Fig. 6.1

Drawing of the anatomical location of the kidneys in the retroperitoneum (a) (© Carole Fumat); coronal macrosection from a formalin-fixed cadaver at the level of the adrenal space (b), just above the kidneys, crossing both the liver and spleen, and at the level of L1 (c), showing the perirenal and pararenal spaces and that the right kidney is lower than the left one (Courtesy of Prof. Giacomo Giacobini and Dr. Vittorio Monasterolo, Department of Neuroscience, University of Torino, Italy)

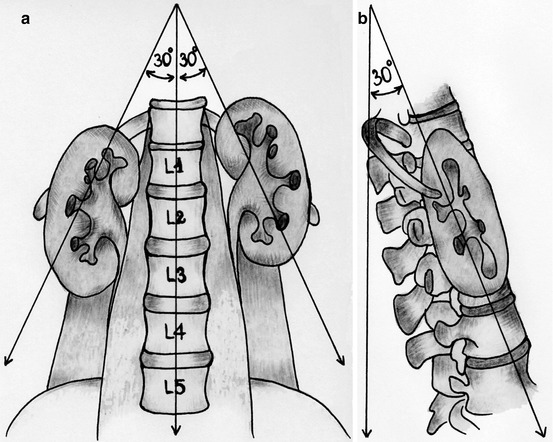

Their main axis is directed downwards, laterally, and anteriorly parallel to the oblique course of the psoas major muscles, with the superior poles closer to each other, more medial and more posterior than the inferior ones (Fig. 6.2a, b). Kidneys are angled 30°–50° behind the frontal coronal plane and their hilar region is rotated anteriorly with the lateral border rotated posteriorly (Fig. 6.3a, b). The supine or prone positions of the patient have no effect on the orientation of the kidneys [7].

Fig. 6.2

Kidney orientation on the frontal plane (a) and on the sagittal plane (b) (© Cracco)

Fig. 6.3

Kidney orientation on the coronal plane, drawing (a) (P posterior pararenal space, I intermediate perirenal space, A anterior pararenal space) (© Cracco) and picture from a coronal macrosection from a formalin-fixed cadaver (b) (Courtesy of Prof. Giacomo Giacobini and Dr. Vittorio Monasterolo, Department of Neuroscience, University of Torino, Italy)

The renal parenchyma basically consists of a cortex and a medulla. The medulla is characterized by 14–20 pyramidal structures, whose base is in contact with the cortex, and apex (also called renal papilla) directed to the renal sinus. It contains the loops of Henle and the collecting ducts, joining to form about 20 papillary ducts, opening at the area cribrosa papillae renalis, draining the urine out of the parenchyma into the renal collecting system. The cortex penetrates between two adjacent pyramids, giving rise to the renal columns (of Bertin). It contains the glomeruli with the proximal and distal convoluted tubules [8, 9].

6.3 Topographic Anatomy of the Kidney

The kidneys are a paired organ located in the retroperitoneum on the posterior abdominal wall, against the psoas major and the quadratus lumborum muscles, in a space surrounded by a connective sheath named Gerota’s or renal fascia. This space is closed cranially (where the sheaths are fused above the adrenal glands with the infradiaphragmatic fascia) and laterally (where the sheaths are fused behind the ascending and descending colon), whereas the anterior (prerenal fascia) and posterior (retrorenal fascia) sheaths of the fascia fade caudally in the retroperitoneum, weakly fused around the ureters, allowing renal fluid connections to drain into the sacral fossa. Laterally, Gerota’s fascia is continued by the subperitoneal fascia, located between the parietal peritoneum and the fascia transversalis. Medially, the posterior sheaths of the two sides fade in the prevertebral fascia (giving rise to the Zuckerkandl’s fascia), whereas the anterior ones join to each other ventrally to the blood vessels (aorta and inferior caval vein) forming the Toldt’s fascia immediately below the parietal peritoneum. Therefore it is rare that a hematoma, a urinoma, or an abscess of one side involves the contralateral side.

Between the Gerota’s fascia and the capsula fibrosa (renal capsule or true renal capsule) of the kidney, a though capsula which adheres to the organ, there is the perirenal adipose tissue (capsula adiposa), which surrounds the kidney and adrenal gland. The adipose tissue located anteriorly and posteriorly outside the renal fascia is the pararenal fat. Therefore there are three potential compartments created by the anterior and posterior layers of the renal fascia (Fig. 6.3a):

1.

The posterior pararenal space, containing only fat.

2.

The intermediate perirenal space, containing the adrenal glands, separated from the kidneys by an additional fascial layer, the kidneys, the proximal ureters and the perirenal fat.

3.

The anterior pararenal space, extending across the midline and containing the ascending and descending colon, the duodenal loop, and the pancreas.

6.4 Relationships with Neighboring Viscera

6.4.1 Posterior Relationships

The relations of the two kidneys are similar posteriorly:

The superior poles, to the upper limit of the renal sinus, lay on the diaphragm and, through it, are in contact with the costodiaphragmatic sinuses, the pleura, and the 12th rib (also the 11th rib on the left). Therefore, the diaphragm as well as the pleura is traversed by all intercostal renal punctures and also by some subcostal ones [10]. The lowermost lung edge lies above the 11th rib, at the 10th intercostal space regardless of the degree of respiration. With a supracostal 11th rib approach, the risk is 14 % on the left side and 29 % on the right side in prone position and 16 % on the left and 8 % on the right side in the supine position. A 10th rib supracostal approach is prohibitive, with more than 50 % risk of puncturing the lung [11]. Any intercostal puncture should be made in the lower half of the intercostal space, to avoid injury to the intercostal neurovascular bundles above, and also far from the vertebrae to avoid lung puncture because the lower margin of the lung is more horizontal than the axis of the ribs.

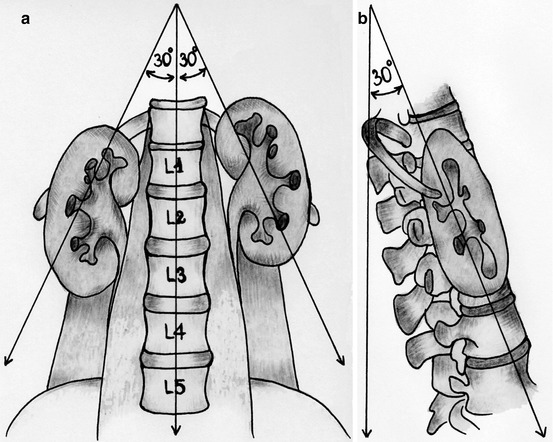

Fig. 6.4

Schematic drawing of the posterior relationships of the kidneys. PM psoas muscle, QLM quadratus lumborum muscle (© Cracco)

Medially, they lay on the fascia of the psoas muscle (Fig. 6.4).

Laterally, they lay on the quadratus lumborum and transversus abdominis muscles (Fig. 6.4).

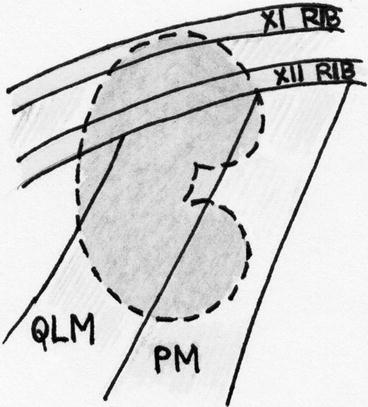

6.4.2 Anterior Relationships

Anteriorly (Fig. 6.5), the left kidney is in relation with the spleen (laterally), the stomach, the pancreas and the jejunum (medially), and the colon (at the inferior pole); the right kidney with the liver (the bare area), the duodenum (medially), and the colon (at the inferior pole).

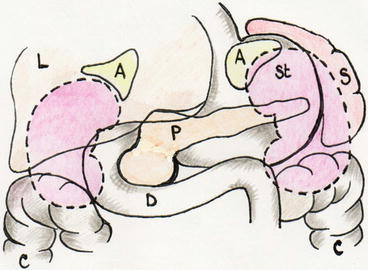

Fig. 6.5

Schematic drawing of the anterior relationships of the kidneys. A adrenals, S spleen, L liver, St stomach, C colon, P pancreas, D duodenum (© Cracco)

In mid- or full inspiration, especially in case of hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, the liver and spleen are displaced caudally, thus increasing the risk of lesion of puncture. The prone position displaces the colon posteriorly, with an increased risk of bowel injury, the supine one with the flank elevated 30° more anteromedially with a longer access tract (although a shortest distance may not necessarily be the best one). This happens because the anterior body wall is more compliant than the posterior one, so that in the prone position the anterior wall pushes the kidney backwards. The position of the retroperitoneal colon (that can be foreseen with the preoperative CT scan) is particularly relevant, being occasionally posterolateral or even posterior to the kidney, thus at risk of being injured in the percutaneous approach, especially to the inferior poles of the kidneys and when the patient is in the prone position (10 % versus 1.9 % in supine) [12–16].

On the superior pole, the adrenal glands are in contact, through the interposition of the interadrenorenal fascia, with the lower lateral side of the kidneys. Medially, the kidneys show a concavity, a deep groove, the renal sinus, which contains the renal hilum, through which the ureter/renal pelvis, renal artery, renal vein, lymphatic vessels, and nerves enter or exit the kidney. The renal hilum relates to the gonadal vessels and the aorta on the left and to the inferior caval vein on the right.

6.5 Renal Vascularization (Fig. 6.6)

Fig. 6.6

Isolated and fixed vascularization of the kidney. Veins in black, arteries in white (Courtesy of Prof. Giacomo Giacobini, Museum of Human Anatomy, Torino, Italy)

6.5.1 Arteries

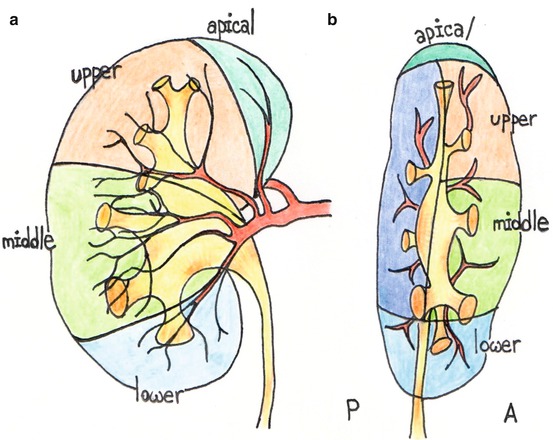

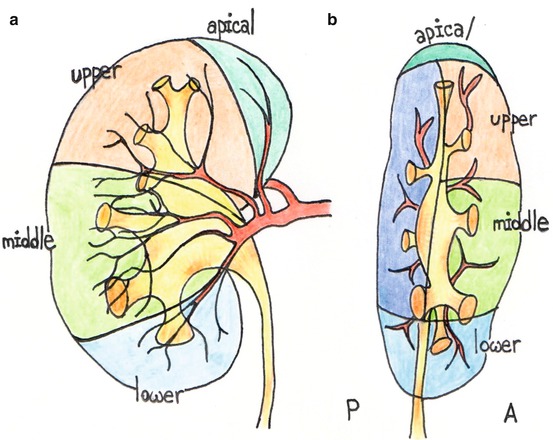

The distribution of the intrarenal arteries was described a long time ago in man [5, 8, 9] and divides the renal parenchyma into anatomic segments. In human kidney the anterior (ventral) and posterior (dorsal) ones are the most important segments. The pattern of kidney segmentation in humans has been described as formed by 4 or 5 arterial segments.

The renal artery, located in between the vein (anterior) and the pelvis (posterior), gives off the inferior suprarenal artery, then divides in an anterior and a posterior branch (Fig. 6.7). The posterior branch becomes the posterior segmental artery, to supply the homonymous anatomical segment of the kidney (50 % of the parenchyma). The anterior branch provides 3 or 4 segmental arteries for the superior pole, the anterosuperior segment, the anteroinferior segment, and the inferior pole.

Fig. 6.7

Schematic drawing of the anterior (A) and posterior (P) segmental distribution of the arterial renal branches, frontal (a) and lateral (b) views (© Cracco)

Before entering the parenchyma the segmental arteries give off the interlobar arteries, which enter in the renal columnae between the pyramids. Close to the base of the pyramids, they give off the arcuate arteries, usually by dichotomous division, which change direction turning parallel to the base. From the convex side of the arcuate arteries originates the interlobular arteries, which in turn originate the afferent arterioles of the glomeruli (Fig. 6.8b). In addition, from the efferent arteries of the glomeruli originate the arterioles rectae spuriae, whereas the rectae verae originate from the concavity of the arcuate arteries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree