- Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a common condition in kidney specialist practice with significant complications. It is caused by a wide range of primary (idiopathic) and secondary glomerular diseases.

- Patients can present in various clinical settings, with not insignificant numbers undergoing community-based treatment with care shared between specialists and primary care.

- All patients need referral to a nephrologist for further investigation with a renal biopsy.

- Initial management should be focused at investigating its cause, identifying complications and managing the presenting symptoms of the disease.

- No conclusive evidence currently exists for the best treatment strategies for most primary glomerular diseases.

Nephrotic Syndrome

The nephrotic syndrome (NS) is one of the best-known presentations of adult or paediatric kidney disease (Orth and Ritz 1998). It describes the association of heavy proteinuria with peripheral oedema, hypoalbuminaemia and hyperlipidaemia (Box 7.1, 7.2). NS has multiple causes, significant complications and requires referral to a nephrologist for further investigation and management. Patients can present de novo in various clinical settings, with not insignificant numbers of patients undergoing community-based treatment, with management shared between specialists and primary care (the paradigm for much of renal medicine in the twenty-first century).

- Greater than 3–3.5 g/24 hr proteinuria or spot urine PCR of > 300–350 mg/mmol

- Serum albumin < 25 g/L

- Clinical evidence of peripheral oedema

- Can also be associated with hyperlipidaemia (raised total cholesterol) and lipiduria

- Transient increased proteinuria can be seen in fever, post-exercise, post-seizure, in severe acute illnesses

- Persistent proteinuria of > 150 mg/day (PCR ∼ 10–20 mg/mmol) implies renal or systemic disease

- Dipsticks predominantly detect urinary albumin (and are positive if excretion is > 300 mg/day)

Though NS is a common condition in nephrological practice and should feature in the differential diagnosis of any oedematous patient, there can be uncertainty about how best to manage it. In part this is due to a lack of randomized controlled trials, and the presence of only a handful of Cochrane systematic reviews.

This chapter provides an update on the management of NS in adults. We review relevant investigation and therapeutic strategies for the general condition of NS, and for some of the primary glomerular causes (but we deliberately avoid highly specialized or recherché conditions). In particular, our approach emphasizes the clinical challenges faced by doctors without specialized renal experience when presented with a patient with suspected NS.

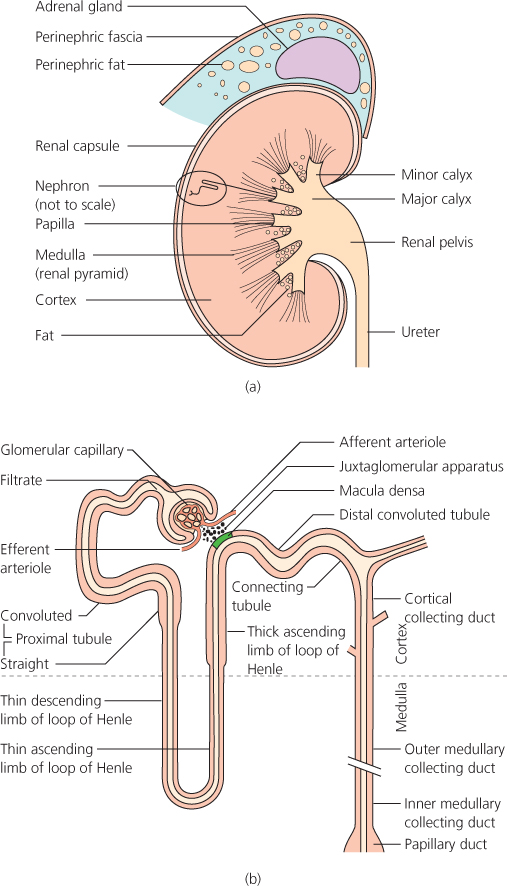

When considering renal oedema, salt and water retention and the action of diuretics, it is helpful to have in mind an understanding of both renal anatomy and physiology at the level described in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 a. Kidney structure. b. Nephron anatomy.

(Source: Adapted from The Renal System at a Glance, with permission of Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Conditions Causing Nephrotic Syndrome

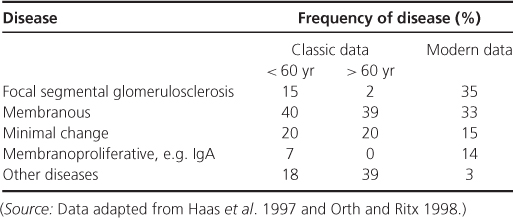

NS is caused by a wide range of conditions that can be classified as primary (idiopathic) glomerular (Table 7.1) or secondary diseases (Box 7.2).

Table 7.1 Primary glomerular diseases causing the nephrotic syndrome

- Diabetes mellitus

- Neoplasia

- Drugs

- gold

- antimicrobials

- NSAIDs

- penicillamine

- captopril

- tamoxifen

- lithium

- gold

- Infections

- HIV

- hepatitis B and C

- mycoplasma

- syphilis

- malaria

- schistosomiasis

- filariasis

- toxoplasmosis

- HIV

- SLE

- Amyloid

- Miscellaneous

Primary (Idiopathic) Glomerular Disease

Primary glomerular diseases account for the majority of cases of NS. Thirty years ago, idiopathic membranous nephropathy (see Appendix 2) was the most common primary cause. The incidence of the other glomerular pathologies, particularly focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) (see Appendix 2), has increased. There are marked racial associations with different underlying primary glomerular diseases: membranous nephropathy is the most frequent cause of NS in Caucasians, while FSGS is the cause of 50–57% of cases of NS in black patients. (Haas et al. 1997; Korbet et al. 1996).

Secondary Glomerular Disease

A wide range of diseases and drugs can cause NS. Secondary causes can often give a similar or identical histological lesion to a primary disease but have an identifiable underlying pathological process. Diabetic nephropathy is, and will remain, the commonest cause. Amyloid is also an important cause of NS; in one series AL amyloid nephropathy accounted for 10% of cases (Haas et al. 1997).

The Pathophysiological Reasons for Nephrotic Syndrome

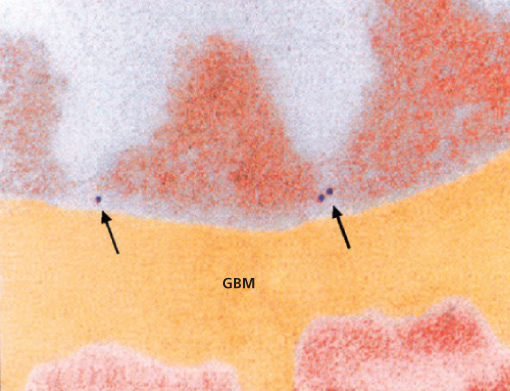

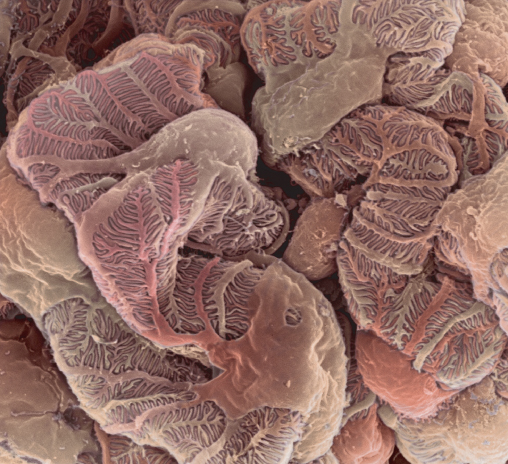

The size-selective and charge-selective filtration barrier of the glomerulus prevents the passage of proteins across it. There are three layers: the fenestrated endothelium, the glomerular basement membrane and podocytes with the slit diaphragm between their foot processes (Figures 7.2 and 7.3). NS develops from protein leakage caused by injuries to this barrier. These alter its charge and size selectivity through effects on podocytes by immune and non-immune mechanisms, and to the expression of vital adhesion molecules such as nephrin.

Figure 7.2 Glomerular slit diaphragm.

(Source: Reproduced with permission from Institute of Biotechnology, Helsinki

Figure 7.3 Electron micrograph of podocyte cells.

(Source: Reproduced with permission from Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

Explanations for Oedema in Nephrotic Syndrome

The underlying process behind sodium retention and oedema formation is complex, controversial and not fully resolved. The classic ‘underfill’ hypothesis proposes that low plasma oncotic pressure resulting from proteinuria and hypoalbuminaemia leads to intravascular volume depletion. The physiological response, via the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems, causes sodium retention and thus oedema. There are many clinical and experimental studies that tried to validate this theory; a detailed exposition is beyond the scope of this review (Deschênes et al. 2003; Koomans 2003). The alternative ‘overfill’ theory proposes that the processes causing sodium retention are intrarenal, primarily in the collecting duct of the nephron (Ichikawa et al. 1983). There are still unanswered questions and, indeed, one rather more pragmatic view is that sodium retention leading to oedema formation (Figure 7.4) is likely to result from a spectrum of pathogenic mechanisms; some ‘underfill’ and some ‘overfill’ (Hamm and Batuman, 2003).

Complications of Nephrotic Syndrome

NS has systemic consequences (Box 7.3). Not infrequently, the first manifestation of NS can be a complication, such as deep venous thrombosis (DVT), breathlessness or infection. There is overproduction of proteins in the liver (as part of the hepatic response to hypoalbuminaemia) and loss of low molecular weight proteins in the urine. Significant changes in the protein environment of the body result in many of the complications seen. It is important for the clinician to be aware of their potential and actively prevent their occurrence.

- Thromboembolism

- DVT +/− pulmonary embolism

- renal vein

- arterial (rare)

- DVT +/− pulmonary embolism

- Infection

- cellulitis

- bacterial peritonitis (rare)

- bacterial infections, e.g. pneumonia

- viral infections in the immunocompromised

- cellulitis

- Hyperlipidaemia

- Malnutrition

- Acute kidney injury

Risk of Thromboembolism

NS results in a hypercoagulable state with an increased risk of thromboembolic events. Embolism affect up to 10% of adults in clinical series of NS (Nolasco et al. 1986). Multiple abnormalities in the coagulation system occur, including increased plasma levels of pro-coagulant factors, reduced plasma levels of anticoagulant factors, abnormal platelet function, altered endothelial function and decreased fibrinolytic activity. Intravascular volume depletion, an increase in haematocrit from diuretics, and immobilization are significant contributory factors.

The most common sites of thrombosis in adults are the deep veins of the lower limb. This is often asymptomatic. Renal vein thrombosis (RVT) is a well-recognized, though uncommon, complication of NS and is said to be more common when NS is caused by membranous nephropathy or amyloidosis. Pulmonary embolism is also a potential consequence. Arterial thrombosis, affecting mesenteric, axillary, femoral, ophthalmic, renal, pulmonary and coronary arteries has also been (much more rarely) reported.

Infection

Infection can occur in up to 20% of adult patients with NS and is a significant cause of morbidity and, occasionally, mortality. Patients have an increased susceptibility to infection from low serum IgG concentrations, reduced complement activity and depression of T cell function (Ogi et al. 1994).

A variety of infectious complications, particularly bacterial, can occur. Cellulitis is common, especially in severely oedematous limbs, due to skin splits or punctures. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a serious but rare infection in adults. It can present insidiously with mild abdominal colicky pain or as fulminant sepsis. Streptococcus pneumoniae and gram-negative organisms are the most frequent causative bacteria. Viral infections have been linked to relapses in minimal change NS. Infections are a risk in patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment for NS.

Acute Kidney Injury

This is a rare complication of NS. It can happen as a consequence of excessive diuresis, interstitial nephritis related to diuretic or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, sepsis and RVT. It can happen spontaneously, usually at presentation and occurs more often in older patients. Patients can require dialysis and can take weeks to months to recover (Crew et al. 2004).

Assessing the Patient Presenting with Nephrotic Syndrome

The key aims are to assess the current clinical state of the patient, ensuring no complications are present, and to begin to formulate whether there is a primary or secondary cause underlying the syndrome. The vast majority of patients will require referral to a nephrologist for further management, including (in adults) a renal biopsy. Patients can present with complications of the syndrome with the actual diagnosis being made later (e.g. DVT).

History

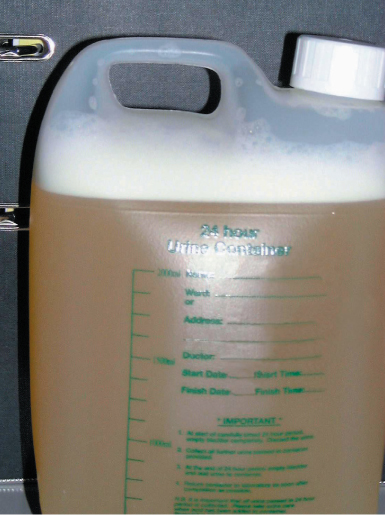

A thorough and careful history is important in elucidating the cause of NS. Patients can notice breathlessness, leg and facial swelling and, more rarely, frothy urine (protein acting like a detergent in the urine [Figure 7.5]). Particular note should be made of any features suggestive of systemic disease, for example systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), drug history (especially any recent or new medications, be they prescribed or over the counter) as well as any acute or chronic infections. It is important to remember the links with malignancy particularly of the lungs and large bowel. A history of chronic inflammation may point towards a diagnosis of secondary amyloid. A family history is also important, as there are a number of congenital causes of NS.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>