ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Harmful alcohol consumption is defined as more than 4 drinks on any single day or more than 14 drinks per week for men, while for women the threshold is more than 3 drinks on any single day or more than 7 drinks per week.

In the United States, a standard drink is defined as any drink that contains about 14 g of pure ethyl alcohol.

More than 60% of adult Americans consume alcohol in a more or less regular fashion, and it is estimated that 18 million Americans have an alcohol use disorder.

The spectrum of alcoholic liver disease ranges from alcoholic steatosis to alcoholic cirrhosis, while alcoholic hepatitis may occur episodically in the absence or presence of advanced liver disease.

Virtually everyone with excessive alcohol intake has alcoholic steatosis, while 10–15% of the affected population develop alcoholic cirrhosis and 10–35% develop one or more episodes of symptomatic alcoholic hepatitis.

Patients with alcoholic liver disease are at increased risk of hepatocellular cancer, with an incidence rate of 1–2% per year among patients with cirrhosis.

Alcoholic liver injury is suggested by increased serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels with an AST/ALT ratio exceeding 2.0.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Alcohol (ethyl alcohol, ethanol, CH3CH2OH) is one of the most common hepatotoxic agents and humans have consumed it since prehistoric times. Alcoholic liver disease develops in virtually everyone who is engaged in excessive use of alcohol, although the severity of hepatic injury may vary considerably. While steatosis is almost always present, alcoholic liver disease evolves into cirrhosis in 10–15% of the affected population. Patients with advanced alcoholic liver disease are also at risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, which may develop with an annual risk of 1–2%. The natural course of alcoholic liver disease may be complicated by episodes of symptomatic alcoholic hepatitis, which occurs in 10–35% of patients with excessive alcohol consumption. This wide spectrum of alcoholic liver disease outcomes is a result of the complex interplay between variables including the amount of alcohol consumed, the pattern of drinking, individual genetic predisposition, and the presence of comorbidities.

In the United States, the population aged 15 years and older had an annual per capita alcohol consumption of 9.2 L of pure alcohol between 2008 and 2010. More than 60% of adult Americans consume alcohol in a more or less regular manner and it is estimated that 18 million Americans have an alcohol use disorder, classified as either abuse or dependence. Epidemiologic studies have established a dose-effect relationship between alcohol intake and alcoholic liver damage. While any amount of alcohol could have adverse health effects, epidemiologic evidence supports recommendations for a threshold amount of regularly consumed alcohol above which the risk of physical and mental health impairment is increased. In the United States, harmful alcohol consumption has been defined as more than 4 drinks on any single day or more than 14 drinks per week for men, while for women the threshold is more than 3 drinks on any single day or more than 7 drinks per week. In this schema, a standard drink denotes any drink that contains about 14 g of pure alcohol.

Alcohol consumption has a profound economic and health impact, with more than 200 health conditions and an estimated 5.1% of the global disease burden attributable to the consumption of alcohol. In 2012, the World Health Organization estimated that 3.3 million fatalities, or 5.9% of all deaths in the world, were linked to alcohol consumption. Alcohol represents the third largest cause of disability in the United States with an estimated overall cost exceeding $234 billion or 2.7% of the GDP in 2012.

[PubMed: 9462221]

[PubMed: 15194200]

[PubMed: 15535449]

[PubMed: 15508108]

[PubMed: 20034030]

[PubMed: 23511777]

PATHOGENESIS

In most cases, excessive alcohol consumption is associated with steatosis only, suggesting the importance of individual risk factors in the development of advanced liver disease such as alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis. Sex, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors appear to have a major impact on the degree of alcohol-induced hepatotoxicity. Ample evidence indicates that women are more susceptible to the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol than are men, and this has been linked to gender differences in the metabolism of alcohol. In women, higher body fat content results in lower volume of distribution and delayed elimination of alcohol, while lower gastric acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity may allow increased delivery of alcohol to the portal circulation. Several observations suggest the role of race and ethnicity in the severity and progression of alcoholic liver disease. For instance, mortality rates of alcoholic cirrhosis in the United States are highest among white Hispanic males and black non-Hispanic females. Importantly, socioeconomic factors may contribute to these ethnic differences by affecting at-risk drinking behavior and limiting access to health care.

Twin studies in which alcoholic cirrhosis was more prevalent among monozygotic than dizygotic twin pairs support the role of genetic factors in alcoholic liver disease. Individual susceptibility to alcohol-induced hepatotoxicity may be modified by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of genes involved in the regulation of alcohol metabolism, lipid storage and utilization, oxidative stress and inflammation, and the development of addiction. Some of the most prominent mutations implicated in this mechanism are listed in Table 43–1.

| Function | Gene | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol dependence | γ-aminobutyric acid receptor subtypes (GABRA2) | Altered withdrawal, aversion, positive reinforcement |

| Alcohol metabolism | Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2*2) | Altered alcohol metabolism, flush syndrome, and avoidance of alcohol (prevalent in Asians) |

| Oxidative stress | Microsomal cytochrome P450 (CYP2E1) Glutathione S-transferase (GST) Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) | Altered detoxification capacity, increased hepatocellular injury, stimulation of oncogenic pathways |

| Endotoxin pathways | Endotoxin receptor (CD14) Interleukin-10 (IL10) Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) | Altered recognition of molecular patterns associated with pathogens and cell damage |

| Lipid storage and utilization | Adiponutrin (PNPLA3) Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ (PPARG) Apolipoprotein E (APOE) | Altered pathways of lipid metabolism |

Harmful effects of excessive alcohol consumption may be significantly enhanced by the presence of coexisting chronic liver disease, resulting in faster disease progression and worse disease outcomes. Alcoholic liver disease increasingly co-occurs with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) due to the dramatically rising prevalence of obesity and diabetes. Overweight or obesity persisting for at least 10 years independently increased the risk of developing cirrhosis among 1604 French patients with biopsy-proven alcoholic liver disease by an odds ratio of 2.5. In an American single-center study, diabetes was associated with a 10-fold higher risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma among individuals with heavy alcohol consumption. Similarly, the pathogenic synergy between alcohol and chronic hepatitis C can result in increased hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication, impaired dendritic cell function, and diminished interferon response, supporting the emergence of HCV quasispecies and promoting increased rates of fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis.

Alcohol consumption appears to increase the risk of acetaminophen-induced liver injury. This is because alcohol augments the accumulation of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), the hepatotoxic metabolite of acetaminophen, by stimulating its production via the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 2E1 (CYP2E1) and blocking its elimination by depleting intracellular glutathione stores. It is therefore recommended that the daily dose of acetaminophen should not exceed 2 g for those who drink alcohol. Similar dose reduction is advisable in the setting of alcoholic cirrhosis even in the absence of ongoing alcohol consumption.

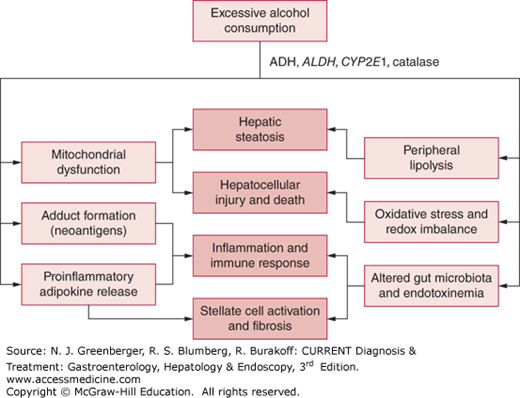

Alcohol is mostly metabolized in the liver into the highly toxic acetaldehyde by cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and to a lesser extent by the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS). Acetaldehyde is a highly toxic molecule that may covalently bind to various macromolecules and activate the innate immune response by novel epitopes of protein adducts and other damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Moreover, mitochondrial catabolism of acetaldehyde shifts the redox balance and interferes with lipid utilization pathways, leading to hepatic steatosis. Microsomal oxidation of alcohol occurs primarily through CYP2E1, which is markedly induced by chronic alcohol consumption and contributes to the generation of intracellular free oxygen radicals.

Chronic alcohol consumption interferes with insulin-mediated regulation of peripheral lipolysis, contributing to hepatic lipid accumulation. Moreover, metabolism of alcohol by enteral bacteria may increase local acetaldehyde levels and weaken the integrity of mucosal tight junctions, promoting intestinal permeability and increasing the absorption of endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The increased portal levels of LPS and other pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) then activate Kupffer cells and contribute to the liver inflammatory response. Major mechanisms in the pathophysiology of alcoholic liver disease are summarized in Figure 43–1.

Figure 43–1.

Pathophysiology of alcoholic liver disease. This schematic diagram illustrates molecular mechanisms promoted by the intake and metabolism of alcohol in the liver, adipose tissue, and gastrointestinal tract (light boxes), contributing to characteristic pathologic changes in alcoholic liver disease (dark boxes).

[PubMed: 22229098]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree