Since its introduction in 1973, the artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) has become widely accepted therapy, particularly for male incontinence. In this article, the authors review their experience with more than 600 artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) devices and discuss practical points concerning surgery and revisions. Their routine surgical approach as a means of reporting on technical lessons learned is also described.

Since its introduction in 1973 (American Medical Systems [AMS] model 721), the artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) has become a widely accepted therapy, particularly for male urinary incontinence. Over the years, improvements in product design, surgical techniques, and patient selection have led to increased reliability with durable success. The current American Medical Systems model 800 (AMS 800) AUS was introduced in 1983 and has a 20-year history of use. This device has become the gold-standard treatment for incontinence of many causes, including prostatectomy, radiation therapy, neuropathy, and as a part of reconstructive procedures. Outcomes with the device are excellent, and most patients are pleased with the results, an outcome that persists in the long term. The authors review their experience with more than 600 AUS devices and discuss practical points concerning surgery and revisions. They describe their routine surgical approach as a means of reporting on technical lessons learned.

Preoperative evaluation

Evaluation of patients for treatment with an AUS starts with a comprehensive office visit, including taking a history and performing a physical examination, urinalysis, and urine culture. Each patient completes a 72-hour voiding diary and a 24-hour urinary pad weight test that is brought to the office visit. The pad-weight study is an invaluable objective measure of the magnitude of the incontinence. During the office visit, videourodynamics are performed. This step, along with the voiding diary and patient history, helps confirm the factors contributing to the incontinence and identifies factors that may mitigate against a good outcome. Some investigators have suggested that urodynamic study is superfluous to the selection of the patient for implantation, but the authors disagree. Cystoscopy is performed in all patients to evaluate the urethra for a healthy placement site and to exclude urethral strictures and anastomotic contracture.

Preparation

The authors attempt to ensure that the urine is sterile and that infected foci are not present the week before surgery. Preoperative antibiotics (an aminoglycoside and cephazolin or vancomycin) are given intravenously. Surgery is conducted under general or spinal anesthesia with the patient in the low lithotomy position and with the entire operative site shaved. Before draping, a 10-minute, iodine-based skin preparation is performed that includes the lower abdomen, genitals, and perineum. A 16-French Foley catheter is placed to drain the bladder and to facilitate identification and dissection of the urethra, which is the first step of the procedure.

Preparation

The authors attempt to ensure that the urine is sterile and that infected foci are not present the week before surgery. Preoperative antibiotics (an aminoglycoside and cephazolin or vancomycin) are given intravenously. Surgery is conducted under general or spinal anesthesia with the patient in the low lithotomy position and with the entire operative site shaved. Before draping, a 10-minute, iodine-based skin preparation is performed that includes the lower abdomen, genitals, and perineum. A 16-French Foley catheter is placed to drain the bladder and to facilitate identification and dissection of the urethra, which is the first step of the procedure.

Cuff placement

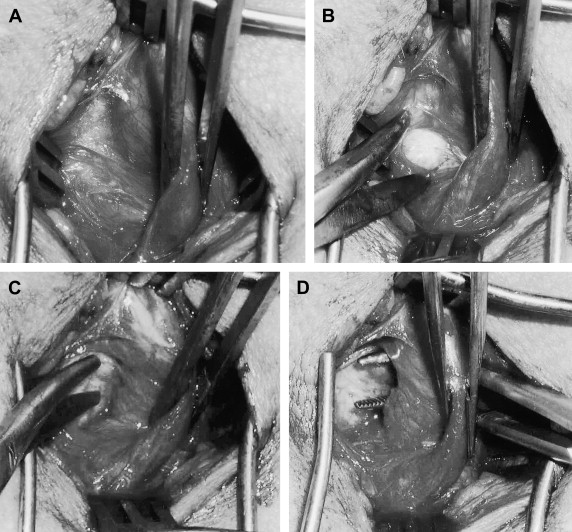

The ideal site for placement of the AUS cuff is at the bulbar urethra just proximal to the bifurcation of the corporal bodies ( Fig. 1 ). Bucks fascia is incised, as it reflects off the bulbar urethra onto the diverging corporal bodies. A tunnel can be made using scissor dissection, dorsal to Buck’s fascia over the roof of the urethra as it passes between the separating corporal bodies. A right-angle clamp may be passed atraumatically through this tunnel while avoiding the dorsal aspect of the urethra ( Fig. 2 ). Blunt or spread dissection can be hazardous in this area, as it risks the thinning of the urethra or splitting into the urethra. Being posterior to the bifurcation of the corporal bodies is important in that it allows for a safer dissection dorsal to the urethra and presents a larger urethra.

Generally, a 4.0- or 4.5-cm AUS cuff is selected, and a cuff that has the snuggest fit, but is not obstructive, results in better continence ( Fig. 3 ). The circumference of the urethra at the dissected site is measured in centimeters to guide selection of cuff size. The authors believe that the measurement should be taken on a bare corpus spongiosum, as intervening fat or muscle rapidly atrophies, causing leakage of the device. Other than when implanting a transcorporal cuff, the cuff size is always smaller than the measured circumference of the urethra, because much of what is measured around the urethra is compressible spongy tissue and because postoperative subcuff atrophy will occur. Although no accurate guide can be given, generally if the corpus spongiosum measures 5 cm, the authors implant a 4-cm cuff.

The best test of cuff fit is the visual and endoscopic appearance after it has been placed around the urethra. If the measurement was incorrect, it is often obvious (the cuff looks obviously too loose or is strangling the urethra). At this point, the cuff should be changed, regardless of waste of equipment. If the margin of tightness is small, cuff size can be increased by a few millimeters by excising up to 2 mm from inside the tab. Caution must be used in performing this unapproved maneuver, as removing too much from the cuff tab may create a hole that is large enough to cause herniation of the cuff through the tab hole and malfunction of the device. The authors routinely perform urethroscopy after urethral dissection and cuff placement to ensure an absence of dissection injury to the urethra and to confirm good cuff sizing.

The tubing to the AUS cuff is passed from the perineal dissection using a transfer trocar or a tonsil clamp (underneath Colles’ fascia and staying close to the pubic bone) to the right lower quadrant abdominal wound where the incision is located for placement of the reservoir and scrotal pump. Throughout the procedure, the operative site and the components periodically and liberally are irrigated with an antibiotic solution.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree