Overall Bottom Line

- HIV co-infection accelerates both hepatitis C and hepatitis B natural history leading to faster progression to and increased incidence of cirrhosis, HCC and death.

- HIV/HCV co-infected patients have twice the risk of developing cirrhosis and a sixfold increased risk of liver failure compared with those with HCV alone.

- Early diagnosis of viral hepatitis, accurate assessment of liver fibrosis, aggressive approach to hepatitis treatment and regular screening for HCC and EV can be life-saving in this high-risk population.

- HIV-infected individuals should all be tested for antibodies to HAV, HBV and HCV at least at the time of initial HIV diagnosis, and thereafter depending on ongoing risk factors.

- Susceptible individuals should be vaccinated according to the recommended schedule, ideally when CD4+ T-cells are above 200 cells/mm3.

- Outbreaks of HCV among HIV-infected MSM have been reported in Europe, Australia and the USA.

- Treatment of acute HCV is nearly always successful when initiated early.

- Effective treatment of HBV and HCV in HIV co-infected patients increases survival.

- New DAAs have revolutionized the treatment of HCV in HIV-infected patients.

Section 1: Background

Definition of disease

- Chronic hepatitis B and C (chronic viral hepatitis) are defined as persistent infections of the liver lasting for at least 6 months and leading to hepatocellular necrosis and inflammation, with or without associated fibrosis.

- In HIV co-infected patients, chronic viral hepatitis is associated with accelerated liver fibrosis progression compared with HCV-infected patients without HIV.

Disease classification

- Hepatitis B and C can be acute or chronic.

- Acute infection is defined as infection during the first 6 months following exposure.

- Chronic infection is defined as infection persisting more than 6 months after exposure.

Incidence/prevalence

- The estimated prevalence of chronic HCV in HIV-infected individuals is around 25–30% in the USA.

- The estimated prevalence of chronic HBV in HIV-infected individuals is around 7–10 % in the USA.

- HCV incidence has been rising in HIV-infected MSM from an estimated range of 5.5–8.1 per 1000 person-years in 1995 to 23.4–51.1 per 1000 person-years in 2007.

Economic impact

- For HCV, in the 10-year period from 2010 to 2019:

- The direct medical cost of chronic HCV infection is projected to exceed $10.7 billion.

- The societal cost of premature mortality attributed to HCV infection is projected to be $54.2 billion.

- The cost of morbidity from disability associated with HCV infection is projected to be $21.3 billion.

- The direct medical cost of chronic HCV infection is projected to exceed $10.7 billion.

- In a model of cost-effectiveness of HCV treatment in a cohort of 35-year-old HIV-co-infected patients with a mean CD4+ T-cell count of 350 cells/μL and moderate HCV, the average discounted quality-adjusted life expectancy was 83.8 months, and lifetime costs were $139,000.

- CDC projects that each one million high-risk adults vaccinated against HBV could save up to $100 million in future direct medical costs by preventing 50 000 new hepatitis B infections, 1000 to 3000 chronic hepatitis B infections, and 150–450 deaths from cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Etiology

- Hepatitis C is caused by HCV, a small, enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae.

- Following acute HCV, HIV-infected patients have a significantly lower rate of spontaneous clearance compared with HIV-uninfected patients, with 10–15% clearance rate compared with 15–25%.

- Hepatitis B is caused by HBV, a small, enveloped virus of the family Hepadnaviridae. It is a virus with circular, partially double-stranded DNA, with two DNA strands of different lengths.

- Spontaneous clearance of HBV after infection in the adult age group is about 90% and is significantly lower in HIV-infected patients.

Pathology/pathogenesis

- HCV is spread primarily through contact with blood. HCV is not typically transmitted between heterosexual partners in regular relationships after controlling for other risk factors. However, underlying STIs and HIV may increase risk of heterosexual transmission.

- Sexual transmission among MSM is well described and is largely responsible for the acute HCV outbreaks in HIV-infected MSM. The presence of several activities and conditions that disrupt anal mucosal integrity (traumatic sex, sex with visible blood, genital ulcerative diseases, use of sex toys) were frequently noted in instances of assumed sexual transmission.

- HBV is transmitted primarily through sexual contact and contact with blood (IVDU) in countries of low prevalence. Vertical transmission is the main mode of transmission in countries of high prevalence. Chronic HCV results from an inefficient or unsustained HCV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses. HBV and HCV are not cytopathic viruses. Infected hepatocytes trigger host cellular immunologic responses that eventually lead to destruction and clearance of infected hepatocytes. Prolonged liver injury leads to fibrosis. Cirrhosis is the result of continuing liver injury and fibrosis. The risk of developing cirrhosis and complications such as HCC secondary to HCV or HBV is increased in HIV-nfected patients and is associated with low CD4+ T-cell counts.

Predictive/risk factors

Risk factors for fibrosis progression in HIV/HCV co-infected patients

- Age at time of infection.

- Older age.

- Male sex.

- Low CD4+ T-cell count (<200 cells/mm3).

- Detectable HIV viral load.

- Hepatic steatosis.

- Insulin resistance/diabetes.

- Alcohol abuse.

- Co-infection with HBV.

Risk factors for fibrosis progression in HIV/HBV co-infected patients

- Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive.

- Higher HBV DNA levels.

- Older age.

- Elevated ALT levels.

- Alcohol abuse.

- Co-infection with HCV.

Section 2: Prevention

Clinical Pearls

- The key to prevention of HCV is avoidance of exposure to infected blood and blood products and protected sexual intercourse among MSM.

- HBV can be prevented by vaccination, vaccination and immunoglobulin administration to babies born from infected mothers, and avoidance of exposure to infected blood and protected sexual intercourse.

- HBV is 100 times more infectious than HIV and HCV is 10 times more infectious than HIV by direct blood-to-blood contact.

Screening

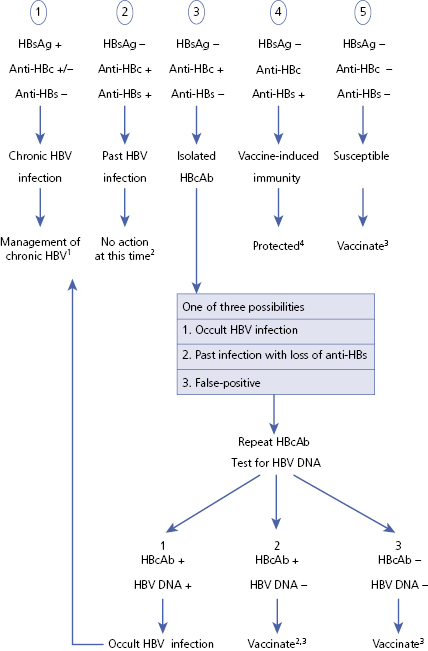

- Screening for HBV infection is mandatory in all HIV-infected patients because of shared routes of transmission. The presence of HBV infection also influences the decision of when to start ART, what ART to start and future HIV management decisions. Initial testing should include HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc (Algorithm 7.1).

- Screening for HCV infection is mandatory in all HIV-infected patients at least at the time of initial HIV diagnosis. The updated New York State Guidelines on HCV/HIV-co-infection recommend that HIV-infected patients with continued high-risk behaviors who are seronegative for HCV at baseline receive annual testing thereafter. Many clinicians measure HCV Ab as often as every 3 months in sexually active MSM. Initial testing includes anti-HCV antibody test and HCV RNA in those with positive antibody test. HCV antibody may be negative in the acute phase and HCV RNA may be required for diagnosis.

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 7.1 Screening algorithm for HBV in HIV-infected patients: five scenarios

1 See Algorithm 7.4.

2 Keep in mind for future treatment decisions if immunosuppression state anticipated.

3 See Algorithm 7.2.

4 Follow-up HBsAb is warranted if high-risk behavior or immunosuppression.

– – – – – – – – – –

Primary prevention

- Primary prevention interventions that have led to reductions in HIV incidence have not been as successful in reducing HCV incidence.

- There is observational data for needle exchange programs in reducing prevalence of HCV in IV drug users.

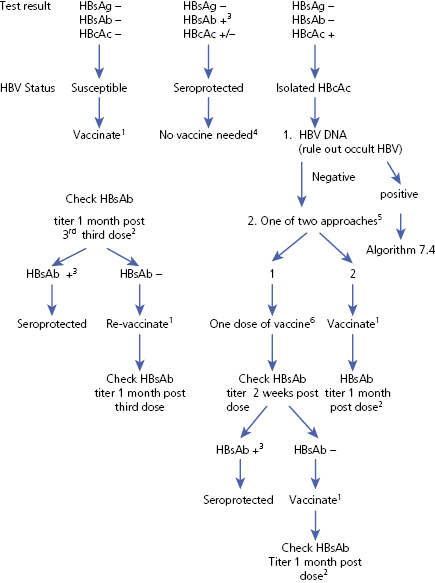

- HBV vaccination of susceptible HIV-infected individuals is recommended (see Algorithm 7.2 – HBV vaccination of HIV-infected patients) as well as vaccination and administration of immunoglobulins to babies born to HIV/HBV-infected mothers who are more likely to vertically transmit HBV than HIV-uninfected mothers.

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 7.2 HBV vaccination of HIV-infected patients

1 Vaccinate with 20 μg of either of the available anti-HBV vaccines at 0, 1 and 6 months. Some experts recommend using 40 μg.

2 HIV-infected patients have decreased immune response to HBV vaccine and should have anti-HBs titer checked 1 month following the third dose of vaccine.

3 HBsAb titer >10 IU/mL.

4 Be mindful of HBcAb if immunosuppression state is anticipated, then HBV prophylaxis is recommended.

5 Another approach would be to check for HBeAb. If positive, then no vaccination required.

6 20 μg of either available anti-HBV vaccines.

– – – – – – – – – –

Secondary prevention

- Treatment of both HBV and HCV reduces liver-related complications and increases survival in HIV-infected individuals.

- Patients should be counseled to avoid high-risk behaviors after HCV clearance as re-infection can occur.

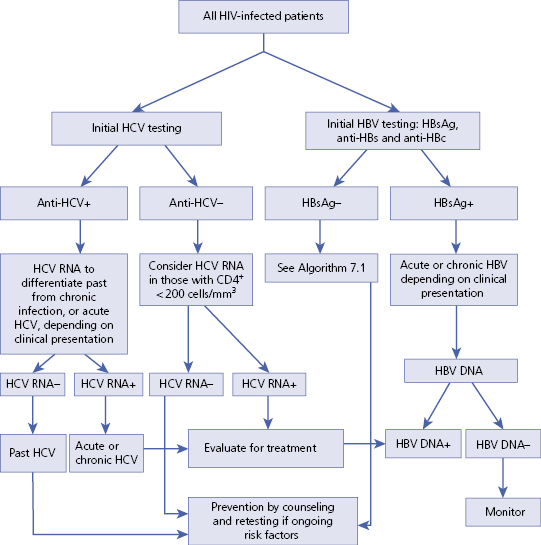

Section 3: Diagnosis (Algorithm 7.3)

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 7.3 Diagnosis of HBV and HCV in HIV-infected patients

– – – – – – – – – –

Bottom Line

- All HIV-infected patients are at risk for HBV and/or HCV co-infection because of shared routes of transmission.

- The physical examination is usually negative unless the patient has progressed to advanced liver disease.

- ALT and AST are highly elevated during acute HBV and HCV infections. In chronic infections, elevations of ALT above the upper limit of normal (19 IU/L for women and 30 IU/L for men) are frequent, but not universal, and the levels fluctuate.

- Diagnosis of both HBV and HCV in HIV-infected patients is done by the combination of serologic testing and nucleic acid testing (HCV RNA and HBV DNA)

- In HIV-infected patients, staging of fibrosis with liver biopsy is not mandatory to guide treatment decisions in any HCV genotype and should not be a barrier to HCV treatment.

Differential diagnosis

- Viral hepatitis B and C are straightforward to diagnose. They are often first suspected in patients who present with elevated liver enzymes.

- They can also co-exist with other liver diseases, especially non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver disease. Antiretroviral liver toxicity is a diagnosis of exclusion.

| Differential diagnosis | Features |

|---|---|

| Other viral hepatitides (A, B, C, D, E) Hepatitis B can flare at time of discontinuation of HBV-active ART or because of HBV resistance | Serologic markers or nucleic acid testing |

Antiretroviral liver toxicity (four mechanisms)

| Temporal relationship with ART initiation, but may present late Diagnosis of exclusion Liver biopsy shows different features depending on mechanism of liver toxicity |

| Opportunistic liver infection | In AIDS patients with severe immunosuppression (<200 CD4+ T-cells, usually <50 CD4+ T-cells) |

| NASH | Associated or not with ART |

| Alcoholic steatohepatitis | History of alcohol abuse Liver biopsy shows centrilobular inflammatory infiltration and Mallory’s hyaline |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Positive autoimmune serum markers Liver biopsy shows plasma cell infiltration |

Typical presentation

- Acute HCV and HBV infections in HIV-infected patients are usually asymptomatic. When symptomatic, patients may present with RUQ pain, nausea and vomiting with or without jaundice.

- Chronic HCV and HBV are usually asymptomatic. They can be associated with fatigue or they can present with symptoms and signs of ESLD including ascites, EV with or without bleeding, jaundice and encephalopathy. HCC may become symptomatic in the later stages.

Clinical diagnosis

History

- History of present illness should include identification of risk factors for transmission of HBV and HCV and potential timing of infection. The patient’s symptoms are usually non-specific, the most common being fatigue. Signs and symptoms of extra-hepatic manifestations of HCV, cirrhosis and portal hypertension should be included in the history.

Physical examination

- Look for signs of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Look at general appearance for anorexia, scleral icterus and temporal atrophy. Look for asterixis.

- Look specifically at the skin for jaundice, upper chest vascular spiders, abdomen vascular collaterals (caput medusa), and palmar erythema, and at the nails for Terry’s nails and clubbing.

- Look for hepato/splenomegaly, hardening of the liver, presence of a mass and ascites at abdominal examination.

- Look for gynecomastia and testicular atrophy.

Laboratory diagnosis

List of laboratory tests to diagnose HCV

- HCV antibody (anti-HCV) test.

- HCV RNA.

- HCV genotype if positive HCV RNA.

List of laboratory tests to diagnose HBV

- HBsAg, HBsAb, and HBcAb.

- HBeAg, HBeAb and HBV DNA if HBsAg +.

List of laboratory tests to help assess disease severity

- CBC with differential and platelets.

- Comprehensive metabolic panel including GGT.

- PT/PTT and INR.

- AFP.

List of other laboratory tests useful at initial evaluation

- Anti-HAV.

- Ferritin, iron/TIBC.

- ANA, AMA.

- Ceruloplasmin.

- Thyroid function tests and thyroid antibodies.

- Lipid panel.

- Total insulin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree