Chapter 3 Bilateral Thoracoscopic Splanchnotomy for Intractable Upper Abdominal Pain

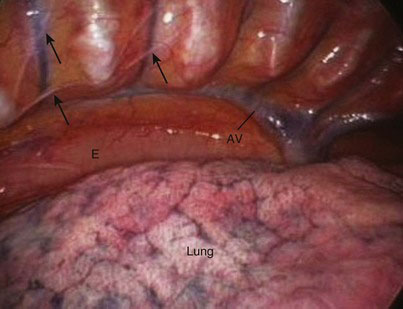

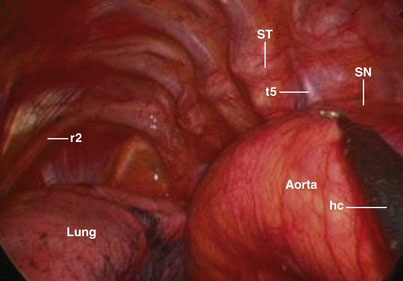

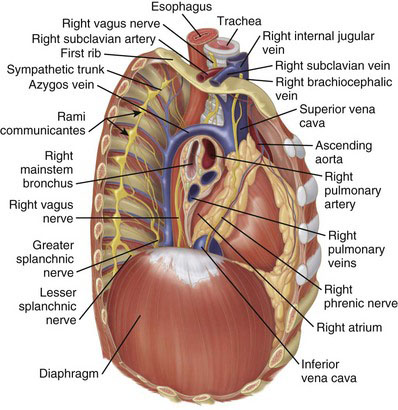

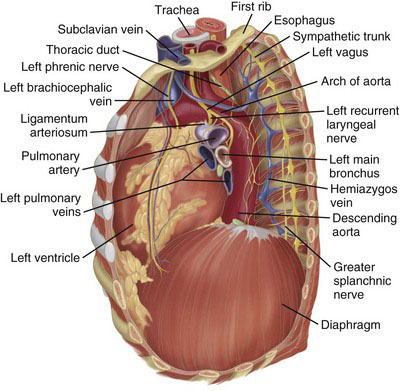

The three splanchnic nerves of the thoracic sympathetic trunk arise from the lower eight ganglia (Figs. 3-1 and 3-2). Branches of the T5-T9 sympathetic ganglia form the greater splanchnic nerve, the T10-T11 ganglia form the lesser splanchnic nerve, and the T12 ganglion forms the least splanchnic nerve. These splanchnic nerves predominantly contain visceral efferent fibers but also carry afferent sympathetic “pain” signals from the upper abdominal viscera, including the pancreas, to the brain. At thoracoscopy, these nerves can be seen running superficial to the intercostal vessels along the vertebral spine (Figs. 3-3 and 3-4), where they can readily be divided.

FIGURE 3-1 Right thoracic cavity, viewed from lateral to medial, with the lateral chest wall cut away.

FIGURE 3-2 Left thoracic cavity, viewed from lateral to medial, with the lateral chest wall cut away.

Operative indications

• Exclude alternative causes for pain. Chronic duodenal ulceration is not an uncommon coexisting disorder in chronic pancreatitis patients. It also is essential to exclude pain of drug seekers and those with psychogenic disease.

• Reserve splanchnotomy for patients who have visceral rather than somatic pain of chronic pancreatitis. Progression of pancreatitis adds a somatic component to the pain that responds poorly to splanchnotomy. Visceral pain often is described as upper abdominal, whereas back or lower abdominal pain suggests somatic pain. Bradley and colleagues described differential epidural analgesia as a potentially useful method in selecting patients with small duct chronic pancreatitis for thoracoscopic splanchnotomy; patients who responded to sympathetic block were the best candidates for splanchnotomy. Strickland and associates suggested that a favorable response to preoperative paravertebral sympathetic (splanchnic) nerve block with local anesthetic predicted a good response to splanchnotomy.

• Exclude disorders that require direct pancreatic surgery. These include pancreatic pseudocyst (internal drainage or distal pancreatectomy might bring symptomatic relief), inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas (a Beger or Whipple procedure might be necessary), and pancreatic duct dilation with or without stones (which might require a Puestow, Frey, or Beger procedure). Splanchnotomy is reserved for patients with small duct chronic pancreatitis.

• Assess severity of the pain. There is no clearly defined threshold for the selection of patients for thoracoscopic splanchnotomy. It is reasonable to reserve this procedure for patients in whom nonoperative measures have been explored and in whom pain severity has required escalating doses of opiates. Thoracoscopic splanchnotomy should not necessarily be the treatment of last resort, however, because its outcome is worst in patients with advanced chronic pancreatitis and previous pancreatic surgery. Although many of these patients may previously have received one or more celiac plexus blocks to relieve the pain with short-lived partial response, failure to achieve any response from such a block might predict poor outcome for thoracoscopic splanchnotomy.

• Ensure abstinence from drinking, which is an absolute requirement in patients with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Continued alcohol abuse predicts a poor response to thoracoscopic splanchnotomy.

• The offer of thoracoscopic splanchnotomy should be timely and not delayed if optimal quality of life is to be achieved. Patients should be selected through a multidisciplinary team discussion that involves Pain and Palliative Care disciplines and should take into account the patient’s life expectancy and fitness for a general anesthesia.

• Although thoracoscopic splanchnotomy is useful for visceral cancer pain, it is ill advised if pain is considered to be predominantly secondary to peritoneal disease, subacute small bowel obstruction, or infiltration of the abdominal wall.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree