likely to present in childhood. These include autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, Alport’s syndrome and several rare tubular and metabolic disorders.

Childhood nephrotic syndrome

- In nephrotic syndrome, the glomeruli allow small proteins such as albumin to leak out into the urine.

- Childhood nephrotic syndrome commonly occurs between the ages of 1 and 5 years, in boys more often than in girls.

- The majority of children (80–85%) are responsive to steroid treatment, though many of these will have a relapsing course. Other immunosuppressive therapy may be indicated in children who relapse frequently, to minimize the side-effects of steroids.

- Most children ‘outgrow’ nephrotic syndrome by their late teens without permanent damage to their kidneys, and have an excellent long-term prognosis.

- Renal biopsy is normally reserved for those who do not respond to steroid treatment. In these children, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is the commonest histological diagnosis with a much poorer prognosis.

Glomerulonephritis

- Glomerulonephritis (GN) is an inflammation of the glomeruli and may be temporary and reversible, or it may progress of chronic kidney disease (CKD). It is usually manifest by raised blood pressure, non-visible haematuria, proteinuria and renal impairment.

- Acute post-streptococcal GN is the commonest cause, with an excellent prognosis for recovery.

- Henoch–Schönlein purpura (HSP) is frequently associated with renal involvement, though this is usually clinically mild and self-limiting. A minority may develop severe GN.

- Haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) is the commonest cause of acute kidney injury (AKI) in childhood. Full recovery is usual when associated with E. coli 0157:H7 enterocolitis and diarrhoea.

Renal replacement therapy

- In infants with renal failure, difficult vascular access and inherent cardiovascular instability mean that peritoneal dialysis, as opposed to haemodialysis (HD), is usually the modality of choice.

- Transplantation (usually possible from around 2 years of age) offers the best quality of life even though regrafting is probably inevitable at some stage.

- Living related donor transplantation is increasingly undertaken in most paediatric centres, and this facilitates pre-emptive transplantation whereby dialysis is avoided.

Introduction

Although many of the principles governing kidney disease management are common to adults and children, the underlying disease spectrum is very different, and children are more than just ‘small adults’ when it comes to diagnosis and treatment. In this chapter, we will therefore concentrate on conditions that are specific to children or where there are particular issues relating to the diseases in childhood.

Structural Abnormalities of the Kidneys and Urinary Tract

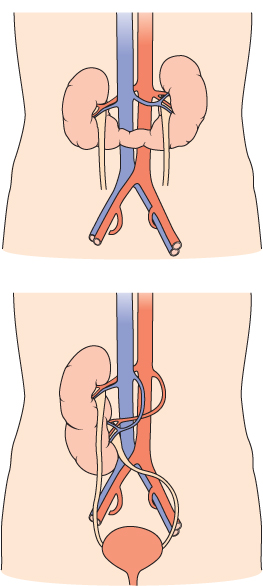

These are commonly detected antenatally (Table 12.1), usually at the 20-week anomaly scan, or in early childhood, often with urinary tract infection (UTI). Some simple examples of congenital urogenital abnormalities are shown in Figure 12.1. Some presentations of UTI are shown in Table 12.2.

Table 12.1 Antenatal abnormalities of kidneys and urinary tract

| Diagnosis | Features on antenatal scan |

| Obstruction: | |

| PUJ | Renal pelvic dilation +/− calyceal dilatation |

| VUJ | As above, with ureteric dilatation |

| PUV | As above, with distended bladder; +/− oligohydramnios |

| Cystic dysplasia | Small, bright, featureless; cysts; +/−oligohydramnios |

| MCDK | Varying size, non-communicating cysts; no parenchyma |

| ARPKD | Large, bright, featureless; +/−oligohydramnios |

| ADPKD | Large, bright; may not see discrete cysts antenatally |

| Malformation syndromes: | |

| Bardet–Biedl syndrome | Polydactyly |

| Meckel–Gruber syndrome | Syndactyly; posterior fossa brain abnormality |

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; ARPKD, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease; MCDK, multicystic dysplastic kidneys; PUJ, pelvi-ureteric junction, PUV, posterior urethral valve; VUJ, vesico-uretic junction.

Figure 12.1 Congenital urological abnormalities. a. Horseshoe kidney. b. Renal ectopia.

(Source: Adapted from Urology, with permission from Blackwell Publishing Ltd

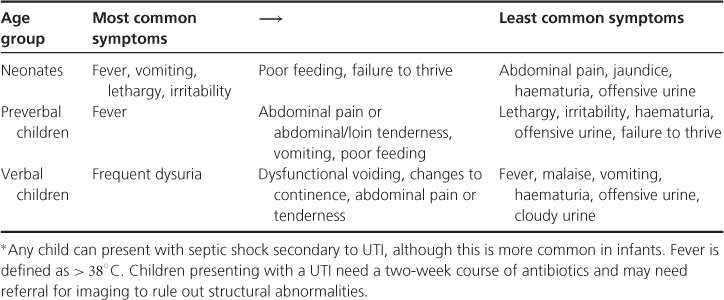

Table 12.2 Presentation of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children.

Renal Pelvic Dilatation

This is the most common finding. A fetal renal pelvis of > 5 mm in the anteroposterior diameter is generally considered abnormal, especially if it progresses on serial scans. A common approach is to start prophylactic trimethoprim at birth and perform ultrasound scans at 1 and 6 weeks after birth. If both are normal, then the infant needs no further investigation and prophylaxis can be stopped; 40–50% of postnatal scans will be normal. Severe (> 15 mm) renal pelvic dilatation (RPD), particularly if progressive and associated with intrarenal calyceal dilatation (Figure 12.2), is suggestive of obstruction, either pelviureteric junction obstruction or vesicoureteric junction obstruction if the ureter is also dilated. A Tc-99m MAG-3 (mercaptoacetyltriglycine) renogram will support the diagnosis of obstruction when there is poor drainage, and impaired function on the hydronephrotic side. Surgery (pyeloplasty or ureteric reimplantation) is likely in these cases.

The main area of debate lies in the investigation of infants with mild to moderate (5–15 mm) non-progressive RPD. Common practice includes use of prophylactic trimethoprim for at least the first year, and clinical follow-up with ultrasound monitoring of RPD, but not MCUG (micturating cysto-urethrogram); or an early MCUG and then prophylactic trimethoprim only for infants with proven VUR (vesico-ureteric reflux). In those infants who do have proven VUR, there is variation in practice over subsequent investigations.

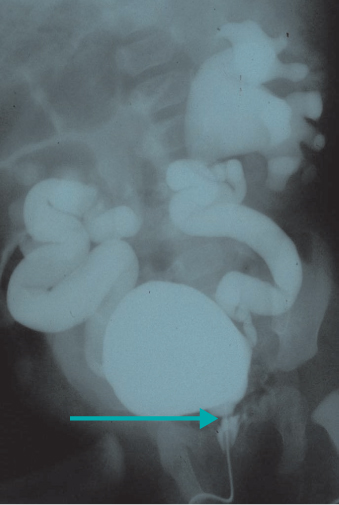

Posterior Urethral Valve

Posterior urethral valve (PUV) is an important cause of renal failure in male infants and boys. Antenatal RPD is usually bilateral, and associated with ureteric dilatation and a persistently distended bladder. In more severe cases there is cystic change in the renal parenchyma and oligohydramnios, which may lead to pulmonary hypoplasia and life-threatening respiratory failure at delivery. MCUG is essential in this clinical setting (Figure 12.3). Meticulous follow-up with combined nephrological and urological care is required. Dialysis and transplantation, and bladder augmentation surgery, may be needed.

Figure 12.3 Micturating cysto-urethrogram showing filling defect in urethra (PUV) and gross bilateral reflux with dilatation of collecting systems.