2 Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester, UK

3 Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Introduction

Irrespective of the specialty, all hospitalised patients are at risk of acute kidney injury (AKI), which is associated with high levels of morbidity and mortality. The main purpose of this chapter is to provide a guide to assist in the diagnosis, management and prevention of AKI in hospitalised patients. AKI accounts for 1% of all hospital admissions and complicates 7% of inpatient episodes. Whilst the general principles of AKI management apply to a wider population, as the incidence is highest in older people this chapter focuses on managing AKI in an ageing population and includes some of the challenges particular to this cohort of patients.

What is ‘elderly’?

This is not easy to define. When the first old age pensions were introduced by Lloyd George at the beginning of the last century, ‘elderly’ described those people who were too old to work. As the population has aged and the pension age has remained roughly the same, there is an expanding number of retired people. The proportion of retired people in the UK has increased from around 6% in 1901 to 17% (10.3 million people) today. Many of those who are in their sixties are now thought of as ‘young old’, and for the purposes of health care are not generally treated any differently from the rest of the adult population. There are, however, significant numbers of people who graduate into old age with one or more chronic conditions, and over recent years there has been an increase in those who live into extreme old age and become frail. It is predicted that the proportion of elderly people in our society will continue to grow over the next 30 years, and that this increase will be in those living into their nineties and beyond.

‘Frail’ is a term often associated with the elderly, and most people have an idea of what it means. Frailty covers a spectrum of subjective meanings and there is no generic definition that can be applied to any one individual.Measuring frailty is difficult. There are over 20 different scales which generally measure physical factors such as diminishing nutritional status, physical activity, mobility, strength and energy, psychological aspects such as deteriorating cognition and mood, and social dimensions such as lack of social contacts and social support. The main difference in managing older adults compared to younger ones is the need to take account of the degree of frailty that occurs due to the physiological changes associated with advancing age and the accumulation of disease that often accompanies it.

Physiology of ageing

Most people would be able to describe the physiology of ageing by applying common sense and everyday observations. In general terms, as we age we gradually wear out. This is true of all the bodily systems but is more apparent in some than others. As a rule of thumb, from the age of 50 we lose about 1% per year of the functioning cells of our kidneys. This does not result in a difference in effectiveness that can be detected by routine tests or patient symptoms, because the human body is equipped with an inbuilt reserve, with capacity to tolerate large demands or stresses before it begins to fail. Serum creatinine is a breakdown product of muscle creatine phosphate and is produced by the body at a constant rate and filtered out of the blood by the kidneys. Measuring serum creatinine is simple to do and is a universally accepted measure of kidney function. However, this has some limitations, not least because the rate of production of creatinine is dependent on muscle mass. As muscle mass normally diminishes with age, any concomitant deterioration in renal function may be masked, and will not necessarily be reflected by a rise in serum creatinine.

At the same time that physiological decline occurs there is an increased risk of developing significant degenerative disease. This will include conditions which have implications with respect to the kidneys, such as hypertension, diabetes and atherosclerotic disease. Not only do these conditions all have the potential to accentuate the natural decline in renal function, but the drugs used to treat them frequently have toxic effects on the kidneys. The combination of physiological ageing, accumulation of chronic conditions and the increasing burden of medications reduces the ability of older peoples’ kidneys to deal with additional stresses. It also increases their susceptibility to acute injury.

Terminology

The term acute kidney injury (AKI) has largely replaced the term acute renal failure (ARF). The change in terminology is intended to reflect the spectrum of injury that can occur with this condition and the importance of a targeted response. At the less severe end of the spectrum effective treatment may consist of increasing a patient’s oral fluid intake and adjusting their medication, whereas at the other extreme dialysis and management by the specialist team may be required. Clinically, AKI is characterised by a sudden deterioration in kidney function resulting in the body’s inability to moderate fluid balance, electrolyte and metabolic homeostasis. Although AKI is frequently reversible, prompt identification and appropriate treatment is important to reduce the risks of permanent kidney damage or death.

Acute kidney injury is increasingly common, particularly in hospitalised patients. It is associated with high levels of morbidity and mortality, with only 50% of patients surviving to six months, of whom a significant proportion remain dialysis-dependent. Although the actual incidence in the UK is unknown, an incidence of around 486 per million population has been estimated. The incidence in older people is higher because of pre-existing renal impairment and co-existing conditions, particularly vascular diseases such as diabetes and cardiac disease. Arteriosclerosis in renal blood vessels is increasingly common with advancing age, even in the absence of other comorbidities. Vascular changes lead to scarring and fibrosis of kidney tissue, which is accelerated in the presence of more generalised atherosclerosis and hypertension and leads to kidney injury. Patients with sepsis, hypotension or hypovolaemia are also at an increased risk of AKI, as are those taking medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), diuretics and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors).

AKI is a serious condition and has an associated mortality ranging between 10% and 80%. In hospitalised patients it may occur through a pre-existing or presenting condition or subsequent iatrogenic injury following admission.Patients with AKI are typically admitted for reasons other than a kidney problem and tend to be managed initially in non-specialist areas, usually by comparatively junior doctors. For this reason it is important that all those responsible for patient care can identify those at risk of AKI and initiate an appropriate response. This may include preventative measures such as rehydration, preliminary investigations, commencing treatment and referral to a more senior colleague or specialist service such as radiology or the kidney team.

Definition of acute kidney injury

AKI is characterised by a rapid fall in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and an abrupt and sustained rise in urea, electrolytes and creatinine. It can induce life-threatening fluid and electrolyte imbalances. The recent Renal Association guidelines consider the presence of one of the following scenarios as initial confirmation of AKI:

- a rise in serum creatinine ≥ 26 µmol/L within 48 hours

- a rise in serum creatinine ≥ 1.5-fold from the reference value, which is known or presumed to have occurred within one week

- reduced urine output < 0.5 mL/kg/h for more than six consecutive hours

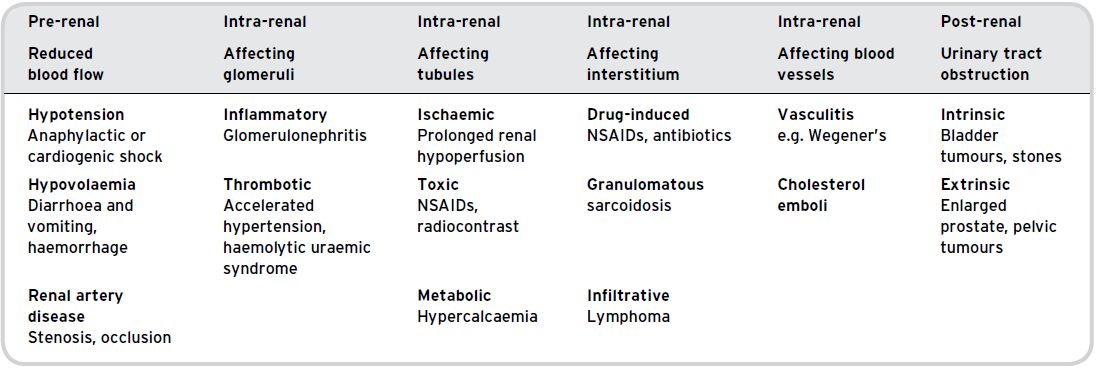

Table 6.1 The main causes of AKI.

A reference value may be available from the patient’s general practitioner and may indicate whether the rise in serum creatinine is acute or long-standing. If not available, the serum creatinine should be repeated within 24 hours.

Aetiology and outcome

The causes of AKI can be categorised into pre-renal, intra-renal (intrinsic) and post-renal causes (Table 6.1). Pre-renal causes of AKI are most commonly factors such as hypotension and hypovolaemia which cause reduced blood flow to the kidney. In patients with pre-renal AKI, prompt intervention to rehydrate and improve the patient’s blood pressure will often prevent the progression to established kidney damage, namely acute tubular necrosis (ATN).Intra-renal causes of AKI result in direct injury to the renal tissue and may involve the kidney blood vessels, tubules, interstitium or glomeruli.

The most common causes of AKI in hospitals are pre-renal: under-perfusion of the kidneys, usually due to hypovolaemia and/or relative hypotension (Table 6.2). Elderly patients are at particular risk because of the problems associated with maintaining adequate hydration in hospital and the increased likelihood of an inelastic vasculature. If left untreated, under-perfusion is likely to lead to ATN, which can last days or weeks and may result in permanent damage to the kidneys.

Approach to the patient

Many of these patients can present very unwell, and while this seems obvious it is still worth mentioning that recognising acutely unwell patients is the key to timely interventions. The generic ‘ABC’ approach to achieve some stability is always the first priority. Assuming the patient is stable and in a safe clinical environment, then the general principles of taking a history, examination, investigations and management can be implemented (Table 6.3). The initial aim is to determine whether the kidney dysfunction is due to a pre-renal, intra-renal or post-renal cause.

Physical examination

The most crucial part of the physical examination (Table 6.4) in the initial stages of management is to ensure there is no urinary retention and to correctly assess the fluid balance of the patient. While patients may present with fluid retention and oedema, many are dehydrated. It is not always possible to detect a large bladder on abdominal examination, and some form of ultrasonic imaging is mandatory. Urinary retention in females is unusual, and if it occurs careful examination of lower limb neurology is necessary to exclude spinal cord pathology.

Table 6.2 The commonest causes of hospital-acquired AKI.

| 45% of cases | Acute tubular necrosis | Secondary to acute tubular damage, often multifactorial including sepsis, hypotension and use of nephrotoxic drugs |

| 25% | Acute tubular necrosis (postoperative) | Mostly due to pre-renal causes |

| 12% | Acute contrast nephropathy | |

| In intensive care the most common cause is sepsis, usually in association with multi-organ failure | ||

Table 6.3 Clinical history.

| Pre-existing conditions | Hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, vascular disease, chronic kidney disease. Conditions affecting urinary outflow, e.g. enlarged prostate, pelvic tumour or previous stones |

| Recent acute illness | Associated with excess fluid loss, e.g. fever, diarrhoea and vomiting or reduced fluid intake |

| New medications | In particular ACE inhibitors, ARBs, antibiotics and NSAIDs. Also check over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies (see Chapter 8) |

| Symptoms that suggest systemic disease | Rashes, joint pains, myalgia, acute deafness, recurrent sinusitis or haemoptysis |

| Symptoms of advanced chronic kidney disease | Nausea, vomiting, weight loss, fatigue, itching, nocturia or hiccups |

| Family history of kidney disease | Polycystic kidneys, Alport syndrome |

In older people the commonly used signs to gauge fluid depletion can be misleading. An elevated jugular venous pressure, basal crackles and oedema can usually be safely interpreted as showing excess fluid, but it is often more difficult to determine whether the patient is dry. It is important to note here that intensely ill patients can have gross oedema at the same time as being intravascularly dehydrated. Poor skin turgor and dry mouth become an increasingly common finding in healthy older people and cannot be relied upon to indicate dehydration. More useful signs include postural hypotension, which, in the acutely unwell, is most commonly due to intravascular volume depletion. Measurement of blood pressure while the patient is supine may be falsely reassuring. If the patient is well enough to stand or even to sit upright the blood pressure in this position should also be recorded. A significant drop in postural blood pressure (> 20 mmHg in systolic pressure) may be taken as indicating significant intravascular volume depletion. Other good indicators of volume depletion include a low jugular venous pressure and a lack of axillary moisture. In a hospital environment some sweat production is normal, so if a patient’s armpit is bone-dry this is a good indicator that he or she is dehydrated. So while it is not the most pleasant place to explore, checking a patient’s armpit can be very informative. A number of tests should be performed on all patients suspected of AKI (Table 6.5), as well as urinalysis, which can indicate a number of conditions (Table 6.6).

Table 6.4 Physical examination.

| Volume status | Pulse rate, blood pressure, jugular venous pressure, dry mouth, reduced skin turgor, pulmonary crepitations (auscultation), peripheral oedema (extent of) |

| Systemic disease | Fever, splinter haemorrhages, skin rashes, joint swelling/tenderness, iritis or scleritis, new heart murmurs |

| Vascular disease | Cool peripheries, absent peripheral pulses, abdominal aortic aneurysm (palpable), vascular bruits |

| Advanced chronic kidney disease | Pallor, uraemic discoloration (yellow tinge) of the skin, excoriations, pericardial rub |

| Hypertension: long-standing or severe | Retinopathy, e.g. haemorrhages, papilloedema |

| Bladder outflow obstruction | Palpable bladder, abdominal pain |

Acute or chronic kidney disease?

Establishing whether the patient has acute or chronic kidney disease is important, because the management will differ. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) whose kidney function has worsened progressively over time (as opposed to acutely) may present with stage 5 CKD, in which any recovery of kidney function is unlikely. These patients should be referred to the specialist team for assessment and long-term management.

Previous creatinine levels

Previous creatinine levels (if available) are the most useful in determining whether or not the patient had pre-existing renal impairment. If there are a number of previous measurements taken over time it is also possible to estimate the degree of impairment and the rate of any decline. There is some controversy in the literature whether estimated GFR (eGFR) provides more clinical information regarding AKI than changes in serum creatinine (see Chapter 3).

Table 6.5 Investigations: the following tests should be performed on all patients in whom AKI is suspected.

| Full blood count | A raised white cell count may indicate an infective aetiology. Normochromic normocytic anaemia may indicate a chronic renal problem. |

| Urea and electrolytes (U&Es) | Essential for the diagnosis. Look out for rising potassium, as the treatment of this can be an emergency. Also helpful to look for previous creatinine levels to indicate whether this is acute, chronic or an acute deterioration on a background of chronic renal impairment (acute-on-chronic renal failure). |

| Glucose | New-onset diabetes can present with extreme dehydration, acidosis and renal failure. |

| C-reactive protein | This is a good indicator of an ongoing inflammatory or infective process. Can also be used to monitor response to therapy. |

| Calcium | High calcium levels can cause an osmotic diuresis and subsequent dehydration and renal failure, but lower levels may point to a more chronic renal problem – often associated with a high serum phosphate. |

| Blood gases | These are particularly useful in determining the acid–base balance and can indicate the extent of any acidosis, which may be life threatening. |

| Chest x-ray | Looking for signs of fluid overload or infection. |

| Renal tract ultrasound | This will reliably determine whether there is any obstruction to the renal system. This is essential and should be done as an emergency, as any obstruction will require immediate treatment. |

| Antibodies | Assays for autoimmune diseases which can affect the kidneys should be requested when there are signs or symptoms of systemic disease. ANCA, ANA, anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibody can usually be done urgently but need liaison with your local immunology laboratory. |

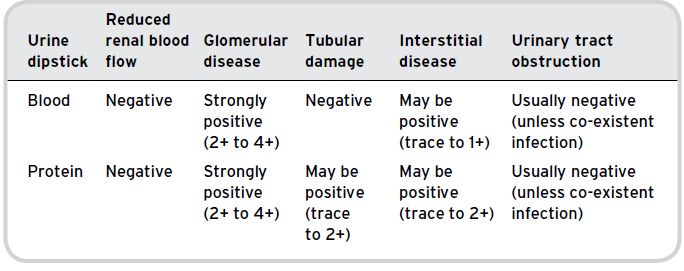

| Urine | The urine should be collected and tested on the ward with a routine dipstick analysis. This will give an indication of the presence of protein, blood, leucocytes and nitrites. Positive nitrites and leucocytes would support a diagnosis of infection. Blood and protein can be helpful when considering causes of intra-renal kidney disease. |

Table 6.6 Urinalysis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree