Overall Bottom Line

- HCV is a major healthcare problem with an estimated 180 million people affected worldwide. It remains a leading cause for liver transplantation in the USA and accounts for roughly 8–13 000 deaths per year in this country.

- Spontaneous clearance of the virus is rare and 80–100% will become chronically infected.

- The primary goal of HCV treatment is cure, or eradication of the virus, which can be achieved successfully with currently approved combination therapies.

- Cure of HCV will prevent disease progression, reduce cirrhosis and its associated complications and decrease the risk of developing HCC.

- PEG-IFN and RBV remain the backbone of therapy for those eligible for treatment of HCV and the standard of care for genotypes other than 1.

- PIs BOC and TVR are recently approved drugs that can dramatically increase SVR when used in conjunction with current therapy. Their approval has changed the standard of care in chronic HCV treatment, for genotype 1 HCV, to include PEG-IFN, RBV and either of these two PIs.

- Treatment of acute HCV is nearly always successful when initiated early.

Section 1: Background

Definition of disease

- Hepatitis C is an inflammatory liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus. Transmission of the disease is blood-borne and without treatment almost 50% will progress to liver cirrhosis.

Incidence/prevalence

- In the 2006 NHANES III study the prevalence of anti-HCV in the USA was 1.6%, equaling about 4.6 million people: 1.3% of the population was infected chronically.

- The WHO estimates that worldwide about 3% of the population has been infected with HCV and that almost 170 million people are chronically infected.

- Egypt has the highest worldwide prevalence with 9% of the country infected (up to 50% in rural areas).

- Incidence of the disease is difficult to evaluate given that the vast majority of newly infected individuals are completely asymptomatic.

- Genotypes 1, 2 and 3 have worldwide distribution. 1a and 1b comprise 70% of the HCV infections in the USA. Genotype 3 is seen in younger populations and in South Asia and genotype 4 is common in Egypt. Genotype 5 is found predominantly in South Africa and genotype 6 in Southeast Asia.

Economic impact

- In 1998, the estimated cost burden of this disease was 1 billion dollars.

- This figure is expected to quadruple between 2010 and 2020.

Etiology

- The causative agent of hepatitis C is the hepatitis C virus.

- HCV is an enveloped single-stranded positive sense RNA virus.

- HCV belongs to the Flaviviradae family.

- There are six HCV virus genotypes based on genetic variations within virus isolates. Genotype and subtype are important in determining treatment duration.

- Transmission is blood-borne and usually transmitted via the sharing of infected needles. Transmission through sexual contact is rare compared with hepatitis B and HIV.

Pathology/pathogenesis

- After blood-borne inoculation, the virus is taken up by hepatocytes by means of one or multiple viral surface receptors. Once inside, the virus uncoats and releases its genome for mass replication.

- The HCV virus and its proteins have been shown to induce fibrosis directly through interference of cell activation pathways.

- Viral proteins may also lead to fibrosis secondarily through induction of liver steatosis. Implicated proteins include core and NS5A proteins.

- HCV genotype 3 has been suggested to be directly involved in steatosis as treatment of this genotype leads to complete resolution of steatosis.

Predictive/risk factors

- Risk factors for accelerated disease progression:

- Older age at time of infection.

- Male gender.

- Presence of steatosis.

- Other co-morbid illnesses.

- Co-infection with HIV or HBV.

- Persistence of ALT elevations.

- Host genetics.

- Heavy ETOH use.

- Older age at time of infection.

Section 2: Prevention

Clinical Pearls

- The key to preventing HCV infection is to educate patients about avoidance of exposure to infected blood and contaminated instruments, especially drug paraphernalia. Efforts are needed to educate high risk populations, including intravenous drug users, intranasal drug users and MSMs.

- Primary prevention interventions that have led to reductions in HIV incidence have not been as successful in reducing HCV incidence.

- There is observational data for needle exchange programs in reducing prevalence of HCV in IV drug users.

Counseling tips to reduce transmission of HCV

- Those who are HCV infected should avoid sharing toothbrushes, dental or shaving equipment and cover bleeding wounds.

- Counsel to stop using illicit drugs or not share works. Those who continue to inject drugs should be counseled to avoid reusing or sharing syringes, needles, straws, water, swabs and cotton, or other paraphernalia and to dispose safely of syringes and needles after use. Direct active users to needle exchange programs, where available.

- Latex condoms should always be used in HCV-positive persons who are not in long-term monogamous relationships.

- HCV-infected persons should be advised to not donate blood, body organs, other tissues or semen.

Screening

- History of ever having used illicit drugs via injection or intranasal route.

- Populations with HIV, on dialysis, and those with unexplained elevated liver enzymes.

- Transfusion of blood or blood products, or transplantation prior to 1992.

- Children born to HCV-infected mothers.

- Healthcare workers after needle stick injury to known HCV.

- Those born in high-risk endemic areas (Former Soviet Union, Pakistan, Mongolia and Egypt).

- Regardless of HCV risk factors, the CDC recommends one-time testing for all persons born between 1945 and 1965. This population has been shown to have a high prevalence of HCV infection and related disease.

Secondary prevention

- After SVR has been obtained with HCV treatment, patients can be re-infected. Always counsel patients to avoid high risk behaviors in order to avoid re-infection.

- Special attention should be paid to active drug users or prior drug users with high risk of relapse, and MSM who engage in unprotected sexual activity.

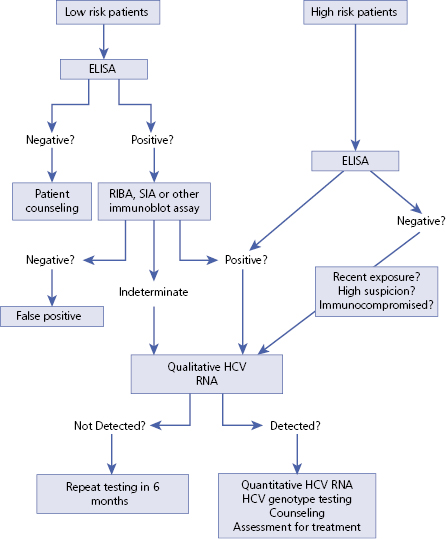

Section 3: Diagnosis (Algorithm 6.1)

– – – – – – – – – –

Algorithm 6.1 HCV diagnosis

– – – – – – – – – –

Clinical Pearls

- Generally patients with acute HCV are asymptomatic. They may have fatigue, nausea, malaise, occasional RUQ pain and rarely jaundice.

- Jaundice, hepatomegaly and RUQ tenderness may be noted on physical examination.

- Liver function tests, HCV antibody, quantitative HCV RNA should be sent for initially.

- HCV RNA can be detected as early as 2 weeks after exposure but antibody may not be detected until between 8 and 12 weeks. If HCV RNA is detected, HCV genotyping should be sent.

Differential diagnosis

| Differential diagnosis | Features |

|---|---|

| Hepatitis B virus infection | Family history, from high endemic area, and positive hepatitis B serology |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | Drinking history, 2:1 AST/ALT ratio and negative hepatitis serologies |

| NASH (fatty liver) | Large body habitus or increased abdominal adiposity on physical examination. Negative hepatitis serologies |

| Wilson disease | Family history of disease, Kayser–Fleischer rings on physical examination. Check serum ceruloplasmin, 24 hour urine copper measurements |

| DILI | Presenting symptoms may be similar but hepatitis serologies will be negative. Temporal association with elevated LFTs and initiation of medication/s |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | ANA, SMA, anti-LKM may be positive on laboratory investigations. Affected population tends to be women with other autoimmune history or family history |

Typical presentation

- Patients are usually asymptomatic from acute HCV infection. Those who present with symptoms usually have non-specific ones such as fatigue, nausea, malaise, occasionally RUQ pain and rarely jaundice. These symptoms are self-abating and last from 2 to 12 weeks. Chronic HCV infection is usually detected after abnormal LFTs are noted on routine screening by primary care physician. Most symptoms and complications associated from HCV are secondary to development of cirrhosis.

Clinical diagnosis

History

- Obtain an accurate and comprehensive history. History of the following exposures should be elicited:

- History of ever having used illicit drugs via injection or intranasal route.

- Populations with HIV, on dialysis, and those with elevated liver enzymes of still unclear etiology.

- MSM.

- Transfusion or transplantation prior to 1992.

- Children born to HCV-infected mothers.

- Needle stick injury to known HCV.

- Born in high risk endemic areas (Former Soviet Union, Pakistan and Egypt).

- History of ever having used illicit drugs via injection or intranasal route.

Physical examination

- Inspect the patient’s skin, sclera and tongue for evidence of jaundice. Also assess skin for findings of spider angiomata.

- Inspect abdomen for evidence of bulging flanks or caput medusa. Palpate abdomen and check for hepatosplenomegaly, RUQ tenderness and presence of ascites.

- Other physical examination findings one should look for include: alteration in mental status, palmar erythema, and lymphadenopathy.

Disease severity classification

- Liver biopsy is useful to determine degree of liver injury, but not a requirement.

- Typically a biopsy is not needed in genotypes 2 and 3, if the patient is willing to be treated.

- A number of serologic assays measure indirect markers of liver fibrosis, including Fibroscore, Hepascore, Fibrotest, FIB 4 and APRI. They are all remarkably comparable and can distinguish those with very minimal or advanced fibrosis with good sensitivity and specificity, but are less useful for patients with intermediate stages of fibrosis.

- Liver biopsy: the gold standard for determining degree of fibrosis. It is useful in chronic disease for prognosis, and the decision to treat in those with slow disease progression. The following staging methods are used to identify degree of fibrosis on liver biopsy: Metavir, Ishak, IASL and Batts-Ludwig. Among these, Metavir and Ishak are most widely used, and consist of four and six stages, respectively.

- Transient elastography (Fibroscan): a non-invasive method of determining liver stiffness is highly accurate in detecting cirrhosis in chronic HCV infection but slightly less specific for non-cirrhotic stages of fibrosis. It is approved for use in Europe and Canada.

Laboratory diagnosis

List of diagnostic tests

- HCV antibody – ferritin, iron/total iron binding capacity.

- Quantitative HCV – viral load ANA, AMA.

- HCV genotype – if positive viral load.

- PT and INR – thyroid function tests and thyroid antibody.

- CBC with differential – lipid panel.

- Comprehensive metabolic panel, including ALT, AST, GGT, total bilirubin and direct bilirubin – HBsAg, HBsAb, HBcAb, HAV Ab.

- AFP – HIVAb.

Available imaging techniques

- The main reasons for imaging in HCV are to exclude the existence of other liver diseases, assess severity of disease and to screen for HCC.

- Liver US: in acute HCV there may be decreased liver echogenicity. In chronic HCV there often is increased liver echogenicity. Ultrasound is useful in evaluation of suspected ascites. Ultrasound is not as sensitive as CT and MRI and may not detect subcentimeter HCC.

- CT abdomen: hepatomegaly, diffuse steatosis and gallbladder wall thickening may be noted in HCV infection. In chronic infection CT can aid evaluation for cirrhosis and HCC. Dual phase or triple phase contrast studies are most sensitive in evaluation of HCC.

- MRI abdomen: in HCV may see periportal hyperintensity in T2-weighted images secondary to edema. In chronic infection can evaluate for cirrhosis and HCC – order with contrast.

- Varices, splenomegaly or ascites seen on any imaging modality suggest cirrhosis with portal hypertension.

- Liver US: in acute HCV there may be decreased liver echogenicity. In chronic HCV there often is increased liver echogenicity. Ultrasound is useful in evaluation of suspected ascites. Ultrasound is not as sensitive as CT and MRI and may not detect subcentimeter HCC.

Interpretation of serologic and molecular assays

| HCV antibody | HCV RNA | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | Negative | Negative for HCV infection. Tests should be repeated in 4–6 weeks if clinical suspicion is high |

| Negative | Positive | Acute exposure to HCV or immunosuppressed patient with HCV. Repeat screening at weeks 4 and 12 |

| Positive | Positive | Chronic HCV infection. Consider treatment |

| Positive | Negative | Patient has been exposed but has cleared infection; no treatment necessary |

Potential pitfalls/common errors made regarding diagnosis of disease

- If suspicion for acute HCV is high anti-HCV testing should be repeated even if initial testing is negative, as anti-HCV can be detected in 90% of patients 12 weeks after exposure.

- False-negative anti-HCV also occurs in populations with immunocompromised states such as transplant populations, HIV patients, dialysis patients and those with hypoglobulinemia. In these groups, if suspicion is high, quantitative HCV RNA should be performed.

Important abbreviations and definitions in HCV treatment

| RVR | Rapid virologic response; HCV RNA undetectable (UD) at week 4 |

| EVR | Early virologic response; HCV RNA UD at week 12 |

| eRVR | Extended rapid virological response; HCV RNA UD at weeks 4 and 12 |

| pEVR | Partial early virological response; 2 Log drop in HCV RNA at week 12 |

| cEVR | Complete early virological response; HCV RNA UD at week 12 |

| SVR | Sustained virologic response; UD 24 weeks after treatment completion |

| PR | Partial non-response; >2 log decrease at week 12, but detectable at weeks 12 and 24 |

| DVR | Delayed virologic response; >2 log decline but detectable at week 12 and UD at week 24 |

| NR | Null response; <2 log decrease at week 12 |

| BT | Breakthrough of HCV RNA any time after being UD |

| EOT | End of treatment |

| RGT | Response guided therapy |

| UD | Undetectable |

| DAA | Direct Acting Antiviral Agent |

| PI | Protease Inhibitor |

| LLOD | Lower limit of detection. The lowest limit of HCV concentration that can be detected with a 95% probability to determine presence or absence of HCV RNA. True non-detectability on treatment is demonstrated when the HCV RNA is below the LLOD |

| LLOQ | Lower limit of quantification. Smallest amount of HCV RNA that can be detected and accurately quantified |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree