Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) and portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) are important causes of chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. These gastric mucosal lesions are mostly diagnosed on upper endoscopy and can be distinguished based on their appearance or location in the stomach. In some situations, especially in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension, a diffuse pattern and involvement of gastric mucosa are seen with both GAVE and severe PHG. The diagnosis in such cases is hard to determine on visual inspection, and thus, biopsy and histologic evaluation can be used to help differentiate GAVE from PHG.

Key points

- •

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) and portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) are 2 distinct causes of chronic gastrointestinal bleeding.

- •

In patients with cirrhosis, often these mucosal lesions can be relatively easy to distinguish on upper endoscopy based on their appearance: as “watermelon stomach” (red stripes pattern) in the case of GAVE, or “snake skin” (mosaic pattern) in the case of PHG, or location: gastric antrum for GAVE and fundus or upper body in PHG.

- •

Diffuse red spots or nodular pattern on gastric mucosa is occasionally encountered in cirrhotics, which is seen with both GAVE and severe PHG.

- •

When the diagnosis is unclear, biopsy and histologic evaluation (and use of GAVE score) help in differentiating GAVE from PHG.

Introduction

Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) are 2 important causes of gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB). Overall, both are gastric mucosal lesions that are uncommon causes of overt GIB but are frequently associated with chronic blood loss and iron deficiency anemia. GAVE and PHG are typically seen in distinct patient populations; however, both conditions are encountered in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension and can cause nonvariceal GIB. The clinical presentation and morphologic appearance of these lesions can be relatively similar, yet the management is clearly different. Thus, it is imperative to make an accurate diagnosis and differentiation between GAVE and PHG to formulate suitable treatment decisions.

In this article, the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and recent advancements in the management of both GAVE and PHG are briefly reviewed, with an emphasis on the treatment options in the presence of advanced liver disease.

Introduction

Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) are 2 important causes of gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB). Overall, both are gastric mucosal lesions that are uncommon causes of overt GIB but are frequently associated with chronic blood loss and iron deficiency anemia. GAVE and PHG are typically seen in distinct patient populations; however, both conditions are encountered in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension and can cause nonvariceal GIB. The clinical presentation and morphologic appearance of these lesions can be relatively similar, yet the management is clearly different. Thus, it is imperative to make an accurate diagnosis and differentiation between GAVE and PHG to formulate suitable treatment decisions.

In this article, the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and recent advancements in the management of both GAVE and PHG are briefly reviewed, with an emphasis on the treatment options in the presence of advanced liver disease.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of GAVE is unknown because of its relatively silent presentation and its association with a wide variety of systemic diseases. In addition, GAVE was not described reliably in the past, and it was not until 1995 that the distinction was made between GAVE and PHG in patients with cirrhosis. During the evaluation of chronic anemia, GAVE is typically found to be the cause in elderly women and is also is associated with several chronic systemic diseases (chronic renal failure, autoimmune diseases, systemic sclerosis, cardiac diseases, and bone marrow transplantation). On routine upper endoscopy, GAVE is seen in 3% and 2% of patients with advanced liver disease and those undergoing liver transplantation, respectively. GAVE is considered to be responsible for 4% of nonvariceal upper GIB in patients with and without portal hypertension.

Diagnosis

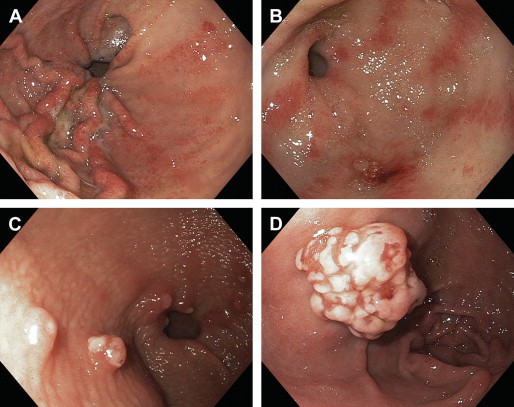

GAVE is described as a vascular lesion consisting of abnormally dilated and tortuous gastric mucosal capillaries (ectasia) with mural spindle cell proliferation (smooth muscle cells and myofibroblasts), focal thrombosis, and fibrohyalonosis. These histologic findings are incorporated into the “GAVE score” ( Table 1 ), which can be used to make a diagnosis of GAVE with high accuracy (70%–85%) on a gastric biopsy to differentiate it from PHG. Biopsy, however, is often not needed to diagnose GAVE because of its characteristic morphologic appearance. Conventionally, upper endoscopy has been used to diagnose GAVE based on the finding of reddish spots either organized in stripes radially projecting proximally from the pylorus (watermelon stomach) or arranged in a diffuse (honeycomb stomach) or nodular pattern (nodular antral gastropathy) ( Fig. 1 ). These lesions are seen in the form of erythematous and at times raised mucosa with visible underlying ectatic vessels, which are located mainly in the antrum of the stomach. In cirrhotics, a clear distinction from PHG, especially in a diffuse or nodular type pattern, is difficult to make on endoscopic inspection and a biopsy is often needed. Among other endoscopic modalities, capsule endoscopy has been recently used to evaluate GAVE. In addition, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is also used, and the EUS appearance of GAVE is described as spongiform mucosa and submucosa with well-preserved muscularis propria and hypertrophied gastric antrum. Red blood cell scan and CT scan findings of GAVE have also been described in a few case reports. Platelet marker CD61 immunostain identifies microthrombi within the vessels and increases the diagnostic accuracy of biopsy specimen evaluation.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrin thrombi and/or ectasia in mucosal vessels | Absent | Only one feature present | Both present |

| Spindle cell proliferation (smooth muscle cell and myofibroblasts hyperplasia) in superficial mucosal vessels | Absent | Increased | Markedly increased |

| Fibrohyalonosis around the ectatic capillaries of the lamina propria | Absent | Present | — |

Pathogenesis

GAVE is considered to be an acquired abnormality, resulting in ectasia of mucosal microvasculature, which results from mechanical stress or neuroendocrine abnormalities. Hemodynamic and autoimmune factors have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of GAVE and its exact cause remains to be further elucidated. The finding of antropyloric dysfunction and abnormal antral motor response to meals in some patients with GAVE relate to the hypothesis that repeated forceful peristalsis induces prolapse and trauma to the antral mucosa, which leads to microvascular abnormalities found in GAVE. Several neuroendocrine hormones (gastrin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide [VIP], 5-hydroxytryptamine, prostaglandin E2, nitric oxide, and/or glucagon) have also been suggested to play a role in the development of GAVE. Their levels are found to be elevated in some cirrhotics with GAVE. It is postulated that the accumulation of vasoactive substances that are poorly metabolized by the cirrhotic liver results in mucosal microvascular damage and ectasia. It is actually the loss of hepatic function rather than the portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis that is associated with GAVE, in contrast to PHG. GAVE has been reported to have completely resolved after liver transplantation, and portal decompressive techniques have been reported to not improve GAVE and its associated GIB. Up to 60% of GAVE patients have concurrent autoimmune disease (eg, Raynaud disease, systemic sclerosis, Sjogren syndrome) and several auto-antibodies have been detected in patients with GAVE. The association of several other chronic diseases (eg, renal, cardiac, and/or hematologic) with GAVE also needs further investigation.

Management

Similar to any patient with GIB, initial management of these patients consists of adequate resuscitation and hemodynamic stabilization. In patients with GAVE, GIB is most often chronic, with patients presenting with symptoms of anemia, occult blood in their stool, with or without iron deficiency anemia. GAVE is mostly identified as a part of the workup of GIB on upper endoscopy or during screening endoscopies. It is reasonable not to treat GAVE lesions, which are found incidentally or are not the source of bleeding (primary prophylaxis). For symptomatic/bleeding lesions, endoscopic ablative techniques are usually first-line treatment. Thermoablative procedures are used more commonly in clinical practice, while the use of cryotherapy, radiofrequency, or mechanical ablation is less frequent because, generally, they require more expertise.

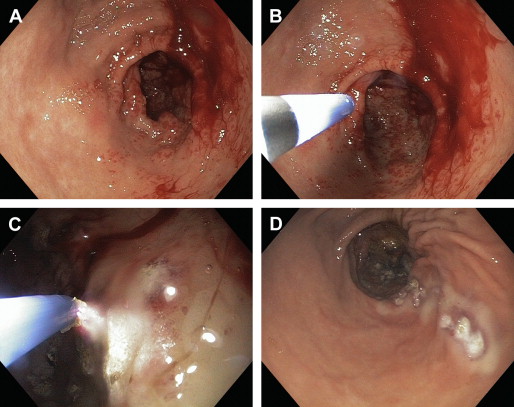

Major thermoablative techniques include argon plasma coagulation (APC) and neodymium:yettrium-aluminum garnet (YAG) laser therapies, which have been investigated extensively to control GAVE-related GIB. Both techniques are equally effective with up to 80% to 100% eradication of lesions and abolishment of need of blood transfusion in up to 50% to 80% of patients after 2 to 3 sessions on average. There are no head-to-head trials comparing these techniques; they do differ in their safety profile. APC is a reasonably newer ( Fig. 2 ), noncontact technique with lesser depth of coagulation and thus carries a lesser risk of gastric perforation as compared with YAG. YAG therapy is often complicated with gastric ulceration. In addition, cases of pyloric stenosis with gastric outflow obstruction, and hyperplastic gastric polyps forming after repeated sessions of YAG procedure, have been reported. A case of multifocal gastric cancer 5 years after multiple sessions of YAG laser therapy has also been reported. The technical details of these endoscopic procedures are not the focus of this article. The choice of procedure is mainly determined by the availability of expertise and technologies in any center. APC ablation is being used more prevalently these days because of better availability, lower cost, and good safety profile.

Endoscopic band ligation (EBL) for GAVE showed a significantly higher rate of bleeding cessation with fewer treatments sessions and reduced need for blood transfusions because of a greater increase in hemoglobin levels after treatment, as compared with endoscopic thermal therapy in a study by Wells and colleagues. This mechanical ablative procedure (EBL) has been reported in a few case reports ; however, its utility requires expertise, has not yet become popular in many centers, and requires further controlled trials before it can be recommended. In addition, several other endoscopic techniques including cryoablation (needs specialized equipment), bipolar coagulation probe (greater depth of energy delivery), endoscopic mucosectomy, and radiofrequency ablation have been attempted with encouraging results for refractory GAVE cases. These techniques also need larger, prospective studies before their general use, to establish their efficacy and safety.

Several classes of drugs have been used to control GAVE-related GIB in case reports and clinical studies. Generally, if endoscopic therapy is not effective or not feasible, medical options are possible. Hormonal therapy with estrogen-progesterone combination pills demonstrated cessation of GIB from GAVE. The GAVE lesions were not eradicated and patients required higher doses, as bleeding recurred with dose reduction during the follow-up period. Maintenance with higher-dose estrogen-progesterone might contribute to untoward side effects of hormonal therapy, including increased risk of endometrial and breast cancer. Octreotide is a somatostatin analogue and has multiple local neuroendocrine effects, including decreasing gastrin levels (growth factor for gastric mucosa), suppression of serotonin, VIP, secretin, motilin, and pancreatic polypeptide. These factors have all been implicated in the pathogenesis of GAVE. In addition, octreotide has been shown to decrease splanchnic circulation and has local anti-angiogenic effects. In addition, it has been shown clinically to effectively reduce the chronic bleeding from gastric vascular abnormalities. Its utility in GAVE still remains of unclear benefit. Other agents, like thalidomide, serotonin antagonists, tranexamic acid, and corticosteroids, have shown some clinical efficacy in separate case reports. Immunosuppressive therapies, methyl prednisone, and cyclophosphamide were used in a patient with systemic sclerosis and resulted in complete resolution of GAVE-related GIB, suggesting the importance of control of the underlying disease as definitive therapy for GAVE.

Surgical resection of the gastric antrum with Billroth-I anastomosis provides definitive cure and has been used in difficult-to-treat cases after endoscopic and medical failures. The analysis of several case reports revealed that a surgical approach (mainly antrectomy) carries up to a 6.6% 30-day mortality.

Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia in the Presence of Liver Cirrhosis

Liver cirrhosis is found in up to 30% of cases of GAVE. It often presents with chronic, persistent GIB leading to iron deficiency anemia. Overall, cirrhotic patients with GAVE-related GIB carry a higher mortality risk. It is often present with underlying portal hypertension and PHG. Diffuse/nodular pattern is more frequently seen along with PHG in cirrhotics, and clear distinction is sometimes difficult on endoscopic evaluation and, in such cases, careful biopsy and histologic evaluation are preferred. As mentioned above, the use of the GAVE score on histology has high diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing GAVE from PHG. This distinction is of clinical importance because management options are uniquely different for the definitive treatment of GIB from either of these gastric lesions. Treatment of portal hypertension (eg, β-blockers, or portosystemic shunts including transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt [TIPS]) does not have a significant effect on GAVE-related GIB. Endoscopic treatment is mostly the preferred option, APC therapy was found to be effective in 88% of patients with cirrhosis and it required fewer treatment sessions to completely control the GIB related to GAVE, as compared with those without cirrhosis. However, high mortality (53%) was observed in a study among cirrhotics during a 20-month follow-up period and was mostly related to hepatic decompensation. EBL has not been well studied in patients with liver cirrhosis and safety and efficacy of medical therapy has been well defined in this population. Abdominal surgery (antrectomy) carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality in cirrhotics, especially in patients with portal hypertension. Careful selection of patients, accurate diagnosis, and prompt treatment are prudent in cirrhotic patients with GIB related to GAVE. Liver transplantation resulted in complete resolution of GAVE in a patient despite persistent portal hypertension, possibly because of the cure of their underlying liver failure.

In summary, asymptomatic, nonbleeding GAVE lesions do not require any therapy. GIB should be managed with transfusions as needed with a hemoglobin target of 7 to 8 g/dL (cirrhotics) and iron replacements for iron deficiency anemia. Endoscopic therapy (APC) should be attempted first, followed by medical management if endotherapy fails. Surgery can be used in refractory cases of GIB, as a rescue therapy.

Portal hypertensive gastropathy

Epidemiology

As its name indicates, PHG is found in patients with portal hypertension. It is seen in patients with cirrhosis and also in cases of noncirrhotic portal hypertension. The prevalence of PHG, as mentioned in the literature, varies from 20% to more than 80%, with higher prevalence in decompensated cirrhosis as compared with patients with chronic hepatitis C and milder liver disease or those without cirrhosis. In addition, some report that PHG develops less frequently in patients who also have concomitant gastroesophageal varices ; however, some reports suggest that endoscopic ligation and sclerotherapy of varices increase the risk of developing PHG, albeit the risk is found to be temporary. Based on the diagnoses used, PHG is indicated to be the cause of 3% to 5% of chronic GIB and 2% to 12% of acute GIB in cirrhosis. Interestingly, from a large prospective study of nonresponder chronic hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis, the incidence of PHG is 12.9% per year and worsening PHG develops at a rate of 6.7% per year.

Diagnosis

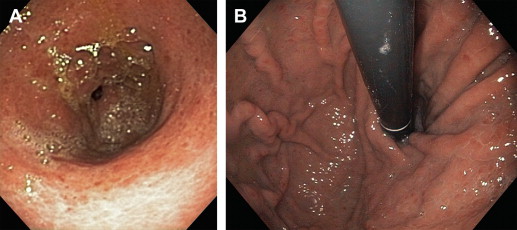

PHG is usually an incidental or a related finding on an upper endoscopy performed on cirrhotic patients for either variceal screening or acute GIB. It appears as a snake-skin-like mosaic pattern of the mucosa in milder forms and flat or raised red-brown spots in severe cases ( Fig. 3 ). Interobserver variability has been reported in the literature for the endoscopic diagnosis of PHG based on these morphologic patterns. If these mucosal lesions are biopsied, PHG usually demonstrates mucosal/submucosal ectatic vessels without thrombin clots or fibrinohyalonosis. As mentioned above, the absence of these findings and GAVE score will differentiate PHG from GAVE in difficult-to-diagnose cases. The distribution of PHG lesions is usually in the fundus and upper body of the stomach (see Fig. 3 ) and similar mucosal abnormalities are often found in the small (duodenopathy) or large (colopathy) intestine in patients with severe portal hypertension and/or liver cirrhosis. Capsule endoscopy has been used to help diagnose PHG and portal hypertensive lesions in distant parts of gastrointestinal tract. Recently, a few case reports have suggested indirect assessment of PHG either by blood testing or ultrasound examination. Moreover, transient elastography combined with platelet count is found useful for predicting the absence of esophageal varices and PHG in HIV patients with liver cirrhosis in a recent study.

Pathogenesis

Most studies have proposed portal hypertension as the essential underlying factor leading to PHG. Some investigators found mucosal friability and increased levels of local mediators leading to gastric mucosal injury, oxidative stress, and impaired healing. Typically, inflammation and vascular mural changes are not seen in the abnormally dilated vasculature seen in PHG lesions. Portal hypertension, when estimated by measuring the hepatic venous pressure gradient, has not demonstrated consistent correlation with the presence of PHG. Portal and systemic vascular hemodynamic alterations in patients with liver cirrhosis are found to be worse in patients who also have PHG as compared with those who do not have PHG. In addition, gastric mucosal blood flow abnormalities are also observed in PHG lesions independent of portal hypertension. There is no reliable indicator of severity of PHG, except that it is frequently persistent and progressive in patients with portal hypertension associated with liver cirrhosis, as compared with those with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Management

PHG is mostly asymptomatic, and the primary prophylaxis of GIB from nonbleeding PHG should be advised based on the presence and grading of gastroesophageal varices. In a study of patients with isolated nonbleeding PHG, 160 mg of long-acting propranolol per day for 6 weeks showed significant improvement in the endoscopic grading of PHG. Any patient with asymptomatic PHG should be followed with surveillance endoscopies per protocol, because PHG is found to worsen over time in up to 30% of patients. In patients with associated esophageal varices that require medical prophylaxis, the use of nonselective β-blockers could further potentially benefit those same patients with PHG. If PHG is identified in the setting of variceal bleeding and endoscopic therapy is applied for secondary prophylaxis of GIB, some studies have suggested that there is a transient worsening of PHG. In such cases, the introduction of β-blocker therapy could be of benefit to prevent worsening of PHG.

The most common presentation of PHG is chronic gastrointestinal blood loss and iron deficiency anemia (incidence around 10%–15% at 3 years). Adequate iron replacement and, as needed, blood transfusions are used to correct the anemia. Nonselective β-blockers have been shown to decrease recurrent bleeding episodes secondary to PHG. As secondary prophylaxis of bleeding from PHG, one study showed that propranolol is effective in the prevention of rebleeding during 30 months of follow-up. The dose of β-blocker should be titrated to the maximally tolerated dose for adequate heart rate control and minimal side effects. Although several studies have shown benefit of nonselective β-blockers (eg, propranolol, nadolol) in reducing portal hypertension, carvedilol, a nonselective β-blocker and α-1 receptor-blocker, has been shown to be superior to propranolol for reducing portal hypertension and associated GIB.

Acute GIB is an uncommon presentation of PHG (incidence <3% at 3 years) ; however, if it occurs, such bleeding episodes can be severe and difficult to manage. Initial management with appropriate resuscitation and antibiotic coverage should be individualized and promptly instituted. Systemic therapy with intravenous somatostatin, octreotide, terlipressin, and/or vasopressin has been shown to reduce portal hypertension and gastric blood flow and control bleeding in patients with PHG. Propranolol has been investigated for the acute management of bleeding from severe PHG and was shown to effectively control the GIB within 3 days. Use of β-blockers can be challenging in the acute setting because of systemic hypotensive and antisympathomimetic effects. Endoscopic therapy for acute bleeding from PHG may provide temporary control of GIB and remains investigational. APC application is proven successful in controlling bleeding from PHG and reducing transfusion requirements in a small study. Hemospray, a nanopowder hemostatic agent licensed for endoscopic hemostasis of nonvariceal UGIB in Europe and Canada, has been shown in preliminary data to be effective in stopping acute bleeding from portal hypertensive mucosal diseases. Hemospray has no effect on portal pressure or the underlying natural disease.

In cases of failure of medical or local therapies for acute or chronic GIB, patients that require frequent transfusions or are clinically worsening, portosystemic shunt therapies should be considered, either through surgery or through the placement of a TIPS. These shunts effectively decompress the portal system to terminate bleeding from PHG. A surgical shunt is preferred in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Patients who undergo shunt surgery have an improvement in the endoscopic appearance of the PHG lesions and a reduction in the number of transfusions required. Patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension who receive TIPS show an improvement of PHG lesions on endoscopy (in as short as 6 weeks after shunt placement and in up to 3 months) in cases with more severe PHG. Consideration of TIPS placement should be a team approach with the gastroenterologist, hepatologist, surgeon, and interventional radiologist involved in the decision-making process. TIPS placement carries a potential risk of rapid deterioration of hepatic function leading to liver failure and need for liver transplantation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree