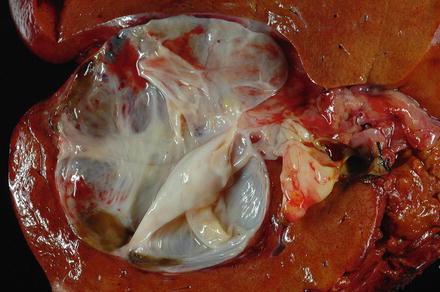

Fig. 9.1

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. This cross-section shows a multilocular cyst filled with thin watery fluid

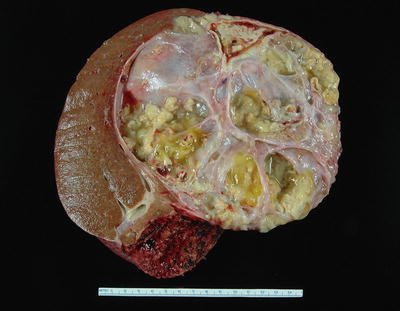

Fig. 9.2

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. This mucinous cystic neoplasm shows a multilocular cyst with a glistening inner lining

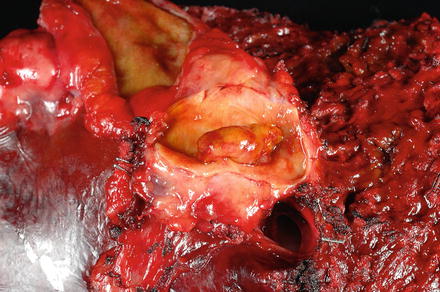

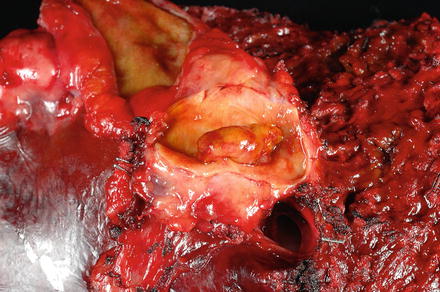

Fig. 9.3

Mucinous cystic neoplasm with invasive adenocarcinoma. The invasive adenocarcinoma in this mucinous cystic neoplasm can be seen as a solid area with papillary projections

9.2.4 Microscopic Findings

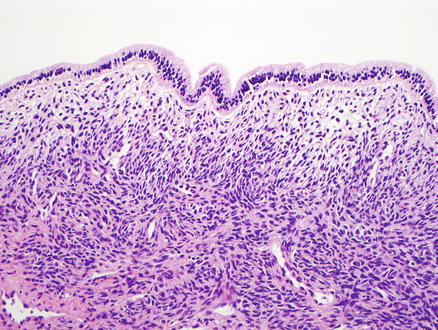

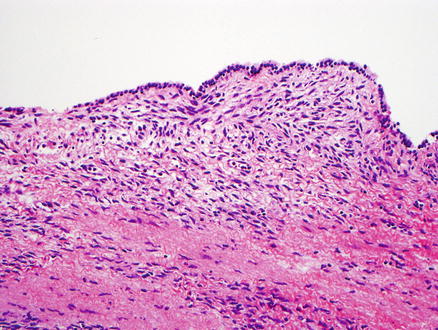

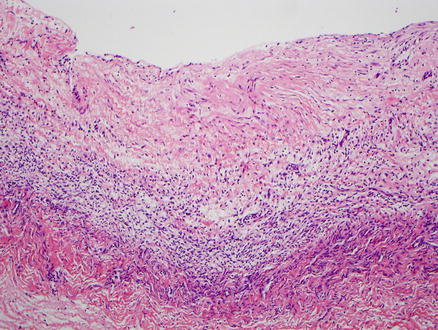

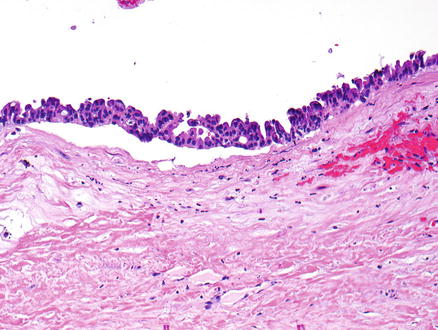

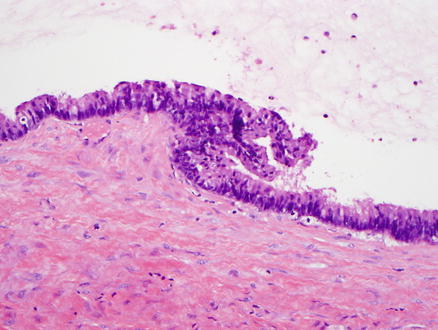

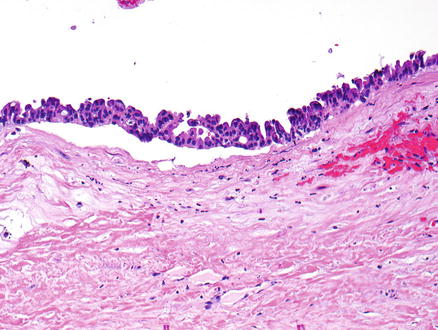

The vast majority of mucinous cystic neoplasms are found in non-cirrhotic livers. Mucinous cystic neoplasms are lined by columnar to cuboidal epithelial cells (Figs. 9.4 and 9.5) that are mucicarmine positive (Fig. 9.6). Occasionally, the epithelium may be more flattened (Fig. 9.7). The epithelium may also undergo intestinal metaplasia, with goblet cells (Fig. 9.8) and occasional Paneth cells. Gastric (Fig. 9.9) and squamous metaplasia may also occur. Scattered neuroendocrine cells are highlighted by chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostains (Fig. 9.10), but should not be interpreted as a cystic neuroendocrine tumor. Ovarian-type stroma is seen beneath the epithelium, consisting of tightly packed benign spindle cells with oval or elongated nuclei and scant cytoplasm (see Figs. 9.4 and 9.5). The presence of ovarian-type stroma defines these neoplasms as mucinous cystic neoplasms. In larger neoplasms, the stroma may become sclerotic and only small foci of residual ovarian-type stroma may be seen, sometimes with no evidence of epithelial lining (Figs. 9.11 and 9.12). In rare cases, a cystic tumor can meet all of the gross and histological criteria for a mucinous cystic neoplasm, except for the lack of ovarian stroma despite diligent sectioning and the use of immunostains [11]. These cases can be diagnosed as consistent with a mucinous cystic neoplasm after careful exclusion of other lesions.

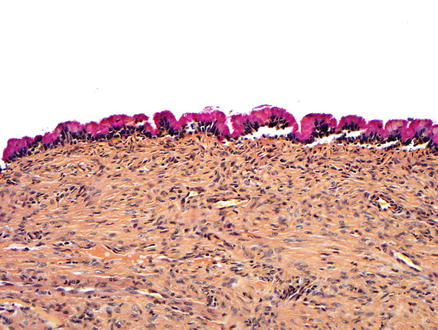

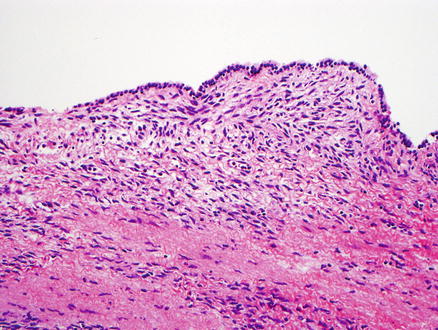

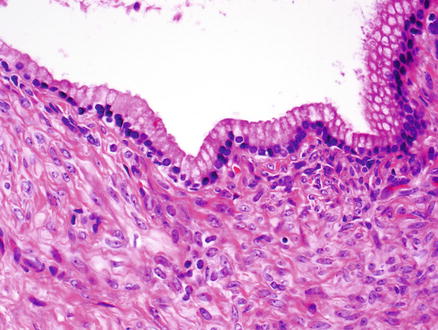

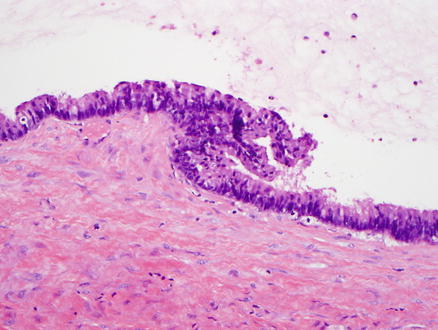

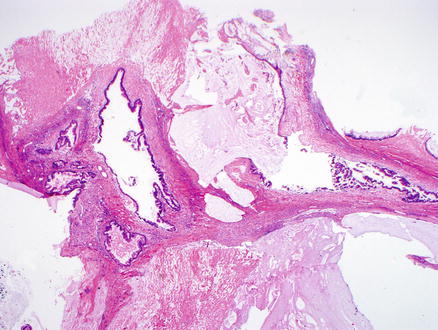

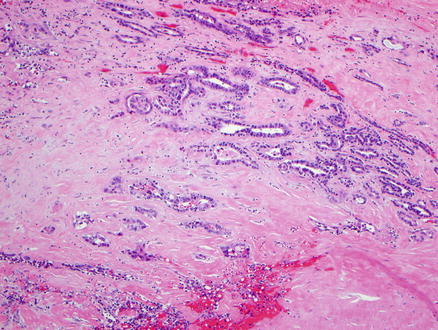

Fig. 9.4

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. This tumor is lined by tall, columnar, mucin-producing epithelial cells. Typical ovarian-type stroma is present beneath the epithelium

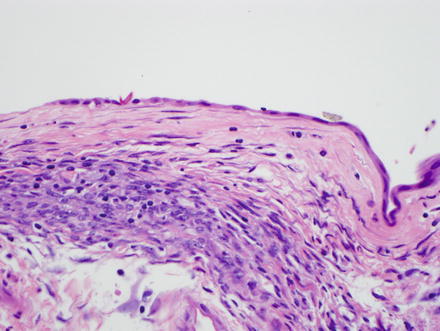

Fig. 9.5

Mucinous cystic neoplasm, low-grade dysplasia. The neoplasm has a cuboidal epithelial lining with low-grade dysplasia. Ovarian-type stroma is present beneath the epithelium

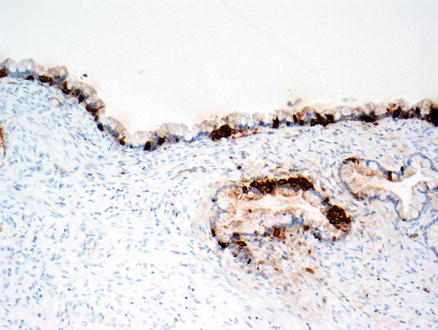

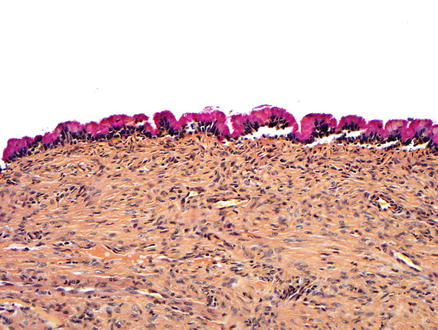

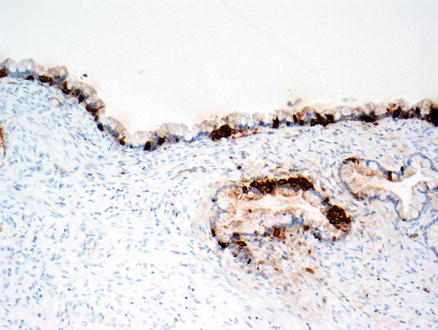

Fig. 9.6

Mucinous cystic neoplasm, mucicarmine stain. A mucicarmine stain highlights the mucin within the surface epithelium

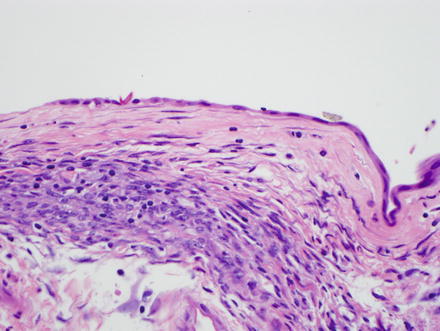

Fig. 9.7

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. Flattened epithelium lines the cyst wall of this mucinous cystic neoplasm

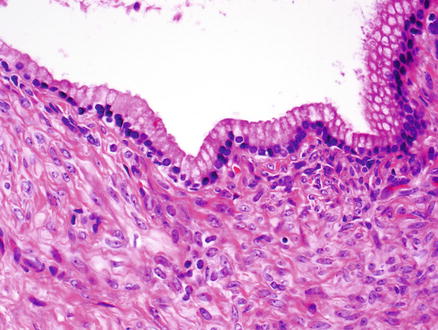

Fig. 9.8

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. Goblet cells are present within the lining epithelium of this mucinous cystic neoplasm with intermediate grade dysplasia

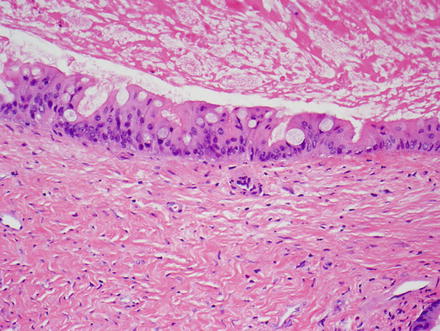

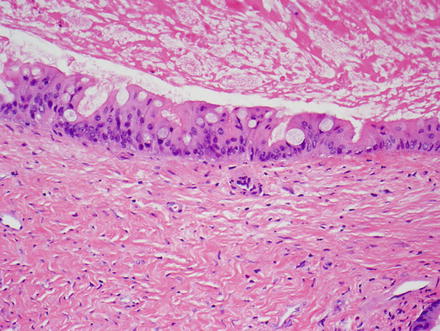

Fig. 9.9

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. Gastric-type epithelium is present

Fig. 9.10

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. A chromogranin immunostain highlights scattered endocrine cells

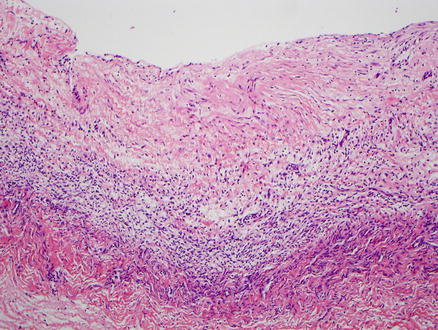

Fig. 9.11

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. No epithelium is present and the wall of this tumor is sclerotic, but identification of the ovarian-type stroma allows proper diagnosis

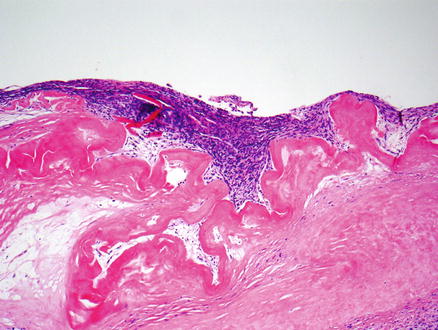

Fig. 9.12

Mucinous cystic neoplasm. No epithelium is present and the wall of this tumor is densely hyalinized, but the ovarian stroma is still identifiable

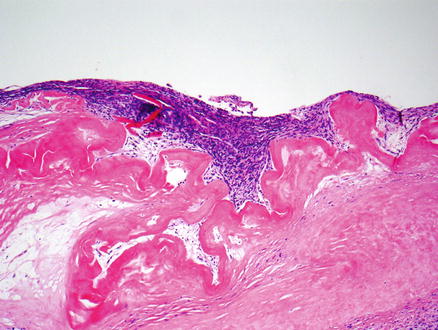

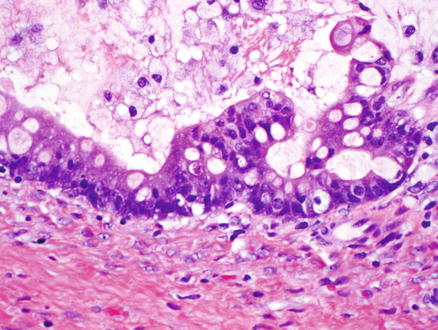

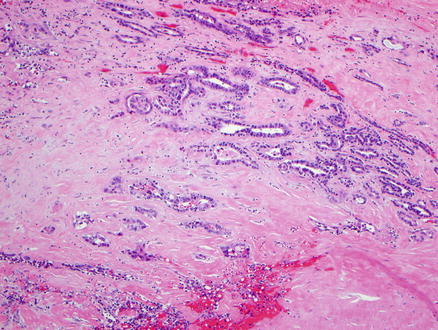

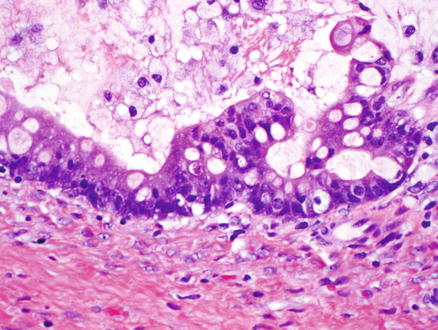

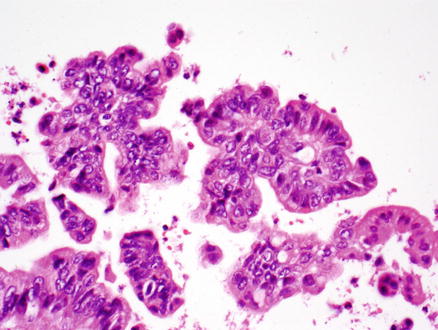

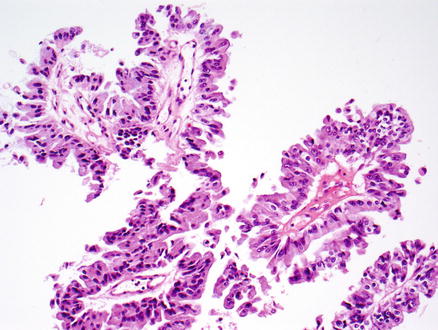

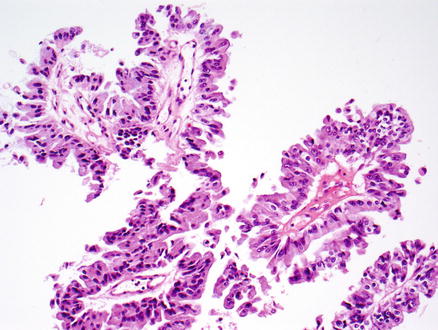

Mucinous cystic neoplasms can have varying degrees of epithelial dysplasia within the same neoplasm, but the overall classification should be based on the highest degree of dysplasia. Mucinous cystic neoplasms with low-grade dysplasia are characterized by cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells with small basally placed nuclei showing minimal cytological atypia and no mitoses (see Fig. 9.4). Papillary architecture is absent. Mucinous cystic neoplasms with intermediate grade dysplasia show mild to moderate cytological atypia with papillary projections or crypt-like invaginations into the underlying stroma and occasional mitotic figures (Figs. 9.13 and 9.14). Mucinous cystic neoplasms with high-grade dysplasia show prominent architectural and cytological atypia, with papillae, back-to-back glands and irregular budding glands, nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and easily identifiable mitotic figures (Fig. 9.15). Invasive adenocarcinoma is commonly associated with high-grade dysplasia and is usually either a ductal adenocarcinoma, showing tubular or tubulopapillary growth pattern, or a mucinous adenocarcinoma (Figs. 9.16 and 9.17). Mucinous cystic neoplasms with an associated invasive carcinoma are staged based on the cholangiocarcinoma component.

Fig. 9.13

Mucinous cystic neoplasm, intermediate grade dysplasia. Intermediate grade dysplasia is present and shows micropapillary architecture, nuclear hyperchromasia, and pseudostratification

Fig. 9.14

Mucinous cystic neoplasm, intermediate grade dysplasia. Intermediate grade dysplasia at higher magnification

Fig. 9.15

Mucinous cystic neoplasm, high-grade dysplasia. High-grade dysplasia is seen, with significant cytological atypia and loss of nuclear polarity

Fig. 9.16

Mucinous cystic neoplasm, with invasive adenocarcinoma. The invasive adenocarcinoma shows a tubular pattern

Fig. 9.17

Mucinous cystic neoplasm, with invasive adenocarcinoma. The invasive adenocarcinoma shows a mucinous pattern

9.2.5 Immunohistochemical Features

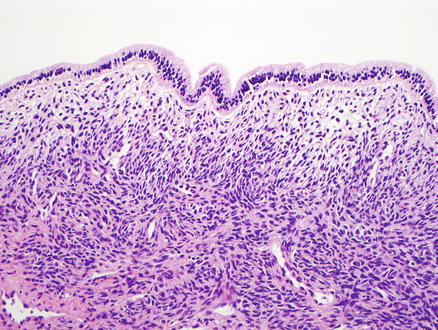

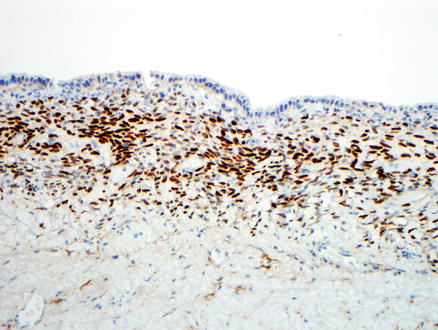

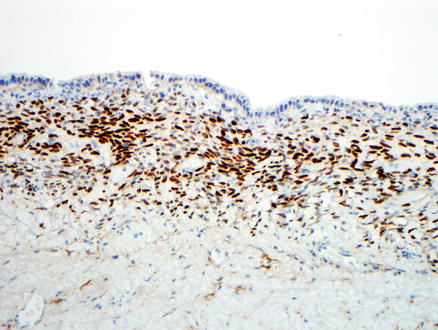

The epithelial cells express keratins, including CK7, CK8/18, AE1/AE3, and CK19, as well as other epithelial markers, such as epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen. The ovarian-type stroma expresses vimentin, smooth muscle actin, CD10, progesterone receptor, and estrogen receptor (Fig. 9.18). Immunostains are often not needed to make a diagnosis of mucinous cystic neoplasm, but the estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor stains may be useful in highlighting the presence of scanty ovarian-type stroma and confirming the diagnosis of mucinous cystic neoplasms.

Fig. 9.18

Ovarian-type stroma. An immunostain for estrogen receptor is positive in the stroma

9.2.6 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for mucinous cystic neoplasms includes intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile ducts. Both mucinous cystic neoplasms and intraductal papillary neoplasms form mucin containing hepatic cysts. However, intraductal papillary biliary neoplasms communicate with the bile ducts, do not have ovarian-type stroma, and do not have the female preponderance of mucinous cystic neoplasms.

Endometriotic cysts can also be in the differential. Mucinous cystic neoplasms have a mucinous epithelium with ovarian-type stroma, while the endometriotic cysts have a non-mucinous endometrial epithelium with an endometrial-type stroma. Immunohistochemical stains can help in their distinction, including estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, CD10, and alpha-inhibin. Endometriotic cysts are positive for estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor in both the epithelium and stromal cells, while in mucinous cystic neoplasms, only the stromal cells are estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive. In addition, the stromal cells in endometriotic cysts are CD10 positive and alpha-inhibin negative while the stromal cells in mucinous cystic neoplasms are alpha-inhibin positive and CD10 negative [12].

The differential diagnosis for mucinous cystic neoplasms can also include a simple biliary cyst. However, simple cysts are unilocular cystic lesions that are lined by biliary epithelium and lack ovarian-type stroma. Microcystic serous cystadenomas of the liver are exceedingly rare but should also be considered in some cases. They can be differentiated from mucinous cystic neoplasms by their lack of ovarian-type stroma and by their growth pattern, which is characterized by small locules lined by a single layer of non-mucinous, glycogen rich, cuboidal epithelial cells with clear cytoplasm. Biliary adenofibroma might also enter the differential in some cases, but this is a predominantly solid tumor with some microcystic spaces formed by biliary cysts. The cysts are formed by non-mucin secreting tubulocystic structures lined by biliary epithelium and are embedded in a moderately cellular non-ovarian fibrous stroma.

9.3 Intraductal Papillary Neoplasm

9.3.1 Definition

Biliary intraductal papillary neoplasms show cystic change of the bile duct with an associated papillary proliferation of atypical bile duct epithelium and form grossly visible lesions. In the past, these lesions have been referred to as biliary papillomatosis, biliary papilloma, mucin secreting biliary tumor, and biliary intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.

Biliary intraductal papillary neoplasms can have low-grade dysplasia, intermediate-grade dysplasia, or high-grade dysplasia. Some cases of intraductal papillary neoplasm also have an associated invasive carcinoma. Overall, these lesions are considered analogous to intraductal papillary neoplasm of the pancreas. They are characterized by communication with the hepatic ductal system and lack an ovarian-type stroma.

9.3.2 Clinical Features

Intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile ducts account for 10–15 % of bile duct tumors, though the frequency appears to be highest in Asia. These tumors occur in males more frequently than females, with a male to female ratio of 3:2 to 2:1. The mean age at presentation is about 65 years [13–16]. Common clinical manifestations are right upper quadrant abdominal pain, recurrent episodes of acute cholangitis and obstructive jaundice. Some patients may be asymptomatic.

Biliary intraductal papillary neoplasms have two major risk factors, especially in studies from Taiwan and Korea: hepatolithiasis and Clonorchiasis [17, 18]. Other risk factors include primary sclerosing cholangitis and choledochal cysts. A recent study has suggested that intraductal papillary biliary neoplasms might arise from the biliary tree stem/progenitor cells located in the peribiliary glands [19]. There are no known associations with genetic syndromes.

Overall, between 40 and 80 % have an invasive carcinoma on microscopic examination [20]. Elevated serum CEA may be seen in patients with adenocarcinoma (about 25 %), but elevations are not a highly sensitive or specific marker of invasive adenocarcinoma. The serum CA19-9 may be elevated in both benign and malignant lesions [17].

When intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile ducts are surgically resectable, the prognosis is excellent when there is no invasive component [21]. An invasive carcinoma leads to a worse prognosis in some but not all studies, with survival being dependent on the tumor stage [15, 22]. Overall, there have been no significant differences in patient survival for the different epithelial subtypes (see microscopic findings), although it appears that invasive carcinoma is more frequently seen in the gastric and pancreaticobiliary subtypes [15, 18]. However, one study has suggested that invasive carcinomas arising from pancreaticobiliary-type epithelium have a worse clinical outcome when compared with the other types [18].

9.3.3 Gross Findings

The background liver is typically non-cirrhotic. Intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile ducts have three major gross patterns [6, 23, 24]. The first is called duct ectasia (approximately 40 % of cases), where the neoplasm obstructs the duct, leading to obstruction and ectasia upstream of the obstruction. Secondly, the lesion can form a simple cyst within the bile duct (approximately 30 % of cases) or a multilocular cyst (approximately 30 % of cases). The epithelial neoplasm itself appears as single or multiple reddish-tan to yellow, friable, papillary lesions within the lumen of the lesion (Fig. 9.19). While duct communication is a key feature, the actual connection may occasionally be difficult to find. In one large study, bile duct communication could not be demonstrated in 7 of 109 cases [6].

Fig. 9.19

Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct. The tumor can be seen within a dilated bile duct lumen

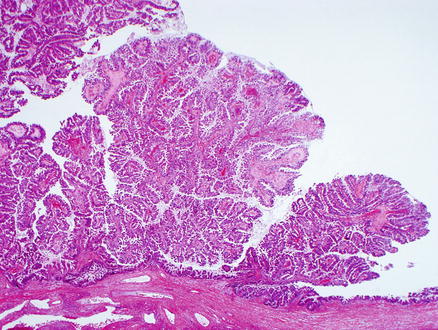

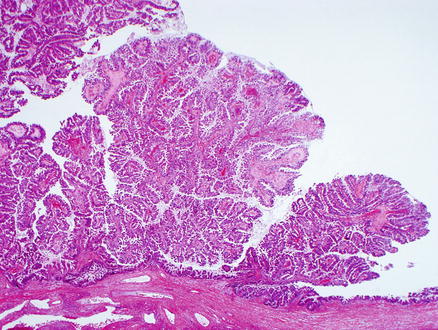

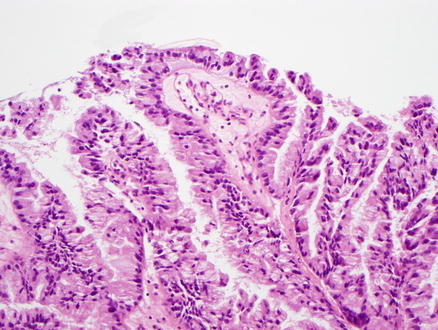

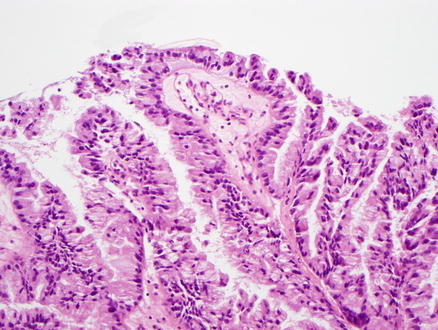

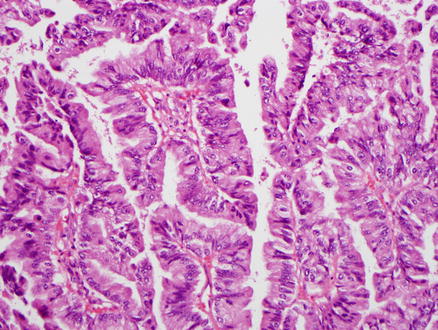

9.3.4 Microscopic Findings

Intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile ducts are characterized by papillary proliferations of biliary epithelium with delicate fibrovascular stalks (Fig. 9.20). The neoplastic epithelium has four epithelial subtypes: pancreaticobiliary (approximately 60 % of cases), oncocytic (approximately 15 %), gastric (approximately 15 %), and intestinal (approximately 10 %) [16, 25]. If there is a mixture of different epithelial subtypes within the same tumor, then the predominant component is used for subtyping. Ovarian-type stroma should not be present.

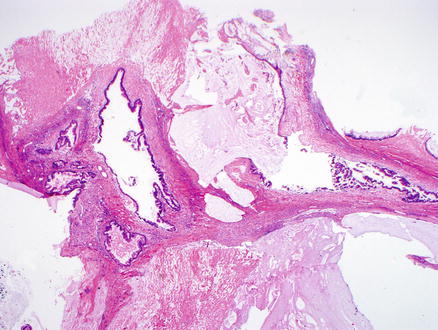

Fig. 9.20

Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct. The papillary projections are easily seen on low power magnification

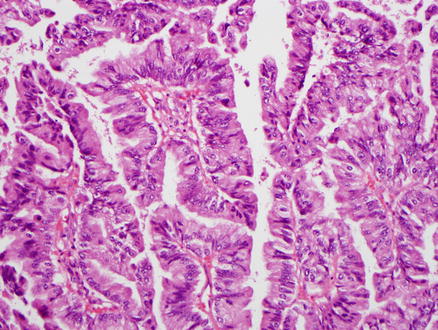

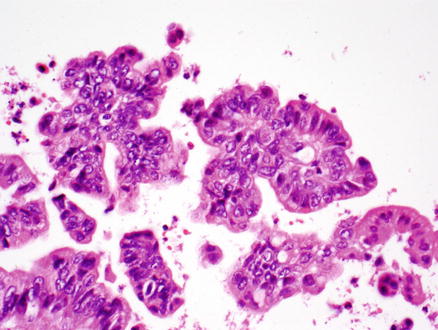

All intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile ducts show dysplasia, which may be low-grade, intermediate-grade or high-grade dysplasia, based on the degree of cytological and architectural atypia (Figs. 9.21, 9.22, and 9.23). There can be varying degrees of dysplasia within the surface epithelium in the same neoplasm, but the tumor should be graded according to the highest grade of dysplasia.

Fig. 9.21

Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct, low-grade dysplasia. This pancreaticobiliary-type epithelium shows tall columnar cells with mild atypia

Fig. 9.22

Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct, intermediate grade dysplasia. The epithelium shows nuclear pleomorphism and nuclear crowding

Fig. 9.23

Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct, high-grade dysplasia. The epithelium shows marked nuclear pleomorphism and loss of nuclear polarity

The pancreaticobiliary type shows cuboidal or columnar cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, round nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and little mucin (Fig. 9.24). This type usually has a complex papillary architecture. It also tends to be MUC1 positive and MUC2 negative (Table 9.1). The pancreaticobiliary type has the highest incidence of invasive adenocarcinoma, with more lymph node metastases, and a worse clinical outcome [18]. Most adenocarcinomas are tubular or mucinous.

Fig. 9.24

Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct. The epithelium is of the pancreaticobiliary type

Table 9.1

Mucin core protein expression in the different epithelial subtypes of intraductal papillary neoplasms

Histologic subtype | MUC1 | MUC2 | MUC5A | MUC6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Pancreaticobiliary | + | − | + | + |

Intestinal | −

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|