Introduction

Antimicrobial prophylaxis is defined as the periprocedural systemic administration of an antimicrobial agent intended to reduce the risk of surgical site infection as well as secondary systemic infections [1]. Surgical site infections are a major contributor to patient injury, mortality, and healthcare costs and represent the focus of major national and international quality improvement projects. The prophylactic agent should be effective against the organisms that are characteristic of the operative site but should only be recommended when the potential benefit outweighs the risks and anticipated costs. In this chapter, we will systematically review the evidence for or against the use of prophylactic antibiotics in four commonly performed urological procedures.

The methods used in this chapter follow those developed by the GRADE Working Group [24]. We formulated four focused clinical questions which directed comprehensive literature searches for high-quality systematic reviews as well as relevant individual randomized controlled trials. Only studies comparing at least one treatment arm to a placebo or nontreatment control arm were included. Observational studies were not considered. Outcome variables were rated as critical, important or not important according to their importance to clinical decision making [5]. These ratings were consistent for all four clinical questions. The prevention of sepsis was considered a critical outcome according to GRADE. The prevention of fever, a new onset of unspecific urinary tract symptoms and positive urine cultures were rated as important yet not critical outcomes for clinical decision making. Expected side effects of short-term antibiotic prophylaxis were also considered as important yet not critical to decision making in this setting.

Study information was abstracted by a single reviewer and entered into RevMan. The quality of evidence informing each clinical question was rated on an outcome-specific basis as high, moderate, low or very low according to GRADE [2]. Dimensions of evidence quality considered were study limitations (appropriate randomization, allocation concealment, blinding, completeness of follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis and stopping early for benefit), inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. These steps were performed independently by two reviewers; disagreements were resolved by discussion and arbitration by a third reviewer. We performed formal meta-analyses and generated forest plots when appropriate while formally assessing for heterogeneity and publication bias. The information from RevMan was subsequently transferred into GRADEPRO and used to generate evidence profiles in the standard GRADE format.

Based on the outcomes deemed critical to clinical decision making, the quality of evidence was determined across outcomes. Recommendations were then formulated as either strong or weak (conditional), either for or against a given intervention. These recommendations were based on judgments about the balance of desirable and undesirable effects, the quality of evidence, the degree of certainty with which patients’ values and preferences were known and the anticipated costs of the intervention.

Clinical question 7.1

In patients undergoing ureteroscopy for ureteral stones, does antibiotic prophylaxis decrease the incidence of infectious complications when compared to no prophylaxis?

Literature search

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed (1966–2009) using the search terms “antibiotic prophylaxis,” “antimicrobial prophylaxis” and “ureteroscopy.” The search was limited to randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews in English, Spanish, German and French language with a human population.

The evidence

Two eligible randomized controlled trials were identified. A study by Fourcade et al. randomized 120 patients undergoing ureteroscopy for ureteral stones to cefotaxime 1 g IV versus placebo [6]. Interpretation of this study was made difficult by the inclusion of a subset of patients undergoing percutanous nephrolithotripsy that were not reported separately. A second, more recent study by Knopf et al. randomized 113 patients to 250 mg levofloxacin versus placebo [7].

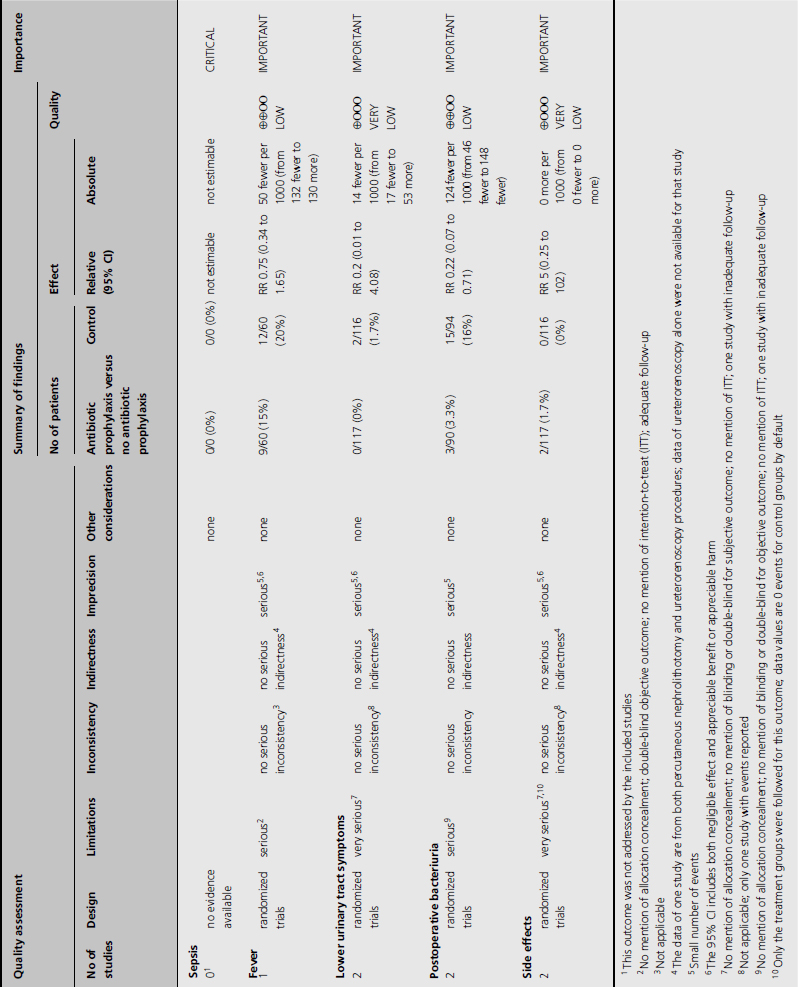

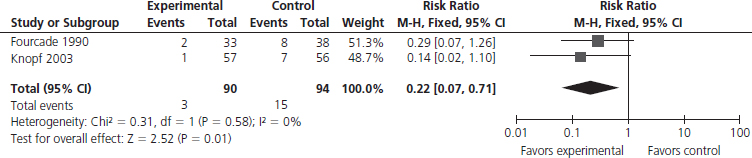

The available evidence is summarized in Table 7.1. A statistically significant benefit for the use of antibiotics in this setting was only documented for the incidence of positive cultures (Figure 7.1) which was reduced from 16% (15/94) to 3.3% (3/90), reflecting a relative risk (RR) of 0.22 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.07–0.71). The underlying quality of evidence was low with downgrading for study limitations as well as imprecision. Meanwhile, the rate of antibiotic-related side effects was low (1.7%) to mild in severity.

Table 7.1 GRADE evidence profile for Clinical Question 7.1: Should antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis be used in patients undergoing ureteroscopy?

Figure 7.1 Forest plot comparing antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing ureteroscopy to prevent postoperative positive urine cultures.

Clinical implications

Based on low-quality evidence, we make a conditional recommendation for the use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infectious complications in patients undergoing uncomplicated ureteroscopy for stone disease. The use of prophylactic antibiotics was not associated with a statically significant reduction of any adverse patient-important outcomes, although it reduced the rate of positive urine cultures, thereby indirectly supporting the use of antibiotics.

Clinical question 7.2

In patients undergoing shock-wave lithotripsy for the treatment of renal and ureteral calculi, does antibiotic prophylaxis decrease the incidence of infectious complications when compared to no prophylaxis?

Literature search

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed (1966–2009) using the search terms “antibiotic prophylaxis,” “antimicrobial prophylaxis” and “shock-wave lithotripsy.” The search was limited to randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews in English, Spanish, German and French language with a human population.

The evidence

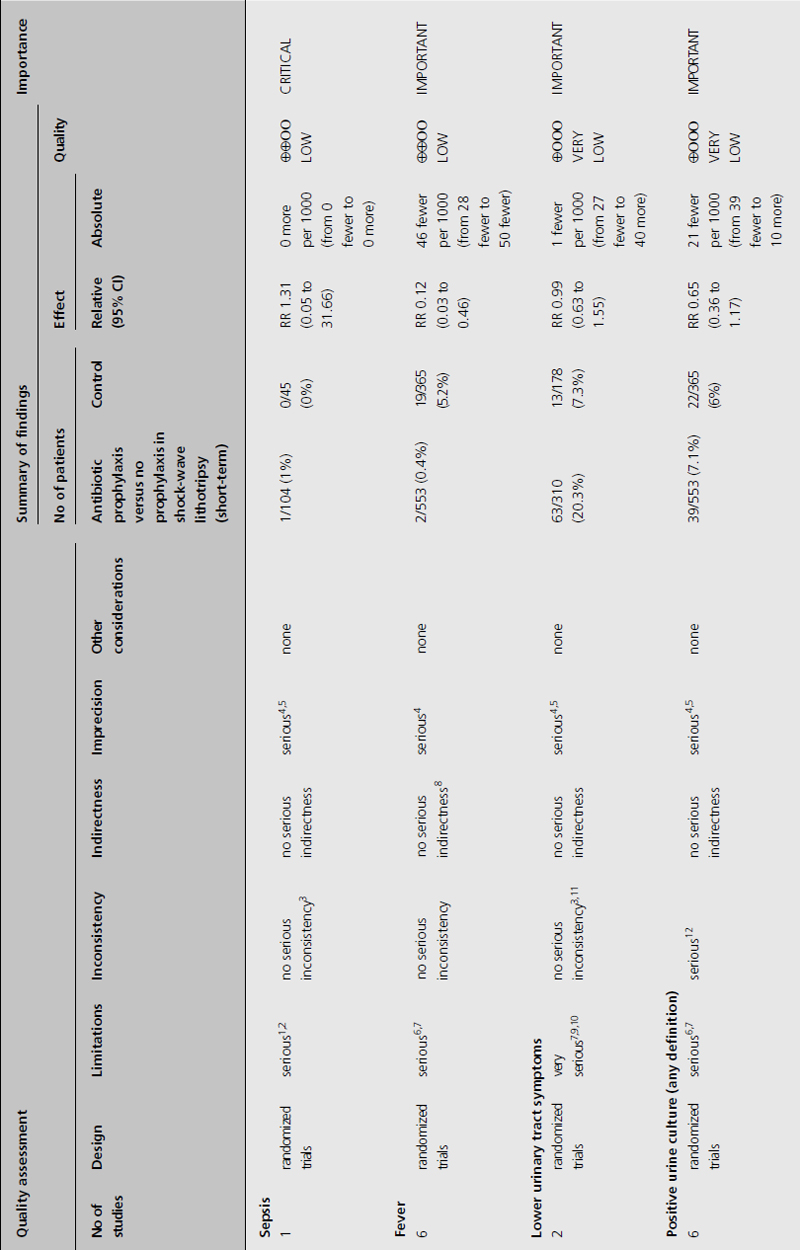

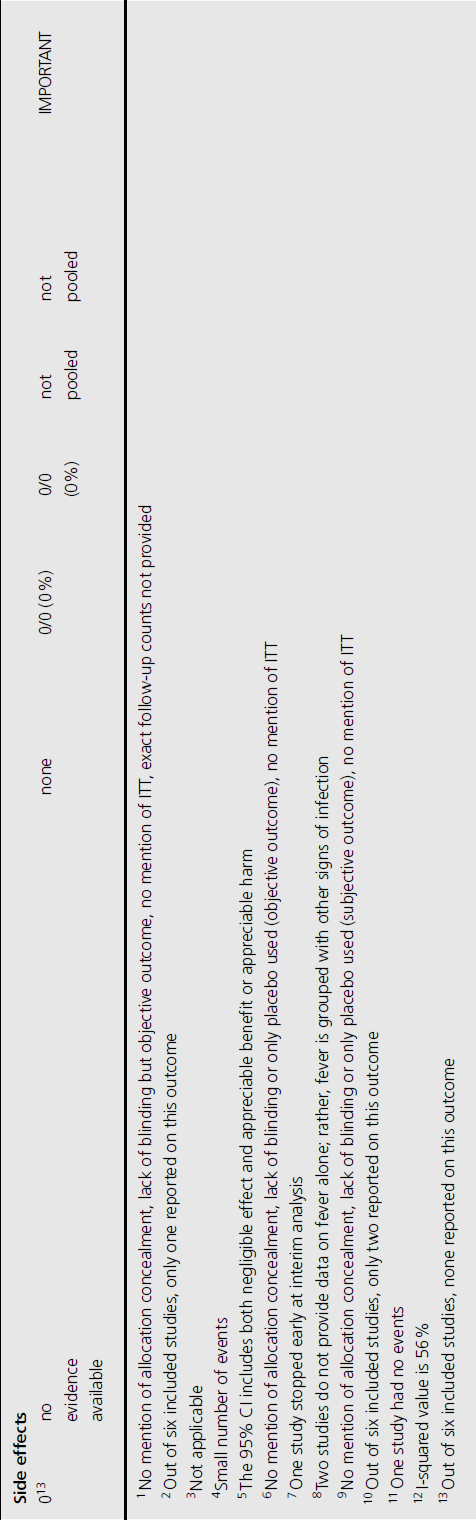

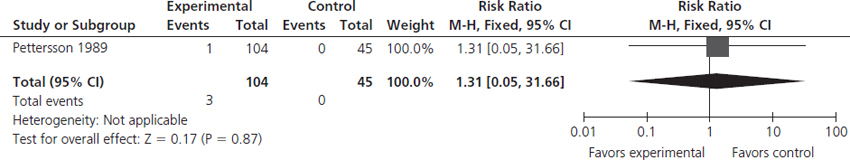

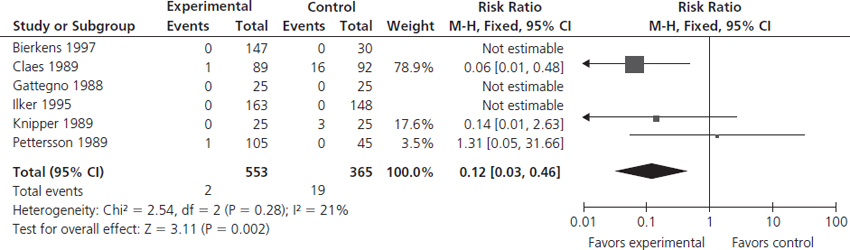

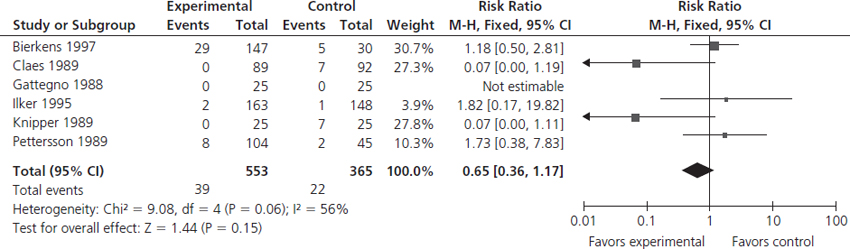

We identified a total of six randomized controlled trials addressing this clinical question [8–13]. All studies had methodological limitations as well as low event rates which led to downgrading to low- or very low-quality evidence for all relevant outcomes (Table 7.2). A single study by Pettersson & Tiselius [13] addressed the prevention of sepsis, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit, but also failed to exclude a potentially beneficial effect (Figure 7.2). All six studies addressed a reduction of febrile episodes with a calculated RR of 0.12 (95% CI 0.03–0.46; Figure 7.3) [8–13]. Antibiotic prophylaxis given to 1000 patients would therefore result in 46 fewer (95% CI 28 fewer to 50 fewer) patients with fever. However, no significant effect on the prevention of infection-associated lower urinary tract symptoms was demonstrated, nor was the number of positive urinary cultures significantly reduced (Figure 7.4). None of the studies addressed the incidence of side effects related to antibiotic prophylaxis.

Table 7.2 GRADE evidence profile for Clinical Question 7.2: Should antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis be used in patients undergoing shock-wave lithotripsy?

Figure 7.2 Forest plot comparing antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of sepsis in patients undergoing shock-wave lithotripsy.

Figure 7.3 Forest plot comparing antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of fever in patients undergoing shock-wave lithotripsy.

Figure 7.4 Forest plot comparing antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing shock-wave lithotripsy to prevent positive urine cultures.

Clinical implications

Based on the current best evidence, antibiotic prophylaxis is strongly recommended in patients undergoing shock-wave lithotripsy. This recommendation is based on low-quality evidence for a clinically important rate of reduction in the incidence of fever as a patient-important outcome. We assumed that the benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis clearly outweighed the risks, that there was relatively little variability with regard to relevant patients’ values and preferences related to the question of antibiotic prophylaxis, and that the costs of antibiotic prophylaxis were low.

Clinical question 7.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree