Chapter 1 Assessment of liver function and diagnostic studies

1 Reflecting the liver’s diverse functions, the colloquial term liver function tests (LFTs) includes true tests of hepatic synthetic function (e.g., serum albumin), tests of excretory function (e.g., serum bilirubin), and tests that reflect hepatic necroinflammatory activity (e.g., serum aminotransferases) or cholestasis (e.g., alkaline phosphatase).

2 Abnormal liver biochemistry test results are often the first clues to liver disease. The widespread inclusion of these tests in routine blood chemistry panels uncovers many patients with unrecognized hepatic dysfunction.

3 Normal or minimally abnormal liver biochemical test levels do not preclude significant liver disease, even cirrhosis.

4 Laboratory testing can assess the severity of liver disease and its prognosis; sequential testing may allow assessment of the effectiveness of therapy.

5 Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing the severity of liver disease, as well as for confirming the diagnosis for some causes. Newer diagnostic noninvasive modalities including serum markers of fibrosis and transient elastography may complement the use of liver biopsy.

Routine Liver Biochemical Tests

Serum bilirubin

2. Metabolism

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of hemoglobin and, to a lesser extent, heme-containing enzymes; 95% of bilirubin is derived from senescent red blood cells.

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of hemoglobin and, to a lesser extent, heme-containing enzymes; 95% of bilirubin is derived from senescent red blood cells.

Following red blood cell breakdown in the reticuloendothelial system, heme is degraded by the enzyme heme oxygenase in the endoplasmic reticulum.

Following red blood cell breakdown in the reticuloendothelial system, heme is degraded by the enzyme heme oxygenase in the endoplasmic reticulum.

Bilirubin is released into blood and tightly bound to albumin; free or unconjugated bilirubin is lipid soluble, is not filtered by the glomerulus, and does not appear in urine.

Bilirubin is released into blood and tightly bound to albumin; free or unconjugated bilirubin is lipid soluble, is not filtered by the glomerulus, and does not appear in urine.

Unconjugated bilirubin is taken up by the liver by a carrier-mediated process, attaches to intracellular storage proteins (ligands), and is conjugated by the enzyme uridine diphosphate (UDP)–glucuronyl transferase to form a diglucuronide and, to a lesser extent, a monoglucuronide.

Unconjugated bilirubin is taken up by the liver by a carrier-mediated process, attaches to intracellular storage proteins (ligands), and is conjugated by the enzyme uridine diphosphate (UDP)–glucuronyl transferase to form a diglucuronide and, to a lesser extent, a monoglucuronide.

When serum bilirubin glucuronides are elevated, some binding to albumin occurs (delta bilirubin), leading to absence of bilirubinuria despite conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; this phenomenon explains delayed resolution of jaundice during recovery from acute liver disease until catabolism of albumin-bound bilirubin occurs.

When serum bilirubin glucuronides are elevated, some binding to albumin occurs (delta bilirubin), leading to absence of bilirubinuria despite conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; this phenomenon explains delayed resolution of jaundice during recovery from acute liver disease until catabolism of albumin-bound bilirubin occurs.

Bilirubin in bile enters the small intestine; in the distal ileum and colon, bilirubin is hydrolyzed by beta-glucuronidases to form unconjugated bilirubin, which is then reduced by gut bacteria to colorless urobilinogens; a small amount of urobilinogen is reabsorbed by the enterohepatic circulation and mostly excreted in the bile, with a smaller proportion undergoing urinary excretion.

Bilirubin in bile enters the small intestine; in the distal ileum and colon, bilirubin is hydrolyzed by beta-glucuronidases to form unconjugated bilirubin, which is then reduced by gut bacteria to colorless urobilinogens; a small amount of urobilinogen is reabsorbed by the enterohepatic circulation and mostly excreted in the bile, with a smaller proportion undergoing urinary excretion.

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of hemoglobin and, to a lesser extent, heme-containing enzymes; 95% of bilirubin is derived from senescent red blood cells.

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of hemoglobin and, to a lesser extent, heme-containing enzymes; 95% of bilirubin is derived from senescent red blood cells. Following red blood cell breakdown in the reticuloendothelial system, heme is degraded by the enzyme heme oxygenase in the endoplasmic reticulum.

Following red blood cell breakdown in the reticuloendothelial system, heme is degraded by the enzyme heme oxygenase in the endoplasmic reticulum. Bilirubin is released into blood and tightly bound to albumin; free or unconjugated bilirubin is lipid soluble, is not filtered by the glomerulus, and does not appear in urine.

Bilirubin is released into blood and tightly bound to albumin; free or unconjugated bilirubin is lipid soluble, is not filtered by the glomerulus, and does not appear in urine. Unconjugated bilirubin is taken up by the liver by a carrier-mediated process, attaches to intracellular storage proteins (ligands), and is conjugated by the enzyme uridine diphosphate (UDP)–glucuronyl transferase to form a diglucuronide and, to a lesser extent, a monoglucuronide.

Unconjugated bilirubin is taken up by the liver by a carrier-mediated process, attaches to intracellular storage proteins (ligands), and is conjugated by the enzyme uridine diphosphate (UDP)–glucuronyl transferase to form a diglucuronide and, to a lesser extent, a monoglucuronide. When serum bilirubin glucuronides are elevated, some binding to albumin occurs (delta bilirubin), leading to absence of bilirubinuria despite conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; this phenomenon explains delayed resolution of jaundice during recovery from acute liver disease until catabolism of albumin-bound bilirubin occurs.

When serum bilirubin glucuronides are elevated, some binding to albumin occurs (delta bilirubin), leading to absence of bilirubinuria despite conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; this phenomenon explains delayed resolution of jaundice during recovery from acute liver disease until catabolism of albumin-bound bilirubin occurs. Bilirubin in bile enters the small intestine; in the distal ileum and colon, bilirubin is hydrolyzed by beta-glucuronidases to form unconjugated bilirubin, which is then reduced by gut bacteria to colorless urobilinogens; a small amount of urobilinogen is reabsorbed by the enterohepatic circulation and mostly excreted in the bile, with a smaller proportion undergoing urinary excretion.

Bilirubin in bile enters the small intestine; in the distal ileum and colon, bilirubin is hydrolyzed by beta-glucuronidases to form unconjugated bilirubin, which is then reduced by gut bacteria to colorless urobilinogens; a small amount of urobilinogen is reabsorbed by the enterohepatic circulation and mostly excreted in the bile, with a smaller proportion undergoing urinary excretion.3. Measurement of serum bilirubin

a. van den Bergh reaction

Total serum bilirubin represents all bilirubin that reacts within 30 minutes in the presence of alcohol (an accelerating agent).

Total serum bilirubin represents all bilirubin that reacts within 30 minutes in the presence of alcohol (an accelerating agent).

Direct serum bilirubin is the fraction that reacts with the diazo reagent in an aqueous medium within 1 minute and corresponds to conjugated bilirubin.

Direct serum bilirubin is the fraction that reacts with the diazo reagent in an aqueous medium within 1 minute and corresponds to conjugated bilirubin.

Total serum bilirubin represents all bilirubin that reacts within 30 minutes in the presence of alcohol (an accelerating agent).

Total serum bilirubin represents all bilirubin that reacts within 30 minutes in the presence of alcohol (an accelerating agent). Direct serum bilirubin is the fraction that reacts with the diazo reagent in an aqueous medium within 1 minute and corresponds to conjugated bilirubin.

Direct serum bilirubin is the fraction that reacts with the diazo reagent in an aqueous medium within 1 minute and corresponds to conjugated bilirubin.4. Classification of hyperbilirubinemia

a. Unconjugated (bilirubin nearly always less than 7 mg/dL)

Overproduction (presentation to liver of bilirubin load that exceeds hepatic capacity for uptake and conjugation): hemolysis, ineffective erythropoiesis, resorption of hematoma

Overproduction (presentation to liver of bilirubin load that exceeds hepatic capacity for uptake and conjugation): hemolysis, ineffective erythropoiesis, resorption of hematoma

Overproduction (presentation to liver of bilirubin load that exceeds hepatic capacity for uptake and conjugation): hemolysis, ineffective erythropoiesis, resorption of hematoma

Overproduction (presentation to liver of bilirubin load that exceeds hepatic capacity for uptake and conjugation): hemolysis, ineffective erythropoiesis, resorption of hematoma5. Urine bilirubin and urobilinogen

Urinary urobilinogen (rarely measured now) is found in patients with hemolysis (increased production of bilirubin), gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or hepatocellular disease (impaired removal of urobilinogen from blood).

Urinary urobilinogen (rarely measured now) is found in patients with hemolysis (increased production of bilirubin), gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or hepatocellular disease (impaired removal of urobilinogen from blood).

Absence of urobilinogen from urine suggests interruption of enterohepatic circulation of bile pigments, as in complete bile duct obstruction.

Absence of urobilinogen from urine suggests interruption of enterohepatic circulation of bile pigments, as in complete bile duct obstruction.

Urinary urobilinogen (rarely measured now) is found in patients with hemolysis (increased production of bilirubin), gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or hepatocellular disease (impaired removal of urobilinogen from blood).

Urinary urobilinogen (rarely measured now) is found in patients with hemolysis (increased production of bilirubin), gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or hepatocellular disease (impaired removal of urobilinogen from blood). Absence of urobilinogen from urine suggests interruption of enterohepatic circulation of bile pigments, as in complete bile duct obstruction.

Absence of urobilinogen from urine suggests interruption of enterohepatic circulation of bile pigments, as in complete bile duct obstruction.Serum aminotransferases (Table 1.1)

1. These intracellular enzymes are released from injured hepatocytes and are the most useful marker of hepatic injury (inflammation or cell necrosis).

2. Clinical usefulness

Levels increase with body mass index and may correlate with the risk of coronary artery disease and mortality.

Levels increase with body mass index and may correlate with the risk of coronary artery disease and mortality.

Levels may rise acutely with a high caloric meal or ingestion of acetaminophen 4 g/day; coffee appears to lower levels.

Levels may rise acutely with a high caloric meal or ingestion of acetaminophen 4 g/day; coffee appears to lower levels.

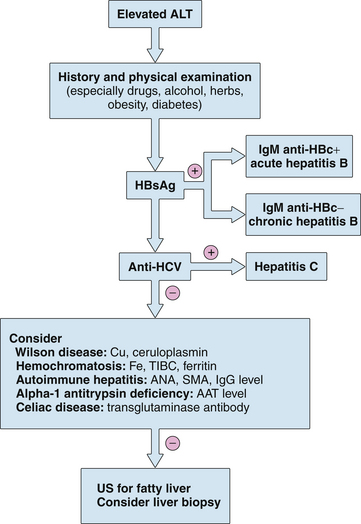

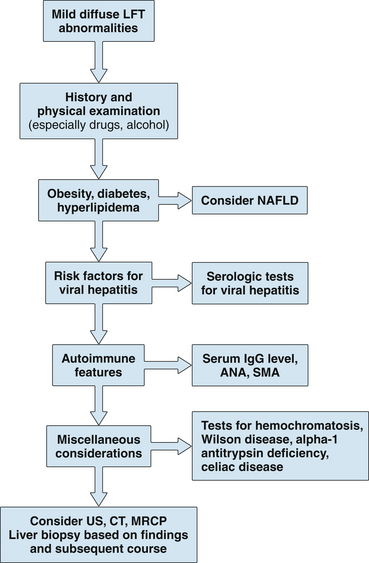

Aminotransferase elevations are often the first biochemical abnormalities detected in patients with viral, autoimmune, or drug-induced hepatitis; the degree of elevation may correlate with the extent of hepatic injury but is generally not of prognostic significance.

Aminotransferase elevations are often the first biochemical abnormalities detected in patients with viral, autoimmune, or drug-induced hepatitis; the degree of elevation may correlate with the extent of hepatic injury but is generally not of prognostic significance.

In alcoholic hepatitis, the serum AST is usually no more than 2 to 10 times the upper limit of normal, and the ALT is normal or nearly normal with an AST:ALT ratio greater than 2; relatively low ALT levels may result from a deficiency of pyridoxal 5-phosphate, a necessary cofactor for hepatic synthesis of ALT. In contrast, in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, ALT is typically higher than AST until cirrhosis develops.

In alcoholic hepatitis, the serum AST is usually no more than 2 to 10 times the upper limit of normal, and the ALT is normal or nearly normal with an AST:ALT ratio greater than 2; relatively low ALT levels may result from a deficiency of pyridoxal 5-phosphate, a necessary cofactor for hepatic synthesis of ALT. In contrast, in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, ALT is typically higher than AST until cirrhosis develops.

Aminotransferase levels may be higher than 3000 U/L in acute or chronic viral hepatitis or drug-induced liver injury; in acute liver failure or ischemic hepatitis (shock liver), even higher values (higher than 5000 U/L) may be found.

Aminotransferase levels may be higher than 3000 U/L in acute or chronic viral hepatitis or drug-induced liver injury; in acute liver failure or ischemic hepatitis (shock liver), even higher values (higher than 5000 U/L) may be found.

Mild to moderate elevations of aminotransferase levels are typical of chronic viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, and celiac disease.

Mild to moderate elevations of aminotransferase levels are typical of chronic viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, and celiac disease.

Levels increase with body mass index and may correlate with the risk of coronary artery disease and mortality.

Levels increase with body mass index and may correlate with the risk of coronary artery disease and mortality. Levels may rise acutely with a high caloric meal or ingestion of acetaminophen 4 g/day; coffee appears to lower levels.

Levels may rise acutely with a high caloric meal or ingestion of acetaminophen 4 g/day; coffee appears to lower levels. Aminotransferase elevations are often the first biochemical abnormalities detected in patients with viral, autoimmune, or drug-induced hepatitis; the degree of elevation may correlate with the extent of hepatic injury but is generally not of prognostic significance.

Aminotransferase elevations are often the first biochemical abnormalities detected in patients with viral, autoimmune, or drug-induced hepatitis; the degree of elevation may correlate with the extent of hepatic injury but is generally not of prognostic significance. In alcoholic hepatitis, the serum AST is usually no more than 2 to 10 times the upper limit of normal, and the ALT is normal or nearly normal with an AST:ALT ratio greater than 2; relatively low ALT levels may result from a deficiency of pyridoxal 5-phosphate, a necessary cofactor for hepatic synthesis of ALT. In contrast, in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, ALT is typically higher than AST until cirrhosis develops.

In alcoholic hepatitis, the serum AST is usually no more than 2 to 10 times the upper limit of normal, and the ALT is normal or nearly normal with an AST:ALT ratio greater than 2; relatively low ALT levels may result from a deficiency of pyridoxal 5-phosphate, a necessary cofactor for hepatic synthesis of ALT. In contrast, in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, ALT is typically higher than AST until cirrhosis develops. Aminotransferase levels may be higher than 3000 U/L in acute or chronic viral hepatitis or drug-induced liver injury; in acute liver failure or ischemic hepatitis (shock liver), even higher values (higher than 5000 U/L) may be found.

Aminotransferase levels may be higher than 3000 U/L in acute or chronic viral hepatitis or drug-induced liver injury; in acute liver failure or ischemic hepatitis (shock liver), even higher values (higher than 5000 U/L) may be found. Mild to moderate elevations of aminotransferase levels are typical of chronic viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, and celiac disease.

Mild to moderate elevations of aminotransferase levels are typical of chronic viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, and celiac disease.5. Abnormally low aminotransferase levels have been associated with uremia and chronic hemodialysis; chronic viral hepatitis in this population may not result in aminotransferase elevation.

TABLE 1.1 Causes of elevated serum aminotransferase levels∗

| Mild elevation (<5× normal) | Marked elevation (>15× normal) |

|---|---|

| Hepatic: ALT predominant | Acute viral hepatitis (A–E, herpes) |

| Chronic viral hepatitis | DILI |

| Acute viral hepatitis (A–E, EBV, CMV) | Ischemic hepatitis |

| NAFLD | Autoimmune hepatitis |

| Hemochromatosis | Wilson disease |

| DILI | Acute bile duct obstruction |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Acute Budd–Chiari syndrome |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | Hepatic artery ligation |

| Wilson disease | |

| Celiac disease | |

| Hepatic: AST predominant | |

| Alcohol-related liver injury (AST:ALT >2:1) | |

| Cirrhosis | |

| Nonhepatic | |

| Strenuous exercise | |

| Hemolysis | |

| Myopathy | |

| Thyroid disease | |

| Macro-AST |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CMV, cytomegalovirus; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

∗ Almost any liver disease may be associated with ALT levels 5 times to 15 times normal.

Serum alkaline phosphatase

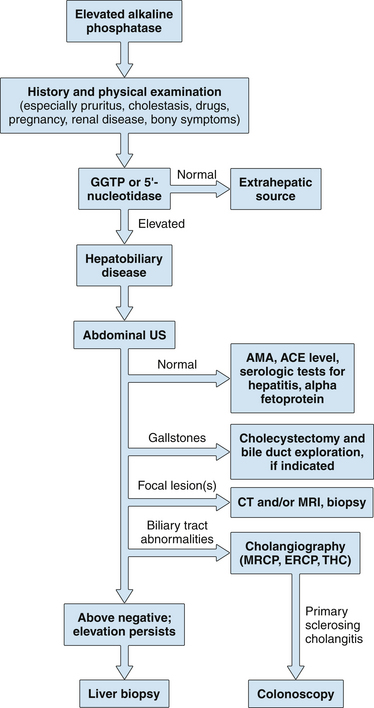

1. Hepatic alkaline phosphatase is one of several alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes found in humans and is bound to hepatic canalicular membrane; various laboratory methods are available for its measurement, and thus comparison of results obtained by different techniques may be misleading.

2. This test is sensitive for detection of biliary tract obstruction (a normal value is highly unusual in significant biliary obstruction); interference with bile flow may be intrahepatic or extrahepatic.

An increase in serum alkaline phosphatase results from increased hepatic synthesis of the enzyme, rather than leakage from bile duct cells or failure to clear circulating alkaline phosphatase; because it is synthesized in response to biliary obstruction, the alkaline phosphatase level may be normal early in the course of acute suppurative cholangitis when the serum aminotransferases are already elevated.

An increase in serum alkaline phosphatase results from increased hepatic synthesis of the enzyme, rather than leakage from bile duct cells or failure to clear circulating alkaline phosphatase; because it is synthesized in response to biliary obstruction, the alkaline phosphatase level may be normal early in the course of acute suppurative cholangitis when the serum aminotransferases are already elevated.

An increase in serum alkaline phosphatase results from increased hepatic synthesis of the enzyme, rather than leakage from bile duct cells or failure to clear circulating alkaline phosphatase; because it is synthesized in response to biliary obstruction, the alkaline phosphatase level may be normal early in the course of acute suppurative cholangitis when the serum aminotransferases are already elevated.

An increase in serum alkaline phosphatase results from increased hepatic synthesis of the enzyme, rather than leakage from bile duct cells or failure to clear circulating alkaline phosphatase; because it is synthesized in response to biliary obstruction, the alkaline phosphatase level may be normal early in the course of acute suppurative cholangitis when the serum aminotransferases are already elevated.3. Isolated elevation of alkaline phosphatase

High levels are associated with biliary obstruction, sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, sepsis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cholestatic drug reactions, and other causes of vanishing bile duct syndrome; in critically ill patients, high levels may indicate secondary sclerosing cholangitis with rapid progression to cirrhosis.

High levels are associated with biliary obstruction, sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, sepsis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cholestatic drug reactions, and other causes of vanishing bile duct syndrome; in critically ill patients, high levels may indicate secondary sclerosing cholangitis with rapid progression to cirrhosis.

Nonhepatic sources of alkaline phosphatase are bone, intestine, kidney, and placenta (different isoenzymes); striking elevations are seen in Paget’s disease of the bone, osteoblastic bone metastases, small bowel obstruction, and normal pregnancy.

Nonhepatic sources of alkaline phosphatase are bone, intestine, kidney, and placenta (different isoenzymes); striking elevations are seen in Paget’s disease of the bone, osteoblastic bone metastases, small bowel obstruction, and normal pregnancy.

Hepatic origin of an elevated alkaline phosphatase level is suggested by simultaneous elevation of either serum gamma glutamyltranspeptidase (GGTP) or 5’-nucleotidase (5NT).

Hepatic origin of an elevated alkaline phosphatase level is suggested by simultaneous elevation of either serum gamma glutamyltranspeptidase (GGTP) or 5’-nucleotidase (5NT).

Hepatic alkaline phosphatase is more heat stable than bony alkaline phosphatase. The degree of overlap makes this test less useful than GGTP or 5NT.

Hepatic alkaline phosphatase is more heat stable than bony alkaline phosphatase. The degree of overlap makes this test less useful than GGTP or 5NT.

High levels are associated with biliary obstruction, sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, sepsis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cholestatic drug reactions, and other causes of vanishing bile duct syndrome; in critically ill patients, high levels may indicate secondary sclerosing cholangitis with rapid progression to cirrhosis.

High levels are associated with biliary obstruction, sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, sepsis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cholestatic drug reactions, and other causes of vanishing bile duct syndrome; in critically ill patients, high levels may indicate secondary sclerosing cholangitis with rapid progression to cirrhosis. Nonhepatic sources of alkaline phosphatase are bone, intestine, kidney, and placenta (different isoenzymes); striking elevations are seen in Paget’s disease of the bone, osteoblastic bone metastases, small bowel obstruction, and normal pregnancy.

Nonhepatic sources of alkaline phosphatase are bone, intestine, kidney, and placenta (different isoenzymes); striking elevations are seen in Paget’s disease of the bone, osteoblastic bone metastases, small bowel obstruction, and normal pregnancy. Hepatic origin of an elevated alkaline phosphatase level is suggested by simultaneous elevation of either serum gamma glutamyltranspeptidase (GGTP) or 5’-nucleotidase (5NT).

Hepatic origin of an elevated alkaline phosphatase level is suggested by simultaneous elevation of either serum gamma glutamyltranspeptidase (GGTP) or 5’-nucleotidase (5NT). Hepatic alkaline phosphatase is more heat stable than bony alkaline phosphatase. The degree of overlap makes this test less useful than GGTP or 5NT.

Hepatic alkaline phosphatase is more heat stable than bony alkaline phosphatase. The degree of overlap makes this test less useful than GGTP or 5NT.5. Low serum levels of alkaline phosphatase may occur in hypothyroidism, pernicious anemia, zinc deficiency, congenital hypophosphatasia, and fulminant Wilson disease.