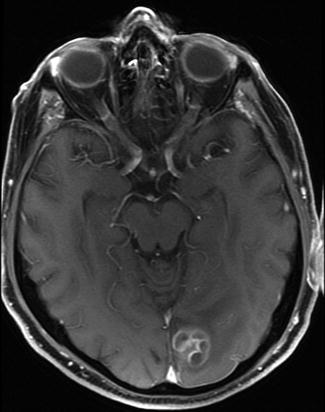

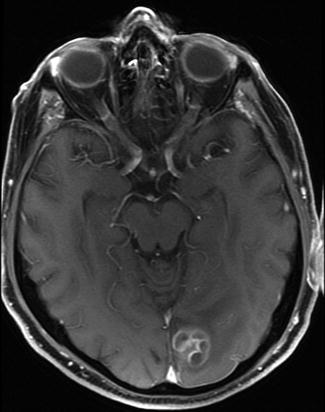

Fig. 16.1

T1-weighted, gadolinium-enhanced MRI showing a left deep-seated cystic glioblastoma

More aggressive tumour resection is also possible due to better anatomical localisation. Prior to surgery, MRI can be utilised to show fibre tracts, and functional MRI can localise eloquent areas. These images can then be fused with the guidance image and utilised intraoperatively. The use of intraoperative neuronavigation is now standard and can improve extent of resection without prolonging operative time [6].

In some centres, intraoperative CT and even MRI [7, 8] can be used to further improve the extent of tumour removal and the addition of new techniques such as 5-ALA fluorescence-guided resection shows considerable promise [9]. While there still exists significant controversy regarding the survival advantages of this, in a palliative context it does allow symptomatic improvement from cytoreduction and resolution of peritumoural oedema with decreased risk of new neurological deficit.

Occasionally gliomas can be complicated by haemorrhage causing acute deterioration. Surgical evacuation of the haematoma, if done expeditiously, can be associated with good short-term outcomes but is often avoided in view of the poor overall prognosis in this condition. As the response to adjuvant treatment improves, these attitudes are changing.

Surgery may also be indicated for palliation of epilepsy, especially in patients with low-grade gliomas that otherwise may not have required surgical intervention. This can be very effective and lead to significant improvement in quality of life [10, 11].

16.2.2 Metastases

Metastatic tumours are the most common intracranial neoplasm in adults. Autopsy studies suggest that 20–25 % of cancer patients have brain metastases [12]. Eight to ten percent of adults with cancer will develop symptomatic brain metastases [13, 14]. As treatment of the primary malignancy improves, these figures are likely to increase further. Melanoma is the most likely primary tumour to spread to the brain, but numerically most cerebral metastases are from lung or breast primaries [15]. Prior to the 1970s, surgery was rarely considered appropriate for metastatic tumours in view of the high morbidity and poor survival. Improvements in surgical technique and, in particular, imaging have changed this, and now surgery has a well-defined role. As well as providing palliation of increased intracranial pressure and neurological deficit, it can provide tissue for histology in cases where no primary site is identified and in those patients where abscess or primary malignancy are in the differential.

Surgery is usually considered in patients with solitary metastases; however, many older series are not directly comparable with current clinical practice. Older series utilising CT will underestimate the incidence of multiple metastases compared with newer studies using MRI. There is some evidence supporting the treatment of up to three metastases [16], and for palliation of raised intracranial pressure or neurological deficit, a large metastasis may be removed even if the MRI reveals other smaller asymptomatic lesions. Metastases are usually very well defined and can be macroscopically removed with modern neurosurgical techniques. This immediately reduces intracranial pressure and surrounding oedema with improvement in symptoms. This can be quite dramatic, particularly with cerebellar metastases.

Another consideration is the improvement in technique with minimally invasive approaches made possible by the routine use of neuronavigation. The decreased surgical morbidity has made resection of symptomatic metastases more acceptable. Craniotomies can be made directly over the lesion and often through a small linear scalp incision rather than a large scalp flap. The hospital stay is usually very short and the morbidity minimal.

Radiosurgery, using either a linear accelerator or the Gamma knife, is often used for the treatment of symptomatic metastases. The advantages include the ability to treat multiple lesions and the non-invasive nature of radiosurgery. The disadvantages are the limited availability, and the fact that symptoms of raised intracranial pressure may be aggravated rather than relieved in the early stages [17]. Delayed radiation necrosis is another consideration [18]. Surgery will usually provide better palliation for accessible tumours in non-eloquent areas, but radiosurgery can be very useful for treating deep-seated tumours or those in eloquent areas.

16.2.3 Meningioma

Many meningiomas are curable with simple excision, but a large number involve structures such as the dural venous sinuses or arise in relatively inaccessible areas such as the anterior foramen magnum, making complete excision impossible without unacceptable deficit. In such cases, surgical debulking may provide adequate palliation of symptoms, and the slow growth of many of these tumours often allows the residual to be treated by observation alone. When the histology is atypical suggesting a more aggressive nature, radiation therapy may be added. Surgical palliation of meningiomas may also be indicated for local control when these tumours threaten to erode through the skin.

Meningiomas are prone to haemorrhage which can be intratumoural, intracerebral or subdural, and in these instances surgery is usually indicated even if the underlying tumour cannot be completely removed [21].

16.2.4 Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus may occur in patients with primary or secondary malignancy due to obstruction of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways. Ventriculoperitoneal shunting can provide dramatic palliation of symptoms of raised intracranial pressure with minimal morbidity [22]. In some cases, where there are malignant cells in the CSF, there can be a risk of peritoneal seeding as well as increased risks of shunt blockage. In this situation, endoscopic third ventriculostomy is a minimally invasive procedure that can give similar palliation without these risks. The results in tumour patients have been reported to be similar to those in patients with hydrocephalus due to non-neoplastic causes [23].

16.2.5 Malignant Meningitis

Clinical diagnosis of malignant meningitis has become more frequent with the use of MRI [24], and it is found in up to 25 % of small cell lung cancer patients at post-mortem [25]. Malignant meningitis can cause a wide variety of neurological symptoms and signs and usually heralds a rapid decline. Some patients with malignant meningitis benefit from intrathecal chemotherapy but repeated lumbar punctures are often difficult and uncomfortable. There is also the risk of subdural or extradural injection [26]. In this situation, an Ommaya reservoir (Accu-Flo CSF Reservoir, Codman, Johnson and Johnson) can be inserted (Fig. 16.2). This is a simple procedure in which a ventricular catheter is passed, usually into the right frontal horn, and connected to a small chamber implanted permanently beneath the scalp. The incision is usually made anterior to the chamber so that the overlying scalp is numb. This makes repeated CSF access simple and much more comfortable than multiple lumbar punctures.

Fig. 16.2

An Ommaya reservoir (Accu-Flo CSF Reservoir, Codman, Johnson and Johnson)

16.2.6 Infection

Patients with malignancy are more prone to infection, and this should always be considered in patients with undiagnosed cerebral or spinal lesions, especially in patients immunocompromised from steroids or chemotherapy. Apparent metastases or glioblastomas may be cerebral abscesses from nocardia or tuberculosis (Fig. 16.3). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy can be helpful in making the distinction, but often surgery is required to confirm the diagnosis even when treatment will be medical.

Fig. 16.3

T1-weighted, gadolinium-enhanced MRI showing a left occipital enhancing mass in an 84-year-old male with no predisposing factors for infection. It was thought to be glioblastoma but histologically proven to be nocardia

16.3 Spinal

16.3.1 Metastatic

Epidural spinal cord or cauda equina compression from metastatic disease can have a significant negative effect on quality of life. Treatment by posterior laminectomy often fails, partly because the compression is often ventral. In many cases, such surgery offers little benefit over radiotherapy alone. More aggressive treatment aimed at removing ventral tumour tends to be much more invasive and requires internal fixation to maintain stability. The benefits include better neurological outcomes and improvement in spinal pain [27]. This needs to be balanced with the increased morbidity and risks of the surgery. Modern minimally invasive surgery (MIS) techniques provide a compromise better suited to palliation of pain and neurological deficit. Using a combination of neuronavigation and MIS techniques, tumours can often be decompressed through the pedicle, and fixation can then be inserted percutaneously [28]. In some cases, percutaneous fixation can be used to treat pain without neurological deficit.

Vertebroplasty can also be useful in treating pain from spinal metastases. Using percutaneous techniques, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) cement is injected through the pedicle into the affected vertebral body [29, 30]. Care must be taken to avoid injecting cement into the canal, and this technique is contraindicated if the posterior cortex is not intact. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases are uncommon and surgery would rarely be indicated. With the advent of spinal stereotactic radiosurgery, it is possible to treat these and offer some palliation [31].

16.3.2 Primary

Although benign intra-dural tumours such as ependymoma and haemangioblastoma are usually surgically removable, occasionally the surgical risks are too great, and palliative options need to be considered. Even if debulking of the tumour itself is minimal or not possible, a simple duroplasty can sometimes buy considerable time with these slow-growing tumours (Fig. 16.4). Stereotactic radiosurgery is now an additional option and can be particularly useful in patients with multiple tumours such as those with type 2 neurofibromatosis.