2 General Practitioner, Birmingham, UK

Introduction

In the past, kidney medicine was regarded as rare, complicated and best left to the specialists. Now it is an everyday part of primary care. This chapter demystifies chronic kidney disease. It uses real-life examples and gives practical suggestions for treating patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) from stages 1 to 5. Citing recent trial evidence, it signposts you to information and educational resources for clinicians and patients.

Joined-up working – the key to success

Good primary care, working in collaboration with secondary care, is crucial for the successful management of all stages of CKD (defined below). To confirm CKD, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) must be measured on two or more occasions at least three months apart. Most patients with CKD are at stage 3 and can be managed effectively in the community. Specialist care is more often needed for stages 4 and 5 (Table 3.1).

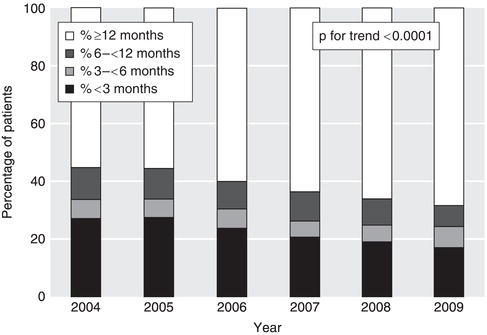

CKD that has worsened over years can suddenly decompensate to cause acute problems such as pulmonary oedema. If you identify such patients early, you will reduce the chances of an emergency hospital admission. Following an unplanned start of dialysis, mortality in the first year is doubled and time spent in hospital tripled compared to a planned start. Thanks to improved collaborative working, the proportion of patients starting dialysis without adequate pre-dialysis nephrology care has fallen steadily in the UK (Figure 3.1).

Text not available in this digital edition.

Figure 3.1 The lengths of time patients were known to a kidney unit before the start of renal replacement therapy (RRT), as a percentage of all patients starting. Data are from 11 English kidney units that have reported data continuously since 2004 with > 75% data completeness. 6730 patients started RRT in the UK in 2009. (2010 Report, Nephron Clinical Practice Vol. 119, Suppl. 2, 2011, UK Renal Registry 2010, 13th Annual Report of the Renal Association, Caskey F, Dawnay A, Farrington K, Feest T, Fogarty D, Inward C, Tomson CRV, UK Renal Registry, Bristol, UK. The data reported here have been supplied by the UK Renal Registry of the Renal Association. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the UK Renal Registry or the Renal Association).

Should I screen for CKD?

Screening of the well population for albuminuria or eGFR is not cost-effective, nor clinically appropriate. On the other hand, targeted screening is worthwhile. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends that you offer testing for CKD, i.e. blood for eGFR and urine for albumin : creatinine ratio (ACR), to people who have:

- diabetes, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease or cerebrovascular disease

- structural urinary tract disease, kidney stones or an enlarged prostate

- a multisystem disease with potential kidney involvement (for example, systemic lupus erythematosus)

- a family history of stage 5 CKD or hereditary kidney disease

- blood or protein detected on urinalysis

Test for microscopic haematuria with reagent strips; there is no need to use urine microscopy to confirm a positive result. Confirm results of 1+ or more by a positive result on two out of three repeat tests. Investigate for urinary tract malignancy in appropriate patients, such as those aged over 50 years. Macroscopic haematuria always requires an explanation, whatever the age of the patient.

Patients with persistent microscopic haematuria who do not have proteinuria or a known urological cause are still at an increased risk of hypertension, proteinuria and reduced GFR in the future. They should be followed up annually with repeat testing for haematuria and proteinuria on urinalysis, GFR and blood pressure, as long as the haematuria persists.

NICE recommends that people receiving long-term lithium have their eGFR checked at least every six months, and those taking systemic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) at least annually.

Should I tell patients they have CKD?

The term ‘chronic kidney disease’ includes two words that mean different things to patients and clinicians. To lay people, ’chronic’ implies severe, serious, and possibly cancer; and ‘disease’ relates to feeling ill. None of these applies to the early stages of CKD, and it is important not to raise unnecessary alarm. However, no one wants to miss the opportunity of avoiding severe illness in the future.

When explaining CKD, you may find it helpful to use an everyday analogy – money. ‘At birth, your two kidneys normally have enough kidney function to last your whole life. This is like having a lot of money in your kidney savings account. As you get older, your kidney function slowly goes down and your savings are used up. If you do not have normal kidneys to start with, or they lose function more quickly than normal, you will run out of “savings” and start to feel ill.’

How do I identify patients who are likely to be troubled by their kidney disease?

Simple urinalysis is the first step. The greater the amount of proteinuria or albuminuria, the greater is the risk that GFR will decline in future. Conversely, the absence of albuminuria in a patient with CKD is a good prognostic sign.

Patients who suffer one or more episodes of acute kidney injury (AKI, previously termed acute renal failure) have an increased risk of advanced CKD and death in the long term, even if their GFR recovers following the acute episode. Highlight this past medical history in the patient’s records.

Younger patients with kidney disease, such as damage due to reflux in childhood, are at a high lifetime risk of progressing to advanced CKD. They may develop proteinuria and hypertension before the decline in eGFR. Similarly, patients under the age of 40 years with idiopathic hypertension are at a higher risk, especially if they have proteinuria.

You should counsel younger women with CKD or proteinuria about their increased risk of complications during pregnancy. The lower the eGFR, the more likely they are to have pre-eclampsia, premature delivery and neonatal complications. In turn, the increased kidney blood flow in pregnancy can accelerate the decline in GFR. Advise women about contraception and consider referring them to an obstetrician or nephrologist when they are planning a pregnancy.

Which patients should I refer to a nephrologist?

Patients without diabetes mellitus who have more than 1 g per day of proteinuria (urine albumin : creatinine ratio (ACR) > 70 mg/mmol or protein : creatinine ratio > 100 mg/mmol) are likely to have a significant glomerular disease. You should refer them for consideration of a renal biopsy.

In patients with diabetes, these levels of proteinuria put them at very high risk of progressive loss of GFR. They too should be referred to a nephrologist to make sure everything is being done to reduce this risk.

Patients with both haematuria and proteinuria (urine ACR > 30 mg/mmol with dipstick haematuria) who do not have symptoms of urinary tract infection may have glomerulonephritis. This may be a kidney-limited disease with no other symptoms, or it may be part of a systemic disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or vasculitis. A vasculitic illness may include low-grade fever, tiredness, weight loss, joint pains, rash and ENT symptoms. GFR may decline rapidly, so repeat the eGFR measurement a week after the first detection. Discuss the details with a nephrologist at an early stage. By getting treatment started quickly, you may avoid the need for long-term dialysis.

Patients with poorly controlled blood pressure (> 150/90 mmHg) have a higher risk of kidney failure and death. You may need specialist advice in a minority of patients whose blood pressure is not controlled even though they take the medication regularly.

Older men with reduced eGFR and symptoms such as frequency, dribbling and nocturia may have chronic urinary retention and hydronephrosis. These men may be unaware of the severity of the problem, assuming the symptoms are a sign of old age. If you find suprapubic dullness and a palpable bladder you should make an urgent hospital referral. Otherwise request an ultrasound scan to be performed within four weeks.

Patients with stage 4 CKD who are not unwell and whose eGFR is not deteriorating may not need to attend an outpatient appointment. However, it is a good idea to get the advice of your local nephrologist to make sure nothing important is being overlooked. Conversely, patients with stage 5 CKD should be reviewed in person by a nephrologist so that a long-term treatment plan can be discussed, unless they are too unwell or unwilling to travel to the clinic (see Chapter 10).

You may be asked to monitor patients with uncommon causes of CKD as part of a disease-specific management plan. This should include clear criteria for when to seek advice from the nephrologist. All patients with CKD should take an active part in their care plan, monitoring their own blood pressure and keeping track of their eGFR. Patients can access their own blood results securely via the internet using Renal PatientView (www.renalpatientview.org). Patients with rare kidney diseases may wish to join a self-help group linked to Rare Disease UK (www.raredisease.org.uk).

Monitoring kidney function – the power of the eGFR graph

Having identified who is at risk of kidney failure, you and the patient need a simple and effective tool for monitoring kidney function. This is the eGFR graph.

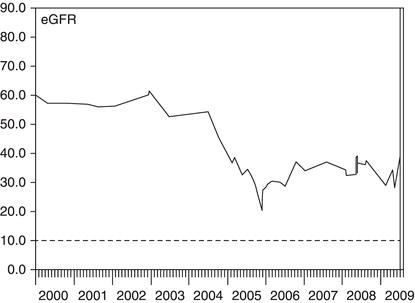

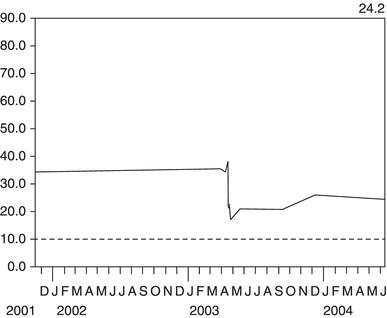

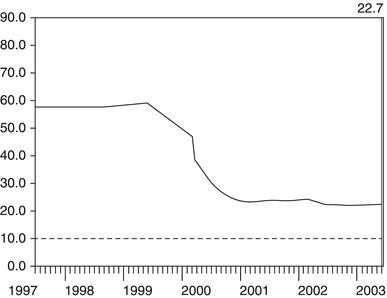

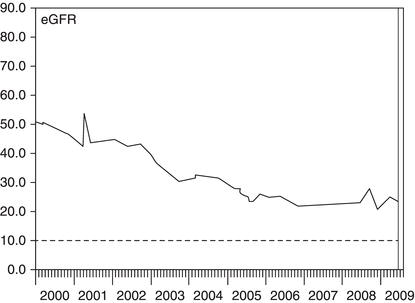

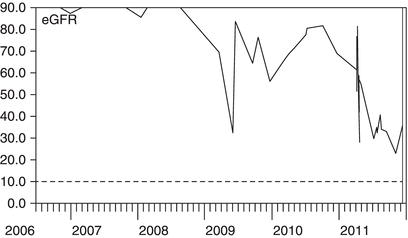

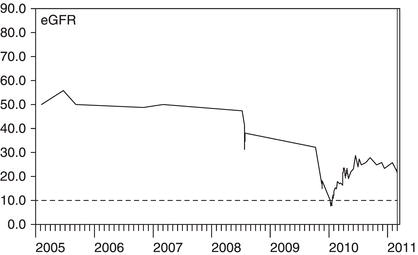

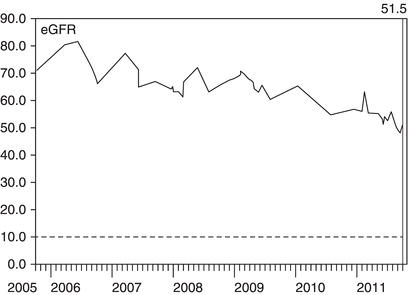

Symptoms are of no help in tracking the early stages of CKD. Instead, the eGFR graph acts as a map of the kidney history. The examples shown in Figures 3.2–3.7 demonstrate its value in describing the natural history of kidney disease. See if you can work out from the graphs when the management could have been better.

Figure 3.2 This man was referred to a nephrologist in late 2005 because of a progressive decline in eGFR. He had diabetes and was feeling more tired but did not volunteer any new symptoms. On examination, he had a prominently distended bladder. eGFR improved following catheterisation to relieve his chronic urinary retention and bilateral hydronephrosis, but sadly not to its previous level.

Figure 3.3 This woman had diabetes and macroscopic haematuria. An ultrasound scan revealed a renal cell carcinoma that was removed in April 2003. After the operation, her eGFR fell by 50% but then recovered slightly as some nephrons increased their filtration rate to compensate for the loss of one kidney.

Figure 3.4 This man had peripheral vascular disease. An ultrasound scan in 2001 showed a small left kidney that had become ischaemic over the preceding two years, leading to a decline in the combined GFR of both kidneys.

Making sense of variation in eGFR

NICE guidance suggests that a decline in eGFR of > 5 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year or > 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 within five years should prompt a search for remediable causes. These numerical rules are hard to apply when the eGFR is varying month by month. The eGFR graph makes it easy to see whether a drop is part of a consistent downward trend, as in the example shown in Figure 3.8.

Figure 3.5 This lady had diabetes and poorly controlled blood pressure despite taking an ACE inhibitor. At her first consultation with a nephrologist in 2005, she was shown her eGFR graph and encouraged to measure her own blood pressure at home, with a target systolic pressure of less than 140 mmHg. A diuretic was added to the ACE inhibitor. Following control of her blood pressure, the decline in her eGFR was arrested.

Figure 3.6 This woman had diabetes and normal kidney function until she suffered a myocardial infarction (MI) in 2009. This was complicated by acute kidney injury (AKI), which only partially resolved. In 2011 she suffered a second MI, again complicated by AKI. She was left with moderate to severe CKD and at risk of needing dialysis in the future.

Judge the most recent result against the previous range of variation in eGFR for that patient. Variation is greatest when the eGFR is > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. eGFR values at this level are calculated from near-normal levels of serum creatinine. Variation at lower levels of serum creatinine leads to large variation in the eGFR because the two are inversely related. Conversely, variations in eGFR below 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 are more likely to represent important changes in GFR.

Figure 3.7 This man had type 1 diabetes and his eGFR was slowly declining. In late 2009, his eGFR dropped much more rapidly and urinalysis was positive for blood and protein. A kidney biopsy showed crescentic glomerulonephritis. His GFR responded well to high-dose steroids and cyclophosphamide.

Figure 3.8 This man suffered with bipolar disorder and was taking long-term lithium therapy. Lithium can cause both reversible changes in fluid balance and irreversible damage to renal tubules. Reviewing the results over six years makes the declining trend due to irreversible damage obvious.

Misleading estimates of GFR

Estimated GFR (eGFR) is calculated from the serum creatinine concentration. Changes in the serum creatinine concentration may not always be due to changes in the true GFR.

Variation in the laboratory creatinine assay is proportionally greatest in or near the normal range. Hence most laboratories do not report an exact figure for eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 because the confidence interval at this level is so wide.

Changes in meat intake can lead to small short-term changes in the serum creatinine concentration. However, you do not usually need to ask the patient to starve before the blood test.

Body builders and athletes have a large muscle mass. This produces a lot of creatinine, increases the serum creatinine level and gives a misleadingly low eGFR. In addition, some take dietary protein and creatine supplements. These are digested to release urea and creatinine into the bloodstream and so further reduce the estimated GFR. To give a more consistent estimate of GFR, take blood samples after a week without supplements.

Take care to use the eGFR correction factor for African-Caribbean race where appropriate – this increases the estimate by 21%.

Some drugs can alter the serum creatinine level without affecting the true GFR. Trimethoprim inhibits the secretion of creatinine by the kidney tubules, leading to a rise in serum creatinine concentration. Fibrates can alter muscle creatinine metabolism and increase serum creatinine. As the true GFR is unaltered, these effects do not alter the serum urea – a helpful pointer to this explanation.

Finally, if a change in eGFR seems inexplicable, check whether the patient’s gender has changed between male and female, either surgically or inadvertently on the blood test request form.

If you suspect that a persistently reduced eGFR may not reflect the true GFR, check for other signs of kidney disease such as proteinuria, hypertension and abnormalities on ultrasound.

What does proteinuria mean?

Proteinuria results from damage to the endothelial cells and basement membranes of the glomeruli. It is also a sign of damage to the vascular endothelium elsewhere in the body. Hence, proteinuria is an important risk marker for future worsening of kidney function and for cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and stroke. The greater the amount of proteinuria, the greater is the risk of loss of GFR and the faster it is likely to decline.

Day-to-day variation in the amount of proteinuria can be large, 100% or more, due to the effects of exercise, diet and blood pressure. However, longer-term trends in the amount of proteinuria are useful guides to changes in the risk of kidney damage. In patients with CKD and high blood pressure, a sustained reduction in proteinuria is an encouraging sign that improved control of blood pressure is giving long-term benefits.

The strength of the correlation between proteinuria and the risk of kidney failure has led to it being used as a surrogate outcome in drug trials of patients with CKD. Unfortunately, not all ways of reducing proteinuria also reduce the risk of kidney failure. Combining drugs that inhibit the renin–angiotensin system (such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and renin inhibitors) reduces proteinuria, but longer-term trials have shown an increase in the risk of kidney failure in some patients.

Proteinuria is a guide to the long-term risk of kidney and cardiovascular disease, so there is little value in measuring it repeatedly in elderly patients with limited life expectancy.

Management of patients with CKD

Your two main roles in the management of patients with kidney disease are: (1) to minimise the cardiovascular risk associated with CKD, and (2) to reduce the rate of loss of kidney function. The actions required for both are similar. Complex management of kidney diseases, such as with immunosuppressive drugs, should remain in secondary care.

The CKD Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) encourages practices to develop a CKD register of patients with stage 3–5 disease, record blood pressure and urine ACR measurements at least annually, control blood pressure (target < 140/85) and use angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients with proteinuria. You may wish to expand your QOF CKD register to include patients with abnormal kidneys or albuminuria and eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Most patients with CKD are on at least one other chronic disease register, such as diabetes, coronary heart disease or hypertension. You may wish to operate a combined vascular disease clinic to avoid duplication of effort. Organise primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease according to the usual guidelines. Most patients will need to be reviewed every 6–12 months depending on their clinical need.

Get the results of tests for serum urea and electrolytes, eGFR, corrected calcium, phosphate, HbA1c if diabetic, lipids, full blood count, and urine ACR (preferably an early-morning sample) and share them with the patient a week or two before the clinical review. During the face-to-face consultation, discuss the test results and home blood pressure readings, and agree goals for the future. Carry out a general health check, and assess any lower urinary tract symptoms and cardio-respiratory symptoms such as breathlessness and swelling.

Blood pressure – the number one priority

Effective blood pressure control is the top priority in CKD. For patients without diabetes, NICE recommends a systolic BP in the range 120–139 mmHg and diastolic BP < 90 mmHg. In those with diabetes or significant proteinuria (urine ACR > 70 mg/mmol), systolic BP should be in the range 120–129 mmHg and diastolic BP < 80 mmHg.

Emphasise ways that the patient can take control of his or her own blood pressure. Home blood pressure meters are inexpensive. Most arm cuff meters have been validated as accurate, but wrist meters do not give reliable readings. In our experience, patients do not become anxious from measuring their own blood pressure. They may become insistent that their blood pressure is not adequately controlled, but that is to be welcomed.

Even though few doctors wear white coats, the ‘white coat’ effect can be very marked and lead to inappropriate escalation of medication. Home readings are a much better guide to long-term outcomes. Set a simple blood pressure goal: ‘The top number should be less than 140 almost every time you check it.’

Patients often ask about possible dietary changes that may lower blood pressure. There is strong evidence that reducing daily salt intake increases the antihypertensive effect of drugs such as ACE inhibitors. In patients with CKD, lower salt intake is associated with a lower risk of CKD stage 5 (Vegter et al. 2012). Patients should not add salt at the table and should avoid processed foods with a high salt content. Salt substitutes may contain large amounts of potassium chloride, which is contraindicated in some CKD patients.

Advise patients to reduce their salt intake over a period of weeks. A rapid and large reduction will mean food suddenly tastes bland and your advice will probably be ignored. Reduce slowly and the taste buds will adapt to the new diet and food will continue to be enjoyable. Indeed, a variety of subtle flavours will emerge when the overwhelming taste of salt is removed.

Patients with CKD and hypertension lose the usual night-time ‘dip’ in blood pressure. Advise them to take at least one of the blood pressure agents at bedtime to maximise the blood pressure-lowering effect during sleep. Simply changing the time the tablets are taken can reduce the risk of cardiovascular events by two-thirds (Hermida et al. 2011).

Apart from blood pressure control, there is no convincing evidence to support other interventions for slowing the decline in GFR. Low-protein diet was studied in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study. The MDRD eGFR formula was the main product of this study – a low-protein diet did not have a significant effect. Similarly, lowering cholesterol does not slow the rate of decline in GFR.

Healthy living, healthy kidneys

Lifestyle advice for people with CKD is no different to general healthy living advice: stop smoking, drink alcohol in moderation and not every day, eat more fruit and vegetables, take regular exercise and, if obese, lose weight.

Smoking is a risk factor for the development CKD and is associated with more rapid decline in GFR and increased mortality. Knowledge that the kidneys are affected may help motivate a patient to quit. Signpost patients to smoking cessation support at every review.

Excess alcohol consumption contributes to CKD through its link with obesity and cardiac disease. Incorporate brief intervention, including an alcohol screening questionnaire such as the AUDIT-C, into the review.

Drinking two or more cola drinks per day, diet or regular, has been associated with a doubling of the risk of CKD. Other carbonated drinks showed no association. This may be due to the phosphoric acid in cola.

Many fruits and vegetables have an important acid-neutralising effect. If taken in sufficient amounts, they are as effective as sodium bicarbonate tablets in reducing urinary albumin excretion and other markers of kidney injury (Goraya et al. 2012).

Thirty minutes of moderately intense physical activity should be taken on a regular basis, ideally five times a week. Kidney disease is not worsened by exercise, and the health benefits of exercise extend even to patients on dialysis. Some kidney dialysis units offer exercise programmes that patients can do during the dialysis treatment.

Obesity has mixed associations with kidney disease and outcomes. It leads to increased proteinuria, and extreme obesity can cause glomerular damage (focal segmental glomerulosclerosis). On the other hand, in patients with CKD stage 5, obesity loses its association with mortality. This is possibly because it protects against malnutrition in patients with severe chronic disease.

How can I use ACE inhibitors and ARBs safely?

Drugs that inhibit the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) are used frequently in patients with CKD. They include angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors, drug names ending in –pril), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs, drug names ending in –sartan) and renin inhibitors, all of which act to reduce the effect of angiotensin II (A-II). A-II is a potent vasoconstrictor that also stimulates the adrenal glands to produce aldosterone. Aldosterone stimulates potassium excretion by the kidney tubules and is blocked by drugs such as spironolactone.

If you use them appropriately, ACE inhibitors and ARBs can protect kidney function and reduce the risks of heart failure and mortality; use them inappropriately and they can cause acute kidney injury, severe hyperkalaemia and precipitate dialysis. How can you get the balance right?

To understand how these drugs can heal and harm, you need to understand how A-II affects the kidney. A-II acts on the small muscular blood vessels that take blood away from the glomeruli (the efferent arterioles). Vasoconstriction of these vessels is needed to maintain pressure in the blood vessels behind them, i.e. within the glomeruli. This hydrostatic pressure forces fluid through the pores in the endothelial cells and across the glomerular basement membrane; in other words, it causes glomerular filtration.

Imagine you are using a garden hose on a summer’s day, spraying your flowerbeds and anybody nearby. To get a strong spray you need the tap turned full on. This is like a high arterial blood pressure. To vary the spray you change the resistance on the end of the hose. The harder you press with your thumb, the greater the resistance, the higher the pressure and the further the spray goes (Figure 3.9). This is like varying the resistance in the efferent arterioles – vasoconstriction increases glomerular filtration.

Figure 3.9 The hosepipe analogy for glomerular filtration. Glomerular filtration requires high pressure in the glomerular capillaries. Constriction of the arteriole leaving the glomerulus is like pressing your thumb on a hose. Resistance to flow out of the hose increases the pressure and creates the spray.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree