Fig. 22.1

The impact of various factors on outcome of anal fistula surgery

The aim of this chapter is to discuss the causes of operative failure and risk factors for complications. A detailed description of the predictors of outcome for anal fistula surgery is reviewed in order to provide the surgeon with an appreciation of the fistula characteristics and patient-related factors that determine operative outcome. Furthermore the results of the various operative options available today are examined in order to provide a framework for operative decision-making.

The Impact of Fistula-Related Characteristics

Etiology of the Fistula

Anal fistulas are classified based on etiology and anatomy of the fistulous tract. Table 22.1 summarizes the various conditions that contribute to the development of anal fistula. The most common etiology of anal fistula is cryptoglandular disease caused by an infected anal gland. Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel disease, can lead to the development of gastrointestinal fistulas including anal fistula. Other etiologies include radiation, malignancy, obstetrical trauma, prior anal operations, and atypical infections such as actinomycosis and tuberculosis (Fig. 22.2a, b). Fistulas caused by such atypical infections are best treated medically and can often resolve once the infection is eradicated with surgical intervention reserved for the treatment of acute sepsis or recurrent or persistent fistulas [4–7].

Table 22.1

Etiology of anal fistula

Cryptoglandular disease |

Crohn’s disease |

Prior anal surgery |

Obstetrical injury |

Atypical infections (tuberculosis, actinomycosis) |

Radiation therapy |

Malignancy |

Trauma |

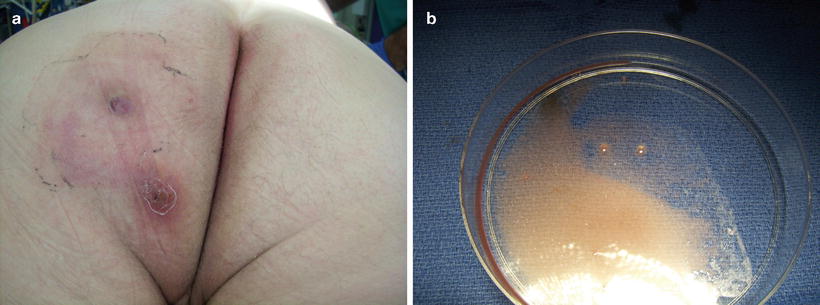

Fig. 22.2

(a) Patient with complex anal fistula from actinomycosis. (b) Silver granules noted in liquid content of fistula tract

Fistulas related to cryptoglandular disease are often single, while Crohn’s fistulas can be multiple (Fig. 22.3). The anal mucosa is normal in the setting of cryptoglandular disease. In Crohn’s disease the anal mucosa is often inflamed and/or scarred and can be associated with anal stricture, tags, and perianal skin ulceration (Fig. 22.4). Because of these findings, the surgical outcome of patients with anal fistula from cryptoglandular disease is different than those with Crohn’s disease. Mizrahi and colleagues from the Cleveland Clinic in Florida reported their results with the endorectal advancement flap in 94 patients with anal fistula [8]. The failure rate was significantly higher in patients with Crohn’s disease compared to patients with cryptoglandular disease (57.1 % vs. 33.3 %, respectively). A similar finding was published by Sonoda and colleagues from the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio [9]. A review of 99 patients who underwent the endorectal advancement flap revealed a failure rate of 50 % in Crohn’s patient compared to 23 % in non-Crohn’s patients. Pinto and colleagues investigated the impact of Crohn’s disease on rectovaginal fistula surgery results in 125 patients who were operated at the Cleveland Clinic Florida [10]. The patients underwent a variety of operative techniques. The recurrence rate of the fistula was highest in patients with Crohn’s disease (55.8 %) compared to patients with obstetrical related fistula (33.3 %) and trauma (30 %). The increased failure rate noted in patients with Crohn’s disease can be attributed to the complexity of the fistulous tract (course of the tracts and/or multiplicity), the presence of anal mucosa scarring and/or the presence of any associated stricture, and the level of disease activity.

Fig. 22.3

Patient with Crohn’s disease and multiple anal fistulas

Fig. 22.4

Patient with Crohn’s disease with anal fistula (seton in place), skin tags, and skin ulceration

In patients with active Crohn’s inflammation in the anorectal region, the placement of a non-cutting seton for drainage followed by medical therapy is the most prudent course of action. Some patients require multiple setons placement due to multiple complex tracts (Fig. 22.5). Definitive fistula repair should be deferred to a later stage after the resolution of active inflammation in order to avoid operative failure. Some patients will heal with medical therapy alone and operative intervention can be undertaken in those with persistent fistula once the mucosal inflammation subsides. The University of Calgary from Canada reported their results with Infliximab 5 mg/kg (anti-TNFα) in 29 patients with fistulizing Crohn’s disease [11]. Twenty-one patients had perianal fistulas, eight had rectovaginal fistulas, and four had combined fistulas. The selective use of seton combined with infliximab infusion and maintenance immunosuppression resulted in complete healing in 67 % of the patients with perianal fistula and a partial response with symptomatic improvement was noted in 19 % of the patients (mean follow-up of 9 months). Another study from the Cleveland Clinic Ohio reported the outcome of 218 patients with Crohn’s disease and compared patients who underwent surgery alone for anal fistula to those who received biologic immunomodulator treatment in addition to surgery [12]. Overall improvement was higher in patients who received biologic therapy (71.3 % vs. 35.9 %, p = 0.001). It is important to note that biologic treatment should be initiated only after drainage of any active perianal sepsis. A study from the University of Pittsburgh reported the outcome of 32 patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease who received infliximab [13]. Patients who underwent an exam under anesthesia with placement of a draining seton had a lower recurrence rate compared to those who received the medical therapy alone (44 % vs. 79 %, p = 0.001). Furthermore the time to recurrence was longer in patients with draining setons (13.5 vs. 3.6 months, p = 0.0001). But it is essential to keep in mind that while medical therapy can be beneficial in some patients, it is ineffective in others. Iesalnieks and colleagues from Germany reported their experience with 66 Crohn’s patients with perianal fistulas who underwent a total of 100 surgical interventions such as fistulotomy or non-cutting seton placement followed by azathioprine and/or infliximab therapy [14]. While 67 % of the patients benefited from the medical therapy, 33 % of patients failed. Predictors of poor outcome included presence of Crohn’s colitis, age at the onset disease <20 years, and higher fistulas.

Fig. 22.5

Several non-cutting setons in a patient with multiple anal fistulas from Crohn’s disease

Anatomical Classification of the Fistula

The anatomy of an anal fistula has a direct impact on the outcome of operative intervention. Anal fistula is classified based on the course of the fistulous tract and its relationship to both the internal and external sphincter muscles. The most widely accepted fistula classification is the Parks’ classification (Table 22.2). It was based on the analysis of 400 cases of anal fistulas treated over a 15-year period [15]. According to Parks and colleagues the majority of anal fistulas can be described as the following four types: (1) intersphincteric, (2) trans-sphincteric, (3) suprasphincteric, and (4) extrasphincteric. Each type has variations as reported in Table 22.2. Furthermore, some patients have combined types or horseshoe variation. Other types of fistulas that involve adjacent organs include anoperineal, anovaginal or rectovaginal, and rectourethral. Traditionally the fistula anatomy in an individual patient is determined by physical examination or delineated at time of operative intervention (Fig. 22.6). Routine imaging of anal fistula is not warranted but the selective use of radiologic studies can be helpful in patients with recurrent or complex fistulas and may decrease operative failure [16–19]. Preoperative three-dimensional ultrasound (Fig. 22.7a, b), computed tomography scan (Figs. 22.8 and 22.9), and magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 22.10) can provide the surgeon with valuable information to guide the care of patients with prior failed surgery and/or complex anatomy such as multiple fistulous openings.

Table 22.2

Parks anal fistula classification

Intersphincteric |

Simple low track |

High blind track |

High track with opening into rectum |

High fistula without a perineal opening |

High fistula with extrarectal or pelvic extension |

Trans-sphincteric |

Uncomplicated |

High blind tract |

Suprasphincteric |

Uncomplicated |

High blind tract |

Extrasphincteric |

Secondary to trans-sphincteric fistula |

Secondary to trauma |

Secondary to anorectal disease |

Secondary to pelvic inflammation |

Combined/Horseshoe |

Intersphincteric |

Trans-sphincteric |

Fig. 22.6

Two external fistulous openings in a patient with an anterior-based horseshoe fistula

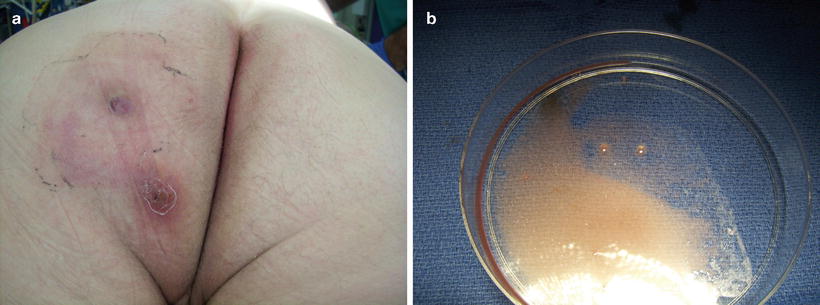

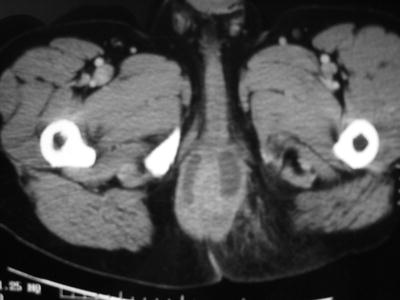

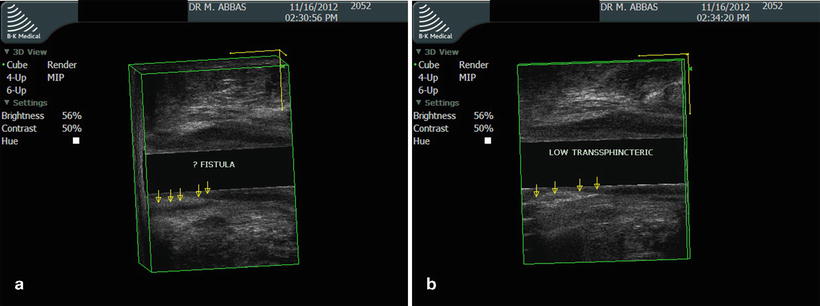

Fig. 22.7

(a) Three-dimensional ultrasound view of low trans-sphincteric fistula (sagittal view). (b) Post-hydrogen peroxide enhancement of low trans-sphincteric fistula (sagittal view)

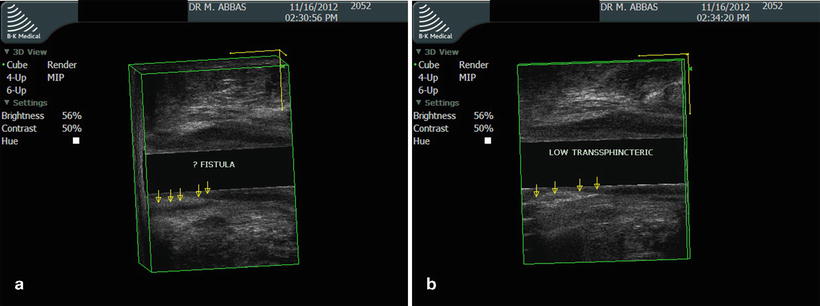

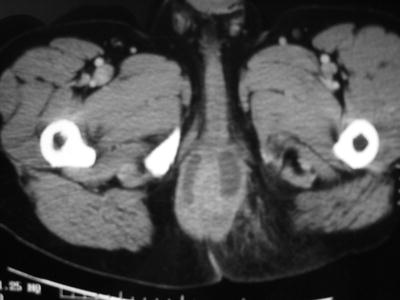

Fig. 22.8

Computed tomography scan view of patient with a posterior-based horseshoe fistula

Fig. 22.9

Computed tomography scan view of patient with right suprasphincteric anal fistula

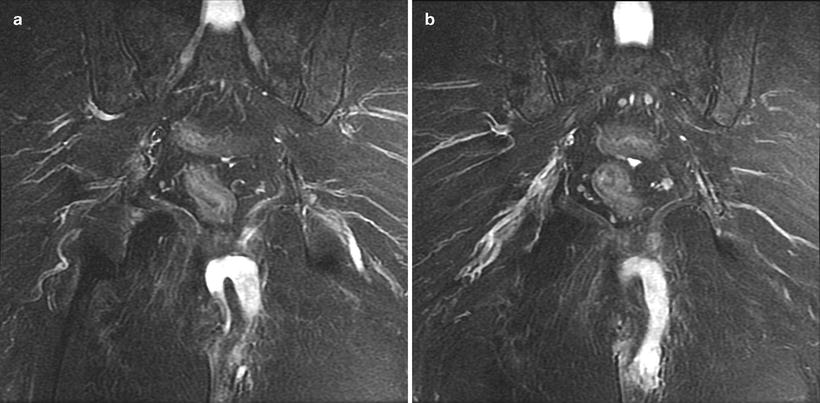

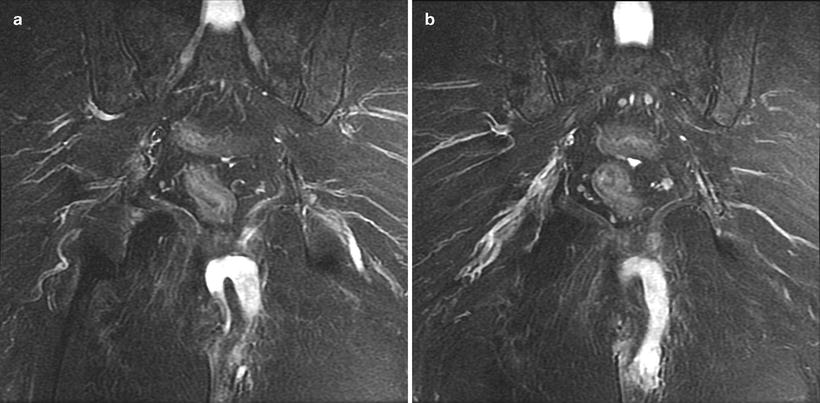

Fig. 22.10

(a, b) Magnetic resonance imaging of patient with left suprasphincteric anal fistula

Garcia-Aguilar and colleagues from the University of Minnesota reported their results in 624 patients with anal fistula [2]. The overall fistula recurrence rate was 8 and 45 % of the patients complained of some degree of incontinence after surgery. Significant differences were noted in the recurrence rate between fistula types: intersphincteric 4 %, trans-sphincteric 7 %, suprasphincteric 33 %, extrasphincteric 33 %, and unclassified 16 %. Similarly a significant difference was noted in the incontinence rate amongst the various fistula types: extrasphincteric 83 %, suprasphincteric 80 %, trans-sphincteric 54 %, unclassified 49 %, and intersphincteric 37 %. In an analysis of 179 patients treated for anal fistula at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles, a regional tertiary referral center for the 14 Kaiser Permanente hospitals in Southern California, Abbas and colleagues found similar associations between fistula type, operative failure rate, and incontinence rate [3]. The overall operative failure rate in their study was 15.6 % and de novo incontinence developed in 15.6 % of the patients. The fistula-specific operative failure rates were 0 % for subcutaneous, 9.5 % for intersphincteric, 10.7 % for low trans-sphincteric, 37.8 % for high trans-sphincteric, 27.3 % for suprasphincteric, and 44.4 % for horseshoe fistula. Fecal incontinence rate was reported for the various fistula types: subcutaneous 4.2 %, intersphincteric 10.5 %, low trans-sphincteric 7.6 %, high trans-sphincteric 40 %, suprasphincteric 55.6 %, and horseshoe 44.4 %. High trans-sphincteric and suprasphincteric fistulas were predictors of incontinence (adjusted odds ratio, 22.9 [95% CI, 2.2–242.0; p = 0.009] and 61.5 [4.5–844.0; p=0.002], respectively, compared to subcutaneous fistula). Another study from Spain reported by Jordan and colleagues analyzed the impact of fistula classification on postoperative outcome in 279 patients with anal fistula [20]. Persistence or recurrence of the fistula was noted in 7.2 % of the patients during a median follow-up of 4 months. Suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric fistulas were associated with the highest failure rates (28.1 % and 33.3 %, respectively). Similarly, the highest incontinence rates were noted in patients with suprasphincteric fistula and extrasphincteric fistula (42.3 % and 40 %, respectively). In general suprasphincteric fistula has been associated with some of the highest failure/recurrence rate and incontinence risk in numerous studies including a German study that reported the outcome of 224 patients [21]. Postoperative incontinence was noted in 43 % of patients with suprasphincteric fistula compared to 21 % of patients with trans-sphincteric fistula.

Anal fistulas that involve the vagina have been associated with a higher operative failure rate. The majority of anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas are secondary to obstetrical trauma or Crohn’s disease. In general such fistulas are more complex because of various factors including anal sphincter defects, multiple and/or higher tracts, and/or active mucosal inflammation. Several studies have compared the surgical outcome of patients with anal fistula to those with rectovaginal fistula. Abbas and colleagues from Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles reported their results with 36 patients who underwent 38 endorectal advancement flaps [22]. The overall success rate was 83 %. Patients with rectovaginal fistula had a higher failure rate compared to patients with anal fistula (67 % vs. 4 %, respectively). In a review of the Cleveland Clinic Ohio experience with 99 endorectal flaps, Sonada and colleagues noted a higher failure rate in patients rectovaginal fistula compared to those with anal fistula (57 % vs. 24 %, p = 0.002) [9]. In the previously mentioned Canadian study looking at the impact of selective use of seton combined with infliximab infusion in Crohn’s patients, complete healing was noted in 67 % of patients with anal fistula compared to 12.5 % of patients with rectovaginal fistula [11]. Löffler and colleagues from Germany reported similar findings in patients with Crohn’s disease [23]. Over a 10-year period, 147 Crohn’s patients underwent 292 operations for anorectal or rectovaginal fistula. The majority of patients had Crohn’s colitis (98 %). A higher recurrence rate was noted in patients with complex fistulas such as rectovaginal (45.6 %) compared to patients with simple submucosal fistulas (18.8 %). Furthermore the need for major operations including proctectomy was higher in patients with rectovaginal fistula compared to patients with submucosal fistula (56 % vs. 14 %, respectively).

The length of an anal fistula may also impact the outcome of surgical intervention. McGee and colleagues from Case Western University reported their experience with the anal fistula plug in 41 patients with anal fistula secondary to cryptoglandular disease [24]. The failure rate of the plug was 57 % in their study. Failure rate was higher in patients with a fistulous tract <4 cm compared to those with a tract >4 cm (79 % vs. 39 %, p = 0.004).

Prior Fistula Repair

Several studies have examined the impact of prior fistula repair on the subsequent outcome of additional operative intervention. In general, a higher failure rate has been observed in patients with prior repair. This finding is most likely due to a combination of factors: failure following the initial operative intervention may be related to the complexity of the fistula which predisposes the patient to subsequent failure and prior failure may lead to alteration of the anatomy of the fistula and the quality of tissue (i.e., more complex tracts and scarring of the anal sphincter and anal canal). Ellis and colleagues from the University of Alabama reported their experience with 95 endorectal and anodermal flaps performed between 2000 and 2003 [25]. Recurrence rate was higher in patients with a prior repair compared to those with no prior repair (43 % vs. 23 %, p < 0.03). In his review of the Cleveland Clinic Florida experience with Crohn’s-related rectovaginal fistula over a 10 year period, Pinto reported a similar finding in 125 patients [10]. Patient with no prior repair had a recurrence rate of 30.4 % compared to 47.1 % in patients with one to two repairs and 50 % in patients with more than three repairs. Comparable findings have been previously reported by another study from the Netherlands [26]. Schouten and colleagues examined 44 endorectal advancement flaps performed over a 5-year period. Patients with 1 or no prior repair had a failure rate of 13 % compared to 50 % in patients with two or more prior repairs. Similarly Nelson and colleagues from Chicago reported their results in 65 patients undergoing the island-flap anoplasty for trans-sphincteric fistula-in-ano [27]. Recurrence rate was 37 % in patients with prior repair compared to 20 % in patients with no prior repair. These findings were duplicated by Zimmerman and colleagues from the Netherlands who reported a recurrence rate of 22 % in patients with one or no previous repair compared to 71 % in patients with two or more prior repairs [28]. It is also important to note that patients with prior failed repair are at increased risk for developing fecal incontinence. A study reported by Mizrahi and colleagues from the Cleveland Clinic Florida looked at the incontinence rate in patients undergoing endorectal advancement flap [8]. The fecal incontinence rate was 5.3 % in patients with no prior repair compared to 19 % in patients who had a prior repair. Toyonaga and colleagues from Japan also reported that multiple previous surgeries were an independent risk factor for postoperative incontinence [29].

The Impact of Patient-Related Characteristics

Age

Population-based studies have reported an annual incidence of anal fistula of 6.8–10/100,000 persons with an age-specific incidence [30, 31]. Infants and children can develop anal fistula but the majority of patients present in adulthood [32–36]. Most patients present between the third and fifth decade of life [1, 30, 32–38]. The initial presentation of anal fistula includes an acute abscess, a recurrent abscess, or a chronically draining fistula. A study from Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles examined the risk of developing recurrent perianal sepsis and/or chronic fistula following one episode of acute perianal sepsis [1]. Patients younger than 40 years had greater than twofold increase in incidence of recurrent perianal sepsis compared to those 40 years or older. Based on the results of that study, it appears that young age is a predisposing factor for recurrent perianal sepsis or developing a chronic anal fistula. In addition, young age seems to increase the risk of operative failure. In their review of the Cleveland Clinic Ohio experience with anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas, Sonada and colleagues reported an association between age and operative failure [9]. In their study, the operative failure rate was 54.3 % in patients younger than 40 years compared to 32.1 % in patients between 40 and 60 years and 0 % in patients older than 60 years. It is important to note however that no difference in recurrence has been noted in other studies that have looked at age as predictor of outcome [25]. In their review of the University of Alabama’s experience with anal flap, Ellis and Clark found no difference in recurrence rate between patients younger than 40 years compared to those older than 40 years. Age can impact the functional outcome following anal fistula surgery. Abbas and colleagues analyzed the functional outcome of 179 patients operated at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles over a 5-year period [3]. Patients older than 45 years had a higher postoperative incontinence rate compared with patients younger than 45 years (adjusted odds ratio, 2.8 [95 % CI, 1.0–7.7]; p = 0.04). This finding is not surprising considering that aging can lead to weakness of the anal and pelvic floor musculature. Anal fistula surgery can further decrease baseline resting and squeeze pressure as previously demonstrated by anal manometry measurements in several studies [21, 39, 40].

Gender

Gender has been implicated as a risk factor for developing anal sepsis and chronic anal fistula. The incidence of anal fistula in males is two- to fourfold higher than females [37, 41–45]. Fistula-in-ano is uncommon in the pediatric population, but the majority of infants who present with anal fistula are males [32–36]. Interestingly a higher incidence of fistula-in-ano has been documented in male dogs compared to females [46]. It has also been observed that neutered dogs are less susceptible to develop anal fistula, raising the possibility of a hormonal influence on the pathogenesis of this condition [46]. Another proposed theory for the higher incidence of anal fistula in males is the higher sphincter tone compared to females which may contribute to duct obstruction and glandular inflammation [1].

Based on the above, it is clear that gender plays a role in the development of anal fistula but beyond the incidence of this condition, this finding has prompted many researchers to investigate the impact of gender on anal fistula surgery outcome. Hyman and colleagues reviewed the results of the prospective, multicenter outcomes registry of the New England Regional Society of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons [47]. A female gender was associated a higher failure rate (p = 0.04). While some studies have reported an association between gender and operative outcome, Ellis and Clark found no difference in fistula recurrence rate between males and females who underwent anal flap [25]. A similar finding was reported by the Cleveland Clinic Florida group when analyzing the outcome of patients who underwent advancement flap (recurrence rate 35.7 % in females and 47.3 % in males, p = NS) [8]. Van Koperen and colleagues from the Netherlands reported their results in 179 patients treated for anal fistula over an 8-year period [48]. In both groups that underwent fistulotomy or rectal advancement flap, no difference in recurrence rate was noted between genders. Garcia-Aguilar and colleagues from the University of Minnesota surveyed 375 patients who had undergone anal fistula surgery [2]. During a mean follow-up of 29 months, 45 % of the patients reported some degree of incontinence. A female gender was associated with a higher risk of incontinence.

Smoking

Smoking has been implicated as a risk factor for the development of anal fistula. A study reported from the Department of Veterans Affairs hospital in San Diego compared the risk of developing anal abscess and fistula in smokers vs. nonsmokers [49]. Smoking was associated with a significant increased risk (odds ratio 2.15, 95 % CI 1.34–3.48, p = 0.0025). Smoking has been associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications following various anorectal operations including anal fistula surgery. Zimmerman and colleagues from the Netherlands compared the outcome of endorectal advancement flap in patients who smoked vs. those who did not [50]. One hundred and five patients were followed for a median time of 14 months. Healing rate was 60 % in smokers compared to 79 % in nonsmokers (p = 0.037). In an effort to understand the effect of smoking on healing, a subsequent study by the same researchers measured blood flow during endorectal advancement flap procedures. Blood flow was significantly lower in smokers compared to nonsmokers [51]. The negative impact of smoking on healing following advancement flap repair was confirmed by Ellis and Clark from the University of Alabama [25]. The overall recurrence rate was 32.6 % in 94 patients who underwent mucosal or anodermal advancement flap. Smokers had a higher recurrence rate compared to nonsmokers (42 % vs. 19 %, p < 0.05). Schwander and colleagues from Germany reported their results with the anal fistula plug in 60 patients [52]. Smokers had a higher failure rate compared to nonsmokers (p = 0.005).

Obesity

Obesity and large body habitus present significant technical challenges to the surgeon operating on the anus. This is due to a variety of factors including deep buttock cleft, poor exposure, and difficulty with positioning the patient on the operating room table. There is a paucity of data on the impact of obesity on the outcome of anal fistula surgery. Schwandner from Germany reported his experience with 220 patients undergoing advancement flap repair of complex anal fistula [53]. Success rate was significantly different in obese [Body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2] compared to non-obese patients. In non-obese patients, recurrence rate of the fistula was 14 % compared to 28 % in obese patients (p < 0.01). In addition, the reoperation rate in the failed group was significantly higher in obese patients when compared to non-obese patients (73 % vs. 52 %, p < 0.01). Using multivariate analysis, obesity was identified as independent predictive factor of success or failure (p < 0.02).

The Impact of the Surgeon on Outcome

The surgeon has a significant impact on the outcome of anal fistula surgery. The choice of an operation and how it is technically performed by the surgeon are of paramount importance. Several operations are available to treat patients including fistulotomy, fistulectomy, anal flaps such anodermal and endorectal, ligating intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT procedure), setons, and the anal fistula plug. The selection of an operation for an individual patient should take into consideration several factors including the anatomy of the fistula, its location, its etiology, prior intervention, baseline continence function, and body habitus. Several technical variations of the available operative interventions exist and yield different success rate. Technical details and intraoperative findings can determine outcome.

Intraoperative Findings and Technical Conduct

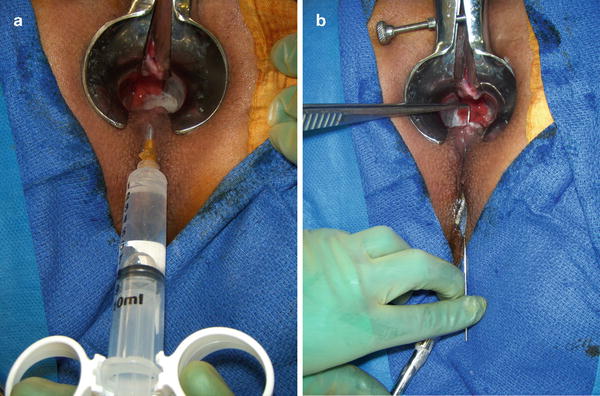

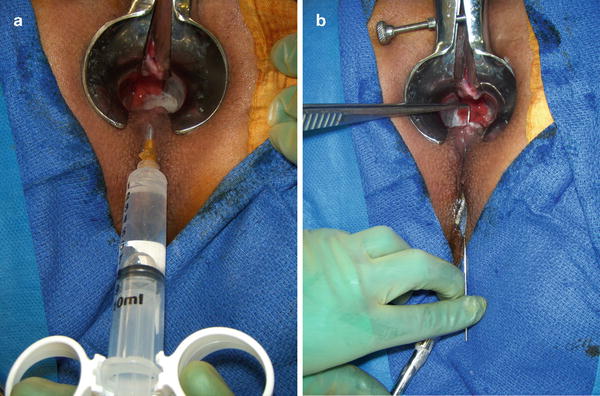

Described in simple terms, a fistula is a tunnel with two ends, an entrance and an exit. In order to successfully eradicate the fistula, the proper identification of both the internal opening (the entrance) and external opening (the exit) is necessary. This can be accomplished by probing of the fistulous tract or injecting the external opening with fluids such as hydrogen peroxide in order to identify the internal opening (Fig. 22.11a, b).

Fig. 22.11

(a) Hydrogen peroxide injection through external fistulous opening demonstrates the internal opening. (b) Probing of the tract is demonstrated

The inability to locate the internal opening is a predictor for a worse outcome. This finding has been confirmed by several studies. Sainio and Husa from Finland reported their results with 199 patients who underwent anal fistula surgery [54]. The overall recurrence rate was 11 % and the majority of the recurrences (91 %) were noted within 18 months of operation. The most common reason for recurrence was an undetected internal opening and incomplete laying open of the entire fistulous tract. Sangwan and colleagues from Pennsylvania evaluated the outcome of 523 patients with anal fistula [55]. Four hundred and sixty-three patients (89 %) were classified as simple fistula. The overall recurrence rate was 6.5 %. The recurrence was attributed to the inability to identify the internal opening in over half of the patients who recurred (53.3 %). Garcia-Aguilar and colleagues from the University of Minnesota examined the long-term outcome of 624 patients following anal fistula surgery [2]. In 4.3 % of the patients the internal opening couldn’t be determined. The overall recurrence rate was 8 %. However the recurrence rate was much higher in the subgroup of patients whose internal opening could not be identified compared to those patients whose internal fistula opening was found (56 % vs. 7 %). Jordan and colleagues from Spain evaluated the impact of various factors on anal fistula recurrence [20]. The outcome of different techniques was compared in 279 patients. Recurrence rate was highest with the procedure of coring-out the fistula with internal opening closure compared to fistulotomy which yielded the lowest recurrence rate (42.9 % vs. 1.5 %). Multivariable analysis demonstrated a significant increased risk for recurrence in patients with complex fistula (odds ratio 10.5 (CI 95 %, 1.5–74.3) [p < 0.01]) and in patients whose internal fistulous opening couldn’t be determined at time of operative intervention (odds ratio 5.3 (CI 95 %, 1–27.9) [p < 0.01]). Similarly Chi-Ming and colleagues looked at recurrence pattern in 135 Chinese patients treated for anal fistula over a 5-year period [56]. The overall recurrence rate was 13.3 % and median time to recurrence was 7.5 months. Univariate analysis identified six risk factors for recurrence including a prior history of perianal abscess and operation, complex fistula, perianal sinus, absence of internal opening, and the procedure of sinus tract excision. In logistic regression analysis, sinus tract excision was the only independent predictor of recurrence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree