| 13 | Acute and Chronic Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

Definitions

Definitions

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding is defined as acute or chronic blood loss from a source distal to the ligament of Treitz. The following sections will focus on bleeding from sources in the colon and anal canal.

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding is defined (rather arbitrarily) as a bleeding situation in which blood loss has been occurring for less than three days and is causing hemodynamic instability, anemia, or the need for a blood transfusion.

Chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding. The definition of chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding is rather broad, encompassing longstanding or intermittent blood loss of smaller amounts of blood through rectum or melena, but also fecal occult blood loss (often not discovered until the patient seeks medical attention for anemia).

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Incidence of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding is reported in the literature at 20-27 per 100 000 per year (20). A recent study from the Netherlands has reported lower figures (8.9 per 100000 per year) (33). Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding occurs less frequently than acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (100-200 per 100000 per year). The small intestine is the bleeding site in only 0.7-9 % of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding (63).

Current symptoms |

|

Medical history |

|

History of drug therapy |

|

Prognosis and Clinical Course

Prognosis and Clinical Course

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Spontaneous cessation of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding occurs in ca. 80% of patients (63). The mortality rate among patients hospitalized with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding is 2.4%; if bleeding occurs during hospital stay, the rate increases dramatically to 23.1 % (34). A more recent study on patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding found six predictive factors which increase the likelihood of severe course or recurrence of bleeding: tachycardia above 100/min, systolic blood pressure below 115 mmHg, syncope, loss of tenderness to pressure on the abdomen, blood loss in the first four hours after hospitalization, and acetylsalicylic acid use (51).

Chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding. The prognosis for patients with chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding depends primarily on the bleeding source. Among older patients with iron-deficiency anemia, the most frequent cause of bleeding is a colon carcinoma. Further prognosis is determined by the carcinoma.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Medical history. Patient medical history can supply valuable information for diagnosing lower gastrointestinal bleeding (Tab. 13.1). Stool color is very important: If the patient’s vital signs are stable, loss of larger amounts of fresh blood (hematochezia) indicates with high probability that the bleeding site is the colon the while “tarry stool” (melena) indicates a site higher in the gastrointestinal tract.

Physical examination. Physical examination should focus first on the patient’s vital signs, e.g., pulse and blood pressure. Marked tachycardia accompanied by a drop in blood pressure, tachypnea, and drowsiness is a sign of blood loss of more than 1500 mL. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding causes anemia or faintness/dizziness in more than half of all patients, though its course is less dramatic than upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Aspiration of gastric contents and laboratory tests. Aspiration of stomach contents using a nasogastric tube has a high predictive value with regard to bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz, though it cannot exclude it with total certainty in the negative case. Hemoglobin count can provide information on the severity of bleeding. In actual practice, the creatine kinase (CK) urea ratio, which has been recommended for differentiating between upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding, is not of great assistance for diagnosis in actual bleeding situations (39).

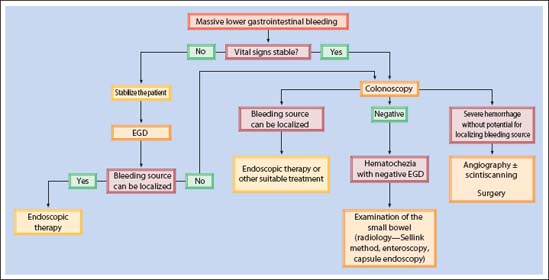

Fig. 13.1 Algorithm for diagnosis and therapy in acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding with hematochezia.

Endoscopic Diagnosis

Endoscopic Diagnosis

Chronic Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding in patients over 50 years of age is most frequently caused by a neoplasia in the colon. Regardless of whether rectal examination and rectoscopy/proctoscopy play a role in initial diagnosis, total colonoscopy is essential for further diagnosis. This applies to patients who have unexplained iron-deficiency anemia as well as those with positive fecal occult blood tests. Results have clearly shown that colorectal carcinoma mortality can be reduced by consistent use of colonoscopy in patients with positive fecal occult blood tests. Compared with diagnosing adenomas or carcinomas, other diagnoses (e.g., chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, angiodysplasia, and damage from radiation therapy) play a lesser role. If no pathology is found during colonoscopy in a patient with occult gastrointestinal bleeding or anemia, endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract is indicated. According to a study by Zuckerman and Benitez, the upper gastrointestinal tract more often causes occult blood loss than does the lower gastrointestinal tract (62). If the upper gastrointestinal tract (to the ligament of Treitz) also fails to yield any useful findings, the small intestine must be examined.

Intermittent melena. Intermittent melena (“tarry stool”) is an indication for gastroesophageal duodenoscopy as it is highly likely that the lesion can be found in the area examined. If there are no findings, the procedure is the same as for occult gastrointestinal bleeding, i. e., small and large bowel are investigated.

Bleeding into the rectum. Chronic or intermittent loss of smaller amounts of fresh blood is typical for a bleeding source in the colon. In the majority of patients, the source is a lesion in the anal canal or a distal colon segment. Patient medical history is useful for diagnosing lesions in the anal canal. If the patient is over 50 years of age, total colonoscopy should be attempted regardless. Colonoscopy is not necessary in younger patients with a bleeding source in the anal canal (3).

Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Severity of bleeding. Procedures for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding depend on whether bleeding is moderate or heavy. Severity of bleeding is determined by amount of blood being lost and also by the stability of the patient’s vital signs. If bleeding is heavy, stabilizing the patient and replacing lost blood have priority over diagnosis. Figure 13.1 summarizes the diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Excluding upper gastrointestinal bleeding. In up to 11 % of all patients with rectal bleeding in whom lower gastrointestinal bleeding is initially suspected, the bleeding source turns out to be located in the upper gastrointestinal tract (31, 38). Potential upper gastrointestinal bleeding sources must especially be considered among patients presenting with hematochezia and unstable vital signs.

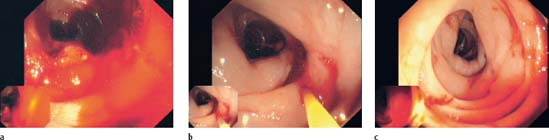

Fig. 13.2 Bleeding diverticulum.

a Acute diverticular bleeding.

b An epinephrine solution (1:10000) is injected into the edge of the diverticulum (hidden by a fold).

c Cessation of bleeding after injection; edematous swelling of the mucosa where the epinephrine was injected.

Fig. 13.3 Bleeding from a small diverticulum.

a Bleeding from a small diverticulum, barely recognizable by a streak of red blood.

b Cessation of bleeding after application of two hemoclips (Olympus), closing the diverticular orifice.

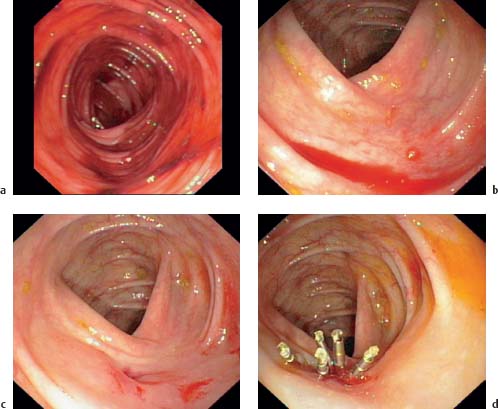

Fig. 13.4 Diverticular bleeding.

a Colonic mucosa covered with fresh blood.

b A sea of blood visible behind a fold after irrigation.

c After further irrigation and suction a diverticulum is visible with a slightly eroded mucosa near the orifice.

d Several hemoclips (Olympus) are applied to the suspected bleeding source.

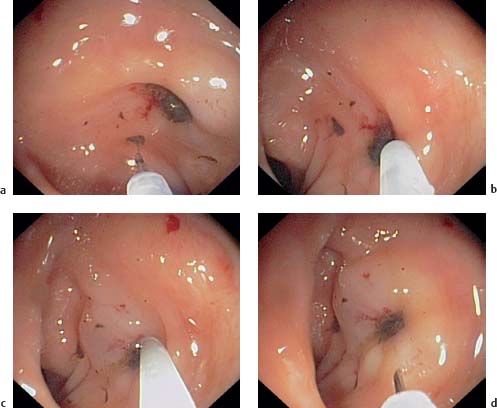

Fig. 13.5 Visible vessel in a diverticular orifice.

a Visible vessel protruding from a small diverticular orifice making it unrecognizable.

b Visible vessel is closed mechanically using a hemoclip (Olympus).

Fig. 13.6 Visible vessel protruding from a diverticulum. Edematous swelling of the mucosa on the edge of the orifice.

Fig. 13.7 Visible vessel on the base of a diverticulum.

Fig. 13.8 Visible vessel.

a Visible vessel, protruding near the edge of a small diverticulum.

b Closed with a hemoclip (Olympus).

Fig. 13.9 Adherent clot on a diverticular orifice. An open diverticular orifice is visible next to this one.

Fig. 13.10 Clot, inside a diverticulum, but not adherent. Unlike an adherent clot (Fig. 13.9), it can be easily washed off.

Fig. 13.11 Blood clot on a diverticulum.

a Adherent clot on a diverticulum, not removable with irrigation.

b, c Needle injection of epinephrine (1:10000) into the wall of the diverticular orifice.

d The orifice is swollen afterward and the mucosa is whitish in color from the vaso-constrictive effect of the epinephrine. The clot was subsequently removed by irrigation.

Bleeding site | Frequency in % |

|---|---|

Rectum | 15.1 |

Sigmoid colon | 15.1 |

Descending colon | 19.7 |

Transverse colon | 12.7 |

Ascending colon | 15.1 |

Cecum | 2.6 |

Terminal ileum | 1.7 |

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Diverticula

Diverticula are the reported source of gastrointestinal bleeding in 17-40% of patients (Tab. 13.4). An estimated 3-5% patients with colonic diverticula experience bleeding once in their lifetime. However, the correlation may not always be causal since diverticula are often cited as the bleeding source in the colon for lack of evidence of another source.

These excellent results are contradicted, however, by another current study (8) in which a retrospective analysis of diverticular bleeding was conducted. Using the same endoscopic intervention measures, this study found earlier rebleeding in 38 % of patients and late rebleeding in 23%. At first glance, the results of these two studies appear contradictory. Yet, a closer look reveals that Jensen et al. (30) consistently advise their patients to discontinue use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetylsalicylic acid and to follow a high-fiber diet. It is therefore entirely possible that these additional factors help explain differing results and that nonendoscopic factors also play an important role in treatment outcome.

Diagnosis | Noninten-sive-care unit patients (n = 77) | Intensivecare unit patients (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|

Diverticula | 38% | 17% |

Ischemic colitis | 13% | 50% |

Angiodysplasia | 6% | 8% |

Postpolypectomy rebleeding | 6% | – |

Rectal ulcer | 5% | 8% |

NSAID colitis | 5% | 8% |

Carcinoma | 4% | – |

Misc. | 22% | 1% |

Source of hematochezia | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

Diverticula | 17-40 |

Arteriovenous malformation | 2-30 |

Colitis (ischemic, infectious, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, radiation colitis) | 9-21 |

Neoplasias, postpolypectomy bleeding | 11-14 |

Anorectal sources (incl. hemorrhoids, rectal varices) | 4-10 |

Upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding (incl. ulcers, varices) | 0-11 |

Small bowel (incl. Crohn disease, arteriovenous malformation, Meckel diverticula, tumors) | 2-9 |

Definite criteria for a bleeding source in the large intestine in urgent colonoscopy |

|---|

|

Stigmata of bleeding in the colon or in a particular colon segment |

|

Endoscopic therapy methods. There is no consensus on which therapeutic measure offers the most optimal treatment for diverticular bleeding. Systematic comparative studies are lacking and publications on the principles of endoscopic therapy tend to have a casuistic character. Studies have reported on the success of injection therapy (Figs. 13.2, 13.11) using epinephrine and fibrin glue, as well as thermocoagulation by means of laser, heater probes, and bipolar coagulation. An interesting report has also been written on mechanical hemostasis of diverticular bleeding using hemoclips (27) (Figs. 13.4, 13.5,13.8).

Fig. 13.12 Oval erosion (arrow) with fibrinous exudate on the edge of a diverticulum, protruding into the diverticulum neck.

Fig. 13.13 Small, round, erosion with fibrinous exudate

on the base (“dome”) of a diverticulum.

In the midst of the discussion on optimal endoscopic treatment of diverticular bleeding, one should keep in mind that spontaneous cessation of bleeding occurs in over two-thirds of diverticular bleeding cases and that rebleeding occurs frequently in the course of disease. In one study (34) the risk of rebleeding was 9 % in the first year, 10 % in the second year, 19 % in the third year, and 25 % in the fourth year.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

A recent study identified colon diverticula as the bleeding source in 22% of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding, whether based on active bleeding (

A recent study identified colon diverticula as the bleeding source in 22% of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding, whether based on active bleeding (