Chronic constipation is a common disorder that affects approximately 20% of the population and significantly impacts an individual’s quality of life. The diagnosis can be made using standard criteria, and in the absence of alarm signs or symptoms, a determination of the underlying etiology/etiologies should be undertaken. In many instances, these will be gleaned from the history and physical examination. Specialized diagnostic testing may be warranted after the failure of initial laxative trials. Many therapeutic classes of laxatives exist with recent analyses indicating that practicing physicians prefer to use over-the-counter therapies in lieu of more strongly evidence-based prescription pharmaceuticals.

Key points

- •

Chronic constipation is a disabling disorder affecting approximately 20% of the world’s population. In outpatient clinics in the United States it is 1 of the 5 most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal disorders.

- •

There are many etiologies for constipation and these can overlap. Constipation may be due to a combination of normal or slow transit, an evacuation disorder, or secondary to an underlying medical condition.

- •

Old and newer diagnostics are available to differentiate the causes of chronic constipation. Those most commonly used include radiopaque marker testing, anorectal manometry, balloon expulsion testing, defecography, and wireless motility capsule.

- •

Regularly used therapeutic classes include stool softeners, emollients, bulking substances, stimulant and osmotic agents, and the newest category of agents: the secretagogues.

Chronic constipation

Introduction

Chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) is one of the most common digestive complaints in the general population. This disorder affects approximately 20% of individuals, and is 1 of the 5 most common issues assessed by practicing gastroenterologists in the United States. Data recently collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey recently identified CIC as the fourth most common gastrointestinal (GI) diagnosis made in emergency departments (EDs) between 2006 and 2012. This study found 800,000 visits representing a 60% increase over this time period. Combining ED, office, and hospital outpatient visits in 2010, CIC represented 3.7 million evaluations, ranking as the fourth most commonly diagnosed GI disorder in the United States.

Although considered benign in most cases, CIC can result in chronic illness with potentially serious complications including fecal impaction, incontinence, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, bleeding, and in the most extreme cases colon perforation. These aside, the disorder alone is associated with significantly impaired quality of life. Chronic constipation is most commonly associated with increasing age. There is also increased prevalence among women (median female-to-male ratio of 1:5:1) with women more likely to use laxatives and seek health care for their constipation. Although the exact etiologic mechanisms have yet to be elucidated, anatomic and hormonal differences (ie, elevations in serum progesterone) appear to play a role. This may also explain why some women experience increased rates or exacerbations of their symptoms with pregnancy and/or during hormonal fluctuations within their menstrual cycles. Other risk factors correlated with the development of CIC include decreased daily physical activity and/or low fiber intake, low socioeconomic status, and reduced education.

Currently, CIC is defined via the Rome III criteria as documented later in this article. However, updates to these are expected with the publication of the Rome IV criteria in 2016 ( Box 1 ).

Infrequent loose stools

Insufficient criteria for a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

≥2 of the following symptoms present for ≥6 months

<3 bowel movements (BMs) per week

Lumpy or hard stools ≥25% BM

Straining ≥25% of BM

Sensation of incomplete evacuation ≥25% BM

Sensation of anorectal blockage ≥25% BM

Use of manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation ≥25% BM

Etiology/Pathophysiology

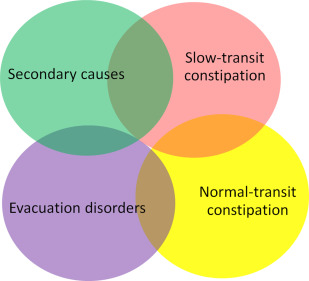

The pathogenesis of CIC is complex; it has the potential to be derived from a singular entity or multiple overlapping etiologies ( Fig. 1 ). Based on current schemata, chronic constipation is usually classified into 2 categories: idiopathic (or primary) and secondary constipation. The distinctions between the 2 types are important, as identification of etiology can help guide therapy.

Secondary Constipation

Multiple biological, environmental, and pharmaceutical precipitants exist with the potential to cause CIC ( Fig. 2 ). Pharmaceuticals are one of the most common contributors to the development of constipation. Major categories of secondary systemic disorders include endocrinopathies (eg, diabetes, hypothyroidism), metabolic abnormalities (eg, hypercalcemia or hypocalcemia, hypokalemia), neuropathic or myopathic disorders (eg, scleroderma, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disorder, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), and mechanical or pseudo-obstructions. An extensive list of potential causal factors is well described elsewhere in the clinical literature.

Idiopathic Constipation

Normal transit

Normal transit constipation is usually defined as a subtype of CIC in which adults have adequate colonic transit rates. Individuals often complain of difficult evacuation, straining, the passage of hard stools, and abdominal discomfort. Most are subsequently diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome.

Slow transit

Slow transit constipation (STC) is most commonly characterized by infrequent defecation and blunted urge to defecate due to delayed transit of fecal material through the colon. These changes have been associated with impaired colonic propulsive motor activity, delayed emptying of the proximal colon, and an attenuated gastrocolic reflex. Immunohistochemical studies have revealed a paucity of interstitial cells of Cajal. Whether this a secondary consequence of CIC or the driving factor for the development of CIC has yet to be elucidated.

Evacuation Disorders

This refers to difficulty or an inability to expel stool and is usually due to anatomic (ie, rectocele, enterocele, anal stenosis, excessive perineal descent, intussusception, rectal prolapse) or functional disorders of the anorectum. The most frequently identified of such disorders is dyssynergic defecation, which is known by many pseudonyms including pelvic floor dyssynergia, anismus, or obstructive defecation. All indicate a failure to coordinate abdominopelvic musculature leading to inadequate rectal propulsive forces, paradoxic anal sphincter and/or puborectalis muscle contraction, inadequate anal sphincter relaxation, or a combination thereof.

Chronic constipation

Introduction

Chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) is one of the most common digestive complaints in the general population. This disorder affects approximately 20% of individuals, and is 1 of the 5 most common issues assessed by practicing gastroenterologists in the United States. Data recently collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey recently identified CIC as the fourth most common gastrointestinal (GI) diagnosis made in emergency departments (EDs) between 2006 and 2012. This study found 800,000 visits representing a 60% increase over this time period. Combining ED, office, and hospital outpatient visits in 2010, CIC represented 3.7 million evaluations, ranking as the fourth most commonly diagnosed GI disorder in the United States.

Although considered benign in most cases, CIC can result in chronic illness with potentially serious complications including fecal impaction, incontinence, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, bleeding, and in the most extreme cases colon perforation. These aside, the disorder alone is associated with significantly impaired quality of life. Chronic constipation is most commonly associated with increasing age. There is also increased prevalence among women (median female-to-male ratio of 1:5:1) with women more likely to use laxatives and seek health care for their constipation. Although the exact etiologic mechanisms have yet to be elucidated, anatomic and hormonal differences (ie, elevations in serum progesterone) appear to play a role. This may also explain why some women experience increased rates or exacerbations of their symptoms with pregnancy and/or during hormonal fluctuations within their menstrual cycles. Other risk factors correlated with the development of CIC include decreased daily physical activity and/or low fiber intake, low socioeconomic status, and reduced education.

Currently, CIC is defined via the Rome III criteria as documented later in this article. However, updates to these are expected with the publication of the Rome IV criteria in 2016 ( Box 1 ).

Infrequent loose stools

Insufficient criteria for a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

≥2 of the following symptoms present for ≥6 months

<3 bowel movements (BMs) per week

Lumpy or hard stools ≥25% BM

Straining ≥25% of BM

Sensation of incomplete evacuation ≥25% BM

Sensation of anorectal blockage ≥25% BM

Use of manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation ≥25% BM

Etiology/Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of CIC is complex; it has the potential to be derived from a singular entity or multiple overlapping etiologies ( Fig. 1 ). Based on current schemata, chronic constipation is usually classified into 2 categories: idiopathic (or primary) and secondary constipation. The distinctions between the 2 types are important, as identification of etiology can help guide therapy.

Secondary Constipation

Multiple biological, environmental, and pharmaceutical precipitants exist with the potential to cause CIC ( Fig. 2 ). Pharmaceuticals are one of the most common contributors to the development of constipation. Major categories of secondary systemic disorders include endocrinopathies (eg, diabetes, hypothyroidism), metabolic abnormalities (eg, hypercalcemia or hypocalcemia, hypokalemia), neuropathic or myopathic disorders (eg, scleroderma, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disorder, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), and mechanical or pseudo-obstructions. An extensive list of potential causal factors is well described elsewhere in the clinical literature.

Idiopathic Constipation

Normal transit

Normal transit constipation is usually defined as a subtype of CIC in which adults have adequate colonic transit rates. Individuals often complain of difficult evacuation, straining, the passage of hard stools, and abdominal discomfort. Most are subsequently diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome.

Slow transit

Slow transit constipation (STC) is most commonly characterized by infrequent defecation and blunted urge to defecate due to delayed transit of fecal material through the colon. These changes have been associated with impaired colonic propulsive motor activity, delayed emptying of the proximal colon, and an attenuated gastrocolic reflex. Immunohistochemical studies have revealed a paucity of interstitial cells of Cajal. Whether this a secondary consequence of CIC or the driving factor for the development of CIC has yet to be elucidated.

Evacuation Disorders

This refers to difficulty or an inability to expel stool and is usually due to anatomic (ie, rectocele, enterocele, anal stenosis, excessive perineal descent, intussusception, rectal prolapse) or functional disorders of the anorectum. The most frequently identified of such disorders is dyssynergic defecation, which is known by many pseudonyms including pelvic floor dyssynergia, anismus, or obstructive defecation. All indicate a failure to coordinate abdominopelvic musculature leading to inadequate rectal propulsive forces, paradoxic anal sphincter and/or puborectalis muscle contraction, inadequate anal sphincter relaxation, or a combination thereof.

Clinical evaluation

A meticulous history and physical examination are the most important elements of initial evaluation of patient with chronic constipation. Laboratory tests, endoscopic evaluation, and radiographic studies are not routinely recommended. These procedures should, however, be considered in patients with alarm features, such as hematochezia, weight loss, a family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, anemia, positive fecal occult blood, or acute constipation in elderly. Further diagnostic workup is recommended for patients who fail conservative treatment and the etiology of their constipation remains unknown.

History

A careful history focuses on the onset/duration of symptoms, bowel movement frequency, stool texture and caliber, straining, sensations of incomplete evacuation or mechanical obstruction, and the need for manual maneuvers to facilitate evacuation. However, no subjective symptom is sine qua none for a particular constipation subtype. The Bristol Stool Form Scale and symptoms diaries are useful adjunctive tools for defining fecal transit and overall bowel patterns. A complete medical, surgical, dietary, and medication history are key to identifying secondary causes of constipation. Prior laxative use, doses, frequency, and response are important to help guide therapy.

Physical Examination

The most valuable components of a physical examination for chronic constipation include careful inspection of the perineum and the digital rectal examination. Inspection of the perineum is performed to identify fissures, hemorrhoids, excoriations, a gaping or patulous anus, or evidence of stool leakage. An assessment for appropriate perineal descent while a patient strains also should be observed. Identification of rectal prolapse may require the patient to strain in a squatting position. Palpation of the anal canal and rectum can identify rectal masses, strictures, hemorrhoids, rectoceles, and rectal tenderness. If stool is palpated in the rectal vault, the consistency and any evidence of blood should be noted. Sphincter tone at rest, with squeeze, and bear down are defined as normal, weak, or increased. During bear down or simulating defecation, the examiner may assess abdominal push effort by placing the other hand on patient’s abdomen. A lack of anal sphincter and puborectalis relaxation, paradoxic contraction of these muscles, or poor abdominal push efforts may suggest dyssynergia.

Diagnostic Testing

Routine bloodwork, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel, and thyroid function test, are often routinely performed to evaluate for metabolic diseases. Colonoscopy is recommended in those who meet age-appropriate guidelines for colon cancer screening or in those with alarming symptoms, as previously mentioned. Routine radiographic evaluation by x-ray or barium enema has little utility when routinely obtained and should be discouraged. However, patients who have medication-refractory symptoms should be further evaluated and updated algorithms for the assessment of these individuals have been recently published by both the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG).

Physiologic Testing

Anorectal manometry

Anorectal manometry (ARM) in association with balloon expulsion testing (BET) is considered a first-line diagnostic in patients with medication-refractory CIC. It is used to evaluate the functional performance of the pelvic floor musculature. A probe (usually high-resolution or high-definition) with circumferential pressure sensors along its length and a balloon at the tip is placed across the anal canal of a patient who is positioned in left later decubitus position. This probe can then be used to measure puborectalis and anal sphincter pressures at rest, with squeeze, during a cough maneuver, and attempted defecation, rectal sensation and compliance, the presence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, which is typically absent in patients with Hirschsprung and scleroderma.

Rectal balloon expulsion test

The BET is another first-line diagnostic in the evaluation for dyssynergic defecation. The test is usually performed using a balloon filled with 50 mL water or air. However, some experts are advocating using a volume threshold consistent with a patient’s desired urge to defecate. Although there are discrepancies and a lack of standardization regarding the amount of time considered appropriate for a positive study, most physicians agree that more than 5 minutes is abnormal, with many advocating a threshold of more than 1 minute. This study is usually performed in conjunction with an ARM.

Radiopaque marker study

The radiopaque marker study (ROM) attempts to assess the rate of transit of stool through the colon to determine whether the etiology of constipation is transit related. Although many techniques are available, the simplest, the Hinton technique, uses a single capsule of 24 radiopaque markers. This is ingested on day 1 by the patient. An abdominal radiograph is obtained 120 hours later (day 6) and STC is indicated if there is retention of greater than 20% of markers. As up to 50% or patients with dyssynergic defecation may have comorbid slow transit, it is recommended to exclude dyssynergia before performing ROM testing.

Defecography

Defecography is performed by injecting contrast material into the rectum and monitoring of defecation parameters via fluoroscopy. The study is useful for evaluating potential anatomic abnormalities causing CIC. Although not recommended as an initial diagnostic maneuver, it has benefits including testing in the natural-seated position. Findings suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction, ineffective stool evacuation, and structural abnormalities (ie, rectoceles, rectal prolapse, or intussusception) can be identified on defecography. Patients with impaired mobility and embarrassment often find this examination difficult to tolerate. In addition, there is variation in quality of the test depending on operator and intraobserver bias. Recently, functional MRI has emerged as a tool to evaluate the anatomy and dynamics of the pelvic floor but this is performed in the left lateral decubitus position similar to ARM.

Wireless motility capsule

Wireless motility capsule (WMC) is a newer technology used to assess regional and whole-gut transit times. Patients who have failed or become refractory to laxative therapy and other conservative measures are candidates for WMC testing. Given the high cost and similar clinical benefit as ROM, this test is not extensively performed, but saved in many instances for use in individuals with potential global dysmotility syndromes or to evaluate for concurrent upper gastrointestinal dysmotility in patients when a colectomy for isolated STC is being considered.

Colonic manometry

Colonic manometry (CM) measures intraluminal colonic and rectal pressures to quantify colonic motor activity. In addition, CM attempts to identify complex contractile patterns in the colon at rest, during sleep, and with meals or other propagating stimuli. CM is predominately used when necessary to differentiate neuropathic from myopathic disorders. Currently, this diagnostic is relegated to large academic centers and used primarily for research purposes.

Treatment

Multiple classes of agents are currently available for treating CIC: bulking agents, stimulant and osmotic laxatives, stool softeners, emollients, secretagogues, and serotonergic agents ( Table 1 ). Each works via a specific mechanism of action. Given the array of currently available therapies and the availability of many of these agents as over-the-counter (OTC) therapeutics, it can be difficult for patients and physicians alike to choose first-line and second-line agents. In a recent survey of US gastroenterologists, 97% endorsed using an OTC therapy as a first-line agent, specifically recommending fiber (52%) and osmotic laxatives (40%) as their initial treatments of choice. Interestingly, if these failed, osmotic laxatives were used as the most common second-line intervention (46%), but there was a sharp decline in the use of fiber (6%) in favor of prescription secretagogues (24%). Recent guidelines, including the ACG monograph on the treatment of CIC and the AGA technical review on constipation, have been congruous in their recommendations and appear to echo these general practice principles.