Anal fissure is a common anorectal disorder resulting in anal pain and bleeding. Fissures can either heal spontaneously and be classified as acute, or persist for 6 or more weeks and be classified as chronic, ultimately necessitating treatment. Anal stenosis is a challenging problem most commonly resulting from trauma, such as excisional hemorrhoidectomy. This frustrating issue for the patient is equally as challenging to the surgeon. This article reviews these 2 anorectal disorders, covering their etiology, mechanism of disease, diagnosis, and algorithm of management.

Key points

- •

Anal fissure is arbitrarily classified as acute and chronic fissure, with the cutoff being nonhealing for 6 weeks or more.

- •

Whereas most acute fissures heal spontaneously, chronic anal fissures require treatment.

- •

The foundation of treatment relies on reversing internal sphincter hypertonia, thereby improving blood perfusion and promoting healing.

- •

Treatment options include:

- ○

Nonsurgical: ointments (nitroglycerin, diltiazem, nifedipine)

- ○

Chemodenervation: type A botulinum toxin

- ○

Surgical: lateral internal sphincterotomy

- ○

- •

Algorithm of treatment usually starts with ointments or chemodenervation. Given the possibility of anal continence compromise, surgery is used as a last resort for refractory, nonhealing fissures in patients with hypertonic sphincters.

- •

Mucosal advancement flaps are a viable surgical option for low-pressure fissures, or those at high risk for postoperative incontinence.

- •

The most common cause of anal stenosis is overzealous hemorrhoidectomy.

- •

Anal stenosis is classified based on the level, degree, and area of anal canal involved.

- •

Management of anal stenosis is challenging, and should be conducted by an experienced surgeon who is familiar with the disease.

- •

Management is tailored based on etiology and the level, degree, and area involved in stenosis.

Introduction: background, etiology, and pathophysiology

Anatomic and Physiologic Background

The functional anal canal starts at the anorectal ring and extends 3 to 4 cm to the anal verge. Proximally it is lined with columnar cells, which transition to squamous cells approximately 1 to 1.5 cm proximal to the dentate line; hence the term anal transition zone. Distal to the dentate line the multilayered squamous cell lining is rich with somatic nerves. Unlike skin, this area lacks sebaceous and skin glands and hair follicles, and is commonly referred to as the anoderm.

The anal canal lies at an angle with the rectum, owing to the effect of the sling-like puborectalis muscle around the rectum. The internal anal sphincter (IAS) is a thickened continuation of the longitudinal smooth muscle layer of the rectum. At rest the IAS is continuously contracted; is responsible for resting anal pressure, and causes passive continence. On defecation, the puborectalis muscle relaxes, resulting in straightening of the anorectal angle. The IAS relaxes, via the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, and the delicate pliable anoderm stretches and dilates to accommodate the passage of a column of stool.

Physiology of IAS Muscle Contraction

The IAS comprises smooth muscle fibers that are continuously contracted and regulated by the autonomic and enteric nervous systems. Contraction is mediated via an increase in cytoplasmic calcium. Conversely, a decrease in cytoplasmic calcium would result in relaxation.

β-Adrenoceptor stimulation induces the return of cytosolic calcium to the sarcoplasmic reticulum via cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which leads to muscle relaxation. Similarly, relaxation is induced by nonadrenergic, noncholinergic nitric oxide (NO), which is mediated via cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Alternatively, blocking direct influx of extracellular calcium through the membranes of calcium channels would achieve the same results; α-adrenoceptor stimulation leads to the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, resulting in contraction.

Epidemiology

Fissure in ano is a longitudinal or elliptical tear in the mucosal lining of the anal canal distal to the dentate line. At this location, the anoderm lining is composed of multiple layers of squamous epithelium and is richly innervated with pain fibers. Anal fissures (AFs) result in significant morbidity and reduction of quality of life in otherwise healthy young individuals.

Although fissures are more commonly encountered in a young age group, with equal ratio among both genders, they can also affect extremes of age. The exact incidence is unknown, likely because many patients with acute fissures do not seek medical advice, and improve without treatment. However, it has been suggested that the lifetime incidence is 11%.

Fissures are usually single, and lie in the posterior midline in 80% to 90% of cases. Anterior midline AFs are most commonly found in women. About 3% to 10% of AFs occur in the postpartum period, and these are often in the anterior midline.

Primary AFs are idiopathic, usually anterior or posterior, and are not caused by underlying disease. Secondary fissures often occur in the lateral positions and are associated with other disease processes. Multiple fissures should raise suspicion of other causes such as inflammatory bowel disease (mainly Crohn disease), human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, tuberculosis, cancer, or leukemia. Alternatively, fissures refractory to treatment should prompt examination under anesthesia and biopsy to rule out malignancy.

Primary fissures tend to occur more commonly in young age groups of both genders. Those fissures occurring in persons older than 65 years are more likely to be a secondary, so testing to rule out inciting pathology should be performed. AFs are arbitrarily classified as acute AF (AAF) and chronic AF (CAF) based on the duration of the disease process, with the cutoff being 6 weeks of persistent symptoms.

Etiology

Although AF is a commonly encountered anal problem, the exact etiology is poorly defined. The following mechanisms are thought to cause this condition.

Constipation and low-fiber diet

Trauma by passage of hard stool is thought to be an initiating factor. However, it has been reported that constipation occurs in only 1 in 4 patients; furthermore, in about 4% to 7% of instances fissure will follow bouts of diarrhea. Nevertheless, a low-fiber diet seems to be associated with an increased risk of developing a fissure.

Trauma during pregnancy

Up to 10% of chronic AFs occur postpartum, thought to be secondary to shearing forces from the fetus on the anal canal. Alternatively, the anal canal mucosa loses pliability and becomes tethered to underlying tissues, rendering it more susceptible to trauma while stretching during defecation. This type of AF tends not to be associated with high resting anal pressures.

Internal anal sphincter hypertonicity/spasm

As mentioned earlier, mean resting anal pressure (MRAP) is maintained by continuous contraction of the IAS. This contraction is mediated by α-adrenergic pathways as well as inherent myogenic tone. Once thought to be secondary to anal pain, high internal sphincter tonicity is now envisioned as a plausible cause of chronic AF. There has been evidence relating AF to high MRAP secondary to spasm of the IAS. Postmortem angiographic studies demonstrate relatively low perfusion at the posterior commissure of anal canal, where 90% of fissures are found. Doppler laser flowmetric study of the anodermal blood flow confirms the same findings. In healthy volunteers, the resting anal canal pressure is about 80 to 100 mm Hg, almost approaching the intra-arterial systolic pressure of the inferior rectal artery. Hypertonia of the IAS would impede blood flow, creating an area of relative ischemia and resulting in superficial ischemic ulcer (ie, AF). This correlation between abnormally high anal pressure and decreased anal blood flow is the foundation of AF treatment.

Introduction: background, etiology, and pathophysiology

Anatomic and Physiologic Background

The functional anal canal starts at the anorectal ring and extends 3 to 4 cm to the anal verge. Proximally it is lined with columnar cells, which transition to squamous cells approximately 1 to 1.5 cm proximal to the dentate line; hence the term anal transition zone. Distal to the dentate line the multilayered squamous cell lining is rich with somatic nerves. Unlike skin, this area lacks sebaceous and skin glands and hair follicles, and is commonly referred to as the anoderm.

The anal canal lies at an angle with the rectum, owing to the effect of the sling-like puborectalis muscle around the rectum. The internal anal sphincter (IAS) is a thickened continuation of the longitudinal smooth muscle layer of the rectum. At rest the IAS is continuously contracted; is responsible for resting anal pressure, and causes passive continence. On defecation, the puborectalis muscle relaxes, resulting in straightening of the anorectal angle. The IAS relaxes, via the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, and the delicate pliable anoderm stretches and dilates to accommodate the passage of a column of stool.

Physiology of IAS Muscle Contraction

The IAS comprises smooth muscle fibers that are continuously contracted and regulated by the autonomic and enteric nervous systems. Contraction is mediated via an increase in cytoplasmic calcium. Conversely, a decrease in cytoplasmic calcium would result in relaxation.

β-Adrenoceptor stimulation induces the return of cytosolic calcium to the sarcoplasmic reticulum via cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which leads to muscle relaxation. Similarly, relaxation is induced by nonadrenergic, noncholinergic nitric oxide (NO), which is mediated via cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Alternatively, blocking direct influx of extracellular calcium through the membranes of calcium channels would achieve the same results; α-adrenoceptor stimulation leads to the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, resulting in contraction.

Epidemiology

Fissure in ano is a longitudinal or elliptical tear in the mucosal lining of the anal canal distal to the dentate line. At this location, the anoderm lining is composed of multiple layers of squamous epithelium and is richly innervated with pain fibers. Anal fissures (AFs) result in significant morbidity and reduction of quality of life in otherwise healthy young individuals.

Although fissures are more commonly encountered in a young age group, with equal ratio among both genders, they can also affect extremes of age. The exact incidence is unknown, likely because many patients with acute fissures do not seek medical advice, and improve without treatment. However, it has been suggested that the lifetime incidence is 11%.

Fissures are usually single, and lie in the posterior midline in 80% to 90% of cases. Anterior midline AFs are most commonly found in women. About 3% to 10% of AFs occur in the postpartum period, and these are often in the anterior midline.

Primary AFs are idiopathic, usually anterior or posterior, and are not caused by underlying disease. Secondary fissures often occur in the lateral positions and are associated with other disease processes. Multiple fissures should raise suspicion of other causes such as inflammatory bowel disease (mainly Crohn disease), human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, tuberculosis, cancer, or leukemia. Alternatively, fissures refractory to treatment should prompt examination under anesthesia and biopsy to rule out malignancy.

Primary fissures tend to occur more commonly in young age groups of both genders. Those fissures occurring in persons older than 65 years are more likely to be a secondary, so testing to rule out inciting pathology should be performed. AFs are arbitrarily classified as acute AF (AAF) and chronic AF (CAF) based on the duration of the disease process, with the cutoff being 6 weeks of persistent symptoms.

Etiology

Although AF is a commonly encountered anal problem, the exact etiology is poorly defined. The following mechanisms are thought to cause this condition.

Constipation and low-fiber diet

Trauma by passage of hard stool is thought to be an initiating factor. However, it has been reported that constipation occurs in only 1 in 4 patients; furthermore, in about 4% to 7% of instances fissure will follow bouts of diarrhea. Nevertheless, a low-fiber diet seems to be associated with an increased risk of developing a fissure.

Trauma during pregnancy

Up to 10% of chronic AFs occur postpartum, thought to be secondary to shearing forces from the fetus on the anal canal. Alternatively, the anal canal mucosa loses pliability and becomes tethered to underlying tissues, rendering it more susceptible to trauma while stretching during defecation. This type of AF tends not to be associated with high resting anal pressures.

Internal anal sphincter hypertonicity/spasm

As mentioned earlier, mean resting anal pressure (MRAP) is maintained by continuous contraction of the IAS. This contraction is mediated by α-adrenergic pathways as well as inherent myogenic tone. Once thought to be secondary to anal pain, high internal sphincter tonicity is now envisioned as a plausible cause of chronic AF. There has been evidence relating AF to high MRAP secondary to spasm of the IAS. Postmortem angiographic studies demonstrate relatively low perfusion at the posterior commissure of anal canal, where 90% of fissures are found. Doppler laser flowmetric study of the anodermal blood flow confirms the same findings. In healthy volunteers, the resting anal canal pressure is about 80 to 100 mm Hg, almost approaching the intra-arterial systolic pressure of the inferior rectal artery. Hypertonia of the IAS would impede blood flow, creating an area of relative ischemia and resulting in superficial ischemic ulcer (ie, AF). This correlation between abnormally high anal pressure and decreased anal blood flow is the foundation of AF treatment.

Symptoms

Typically, AF presents with painful defecation described as a tearing sensation. Pain may persist a few minutes to hours following defecation, and can be accompanied by the passing of a modest amount of bright red blood that is usually separate from the stool. Larger amounts of blood could be a sign of another abnormality, such as hemorrhoids, as these 2 conditions may coexist. Blood mixed with stool should prompt further evaluation to rule out coexistent pathologic conditions.

Examination

On examination, patients are usually apprehensive and use their gluteal muscles as protection to avoid pain. Once relaxed, and with gentle separation of the buttocks, the tear can be visualized in the distal anal canal. The combination of pain and spasm often precludes digital rectal examination, and there is no need to subject the patient to a painful digital examination if the history and inspection confirm the diagnosis. If the diagnosis is in question, an examination under anesthesia is a less traumatic option by which to perform a thorough examination and obtain tissue samples.

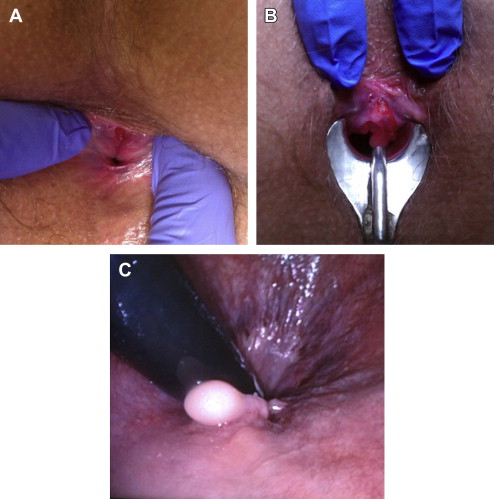

AAF is usually superficial, and has the appearance of a tear with well-delineated mucosal edges and a granulating base. Findings associated with chronicity include fibrotic rolled skin edges, sentinel tags, a hypertrophied anal papilla, visible transverse fibers of IAS at base of fissure, and duration of symptoms of at least 6 to 8 weeks.

Treatment

Acute Anal Fissures

AAFs are usually of short duration and more than 50% will heal spontaneously. The majority respond to a high-fiber diet and water intake to produce large bulky stool, resulting in physiologic anal dilation. Occasionally laxatives may be needed to soften the hard stool to avoid traumatic defecation. Warm sitz baths (up to 49 C as tolerable, 2–3 times a day, and/or after each bowel movement for 10–15 minutes) can help with symptomatic relief.

Topical hydrocortisone and anesthetic creams are less effective in relieving the symptoms of AAF. However, in one study 3 weeks of topical hydrocortisone resulted in healing rates comparable to those of fiber and sitz baths.

Chronic Anal Fissures

After 6 to 8 weeks without healing, fissures are classified as chronic. Only 10% of fissures that become chronic will spontaneously heal, meaning the majority will require some sort of treatment.

Management of CAF aims at treating the triad of anal pain, spasm, and ischemia by breaking the cycle of hypertonia-/spasm-induced ischemia. The goal is to lower the IAS pressure to improve perfusion while preserving continence.

Lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) ( Fig. 1 ) results in overwhelming cure rates upward of 98%, which has made surgery the mainstay therapy for CAF. However, early reports on this irreversible procedure showed concerns with regard to compromised anal continence in up to 30%. This finding prompted clinicians to seek medical alternatives that would reduce anal pressure without jeopardizing continence.

Different medical therapies have been tried, including NO donors (glyceryl trinitrate [GTN], isosorbide dinitrate), calcium-channel blockers (CCB), which cause the depletion of intracellular calcium, chemodenervation with botulinum neurotoxin A (BTX), muscarinic receptor stimulants, α-adrenergic receptor antagonists, and β-adrenergic receptor agonists.

Medical management

Nitric Oxide Donors

In both exogenous and endogenous forms, NO is a nonadrenergic, noncholinergic neurotransmitter that induces relaxation of the IAS.

NO stimulates guanylate cyclase, leading to formation of cGMP, which in turn activates protein kinases that ultimately dephosphorylate myosin light chains, resulting in muscle-fiber relaxation. A lack of NO synthase activity has been demonstrated in portions of IAS muscle fibers obtained from patients with AF. Soon after the inception of its role in relaxation of the internal sphincter, topical GTN was shown to impose a significant decrease in MRAP and improvement in blood flow to the fissure. Subsequently, several studies have evaluated the efficacy of GTN in treating AF ( Table 1 ).

| Authors, Ref. Year | Type of Study | Aim/Comparison | N | Dose | Duration of Treatment (wk) | Healing (%) | Headache (%) | F/U (mo) | Recurrence (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gorfine, 1995 | P | GTN in AAF | 15 | 0.5% qid | 8 | 80 | 33 | — | — | Efficient in AAF. Significant relief within minutes, lasting 2–6 h. HA self-limited |

| Lund et al, 1996 | P | Outcomes | 21 | 0.2% bid | 4 | 11 | 19 | — | — | Three of 4 recurrences (75%) healed with another course |

| 6 | 18 | |||||||||

| Lund et al, 1997 | RCT | GTN | 38 | 0.2% bid | 8 | 68 | 58 | 12 | 8 | Rapid relief; two-thirds avoid surgery; Recurrence treated with another course; Only 1 with HA withdrew |

| Placebo | 39 | 8 | 18 | |||||||

| Bacher et al, 1997 | RCT | GTN vs | 20 | 0.2% tid | 4 | 80 | — | — | — | CAF healing rates were 62% and 20%, respectively |

| Lidocaine | 15 | 2% | 40 | |||||||

| Oettle, 1997 | RCT | GTN vs | 12 | 0.5 mg tid | 2–4 | 83 | — | Median 22 | — | GTN healers had fast relief |

| IS | 12 | 100 | GTN may reduce need for IS | |||||||

| Lund & Scholefield, 1997 | P | Outcomes | 39 | 0.2% bid | 4 | 36 | 20 | — | 13 | Healing rate increased significantly at 6 wk. 4 of 5 recurrences healed with another course |

| 6 | 85 | |||||||||

| Kennedy et al, 1999 | RCT | GTN vs | 24 | 0.2% bid | 4 | 46 | 29 | Mean 28 | 62 | IAS pressure increased after completion of treatment; 40% of recurrences healed with another course; 60% long-term healing rate |

| Placebo | 19 | 16 | 20 | |||||||

| Carapeti et al, 1999 | RCT dose finding | GTN vs | 23 | 0.2% tid | 8 | 65 | 65 | Median 9 | 33 | Good alternative for 2 out of 3 patients. Escalating dose did not result in earlier healing. High recurrence. High HA |

| ↑ Dose GTN | 23 | — | 70 | 78 | 25 | |||||

| Placebo | 22 | 0.2%–0.6% tid | 32 | 27 | 43 | |||||

| Altomare et al, 2000 | RCT role in AF | GTN vs | 59 | 0.2%/12 h | 4+ | 49 | 39 | — | 19 | GTN: significant increase in anodermal blood flow. Cannot substitute IS |

| Placebo | 60 | 51 | 6 | |||||||

| Zuberi et al, 2000 | RCT | Topical vs | 18 | 0.2% tid | 8 | 67 | 72 | — | — | GTN patch is equally effective as GTN |

| Patch | 19 | 63 | 63 | |||||||

| Is | 12 | 92 | — | |||||||

| Pitt et al, 2001 | P | Predictors of failure | 64 | 0.2% bid | Until healing or IS | 41 | 64 | 15 | 46 | Sentinel pile adversely affects outcome. 15% with HA withdrew |

| Skinner et al, 2001 | P | Outcomes | 51 | 0.2% qid | 4 | 34 | 18 | — | — | IS remains treatment of choice. 18% HA withdrew |

| Bailey et al, 2002 | RCT | GTN dose/frequency. 8 groups | 304 | 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4% (0–1.5 mg) bid and tid | 8 | Equal healing 50% | — | — | — | Reduced pain with 0.2 and 0.4% bid and tid |

| Scholefield et al, 2003 | RCT dose response | 181 | 49 | 0.1 | 8 | 47 | 20 | — | — | Increased healing in placebo reflects problem in definition of chronicity |

| 47 | 0.2 | 40 | 42 | |||||||

| 37 | 0.4 | 54 | 90 | |||||||

| — | All bid | 37 | 12 | |||||||

| Gagliardi et al, 2010 | RCT optimal duration of treatment | 74 | 74 | 0.4% bid | 6 | 55 | 23 | — | — | Overall healing 58%. Healing increased significantly around 6 wk. 8% withdrew due to HA |

| 79 | 79 | 12 | 53 | |||||||

| Perez-Legaz et al, 2012 | RCT | Endoanal | 26 | 0.4% bid | 8 | 23 | — | 6 | — | Healing at 6 mo: 77% and 62%. Disabling HA in 15% of perianal group |

| Perianal | 26 | 54 |

Overall, healing rates with a dose of 0.2% applied twice a day ranged from as low as 18% to as high as 85%. As noted in Table 1 , lower rates are observed in studies with duration of treatment of 6 weeks. In randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with duration of therapy of 6 to 8 weeks, the average healing rate was 50% to 68%. The rate of noncompliance ranged from 8% to 18%, related primarily to nitrate-induced headache. Gagliardi and colleagues evaluated optimal treatment duration using 0.4% topical GTN twice daily. Healing increased significantly in the first 6 weeks of therapy. However, they found no gained benefit on extension of the duration of therapy from 6 weeks to 12 weeks. Similarly, Lund and Scholefield demonstrated an increase in healing rates from 36% to 85% from 4 to 6 weeks of treatment, respectively.

The most common side effect of topical GTN is headache, occurring in 20% to 90% of patients. It is usually transitory, and subsides within 15 minutes. Headache may be managed by educating patients before treatment, starting with a lower dose and escalating over 4 to 5 days, using finger cots for application to minimize the absorptive area, applying ointment in the recumbent position, and staying in this position for about 15 minutes after application. Nevertheless, in approximately 10% to 15% of patients, headache is disabling and results in discontinuation of treatment.

It has been demonstrated that CAF may heal faster with higher dosages/concentrations of NO donor ointments; however, this effect does not translate into superior healing rates in the long term. In addition, the higher-dosed NO donors increase the incidence of headaches and orthostatic hypotension, which may influence compliance. The effect of GTN on the IAS is reversible, and lacks a long-term effect on MRAP with subsequent increase in anal pressure on discontinuation. This drawback explains the incidence of relapse, which is as high as 30%. Again, higher rates were observed in studies with duration of therapy of less than 6 weeks. Graziano and colleagues correlated the recurrence to persistent hypertonia, and reported that CAFs were more likely to recur in the presence of a sentinel tag. However, a significant amount of relapsing fissures healed with a repeat course of GTN, which further increased the overall rate of healing to 70%.

Calcium-Channel Blockers

CCBs act by inhibiting voltage-dependent calcium channels located in the plasma membrane of electrically excitable muscle cells. Blocking these channels leads to a decrease in sarcoplasmic calcium ion concentration. The decrease in calcium interferes with calcium-mediated signal transduction and phosphorylation, ultimately decreasing contraction and resulting in the relaxation of muscle fibers.

CCBs, often used in the treatment of cardiovascular disease, are also an effective treatment used to relax the lower esophageal sphincter in esophageal achalasia. The same concept was applied in treating CAF when diltiazem (DTZ) 2% topical gel was used to reduce IAS pressure, which achieved a healing rate of 67%. Table 2 highlights multiple studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of DTZ and nifedipine (NFDP).

| Authors, Ref. Year | Type of Study | Aim/Comparison | N | Dose | Duration of Treatment (wk) | Healing (%) | Side Effects (%) | F/U (mo) | Recurrence (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carapeti et al, 2000 | P | DTZ | 15 | 2% | 8 tid | 67 | — | — | — | Similar healing to GTN, ↓ side effects. No difference in MRAP between responders and nonresponders |

| GTN | 15 | 0.1% | 60 | — | — | — | ||||

| Jonas et al, 2001 | RCT | Topical | 26 | 2% bid | 8 | 65 | 0 | — | — | No significant ↓ in BP. Retains healing ability but ↓ healing rate, and more side effects |

| PO | 24 | 60 mg | 38 | 33 | ||||||

| Das Gupta et al, 2002 | P | DTZ gel | 23 | 2% | 6–8 tid | 48 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Similar healing rates, ↓ side effects. Healed 75% (6/8) of patients who previously failed GTN |

| Kocher et al, 2002 | RCT | DTZ | 31 | 2% | 6–8 bid | 77 | 42 | — | — | Similar healing rates. Significant ↓ side effects and HA |

| GTN | 29 | 0.2% | 86 | 72 | ||||||

| Griffin et al, 2002 | Cohort | DTZ after failing GTN | 46 | 2% | 8 bid | 48 | — | — | — | Heals and further avoids surgery in about 50% in those failed on GTN |

| Jonas et al, 2002 | P | DTZ outcomes | 39 | 2% | 8 bid | 49 | 10 | — | — | 27 of 39 failed previous GTN with 44% healing.10% side effects, mainly perianal itching |

| Bielecki & Kolodziejczak, 2003 | RCT | DTZ | 22 | 2% | 8 bid | 86 | 0 | — | — | Equally effective. ↓ side effects |

| GTN | 21 | 0.5% | 85 | 33 | ||||||

| Shrivastava et al, 2007 | RCT | DTZ | 31 | 2% | Bid till healing | 80 | 0 | — | 12 | Both are effective modalities. DTZ ↑ healing, delayed recurrence (5.5 vs 3.5 mo) |

| GTN | 30 | 0.2 | 73 | 67 | 32 | |||||

| Placebo | 30 | — | 33 | 0 | 50 | |||||

| Sanei et al, 2009 | RCT | DTZ | 51 | 2% | 12 bid | 66 | — | — | — | DTZ significant reduction of symptoms. GTN faster healing |

| GTN | 51 | 0.2% | 55 | |||||||

| Jawaid et al, 2009 | RCT | DTZ | 40 | 2% | 8 bid | 77 | 32 | — | — | Equally effective, DTZ may be first line due to ↓ side effects |

| GTN | 40 | 0.2% | 82 | 72 | ||||||

| Ala et al, 2012 | RCT | DTZ | 36 | 2% | 8 bid | 91 | 0 | — | — | Superior healing rate. ↓ side effects |

| GTN | 25 | 0.2% | 60 | 100 | ||||||

| Nifedipine | ||||||||||

| Cook et al, 1999 | P | PO NFDP | 15 | 20 mg bid | 8 | 91 | 100 | — | — | Early ↓ in BP, resolved by 4th wk. ↓ in MRAP. 10 patients had flushing and 5 had HA |

| Volunteers | 8 | 15 | ||||||||

| Perrotti et al, 2002 | RCT | NFDP + Lido | 55 | 0.3% + 1.5% | 6 bid | 94 | — | 18 | 6 | Efficient combination. ↓ side effects. ↓ MRAP. Repeat course leads to further healing |

| Lido + HC | 55 | 1.5% + 1% | 16 | |||||||

| Ansaloni et al, 2002 | P | PO NFDP | 21 | 6 mg daily | 4 | 90 | 33/2 wk | 2 | — | No changes in BP. Promising alternative. RCT and Long-term results needed |

| Ezri & Susmallian, 2003 | RCT | NFDP | 26 | 0.5% | 8 bid | 89 | 5 | 3 | 42 | More effective. ↓ HA. Frequent recurrence in both groups |

| GTN | 26 | 0.2% | 58 | 40 | 4.5 | 31 | ||||

| Agaoglu et al, 2003 | P | NFDP | 10 | 20 mg bid | 8 | 50 | 10 | — | — | No significant drop in BP. An alternative. Significant ↓ in MRAP |

| Volunteers | 10 | |||||||||

| Golfam et al, 2010 | RCT | NFDP | 60 | 0.5% | 4 | 70 | — | 12 | 26 | Significant healing and pain control rates. ↑ Recurrence |

| Lidocaine | 50 | 2% | 12 | |||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree