Chapter 11 Ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

1 In the United States, 85% of cases of ascites occur in the setting of cirrhosis with portal hypertension; the development of ascites is associated with a 50% 2-year survival.

2 Evaluation of the patient with ascites begins with a thorough history and physical examination focused on identifying clinical clues to the underlying disease process.

3 Abdominal paracentesis with ascitic fluid analysis is a safe and cost-effective strategy in the differential diagnosis of ascites. Routine ascitic fluid tests include cell count, culture in blood culture bottles, albumin, and total protein, with additional testing depending on the clinical setting.

4 Treatment of patients with cirrhosis and ascites involves a stepwise approach including dietary sodium restriction and dual diuretic therapy. Second-line therapies include intermittent large-volume paracentesis (LVP), transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and liver transplantation.

5 Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is the prototype ascitic fluid infection and usually develops in the setting of preexisting ascites in patients with cirrhosis. The morbidity and mortality of ascitic fluid infection and the efficacy of early treatment warrant a high index of suspicion, early diagnosis by paracentesis with appropriate ascitic fluid analysis, and prompt non-nephrotoxic antibiotic treatment.

Overview of Ascites

Epidemiology and Natural History

1. In the United States, 85% of cases of ascites occur in the setting of cirrhosis. Table 11.1 lists common causes of ascites.

TABLE 11.1 Causes of ascites in the United States

| Cause | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 85 |

| Miscellaneous portal hypertension-related | 8 |

| Cardiac ascites | 3 |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | 2 |

| Miscellaneous non–portal hypertension-related | 2 |

Pathogenesis in the Setting of Cirrhosis

1. Portal hypertension leads to excess formation of fluid within the congested hepatic sinusoids; the fluid overwhelms intrahepatic lymphatics and weeps across the liver.

2. The overflow theory proposes that a stimulus arising from the liver results in a primary increase in plasma volume through increased renal sodium retention.

3. The underfill theory proposes that when ascites formation begins, the intravascular fluid compartment contracts, with an increase in the plasma oncotic pressure and a decrease in portal venous pressure; this results in a secondary increase in renal sodium retention in an attempt to compensate.

4. The peripheral arterial vasodilatation theory is a modification of the underfill theory and proposes that peripheral arterial vasodilatation results in an increase in vascular capacitance and a decrease in effective plasma volume, which results in the secondary increase in renal sodium retention.

Evaluation of the Patient with Ascites

History

2. A thorough history is necessary to rule out a cause other than liver disease, such as heart failure, tuberculosis, or nephrotic syndrome (Table 11.2).

3. History related to ascites

The most common symptom of ascites is an increase in abdominal girth accompanied by weight gain, frequently with lower extremity edema.

The most common symptom of ascites is an increase in abdominal girth accompanied by weight gain, frequently with lower extremity edema.

Ascites associated with fever and/or abdominal pain may indicate ascitic fluid infection or malignancy.

Ascites associated with fever and/or abdominal pain may indicate ascitic fluid infection or malignancy.

The most common symptom of ascites is an increase in abdominal girth accompanied by weight gain, frequently with lower extremity edema.

The most common symptom of ascites is an increase in abdominal girth accompanied by weight gain, frequently with lower extremity edema. Ascites associated with fever and/or abdominal pain may indicate ascitic fluid infection or malignancy.

Ascites associated with fever and/or abdominal pain may indicate ascitic fluid infection or malignancy.TABLE 11.2 Clinical clues to causes of ascites other than cirrhosis

| Cause | Clinical clues |

|---|---|

| Cardiac ascites | Setting and examination findings suggestive of heart failure |

| Malignant ascites | Setting of known malignancy and absence of stigmata of liver disease; often abdominal pain and profound weight loss |

| Tuberculous ascites | Persistent abdominal pain and fever; often extraperitoneal tuberculosis |

| Nephrotic syndrome | Anasarca and substantial proteinuria in a diabetic patient |

| Pancreatic ascites | Follows episode of severe acute pancreatitis or occurs in the setting of chronic pancreatitis |

Physical Examination

1. Physical signs suggestive of cirrhosis and portal hypertension (e.g., spider telangiectases, palmar erythema, abdominal wall collateral vessels, splenomegaly, or asterixis)

Abdominal Ultrasonography

2. Confirmation or refutation of the presence of portal hypertension (e.g., spleen greater than 12 cm maximum dimension and enlarged portal vein)

Ascitic Fluid Analysis

Diagnostic Paracentesis

2. Technically, diagnostic paracentesis involves passing a steel 22-gauge needle, by a Z-tract technique, below the level of percussed dullness, either in the left lower quadrant (two fingerbreadths cephalic and two fingerbreadths medial to the anterior superior iliac spine) or in the midline between the symphysis pubis and umbilicus.

3. Complications include fluid leak at the site (if a Z-tract is not used), abdominal wall hematoma, and inadvertent bowel perforation.

Ascitic Fluid Tests

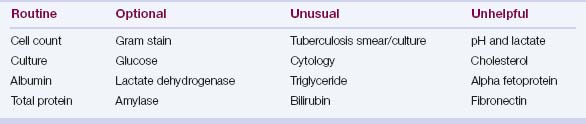

Ascitic fluid tests commonly ordered are shown in Table 11.3.

1. Ascitic fluid cell count is the most important test.

Fluid with 250 or more polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs)/mm3 (and a predominance of PMNs) is presumed infected.

Fluid with 250 or more polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs)/mm3 (and a predominance of PMNs) is presumed infected.

Fluid with 250 or more polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs)/mm3 (and a predominance of PMNs) is presumed infected.

Fluid with 250 or more polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs)/mm3 (and a predominance of PMNs) is presumed infected.2. Culture results are optimized by immediate inoculation of aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles with 10 mL of ascitic fluid at the bedside (sensitivity is approximately 90%).

3. Ascitic fluid albumin measurement is necessary to calculate the serum–ascites albumin gradient (SAAG).

4. Ascitic fluid total protein measurement assists in determining the cause of ascites (Table 11.5) and the risk of ascitic fluid infection (values lower than 1.0 g/dL indicate a high risk).

TABLE 11.4 Differential diagnosis of ascites based on the serum–ascites albumin gradient

| High gradient (≥1.1 g/dL) | Low gradient (<1.1 g/dL) |

|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | Peritoneal carcinomatosis |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | Tuberculous peritonitis |

| Cardiac ascites | Pancreatic ascites |

| Massive liver metastases | Biliary ascites |

| Fulminant hepatic failure | Nephrotic syndrome |

| Budd–Chiari syndrome | Connective tissue diseases |

| Portal vein thrombosis | Intestinal obstruction/infarction |

| Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome | Postoperative lymphatic leak |

| Acute fatty liver of pregnancy | |

| Myxedema | |

| “Mixed” ascites |

TABLE 11.5 Ascitic fluid clues regarding the cause of ascites

| Cause of ascites | Ascitic fluid clues |

|---|---|

| Cirrhotic ascites | SAAG ≥1.1 g/dL AFTP <2.5 g/dL (usually) |

| Cardiac ascites | SAAG ≥1.1 g/dL AFTP ≥2.5 g/dL |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | SAAG <1.1 g/dLAFTP ≥2.5 g/dL Cytology generally yields malignant cells |

| Tuberculous ascites | SAAG <1.1 g/dL (without cirrhosis) AFTP >2.5 g/dL (without cirrhosis) WBC >500/mm3, lymphocyte predominance |

| Chylous ascites | SAAG <1.1 g/dL AFTP ≥2.5 g/dL Triglycerides in ascites > serum (usually >200 mg/dL) |

| Nephrotic syndrome | SAAG <1.1 g/dL AFTP <2.5 g/dL |

| Pancreatic ascites | SAAG <1.1 g/dL AFTP ≥2.5 g/dL Amylase in ascites > amylase in serum (often >1000 U/L) |

AFTP, ascitic fluid total protein; SAAG, serum–ascites albumin gradient; WBC, white blood cell count.