Anorectal Abscess

Vladimir Bolshinsky

Joseph Trunzo

Perioperative Considerations

Principles of Dealing with Perianal Sepsis

Irrespective of the complexity of perianal sepsis and potential associated fistula tracts, the initial step in the management of all patients is the same.

After obtaining a history and performing examination, either in the office or emergency setting, the patient is required to undergo an examination under anesthesia (EUA).

In the elective setting, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the perineum is sometimes helpful to further delineate the site of pelvic sepsis in cases with complex and multiple tracts. We prefer MRI to endoanal ultrasound due to its quality and interpretation that are more reproducible.

In the acute setting, most anorectal sepsis can be recognized on clinical examination, though a computed tomography (CT) can be useful to aid in deep space abscesses preoperatively. Acute abscesses most often simply need drainage, often done in the office under local anesthesia, with no MRI or added imaging at all.

Multiple EUAs may be required to adequately gain source control.

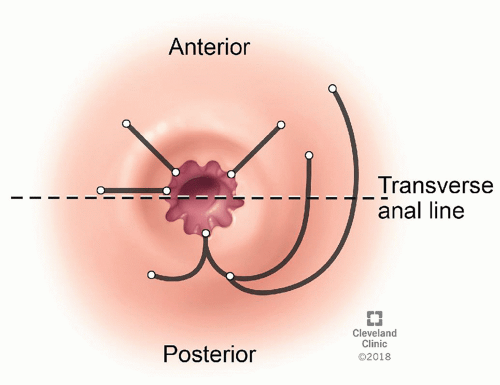

Half of perianal abscesses become fistulas. Classically, in a case of a simple cryptoglandular anorectal abscess, there is one abscess and one tract leading to a single internal opening. Goodsall rule (Fig 11-1) can be used to predict the internal opening and trajectory of the fistula tract based on the location of the external opening.

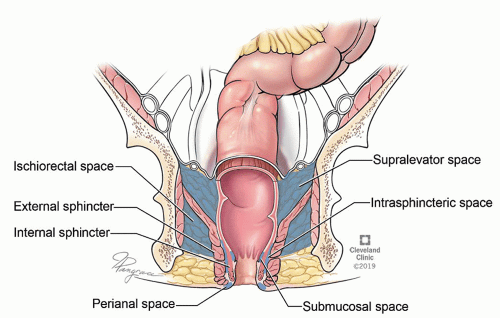

Understanding of the anatomy of the postanal space and appreciation of horseshoe abscess extensions due to the communication within the supralevator, ischioanal, and intersphincteric compartments are essential when dealing with complex anorectal sepsis (Fig. 11-2).

Sterile Instruments/Equipment

Equipment used for anorectal cases includes:

Set of fiberoptic-lighted Hill-Ferguson retractors: small, medium, and large

This is used for all perianal cases placed in lithotomy position.

Set of fiberoptic-lighted Fansler retractors: small, medium, and large

This is selectively used for perianal cases placed in prone (Kraske) position.

Set of Lockhart-Mummery fistula probes

Set of curettes

Vessel loops (to be used as seton)

Monopolar electrocautery

We routinely use 40 cut with 60 coagulation settings

A selection of Pezzer (ie, mushroom) drains

A selection of Penrose drains

Hydrogen peroxide

FIGURE 11-1 ▪ Goodsall rule. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2019. All Rights Reserved.) |

Technique

Positioning

The default position to perform an examination of the perineum and drainage of anorectal sepsis is in lithotomy with buttocks overhanging the edge of the operating table.

Prone jackknife position may be used for selected cases, although this is typically of most benefit for addressing anorectal fistulas with an anterior internal opening.

Examination under Anesthesia

Following appropriate positioning, the examination is commenced by close inspection of the perineum.

This may reveal undrained sepsis, previous scars, and external openings.

The clinician then proceeds to a digital rectal examination and an anoscopy. Our preferred retractor is a fiberoptic-lighted Hill-Ferguson with lubricant applied only to its convex surface.

Some surgeons prefer to do an anoscopy prior to digital rectal examination. A “bead of pus” from an anal crypt at the site of the dentate line may be the only sign of an internal opening.

Be mindful of Crohn disease, pilonidal cyst, and hidradenitis suppurativa as etiologies that may be mascarading as benign external openings of an anal fistula. Furthermore, an internal opening not located at the dentate line should warrant suspicion for Crohn disease, iatrogenic injury, or malignancy. Management of these conditions is described in the appropriate chapters of this textbook.

Sepsis in the deep postanal space may present without a visible abscess, or an identifiable internal opening. Posterior fullness on digital rectal examination may alert an astute examiner. A presacral tumor should be remembered as a differential in such a scenario. Ultrasound or MRI imaging and not aspiration is required in this setting.

Specific Considerations in the Management of Anorectal Abscess

Role of Antibiotics

We do not routinely give postoperative antibiotics, but consider treatment in patients who are immunocompromised, diabetic, or have associated cellulitis.

Optimal drainage should typically preclude the need for antibiotics in the absence of above.

In persistent cellulitis, consider the potential for undrained sepsis or another process.

Identification of a Fistula at the Time of Abscess Drainage

We do not probe the abscess cavity to identify a possible fistula in an index anorectal abscess, as we feel that the rate of iatrogenic fistula tract formation is underreported.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree