- The term acute kidney injury (AKI) is now preferred in kidney circles to the older term acute renal failure (ARF).

- The life-threatening consequences of AKI are volume overload, hyperkalaemia and metabolic acidosis.

- AKI is more common in older patients and those with underlying chronic kidney disease (CKD).

- Precipitating factors include hypovolaemia and hypotension (pre-renal); the use of nephrotoxic drugs and radiographic contrast (intrinsic renal); and obstruction from e.g. stones, malignancy or retroperitoneal fibrosis (post-renal).

- Prevention strategies include maintaining adequate blood pressure (BP), ensuring adequate volume status and avoiding potentially nephrotoxic drugs.

- AKI is frequently reversible, and rapid recognition and treatment may prevent irreversible nephron loss.

- If past creatinine measurements are not available, useful differentiating features of acute (as opposed to chronic) renal failure may be the absence of anaemia, hypocalcaemia, hyperphosphataemia and/or reduced renal size and cortical thickness, which often accompany CKD.

- Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is the commonest cause of intrinsic renal disease, and if the precipitating factor has been removed or treated, prognosis is generally good. However, other causes must always be excluded as they have important management implications:

- rashes, arthralgia or myalgia may suggest an underlying multisystem disease;

- antibiotics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs NSAIDs may cause interstitial nephritis;

- non-visible haematuria or proteinuria, or dysmorphic red cells or red cell casts, may suggest renal inflammation such as glomerulonephritis or acute interstitial nephritis.

- rashes, arthralgia or myalgia may suggest an underlying multisystem disease;

Definition and Classification

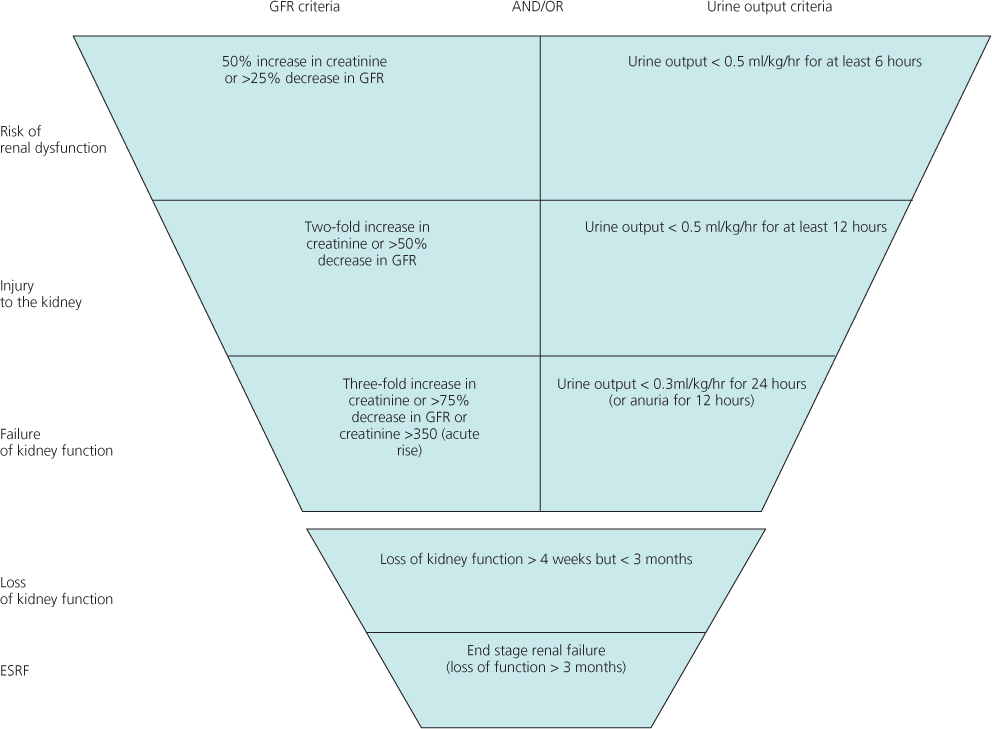

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is characterized in an abrupt fall in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), clinically manifest as an abrupt and sustained rise in urea and creatinine. Potentially life threatening consequences include volume overload, hyperkalaemia and metabolic acidosis. The RIFLE criteria classify AKI according to degree and outcome (Figure 2.1). A revised definition of AKI based upon modifications to the RIFLE and Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) criteria has been made by the KDIGO clinical practice guidelines (Table 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Acute kidney injury classified according to degree and outcome by RIFLE criteria. RIFLE defines three degrees of increasing severity of AKI (risk, injury and failure) and two possible outcomes (loss and ESRF).

Table 2.1 AKI classified according to serum creatinine and urine output criteria. The diagnostic criteria for AKI are an abrupt (within 48 hours) absolute increase in the serum creatinine concentration of ≥0.3 mg/dL (26.4 µmol/L) from baseline, a percentage increase in the serum creatinine concentration of ≥50%, or oliguria of less than 0.5 mL/kg per hour for more than six hours

| Stage | Serum creatinine criteria | Urine output criteria |

| 1 | Increase in serum creatinine of more than or equal to 0.3 mg/dL (≥26.4 µmol/L) or increase to more than or equal to 150 to 200% (1.5- to 2-fold) from baseline | Less than 0.5 mL/kg per hour for more than 6 hours |

| 2 | Increase in serum creatinine to more than 200 to 300% (> 2- to 3-fold) from baseline | Less than 0.5 mL/kg per hour for more than 12 hours |

| 3 | Increase in serum creatinine to more than 300% (> 3-fold) from baseline (or serum creatinine of more than or equal to 4.0 mg/dL [≥354 µmol/L] with an acute increase of at least 0.5 mg/dL [44 µmol/L]) | Less than 0.3 mL/kg per hour for 24 hours or anuria for 12 hours |

Epidemiology

AKI is increasingly common: this probably reflects true increased incidence, and better detection. Recent data suggest an incidence of AKI, defined as serum creatinine above 500 µmol/L, of around 500 per million population (pmp) per year, which is twice the UK prevalence of haemodialysis patients and therefore places high demands upon healthcare resources. AKI is more common with increasing age, the highest incidence being in the 80- to 89-year-old age group (950 pmp/year).

AKI (as per KDIGO criteria) complicates at least 20% of emergency hospital admissions, mostly in patients with underlying chronic kidney disease (CKD), and is generally multifactorial in nature chiefly associated with hypovolaemia, hypotension and the use of nephrotoxic drugs or radiographic contrast. When severe enough to require dialysis, in-hospital mortality is around 50%, and may exceed 75% in the context of sepsis or in the critically ill.

Aetiology

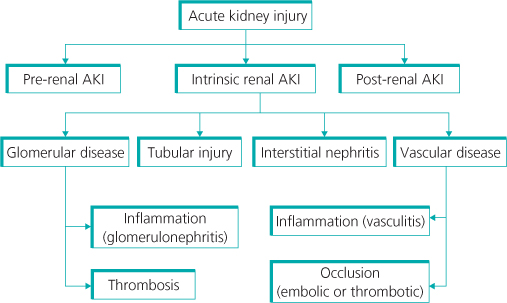

The causes of AKI can be grouped into three major categories (Figure 2.2):

- decreased renal blood flow (pre-renal; 40–80% of cases);

- direct renal parenchymal damage (intrinsic renal; 35–40% of cases);

- obstructed urine flow (post-renal or obstructive; 2–10% of cases).

Pre-renal Acute Kidney Injury

Renal blood flow (RBF) and GFR remain roughly constant over a wide range of mean arterial pressures owing to changes in afferent (pre-glomerular) and efferent (post-glomerular) arteriolar resistance. Below 70 mmHg, autoregulation is impaired and GFR falls proportionately. Renal autoregulation chiefly depends on a combination of afferent arteriolar vasodilatation mediated by prostaglandins and nitric oxide, and efferent arteriolar vasoconstriction mediated by angiotensin II. Drugs that interfere with these mediators may provoke pre-renal AKI (Table 2.2) in certain settings. With renal artery stenosis or volume depletion, GFR maintenance is particularly angiotensin II-dependent. Use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor antagonists can induce AKI. With volume depletion, angiotensin II and noradrenaline levels are generally high, and in this setting NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) or cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors, which inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, permit unopposed action of local vasoconstrictors on both afferent and efferent arterioles, leading to an acute decline in GFR.

Intrinsic Renal Acute Kidney Injury

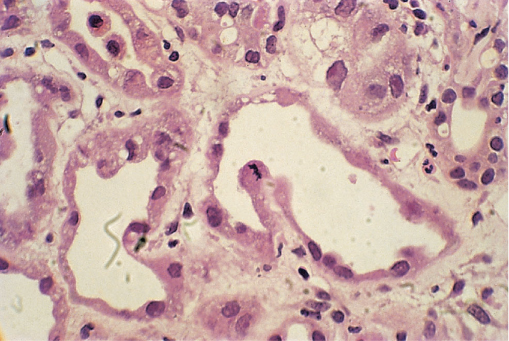

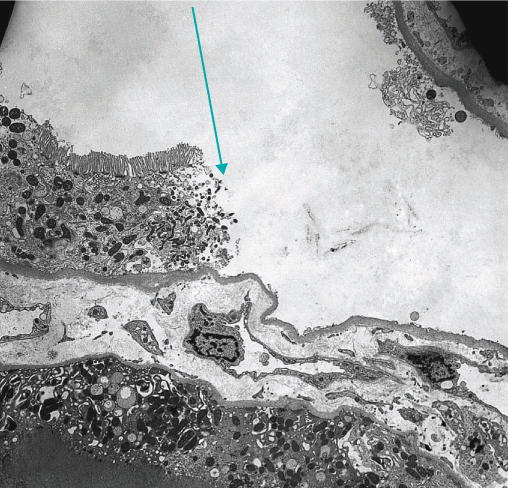

Parenchymal causes of AKI may be subdivided into those primarily affecting the glomeruli, the tubules, the intrarenal vasculature or the renal interstitium. Overall, the commonest cause is acute tubular necrosis (ATN) (Figures 2.3 and 2.4), resulting from continuation of the same pathophysiological processes that lead to pre-renal hypoperfusion. In intensive care, the commonest cause is sepsis, frequently accompanied by multi-organ failure. Post-operative ATN accounts for up to 25% of cases of hospital-acquired AKI, mostly due to pre-renal causes. The third commonest cause of hospital-acquired AKI is acute radiocontrast nephropathy. See also Table 2.3.

Figure 2.3 A histological view of renal tubular dilatation and loss of renal tubular epithelial cells in acute kidney injury (‘acute tubular necrosis’).

Figure 2.4 Electron micrograph of disrupted renal tubular epithelium in acute tubular necrosis. The arrow points to the segment where the delicate microvillous tubular epithelial lining is lost.

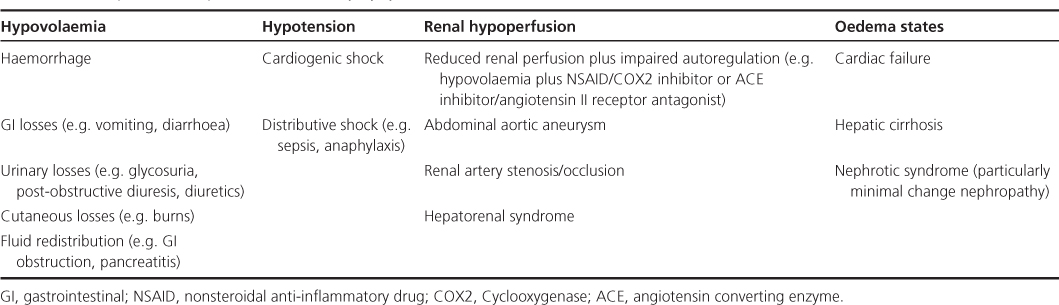

Table 2.2 Principal causes of pre-renal acute kidney injury