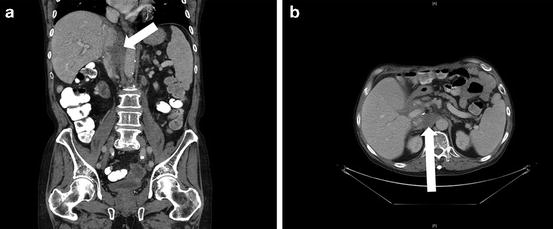

Fig. 14.1

Metastatic cholangiocarcinoma to the liver

Fig. 14.2

Retroaortic/retrocaval recurrent cholangiocarcinoma

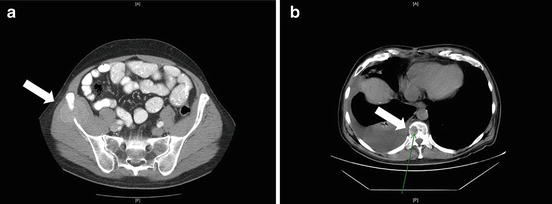

Fig. 14.3

Lytic metastases to the (a) iliac bone and (b) spine

Fig. 14.4

Pulmonary metastatic cholangiocarcinoma

Pathologic confirmation is not always necessary for cholangiocarcinoma in the native liver [14]. With recurrent cholangiocarcinoma, however, the differential diagnosis includes metastatic adenocarcinomas of other origins. Brush cytology and fluorescence in situ hybridization are useful tools in the differential diagnosis of primary cholangiocarcinoma [1]. Although these modalities are useful for lesions in the biliary tree, they are rarely of help in the diagnostic work-up of recurrent cholangiocarcinoma elsewhere.

Staging for cholangiocarcinoma was designed to assess outcome with resection. Recurrent cholangiocarcinomas, however, belong to stage IIIB for adenopathy or stage IV for distant metastases.

14.2 Prevention of Recurrence

Initial results with liver transplantation for cholangiocarcinoma, including incidental tumors, were poor due to early recurrence in the lungs, bone, liver, and skin [15, 16, 17]. The 1-year survival was as low as 36 %, and the 5-year survival was 5–38 %, similar to survival rates of patients who underwent palliative treatments [18–23]. Cholangiocarcinoma is extremely rare in the pediatric population with PSC; in children, as in adults, the posttransplant prognosis is poor [24]. Therefore, known cholangiocarcinoma is still considered a contraindication to liver transplantation [3, 25], unless transplantation is performed as part of a multimodal approach [23, 26]. An analysis from the Cincinnati Transplant Tumor Registry database showed 84 % tumor recurrence rate at 2 years [23]. Results were poor even with incidental tumors, which are often relatively small in size at the time of transplant [27]. The finding of poor survival has recently been disputed, as a small group of patients with solitary intrahepatic tumors <2 cm had excellent post-LTX patient survival in one study (73 % at 5 years) [28]. Mixed hepatocellular carcinoma–cholangiocarcinoma tumors seem to have a slightly better prognosis than cholangiocarcinoma [29, 30], although recurrence rates in mixed tumors are 70 % at 5 years [31]. These tumors should be approached and treated like cholangiocarcinoma; resection and LTX yield comparable results [32].

To improve the outcomes after LTX, every attempt has to be made to minimize tumor recurrence . Protocol driven multimodality therapies have improved the outcomes of LTX for cholangiocarcinoma, but the optimal regimen that provides best outcomes is still in evolution. Pretransplant photodynamic therapy, delivered by an endoscopic intrabiliary approach, may offer local tumor control pretransplant, and this may be an alternative to brachytherapy prior to liver transplant [33]. Multimodality therapies , starting before transplant, have resulted in lower recurrence rates and better survival, equivalent to transplantation for other liver diseases in few reported series [34, 35].

One of the widely used cholangiocarcinoma protocol was developed by the invetsigators from the Mayo Clinic. The Mayo protocol is designed for patients with biopsy-proven cholangiocarcinoma or malignant-appearing strictures by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP ) with positive brushings for cytology and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization or with CA 19-9 >100 U/mL or a malignant-appearing stricture and tumor on imaging. Exclusion criteria included intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, extrahepatic disease, a history of biopsy, attempt at resection, or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography [36]. The Mayo protocol starts with external beam radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil) for 4 weeks, followed by brachytherapy via probes introduced by ERCP, followed by oral capecitabine. Exploratory laparotomy is performed at least 2 weeks after brachytherapy and as close as possible prior to transplantation, with sampling of the perihilar lymph nodes to exclude metastasis. In their experience, one fifth of the patients had tumor spread at exploration after utilizing this protocol. If the Mayo protocol is strictly followed, the outcomes are superior when compared with other treatment with other modalities, and similar to transplantation for nonmalignant disease, with a 5-year survival of 72–84 % [37]. These findings have been replicated by other transplant centers using the multimodal treatment approach provided the cholangiocarcinoma lesions were not >3 cm, no transperitoneal biopsy was performed, and there was no extrahepatic spread [2, 35, 38, 39]. An alternative approach is stereotactic body radiation therapy followed by capecitabine in lymph node-negative patients until liver transplantation, but experience with this regimen is limited [40].

Predictors of recurrence of cholangiocarcinoma after LTX using multimodal therapy are recipient age >45 years, pretransplant CA 19-9 >100 U/mL, cholecystectomy prior to transplant, residual tumor in explant >2 cm, mass on cross-sectional imaging before transplant, tumor grade 2 or 3 out of 4 (Edmonson), or perineural invasion. Underlying PSC, percutaneous biliary procedures, gender, and CA 19-9 prior to treatment were not associated with recurrence in the Mayo experience [41].

The University of California Los Angeles group devised a tumor recurrence predictive index, based on multifocality, perineural invasion, infiltrative growth pattern, lack of neoadjuvant therapy , history of PSC, hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and lymphovascular invasion. Recurrence-free 5-year survival was 78 % in the low-risk group, 19 % in the intermediate group, and zero in the high-risk group. Tumor size was not an independent risk factor for recurrence [42]. However, the factors heavily influencing the predictive index were based on explant pathology.

Multimodal treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma leads to better patient survival than resection in select patients [43–45]. However, in the Mayo Clinic experience, results were superior with cholangiocarcinoma arising in the setting of PSC but not in de novo cholangiocarcinoma, where recent results with resection have improved [46]. There is increasing evidence to suggest that liver transplantation could offer long term cure to few rigorously selected patients with cholangiocarcinoma after neoadjuvant multimodal therapy [47]. Careful patient selection and protocol driven neoadjuvant treatment are critical for the best outcomes.

Current guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology state that “increasing data suggest that liver transplantation for cholangiocarcinoma can be successful in rigorously selected patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy in highly specialised centres” [47].

14.3 Orthotopic Liver Transplantation for Cholangiocarcinoma : Technical Considerations

There is no documented advantage between the two main technical options for liver transplantation with regard to the recipient cava–caval interposition and caval sparing (piggyback technique). The main difference in the technical approach is in the management of the native bile duct . An attempt should be made to resect as much native bile duct as possible in recipients with cholangiocarcinoma and/or PSC with creation of a Roux hepaticojejunostomy . In patients with known or suspected cholangiocarcinoma, an intraoperative microscopic frozen-section exam of the distal margin of the resected bile duct can confirm full resection of the cholangiocarcinoma. If there is residual disease at the margin, a Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy can be performed. Although perceived as a major procedure in addition to the transplant, it can be performed without significant additional morbidity [37, 48–51]. We prefer to perform the pancreaticoduodenectomy as a staged procedure the day after the transplant, which seems to significantly lower the postoperative complications.

The multimodal treatment adds technical difficulty to the transplant surgery, including radiation injury from brachytherapy, and inflammatory changes from endoscopic procedures or from a previous exploratory laparotomy (if the latter is part of the protocol). Therefore, LTX as part of multimodal therapy is associated with a significantly higher incidence of vascular complications, both early and late after LTX. However, limited experience suggest that these complications do not adversely impact patient survival [52].

14.4 Immunosuppression and Recurrence of Cholangiocarcinoma

Mammalian target of rapamycin (m-TOR) inhibitors , such as sirolimus and everolimus, inhibits the vascular endothelial growth factor, which may have a role in the development and spread of cholangiocarcinoma tumors. Sirolimus can induce partial remission or stabilization of disease in some patients with cholangiocarcinoma [53]. Based on this preliminary observation, it is perhaps beneficial to use an m-TOR inhibitor as part of the immunosuppression regimen after LTX for cholangiocarcinoma or after the diagnosis of tumor recurrence. In our center, we start the m-TOR the day after transplant, however, no studies to date have compared m-TOR inhibitor-based immunosuppression to other regimens in LTX for cholangiocarcinoma.

14.5 Treatment Options

Recurrent cholangiocarcinoma is associated with a poor prognosis. Treatment options for recurrent cholangiocarcinoma after LTX depend on tumor size, number, and location. Resection of recurrent cholangiocarcinoma is feasible for solitary lesions and resection can be curative for late recurrences with a favorable histology (e.g., well-differentiated tumors on histology). Palliative surgery can be contemplated for obstructive symptoms as most tumors are not amenable to surgical therapy.

External beam radiotherapy has been used for bone lesions with temporary remission. Intrahepatic recurrent lesions can benefit from radiofrequency ablation, similar to some cholangiocarcinoma lesions in the native liver, with up to 18-month posttreatment survival in one series [54]. Ablative therapies can be combined with surgery, for instance, targeted Yttrium 90 microsphere infusion followed by interval hepatic lobectomy of the allograft [55].

Chemotherapy , however, is the principal therapy for recurrent cholangiocarcinoma. Multiple agents have been used in this setting. 5-Fluorouracil was the mainstay of chemotherapy, as a single agent or combined with cisplatin, doxorubicin, epirubicin, lomustine, mitomycin C, and paclitaxel [1]. Gemcitabine is the preferred agent currently, and gemcitabine in combination with cisplatin [56] has shown better tumor control when compared to gemcitabine monotherapy [57].

14.6 Conclusion

Liver transplantation for cholangiocarcinoma remains controversial due to the high risk of tumor recurrence and related mortality. Currently, LTX is reserved for a strictly selected group of patients, where LTX is part of a multimodal treatment including neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or ablation therapies.

References

2.

3.

4.

5.

Rizvi S, Borad MJ, Patel T, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: molecular pathways and therapeutic opportunities. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:456–64.PubMedCentralCrossRefPubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree