Focal

Multifocal

Diffuse

Symptoms

Most are asymptomatic

Depends on size and number of tumors, with smaller tumors often being asymptomatic. Larger lesions can have high-output cardiac failure

Common, including, hepatomegaly, severe hypothyroidism, and rarely high-output cardiac failure

Cutaneous or visceral hemangiomas

No

Frequent

Frequent

Seen on prenatal ultrasound

Yes

Rarely

Rarely

Vascular shunting

High-flow shunts

High-flow shunts

High- and low-flow shunts

Central degeneration with necrosis and thrombosis

Common

Rare, except for larger tumors

Rare, except for larger tumors

Glut 1

Negative

Positive

Positive

Natural history

Spontaneous involution in most cases

Spontaneous involution in many cases, but many require medical or surgical intervention

Requires medical and/or surgical intervention

13.1.3 Clinical Features

Infantile hemangioma is the most common benign mesenchymal tumor of the liver in infants and children. Roughly one-third of all cases present before the age of 1 month and approximately 90 % of all tumors are diagnosed before the age of 6 months. There is a modest female predominance of about 2:1. Some tumors are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, but most are symptomatic. The symptoms may be nonspecific and include anorexia, vomiting, and failure to thrive. Other presentations include hepatomegaly, abdominal distension, respiratory failure, congestive heart failure, and the Kasabach–Merritt syndrome with consumptive coagulopathy. In a subset of cases, hemangiomas are identified in other organ sites, such as skin or viscera.

Some patients also have associated congenital anomalies, such as congenital heart disease, hydrocephalus, supernumerary digits, trisomy 21, or duplicate ureter [1]. Occasional cases of infantile hemangioma may be associated with elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein levels [2, 3].

Infantile hemangiomas generally undergo proliferation in the postnatal period, up to about 12 months of age, followed by maturation and involution over the next 5–10 years. Clinical management is based on the severity of symptoms and the size of the lesion. In general, medication therapy to relieve symptoms is the first line of therapy when treatment is needed. In patients who fail to respond to drug therapy, other effective treatments include arterial embolization, hepatic artery ligation, and surgical resection. Surgical intervention is only needed in a small proportion of cases.

13.1.4 Gross Findings

Tumors may be single or multiple (see Table 13.1) and range in size from a few millimeters to up to 15 cm. In cases with multiple tumors, the number of lesions can vary from 2 to as many as 30, frequently involving both lobes of the liver. The blood supply for the tumor varies and can derive from the hepatic artery, extrahepatic arteries, or portal vein. In general, tumors are well demarcated and nonencapsulated. Similar to hemangiomas in other locations, tumors are grossly red to tan, soft, and spongy (Fig. 13.1). Foci of hemorrhage, necrosis, and calcification can be seen, typically in larger lesions, and often in the central portion of the tumor.

Fig. 13.1

Infantile hemangioma. This tumor is diffuse and is composed of multiple soft, spongy, tan to reddish lesions

13.1.5 Microscopic Findings

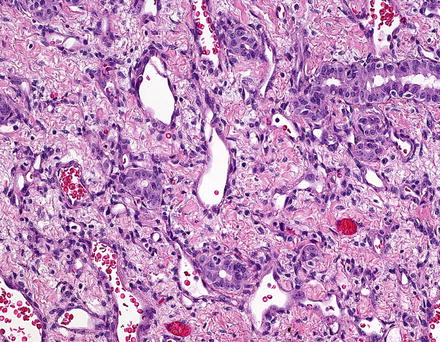

Histologically, infantile hemangiomas are composed of small, dilated, and irregular, capillary-like vascular channels lined by a single layer of flat, cytologically bland endothelial cells (Fig. 13.2). In some areas, the channels show striking interanastomosis, often with entrapped bile ducts (Fig. 13.3). Some tumors may have high mitotic activity; however, this feature does not appear to impact prognosis. Foci of extramedullary hematopoiesis may be seen, but inflammation is largely absent. The stroma is fibrous or collagenous and may be loose or dense but is generally somewhat scanty. Infantile hemangiomas do not have capsules, though larger tumors may have a rim of compressed and fibrotic liver tissue. Approximately one-third of tumors show an infiltrative border with entrapped hepatocytes and bile ducts at the periphery (Fig. 13.4). Some of the adjacent hepatocytes can be alpha-Fetoprotein positive on immunostain.

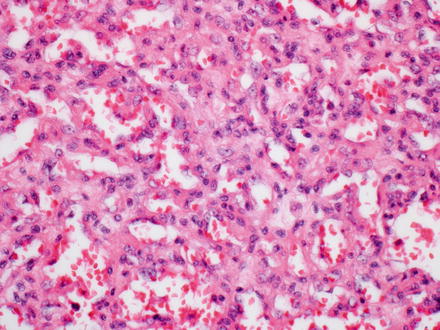

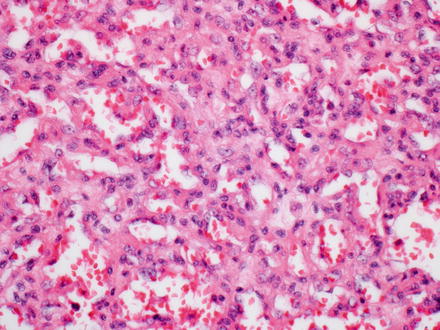

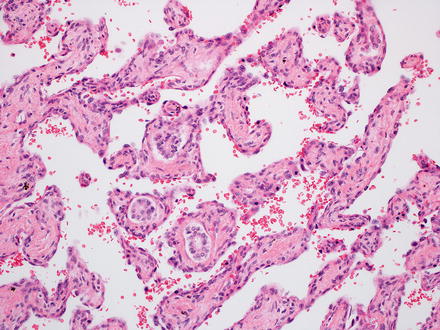

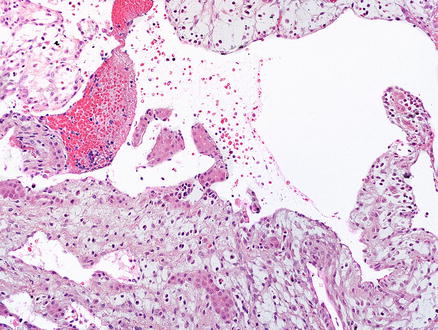

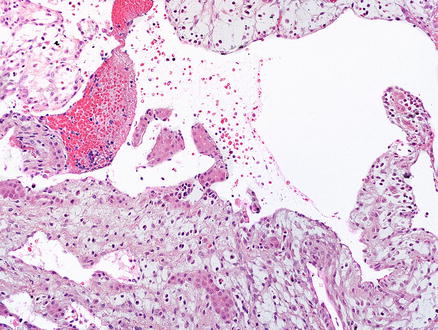

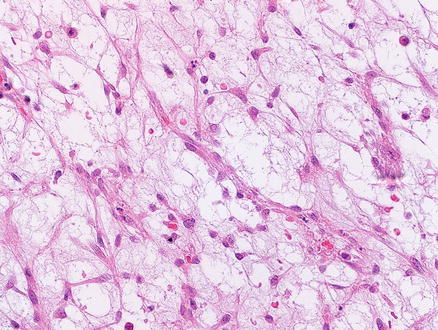

Fig. 13.2

Infantile hemangioma. The tumor is composed of medium-sized capillary-like vessels, lined by bland endothelial cells, with small to moderate amounts of intervening stroma

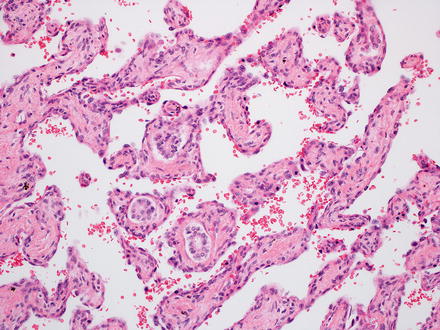

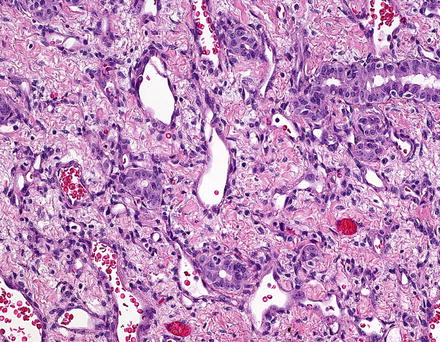

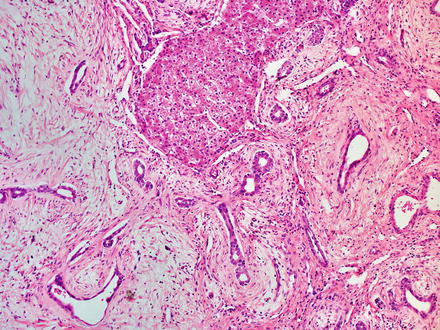

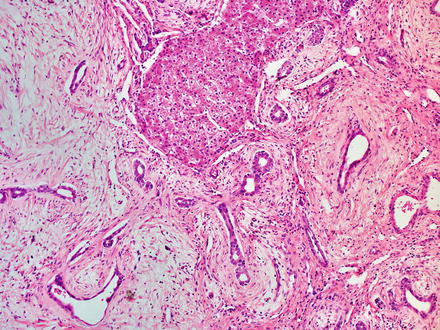

Fig. 13.3

Infantile hemangioma. The vascular channels are interconnected in this area. The fibrous connective tissue has entrapped bile ducts

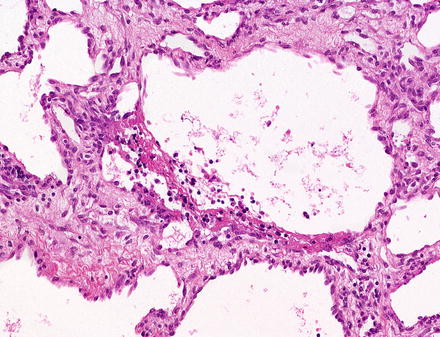

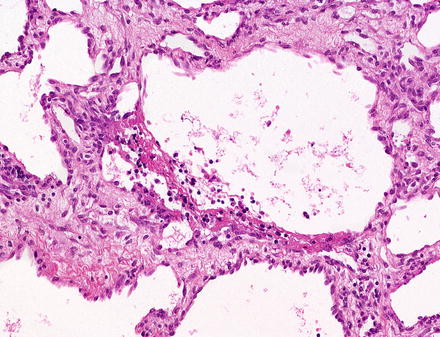

Fig. 13.4

Infantile hemangioma with entrapped bile ducts. Entrapped bile ducts can be distributed widely in the lesion, though they often appear to be more numerous at the interface with the background liver

Larger lesions can show central areas where the neoplastic vessels are more dilated, resembling adult type cavernous hemangiomas (Fig. 13.5). The center of larger lesions can also show degenerative changes, with fibrosis, thrombosis, infarction, and calcifications. These secondary changes are particularly common in larger, single tumors, many of which were previously classified as vascular malformations.

Fig. 13.5

Infantile hepatic hemangioma. The center of this tumor showed larger caliber vessels that resemble cavernous hemangioma

Infantile hemangiomas that have areas of solid growth (Fig. 13.6), papillary tufts (Fig. 13.7), Kaposiform-like areas, or significant cytological atypia are now considered to have foci of malignant transformation. Historically, tumors with these types of foci were classified as “type 2” infantile hemangioendothelioma. Overall, however, the clinical outcome in most infantile hemangiomas is similar, regardless of the presence or absence of atypia, or even small foci of malignant transformation, but almost all tumors that have aggressive behavior also have histologically atypical areas. Thus, it is important to section resection specimens adequately.

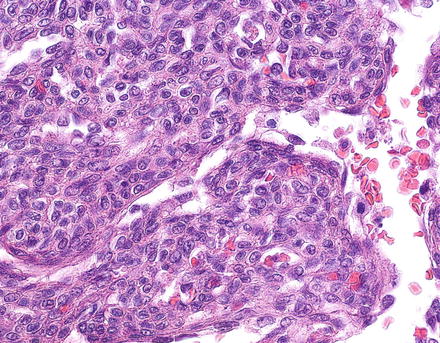

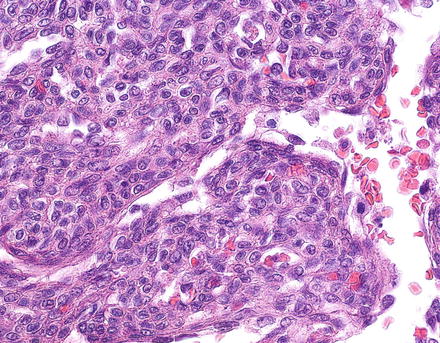

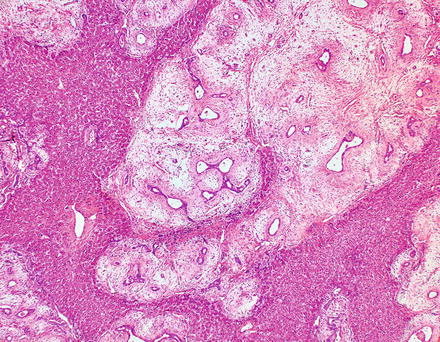

Fig. 13.6

Infantile hemangioma, focal malignant transformation. An area of solid growth and cytologic atypia is seen

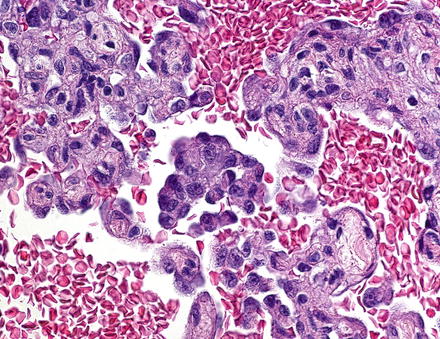

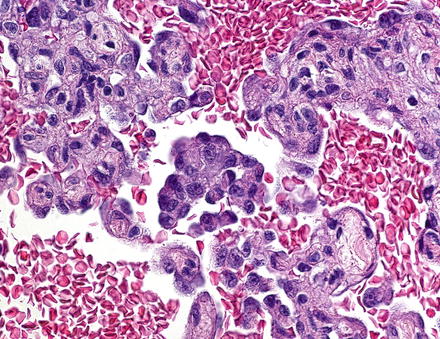

Fig. 13.7

Infantile hemangioma, focal malignant transformation. An area with cytologic atypia and papillary growth is seen

13.1.6 Immunohistochemical Features

Infantile hemangiomas stain with vascular markers such as CD31 and CD34. Focal infantile hemangiomas are GLUT1 negative, while multifocal and diffuse infantile hemangiomas are typically GLUT 1 positive.

13.2 Mesenchymal Hamartoma

13.2.1 Definition

Mesenchymal hamartoma is a benign tumor composed of loose mesenchymal tissue containing variably sized cysts, along with occasional benign bile ducts and small islands or cords of hepatocytes.

13.2.2 Clinical Features

Mesenchymal hamartomas have a slight male predominance and 85 % of cases present before the age of 3 years [4]. Rare mesenchymal hamartomas, however, have also been reported in adults [5]. The tumors usually present with painless, progressive abdominal distension. Occasionally, infants may be symptomatic and present with respiratory distress or congestive heart failure. In rare cases, tumors may also be detected in utero by prenatal ultrasound. Serum alpha-fetoprotein can be elevated in up to 40 % of cases [6], which can lead to misdiagnosis of hepatoblastoma in some cases [7].

The etiology of mesenchymal hamartoma is uncertain. It was thought to be a developmental abnormality; however, cytogenetic analyses have shown somatic chromosomal translocations involving chromosome 19, indicating that mesenchymal hamartoma is neoplastic. Other molecular studies suggest that at least a subset of cases have somatic mutations, indicating they are not solely caused by germline DNA defects. Multiple case reports have also reported an association between mesenchymal hamartoma and placental mesenchymal dysplasia [8–10], a hydropic change in the placental villi that resembles the findings in a partial mole but has no chromosomal abnormalities.

13.2.3 Gross Findings

Mesenchymal hamartomas are generally single tumors, but about 10 % are multifocal. In the multifocal cases, there tends to be a dominant lesion with smaller satellite lesions [11, 12]. Most (75 %) arise in the right lobe [4]. A subset of about 20 % of tumors are pedunculated lesions, hanging from the inferior surface of the liver [4]. On gross examination, they are well-demarcated, nonencapsulated masses composed of solid and cystic spaces. The relative amount of cystic versus solid areas varies considerably between different tumors, with some being predominately solid, and others largely cystic, including cases in which the cysts reach up to 30 cm in diameter. The cystic spaces contain clear or gelatinous fluid and lack communication with the bile ducts. Foci of necrosis or hemorrhage are generally not present. If present, those areas should be well sampled to rule out malignant transformation. In fact, any area that is grossly distinct from the rest of the tumor should be well sampled.

13.2.4 Microscopic Findings

Mesenchymal hamartomas are composed of a variety of tissue types. In most cases, most of the tumor is composed of loose mesenchyme containing variably sized cysts (Fig. 13.8). The mesenchymal tissue is typically paucicellular, containing scattered stellate shaped, bland cells, embedded in an edematous, myxoid, or densely collagenized matrix (Fig. 13.9). Mesenchymal hamartomas in adults tend to have less myxoid change and more striking stromal hyalinization than those in infants and children [5]. The cystic areas in mesenchymal hamartomas generally lack an epithelial lining and appear to represent degenerative cystic change of the mesenchymal tissue. Occasional small cysts may arise from biliary structures (Fig. 13.10), and rare reports have described cysts lined by mucous producing or intestinalized epithelium [13].

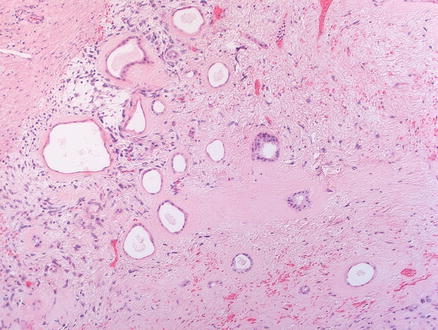

Fig. 13.8

Mesenchymal hamartoma. The section shows loose, paucicellular mesenchyme, with cyst-like areas

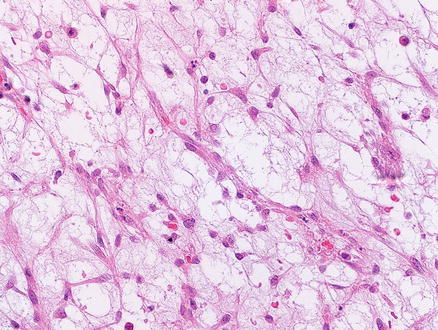

Fig. 13.9

Mesenchymal hamartoma. The cells within the mesenchyme are cytologically bland

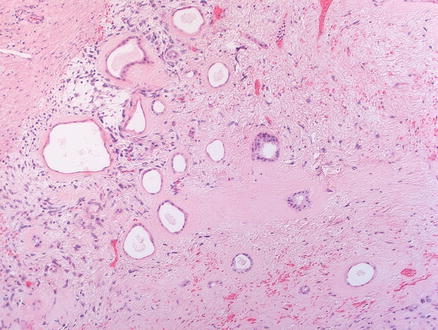

Fig. 13.10

Mesenchymal hamartoma. The bile duct-like structures are dilated and form small cysts. The background stroma is more hyalinized in this area

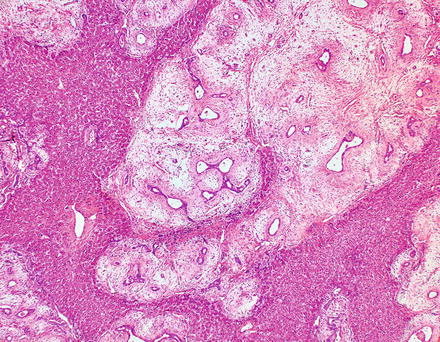

Mesenchymal hamartomas also contain scattered clusters of hepatocytes arranged in small islands or cords (Fig. 13.11), bile ducts, and clusters of blood vessels. In some cases, the hepatocytes and admixed portal-like areas will show a distinctive puzzle piece-like appearance (Fig. 13.12). The biliary structures may show a ductal plate malformation pattern or may be dilated to form small cysts. Foci of extramedullary hematopoiesis are commonly found in pediatric tumors but are less common in adult tumors [5]. Inflammation is generally mild and focal or absent.

Fig. 13.11

Mesenchymal hamartoma. An island of hepatocytes and some bile ducts are seen

Fig. 13.12

Mesenchymal hamartoma. At low power, a distinctive puzzle piece-like appearance is seen

In some mesenchymal hamartomas, the vessels can be somewhat more prominent, and in rare cases, tumors are composed of elements of both mesenchymal hamartoma and infantile hemangioma [14, 15]. An additional rare variant has been reported, which showed prominent myoid differentiation within the mesenchymal hamartoma [13].

13.2.5 Immunohistochemical Features

The cells in the loose connective tissue are typically vimentin positive and can also be smooth muscle actin and desmin positive [16, 17]. The entrapped hepatocytes may be glypican-3 positive [18], and in cases with elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein, the hepatic islands and bile ducts within the hamartoma can be positive for alpha-fetoprotein immunostain. The ductular epithelium is CK7 and CK19 positive.

13.2.6 Natural History/Prognosis

Mesenchymal hamartomas are benign lesions. However, rare cases may undergo malignant transformation to embryonal sarcoma. The treatment is surgical resection of the lesion and the overall survival rate is approximately 90 %.

13.3 Macroregenerative Nodule

13.3.1 Definition

Macroregenerative nodules are described in more detail in Chap. 4 but will be discussed briefly here. A macroregenerative nodule is a benign hepatocellular nodule whose size makes it stand out grossly from the background liver.

13.3.2 Clinical Features

Almost all macroregenerative nodules occur in cirrhotic livers. However, macroregenerative nodules can rarely be seen in noncirrhotic livers following extensive liver parenchymal loss. The most common setting for macroregenerative nodules in noncirrhotic livers is fulminant hepatitis in teen-aged individuals, who survive the initial injury and develop large regenerative nodules in the background of large areas of panacinar collapse. The regenerative nodules in this setting can be mistaken for malignancy on imaging studies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree