) started in 1958 in Japan with Matsunaga’s intracolonic use of the gastrocamera under fluoroscopic control, and subsequently Niwa’s development of the “sigmocamera.” Not surprisingly, these instruments had application only in the hands of pioneer enthusiasts. Following Hirschowitz’s development of the fiberoptic bundle in 1957–1960 for use in prototype side-viewing gastroscopes, several colorectal enthusiasts started developments. The first was Overholt in the USA, who started on prototypes in 1961, performed the first fiberoptic flexible sigmoidoscopy in 1963, and finally introduced a commercial forward-viewing short “fiberoptic coloscope” in 1966 (American Cystoscope Manufacturers Inc.). Meanwhile, Fox in the UK and Provenzale and Revignas in Italy had achieved imaging of the proximal colon with passive fiberoptic viewing bundles or side-viewing gastroscopes inserted through a tube placed radiologically or pulled up by a swallowed transintestinal “guide string and pulley” system.

In 1969 Western researchers were surprised by the production by Japanese engineers (Olympus Optical and Machida) of remarkably effective colonoscopes, which combined the precise two-way angulation and torque-stable shaft of the latest gastrocameras with superior fiberoptic bundles, although initially the limitations of Japanese glassfiber technology restricted angulation to around 90° (due to fragile fibers) and the angle of view to 70°.

Gastric snare polypectomy was first described by Niwa in Japan in 1968–9, and snaring of colon polyps was pioneered in 1971 by Deyhle in Europe and Shinya in the USA.

In the mid-1970s four-way acutely angulating instruments were introduced, and in 1983 the video endoscope arrived (Welch-Allyn, USA). Although small-scale colonoscope production continued for a time in the USA, Germany, Russia, and China, the combined mechanical, optical, and electronic know-how of the Japanese camera manufacturers now controls the conventional colonoscope market.

Indications and limitations

The place of colonoscopy in clinical practice depends on local circumstances and available endoscopic expertise. Although colonoscopy is considered the “gold standard” exam, “virtual” colography by computed tomography (CT) or even double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) alone may be considered by some to be adequate in “low-yield” patients where therapeutic intervention, histology, or fine-focus diagnosis is not needed. Similarly, on the grounds of logistics, safety, and patient acceptability, flexible sigmoidoscopy has a significant role in clinically selected patients with minor symptoms and is being introduced as part of population colorectal cancer screening in the UK.

Double-contrast barium enema

DCBE is a safe (one perforation per 25 000 examinations) way of showing the configuration of the colon, the presence of diverticular disease, and the absence of strictures or large lesions. However, even high-quality DCBE has significant limitations, including missing large lesions because of overlapping loops (particularly in the sigmoid region), to misinterpreting between solid stool and neoplasm or between spasm and strictures, with particular inaccuracy for flat lesions such as angiodysplasia or minor inflammatory change and small (2–5 mm) polyps. Where colonoscopy services are overstretched, and CT colography is not routinely available, barium enema may be used in “low yield” patients—those with pain, altered bowel habit or constipation; it also shows extramural leaks or fistulae, which are invisible to the endoscopist.

Computed tomography colography

CT colography (“virtual colonoscopy”) has replaced barium enema as the radiological investigation of choice for the colon, with the advantages of being quicker and not filling the colon with dense contrast medium. CT colography does require technical expertise of the radiographer in perfoming it and the radiologist who interprets it. A few patients who are very difficult to colonoscope for reasons of anatomy or postoperative adhesions may be best examined by combining limited left-sided colonoscopy—the most challenging area for imaging but with the highest yield of significant pathology—with virtual colography or barium enema to demonstrate the proximal colon. Virtual colography has the advantage that it can be performed before or after colonoscopy and with the same bowel preparation, although the majority of procedures are now performed with limited or no bowel preparation and “faecal tagging” using water-soluble contrast agents. CT colography requires radiation dosage comparable to that of DCBE, although dedicated CT protocols limit radiation as much as possible.

Colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy

Colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy achieve more than contrast radiology or virtual colography because of their greater accuracy and histologic and therapeutic capabilities. Color view and biopsy makes total colonoscopy particularly relevant to patients with bleeding, anemia, bowel frequency, or diarrhea. Flexible sigmoidoscopy alone may be sufficient for some patients, such as those with left iliac fossa pain or bright red per-rectal bleeding. Because of near pinpoint accuracy and therapy, colonoscopy scores for any patient at increased risk for cancer—in whom detection and removal of all adenomas is important for the patient’s future and as a predictor of long-term risk. Colonoscopy is thus the method of choice for many clinical indications and for cancer surveillance examinations and follow-up (Table 6.1). Endoscopy is also particularly useful in the postoperative patient, either to inspect in close-up (and biopsy if necessary) any deformity at the anastomosis or to avoid the difficulties of achieving adequate distension in patients with a stoma.

Table 6.1 Colonoscopy: indications and yield.

| High-yield indications | Low-yield indications |

|---|---|

| Anemia/bleeding/occult blood loss | Constipation |

| Persistent diarrhea | Flatulence |

| Inflammatory disease assessment | Altered bowel habit |

| Genetic cancer risk | Pain |

| Abnormality on imaging | |

| Therapy |

Combined procedures

The combination of two procedures (colonoscopy and virtual colography or DCBE) has potential advantages. If carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation is used for colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy, the colon will be absolutely deflated within 10–15 minutes and DCBE can follow immediately. As distension is a routine part of virtual colography, it is an ideal procedure to combine with colonoscopy. DCBE can be made difficult if the proximal colon is already air-filled, so problematic to fill and coat with barium. Colonoscopic biopsies with standard-sized forceps are no contraindication to distending the colon for subsequent DCBE or CT colography. Pedunculated polypectomy should also be safe, but the likelihood of deep electrocoagulation during sessile polypectomy, however small, contraindicates use of distension pressure. DCBE perforation is rare, but barium peritonitis can be fatal.

Limitations of colonoscopy

- Incomplete examination can be due to inadequate bowel preparation, uncontrollable looping, inadequate hand-skills, or an obstructing lesion. Unless the ileo-cecal valve is reached and positively identified with clear views of the cecal pole, completion has not been proved.

- Gross errors in colonoscopic localization and “blind spots” are possible even for expert endoscopists. Blind areas, with the possibility of missing very large lesions, occur especially in the cecum, around acute bends and in the rectal ampulla. Colonoscopic examination, rigorously performed, can probably approach 90% accuracy for small lesions, but will never be 100%. A “back to back” colonoscopy series, in which the patient was colonoscoped twice by two expert endoscopists, showed only a 15% miss rate for polyps under 1 cm diameter. However, every colonoscopist has experienced the chagrin of seeing a large polyp during insertion, but missing it entirely during withdrawal when the colon is crumpled after straightening the scope.

Hazards, complications, and unplanned events

Colonoscopy, despite its virtues, is more hazardous than diagnostic alternative studies (historically around one perforation per 1500 colonoscopic examinations, although much lower in recently published series, against perforations in 1 : 25 000 barium enemas or CT colography exams). Unskilled endoscopists needing to use heavy sedation or general anesthesia to cover up ineptitude are likely to run greater risks. It should therefore not be regarded as failure to abandon a tough colonoscopy in favor of immediate CT colography, when “pressing on regardless” could result in an avoidable perforation and subsequent complications.

Instrument shaft or tip perforations

These perforations are usually caused by inexperienced users and the use of excessive force when pushing in or pulling out. In a pathologically fixed, severely ulcerated, or necrotic colon, however, forces that would be safe in a normal colon may be hazardous. Either the tip of the instrument or a loop formed by its shaft can perforate. Shaft loop perforations are characteristically larger than expected, so, if in doubt, surgery should be advised. When surgery has been performed soon after apparently uneventful colonoscopy, small tears have been seen in the ante-mesenteric serosal aspect of the colon and hematomas found in the mesentery. In other cases the spleen has been avulsed during straightening maneuvers when the tip is hooked around the splenic flexure.

Air pressure perforations

These include “blow-outs” of diverticula, “pneumoperitoneum,” and ileo-cecal perforation following colonoscopy limited to the sigmoid colon. Surprisingly high air pressures result if the scope tip is impacted in a diverticulum or if insufflation is excessive, for instance when trying to distend and pass a stricture or segment of severe diverticular disease. Use of CO2 insufflation minimizes these serious risks post-procedure, as it is so rapidly absorbed. Diverticula are thin-walled and have also been perforated with biopsy forceps or by the instrument tip. It is surprisingly easy to confuse a large diverticular orifice with the bowel lumen or to mistakenly identify an inverted diverticulum, usually in the proximal colon, as a small sessile polyp.

Hypotensive episodes

Hypotensive episodes, even cardiac or respiratory arrest, can be provoked by the combination of oversedation and the intense vagal stimulus of forceful or prolonged colonoscopy. Hypoxia is particularly likely in elderly patients, but should be a thing of the past if pulse oximetry (or CO2 capnography) is routinely used and nasal oxygen given prophylactically to sedated patients.

Infection

As mentioned elsewhere, prophylactic antibiotics are rarely indicated before colonoscopy, then only for well-defined groups such as severely immunocompromised patients, and possibly those with ascites or on peritoneal dialysis. However, Gram-negative septicemia can result from instrumentation (especially in neonates or the elderly) and unexplained post-procedure pyrexia or collapse should be investigated with blood cultures and managed appropriately.

Management following complications

Therapeutic procedures inevitably increase the risk of complications, including dilatations (4% of which resulted in perforations in our series), electrocoagulation of bleeding points or sessile polypectomies. However, the hazards are remarkably infrequent compared with the morbidity and mortality considered acceptable for surgery. To generalize (and perhaps exaggerate), endoscopic misadventure risks surgery; surgical misadventure risks death. The endoscopist should therefore be on guard for problems that can occur and should only undertake therapeutic procedures with the knowledge of a back-up surgical team.

It is also worth remembering, however, that fatalities have also been reported after colonoscopic perforation followed by unnecessary surgery (rather than relying on conservative management with antibiotic cover). The decision whether or not to operate after a complication can be a subtle one, but the maxim should be “if in doubt, operate”—although the surgeon consulted needs to be aware of the particular endoscopic circumstances. Most therapeutic perforations will be small and occur in a well-prepared colon, so they may sometimes be considered for conservative management. For instance, perforation following point electrocoagulation of an angiodysplasia in the cecum has a reasonable chance of sealing off spontaneously (with the patient immobilized and on antibiotics). By contrast, an unexplained perforation after a difficult and forceful colonoscopy, especially if bowel preparation was poor, indicates exploratory surgery because there may be an extensive rent in the colon.

Safety

Safety during colonoscopy comes from gentle technique and avoiding pain (or oversedation, which masks the pain response as well as contributing pharmacological hazards). Before starting a colonoscopy it is impossible to know if there are adhesions, whether the bowel is easily distensible, and whether its mesenteries are free-floating or fixed; pain is the only warning that the bowel or its attachments are being unreasonably strained. The endoscopist must respect any protest from the patient; a mild groan in a sedated patient may be equivalent to a scream of pain without sedation. Moreover, it is hazardous to give repeated doses of sedatives intravenously, effectively anesthetizing the patient without an anesthetist being present. It is safer in such cases to abandon the procedure and reschedule as a formal anesthetic procedure. Total colonoscopy is not always technically possible, even for experts.

If there is a history of abdominal surgery or sepsis, or if the instrument feels fixed and the patient is in pain, the correct course is usually to stop. The experienced endoscopist learns to take time, to be obsessional in steering correctly and managing loops dexterously, but to be prepared to withdraw from any difficult situation and if necessary to try again after position change or other appropriate maneuver. Too often the beginner has a relentless “crash and dash” approach, and may be insensitive to the patient’s pain because it occurs so often.

Despite its potential hazards, skilled colonoscopy is amazingly safe; it is certainly justified by its clinical yield and the high morbidity of colonic surgery (which would often be the alternative). For the less skilled endoscopist, partnership with CT colography in “difficult” cases should reduce the risks—with re-referral to an expert if pathology is found.

Informed consent

Obtaining full informed patient consent is essential before an invasive procedure such as colonoscopy, with its potential for complications. The patient should understand the rationale for undergoing the procedure, its benefits, risks, limitations, and alternatives, and have an opportunity to ask the doctor any questions. Precise approaches to the explanation of risks vary from country to country, and should probably be tailored to some extent to the perceived insights and anxieties of the individual patient. Some patients wish to know everything, some would be distressed to have scary and unlikely minutiae (such as “the unlikely possibility of death”) spelled out to them. Any possible complication with an incidence greater than 1 : 100 or 1 : 200 should certainly be explained, so that a frank discussion of the “pluses and minuses” of anticipated therapeutic procedures, such as removal of large sessile polyps or dilation of strictures, should be mandatory. Ideally, the endoscopist should quote personal figures and experience.

It is logical and our routine practice to mention to all adult patients the remote possibility of postpolypectomy delayed bleeding occurring for up to 14 days post-procedure, in case a polyp is found incidentally during colonoscopy and is judged to require removal (even though the procedure is scheduled as “diagnostic”). Most patients will acquiesce immediately, but a commonsense discussion of practicalities is relevant. A patient about to have a holiday in remote parts or organizing a family wedding or other major event may be disinclined to take any risk whatever—and would justifiably be aggrieved should a complication occur.

Contraindications and infective hazards

There are few patients in whom colonoscopy is contraindicated. Any patient who might otherwise be considered for diagnostic laparotomy because of colonic disease is fit for colonoscopy, and colonoscopy is often undertaken in very poor risk cases in the hope of avoiding surgery.

- There is no contraindication to colonoscopy during pregnancy, although it might be best avoided in those with a history of miscarriage.

- There is no contraindication to the examination of infected patients (e.g. patients with infectious diarrhea or hepatitis) because all normal organisms and viruses should be inactivated by routine cleaning and disinfection procedures. Mycobacterial spores require a longer disinfection, so, after the examination of suspected tuberculosis patients and before/after the examination of AIDS patients (possible carriers of mycobacteria) prolonged disinfection is recommended (see Chapter 2).

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is unnecessary, according to current UK and US guidelines, even after heart valve replacement or previous bacterial endocarditis. It may be indicated in severely immunocompromised patients (see Chapter 2).

- Colonoscopy is absolutely contraindicated during, and for 2–3 weeks after, acute diverticulitis, due to the risk of perforation from the localized abscess or cavity. It should not be performed, or only with the greatest care and minimal insufflation, in any patient with marked abdominal tenderness, peritonism, or peritonitis.

- Colonoscopy is relatively contraindicated for 3 months after myocardial infarction, when it is unwise owing to the risk of dysrhythmias.

- Colonoscopy is relatively contraindicated in patients with known ascites or on peritoneal dialysis because of the probability of scope pressure causing transient release of bowel organisms into the bloodstream and peritoneal cavity.

- Colonoscopy should only be undertaken with good reason and extreme care when there is acute or severe inflammation (ulcerative, Crohn’s or ischemic colitis), especially if abdominal tenderness suggests an increased risk of perforation. If large and deep ulcers are seen it may be wise to limit or abandon the examination. After irradiation, especially a year or more after exposure, narrowed or obstructed bowel can be perforated without using excessive force. If insertion proves difficult it may be best to withdraw or to change to a smaller instrument.

- Other factors can be relevant and should be considered during the process of obtaining information and consent, including previous medical history and current medications. For obvious reasons, medications such as anticoagulants or insulin may affect management. A cardiac pacemaker theoretically contraindicates use of magnetic imaging or argon plasma coagulation (APC) but these should not affect modern insulated pacemakers. Patients with implantable defibrillators, however, are at risk from inappropriate firing of their devices during standard diathermy. These patients require full cardiac monitoring during electrosurgery, with a technician available to switch their device before and after the procedure.

Patient preparation

Most patients can manage bowel preparation at home, arrive for colonoscopy, and walk out shortly afterwards. Management routines depend on national, organizational, and individual factors. Overall management is influenced, among other things, by:

- cost

- facilities available

- type of bowel preparation and sedation used

- age and state of the individual patient

- potential for major therapeutic procedures

- availability of adequate facilities and nursing staff for day-care and recovery.

Experienced colonoscopists in private practice or large units are motivated to organize streamlined day-case routines, even for patients with large polyps. Some nationalities (Dutch, Japanese) do not expect sedation, whereas others (British, American) frequently insist on it. In countries with sufficient anesthesiologists (France, Australia) use of propofol or full general anesthesia has, regrettably in our opinion, become the norm for colonoscopy. These variables result in an extraordinary spectrum of performance around the world, from the many skilled colonoscopists who require patients for less than an hour on a “walk-in, walk-out” basis in an office or day-care unit, to others with less experience and a traditional hospital background who feel that many hours in hospital, or even an overnight stay, are essential.

Colonoscopy can be made quick and easy for the majority of patients. This requires both a reasonably planned day-care facility and an endoscopist with the confidence and skill to work gently and reasonably fast. Some flexibility of approach is wise. A very few patients are better admitted before or after the procedure. The very old, sick, or very constipated may need professional supervision during bowel preparation. Frail patients may merit overnight observation afterwards if their domestic circumstances are not supportive or they live far away. We do rarely admit a few patients for polypectomy, especially if the lesion is very large and sessile and the patient has a bleeding diathesis or is unavoidably on anticoagulants or antiplatelet medications (clopidogrel, etc.). Even such patients, however, providing they live near good medical support services and have been fully informed about what to do in a crisis, can often be justifiably managed on an outpatient basis, as complications are rare and can in any case be “delayed” several days post-procedure.

Bowel preparation

An informed team member should be available to talk to the patient at the time of booking to explain the procedure, including the importance of successful bowel preparation—although printed instructions and explanations will be sufficient for most patients. The majority of patients find that the worst part of colonoscopy is the bowel preparation and that the anticipation of the procedure (including fear of indignity, a painful experience, or the possible findings) is much worse than the reality of the colonoscopy itself. Anything that will justifiably cheer them up beforehand is extremely worthwhile, providing that there is understanding and compliance with dietary modification and bowel preparation. Minutes spent in explanation and motivation may prevent a prolonged, unpleasant, and inaccurate examination due to bad preparation. The patient needs to know that a properly prepared colon looks as clean and easy to examine as the mouth—whereas poor preparation can lead to a degradingly unpleasant, less accurate, and slower examination.

Written dietary instructions are well worthwhile, as many patients, anxious to get a good result, find it easier to follow specific instructions “to the letter.” Clear instructions avoid unnecessary anxieties and many telephone calls.

Limited preparation

Enemas alone are usually effective for limited colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy in the “normal” colon. The patient need not diet and typically has one or two disposable phosphate enemas (e.g. Fleet Phospho-soda®, Fletchers’, Microlax), self-administered or given by nursing staff. Examination can be performed shortly after evacuation occurs—usually within 10–15 minutes—so that there is no time for more proximal bowel contents to descend. The colon can often be perfectly prepared to the transverse colon in younger subjects (NB in babies phosphate enemas are contraindicated because of the risk of hyperphosphatemia). Note that patients with any tendency to faint or with functional bowel symptoms (pain, flatulence, etc.) are more likely to have severe vaso-vagal problems after stimulant enemas; make sure they are supervised or have a call button. Lavatory doors should be able to be opened from and toward the outside in case the patient should faint against the door.

Diverticular disease or stricturing requires full bowel preparation even for a limited examination, because bowel preparation will be less effective and enemas less likely to work.

If obstruction is a possibility, per oral preparation is dangerous, even potentially fatal. In ileus or “pseudo-obstruction” normal preparation simply does not work. One or more large-volume enemas are administered in such circumstances (up to 1 L or more can be held by most colons). A contact laxative such as oxyphenisatin (300 mg) or a dose of bisacodyl can be added to the enema to improve evacuation (see below).

Full preparation

The object of full preparation is to cleanse the whole colon, especially the proximal parts, which are characteristically coated with surface residue after limited regimens. However, patients and colons vary. No single preparation regime predictably suits every patient, and it is often necessary to be prepared to adapt to individual needs. Constipated patients need extra preparation; those with severe colitis may be unfit to have anything other than a warm saline or tap water enema. A preparation that has previously proved unpalatable, made the patient vomit, or that failed is unlikely to be a success on another occasion—a different one should be substituted. Recommendations are now published by respective societies on suitability for bowel preparation. Current data support “split-dose” administration (see below) to increase acceptability and resultant success of preparation.

Dietary restriction is a crucial part of preparation. The patient should have no indigestible or high-residue food for 24–48 hours before colonoscopy (avoiding muesli, fibrous vegetables, mushrooms, fruit, nuts, raisins, etc.). Staying on clear fluids for 24 hours is even better if the patient is compliant, but is not really necessary. Soft foods that are easily digested (soups, omelettes, potato, cheese, and ice-cream) can be eaten up to (and including) lunch on the day preceding colonoscopy. Only supper and breakfast before colonoscopy need to be replaced with fluids. Tea or coffee (with some milk if wanted) can be drunk up to the last minute, since minor fluid residues present no problem to the endoscopist.

Drink extra clear fluids—the more the better! Fruit juices or beer are found by many to be easier to drink in large quantities than water, and white wine or spirits can also help morale during the fasting phase. However, red wine is discouraged because it contains iron and tannates and, when digested with other dietary tannates, causes the bowel contents to become black, sticky, and offensive. Any other clear drink, water ices or sorbets (not blackcurrant), consommé (hot or cold), boiled sweets, or peppermints can all be taken up to the last minute. There is no reason why anyone should feel ravenous or unduly deprived of calories by the time of colonoscopy.

Medications or supplements containing iron should be stopped at least 3–4 days before colonoscopy, as organic iron tannates produce an inky black and viscous stool, which interferes with inspection and is difficult to clear. Constipating agents should also be stopped 1–2 days before.

Most medications can be continued as usual, except for modification of anticoagulant regimens and withdrawal of clopidogrel and similar platelet-inhibiting agents for one week before planned polypectomy.

PEG-electrolyte preparation

Balanced electrolyte solution with polyethylene glycol solution (PEG) is very widely used. This is primarily because it has formal approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (e.g. GoLYTELY®, NuLYTELY®, CoLyte®, KleenPrep®, etc.) and comes with suitable flavorings, convenient packaging, and is easily prescribed, but it is surprisingly expensive. Although the PEG component of a PEG–electrolyte mixture contributes the majority of the packaged weight, volume, and expense, it results in only a minority of the osmolality (sodium salts being, of physiological necessity, the important component). Even chilled, its taste is mildly unpleasant due to the Na2SO4, bicarbonate, and KCl included to minimize body fluxes. Modification of the original formula by omitting Na2SO4 and reducing KCl only slightly improves the taste. A further recent variant, apparently popular and effective, is MoviPrep®, which combines PEG–electrolyte with ascorbic acid (aspartame, the sweetening agent used in it, can be nauseating to some patients).

Patient acceptance of PEG–electrolyte oral preparation can be enhanced, without impairing results from the endoscopist’s point of view, by the simple expedient of administering the volume necessary in two half doses (“split administration”), with most drunk the evening before but the rest on the morning of the examination (see “Routine” below). There are conflicting reports about whether the addition of prokinetic agents or aperients improves results; the consensus is that it does not.

Mannitol

Mannitol (and similarly sorbitol or lactulose) is a disaccharide sugar for which the body has no absorptive enzymes. It is available ready-made as intravenous (IV) solutions that can be drunk. Mannitol solution is an isosmotic fluid at 5% (2–3 L) or acts as a hypertonic purge at 10% (1 L) with a corresponding loss of electrolyte and body fluid during the resulting diarrhea, although this is only of concern in the elderly and normally can be rapidly reversed by drinking. The solution’s sweetness can be nauseous to those without a sweet tooth, although this is much reduced by chilling and adding lemon juice or other flavorings. Children, in particular, tend to vomit it back. Mannitol solution alone (1 L of 10% mannitol drunk iced over 30 minutes, followed by 1 L of tap water) is a useful way of achieving rapid bowel preparation (in 2–3 hours) for those requiring urgent colonoscopy.

There is a potential explosion hazard after mannitol, because colonic bacteria possess the necessary enzymes to metabolize carbohydrates to form explosive concentrations of hydrogen. Electrosurgery should therefore be covered by CO2 insufflation or all colonic gas conscientiously exchanged several times by aspiration and re-insufflation.

Magnesium salts

Magnesium citrate and other magnesium salts are very poorly absorbed, acting as an “osmotic purge.” The gently cathartic properties of “spa” waters rich in magnesium salts, such as Vichy water, have been known since Roman times. Picolax®, a proprietary combination, produces both magnesium citrate (from magnesium oxide and citric acid) and bisacodyl (from bacterial action on sodium picosulfate). It tastes acceptable and works well in most patients. Taking 2–3 bisacodyl tablets in addition improves results, but can cause cramping.

For seriously constipated patients, magnesium sulfate, although unpleasant-tasting, is highly effective if taken in repeated doses (5 mL of crystals in 200 mL hot water every hour, followed by juice and other fluids). It can be guaranteed eventually “to move mountains.”

Sodium phosphate

Sodium phosphate, presented as a flavored half-strength equivalent of the phosphate enema (Fleet’s Phospho-Soda®) but administered orally, has received numerous good reports when trialed against 4 L PEG–electrolyte preparation. It is said to be as effective as PEG–electrolyte solution but is significantly more acceptable to patients, principally because the volume ingested is only 90 mL. Although the taste is generally disliked, this has been partially solved by the introduction of Phospho-Soda tablets. Sodium phosphate must be followed by at least 1 L of other clear fluids of choice—water, juices, lager, etc. Because concerns remain about the risk of significant electrolyte disturbances (hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia), which could initiate cardiac arrythmias, sodium phosphate is unsuitable for those with any degree of renal impairment, which includes most elderly patients.

Routine for taking oral prep

Low-residue diet instructions should have been followed, ideally for several days in the case of those with known constipation or slow transit. The patient should be supplied with petroleum jelly or barrier cream to avoid perianal soreness (colorless to avoid endoscope lens contamination as the scope is inserted through the anus). The evening before colonoscopy will be fluid-dominated—input and output—so social events should not be scheduled but there will be plenty of time for watching television or reading between “calls.”

As mentioned above, large-volume solutions are ideally split-administered in two doses, starting on the afternoon or evening before, but it is essential that some oral prep is taken on the morning of the examination so that cecal contents remain fluid and easily aspirated. If an afternoon examination is scheduled and the patient does not have a long distance to travel, both doses can be drunk on the day of examination.

The patient should be encouraged to carry on with normal activities, rather than sitting still during the drinking period; exercise stimulates transit and evacuation. Bowel actions should start within 1–3·hours, but can be much delayed in constipated patients or those who prove to have a long colon.

Bowel preparation in special circumstances

Children

Children usually accept pleasant-tasting oral preparations such as senna syrup or magnesium citrate very well. Drinking large volumes is less well accepted, and mannitol may cause nausea or vomiting. The childhood colon normally evacuates easily except, paradoxically, for colitis patients, who prove perversely difficult to prepare properly. Small babies may be almost completely prepared with oral fluids plus a saline enema. Phosphate enemas are contraindicated in babies because of the possibility of hyperphosphatemia.

Colitis patients

Colitis patients require special care, during and after preparation. Relapses of inflammatory bowel disease occasionally occur after overvigorous bowel preparation but balanced PEG–electrolyte solutions are well tolerated. A simple tap water or saline enema will clear the distal colon sufficiently for limited colonoscopy. Patients with severe colitis are unlikely to need colonoscopy at all, as plain abdominal x-ray, ultrasonography, or scanning will usually give enough information.

For severely ill patients any distension is risky and colonoscopy is positively contraindicated due to the potential for perforation. When the indication for colonoscopy in a colitis patient is to exclude cancer or to reach the terminal ileum to help in differential diagnosis, full and vigorous preparation is necessary.

Constipated patients

Patients with constipation often need extra bowel preparation. This is very difficult to achieve in patients with true megacolon or Hirschsprung’s disease, in whom colonoscopy should be avoided if at all possible. Constipated patients should have 48 hours on low-residue diet, as they normally take a high-fiber regime but have slow transit. They should continue any habitually taken purgatives in addition to the regime for colonoscopy preparation.

Colostomy patients

Colostomy patients are as difficult to prepare as normal subjects. Oral preparation is well tolerated, whereas enemas/colostomy washouts are tedious and difficult for nursing staff to perform satisfactorily, unless the patient is accustomed to this and can do it for themselves.

Stomas, pouches, and ileo-rectal anastomoses present few problems. Ileostomies are self-emptying and normally need no preparation other than perhaps a few hours of fasting and clear fluid intake. Ileo-anal pelvic pouches can be managed either by saline enema or by reduced volume of oral lavage. After ileo-rectal anastomosis, the small intestine can adapt and enlarge to an amazing degree within some months of surgery, so that if the object of the examination is to examine the small intestine, full oral preparation should be given. For a limited look, any conventional enema is usually enough (NB stimulant enemas sometimes cause vaso-vagal response).

Defunctioned bowel, for instance the distal loop of a “double-barreled” colostomy, always contains a considerable amount of viscid mucus and inspissated cell debris, which will block the colonoscope. Conventional tap water or saline rectal enemas or tube lavage through the colostomy are needed to clear a defunctioned bowel. Hypertonic (phosphate) or stimulant enemas will be less effective.

Colonic bleeding

Active colonic bleeding helps preparation, as blood is a good purgative. Some patients requiring emergency colonoscopy may need no specific preparation at all, providing that examination is started during the phase of active bright red bleeding. Position change during insertion of the instrument will shift the blood and create an air interface through which the instrument can be passed. Changing to the right lateral position clears the proximal sigmoid and descending colon, which is otherwise a blood-filled sump. Actively bleeding patients requiring preparation for more accurate total colonoscopy can be managed by nasogastric tube lavage, which allows examination within an hour or two and ensures that blood is washed out distal to the bleeding point, rather than carried proximally with enemas. Blood can be refluxed to the terminal ileum from a left colon source, which makes localization difficult unless it is being constantly washed downward by a per-oral high-volume preparation. Massively bleeding patients can be examined per-operatively with on-table colon lavage combining a cecostomy tube with a large-bore rectal suction tube (and bucket), but more often should be managed angiographically with no preparation at all.

Medication

Attitudes to medication differ greatly from country to country. We favour adapting to the individual patient.

Sedation and analgesia

All aspects of the procedure, including the medication options, should be explained when the colonoscopy booking is arranged. The patient should receive preliminary verbal and written explanation about bowel preparation and what to expect of the procedure (whether from doctor, nurse, or secretary). At this point some patients may judge (in countries where judgment is permitted) that they want full medication, others that they will hope to work normally or to drive afterwards. On arrival for colonoscopy, a few minutes of further explanation will reassure and calm most patients and allow the endoscopist to judge whether the particular individual is likely to require sedation, and if so how much. Most people tolerate some discomfort without resentment if they understand the reason for it. Few people expect to be semi-anesthetized for a visit to the dentist, but on the other hand they understandably expect the intensity and duration of any discomfort to be within “acceptable limits.” Pain thresholds and individual attitudes to pain are not always easy to predict before colonoscopy, because tolerance of the (peculiarly unpleasant) quality of visceral pain varies so much. It is sensible to warn the patient that there will be a few seconds of “wind” or a transient sensation of “urgency.”

During a typical and correctly performed colonoscopy, minor pain is experienced by the patient for only 20–30 seconds. Using moderate or no sedation, and employing the skills, changes of position, and other “tricks of the trade” described below, pain only occurs during looping in the sigmoid colon and while passing the sigmoid–descending colon junction. During the rest of a normal procedure a patient with average pain threshold should experience little more than mild distension or the urge to pass flatus. It is worth pointing out to the patient that pain is useful to the endoscopist because it shows that a loop is forming, but is not dangerous and can usually be stopped in a few seconds (by straightening out the loop that is causing it).

The use of sedation has advantages and disadvantages. The unsedated or very lightly sedated patient can cooperate by changing position, needs no recovery period, and can travel home unaided immediately. The colonoscopist is also encouraged to develop dexterous and gentle insertion technique. On the other hand, some endoscopists who never employ sedation also admit to only 80–90% success in performing total colonoscopy, presumably because some examinations are intolerable. If light “conscious sedation” is used (typically equivalent in effect to 2–3 glasses of wine or beer), the patient is likely to find the examination tolerable or to have amnesia for it. The endoscopist is helped to be thorough by the knowledge that the patient is comfortable, and is also more likely to achieve total colonoscopy in a shorter time. Using heavy sedation, endoscopists can get away with ham-handed and forcibly looping technique—a bad investment in the long term, less likely to achieve complete examinations, more likely to result in complications, and more expensive in instrument repair bills.

It is often said that it is dangerous to sedate, because the safety factor of pain is removed. This is not strictly true, providing that the endoscopist’s threshold of awareness lowers as the patient’s pain threshold is raised—taking restlessness or changes of facial expression as a warning that tissues and attachments are being overstretched.

Most endoscopists use a balanced approach to sedation that will be affected by many factors, including personal experience and the individual patient’s attitude. A relaxed patient with a short colon having a limited examination rarely needs sedation, but an anxious patient with a tortuous colon, severe diverticular disease, or a bad previous experience, may need deep sedation. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome or pain as presenting features are likely to be hypersensitive to stretch and will benefit from opiates.

A very few patients have a morbid fear of colonoscopy, a low pain threshold, or a known “difficult” colon that justifies offering light general anesthesia. General anesthesia is only likely to be hazardous if it allows an inexperienced colonoscopist to use brutal technique while the patient cannot protest. However, even experienced endoscopists are more likely to “push the limits” and to become more mechanistic if patients are routinely anesthetized and “out of it.”

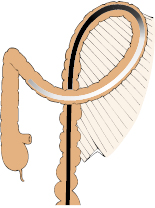

Nitrous oxide inhalation

Nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation can be a useful “half-way house” between no sedation and conventional IV sedation, for instance in a patient intending to drive after the procedure. The 50 : 50 nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture is self-administered by the patient, inhaling from a small cylinder fitted with a demand valve. Breathing the gas through a small single-use mouthpiece (Fig 6.1) avoids the difficulties that can be experienced in getting a good fit with a face mask, and also the phobia that some patients experience with masks.

The patient is shown how to inhale, then “pre-breathes” for a minute or two as the endoscopist prepares to start the procedure, with the intention of achieving gas saturation of the body fatty tissues. Thereafter it takes only 20–30 seconds of gas breathing, when required, to obtain a “high” that makes short-lived pain significantly more tolerable. Nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation should prove useful for some flexible sigmoidoscopies and, used alone, can be sufficient for motivated patients having total colonoscopy by a skilled endoscopist. Scared patients, prolonged or difficult examinations and examinations by inexpert endoscopists require conventional sedation.

Intravenous sedation

The ideal sedative regime for colonoscopy would last only 5–10 minutes, with a strong analgesic action but no respiratory depression or after-effects, allowing the patient to be comfortable yet accessible and able to change position during the procedure, but then to recover rapidly afterwards. The nearest approach to this ideal is currently given by IV delivery, through an in-dwelling plastic cannula, of a benzodiazepine hypnotic such as midazolam (Versed® 1.25–5 mg maximum) or diazepam (Valium® 2.5–10 mg maximum) either given alone or combined with a low dose of an opiate such as pethidine (meperidine 25–100 mg maximum) or fentanyl (50–100 mg). The benzodiazepine produces anxiolytic, sedational, and amnesic effects while the opiate contributes analgesia and (especially relevant to pethidine) a useful sense of euphoria.

In general, only a small dose of benzodiazepine should be given unless the patient is very anxious. The initial injection is given slowly over a period of at least 1 minute, “titrating” the dose to some extent by observing the patient’s conscious state and ability to talk coherently—some patients merely become loquacious. A small initial “starter dose” makes it possible to judge during initial insertion through the sigmoid whether the rest of the procedure is likely to be easy or difficult, and whether the patient is pain-sensitive or not. Half dosage in total is used for older, sicker patients but the amount required is unpredictable; younger patients may tolerate maximal doses and remain (fairly) coherent. If in doubt it is safer to underestimate the titration and give more later if necessary.

Use extra opiate rather than more benzodiazepine if extra medication is needed. Benzodiazepines make some patients even more restless and have no painkilling properties. Benzodiazepines and opiates potentiate each other, not only in effectiveness but also in side effects such as depression of respiration and blood pressure. Pulse oximetry should therefore be routinely used, and in most units nasal oxygen is administered in all sedated patients—with the caveat that this is contraindicated in severe chronic obstructive airways disease, where CO2 capnography would ideally be used.

- Benzodiazepines have a useful mild smooth-muscle antispasmodic action as well as their anxiolytic effect. Diazepam (Valium®) is poorly soluble in water and the injectable form is therefore carried in a glycol solution that can be painful and cause thrombophlebitis, especially if administered into small veins. For this reason, it is better to use water-soluble midazolam (Versed®). Midazolam causes a greater degree of amnesia, which can be useful to cover a traumatic experience but also “wipes” any explanation of the findings, which must be repeated later on. It should be borne in mind that IV midazolam dosage should be half that of diazepam.

- Opiates (pethidine notably) induce a useful sense of euphoria in addition to their analgesic efficacy. Pethidine may cause local pain when administered through small veins, particularly in children, but this can largely be avoided by diluting the injection 1 : 10 in water. A mild, symptomless small-vein phlebitis may be seen in a small minority of patients but invariably resolves spontaneously with no need for treatment. Pentazocine (Fortral®) is a weaker analgesic, more hallucinogenic and seems to have little to recommend it. Fentanyl (Sublimaze®) is very short-lived, so is strongly favoured by some endoscopists although it gives no sense of well-being, unlike pethidine.

- Propofol (Diprivan®), a short-lived IV emulsion anesthetic agent, is widely used for colonoscopy in some countries (USA, France, Germany, Australia) and increasingly in others. It should ideally be administered by an anesthetist because of the significant risk of marked respiratory depression but, with appropriate training and safeguards, has been extensively employed by endoscopists with an anesthetic-trained nurse assistant, with apparent safety and satisfactory results. Its short duration of action—giving full recovery within about 30 minutes—is an advantage over excessive doses of conventional sedatives. However, the patient can be rendered insensible and unable to cooperate with changes of position or to give early warning of excessive pain. We therefore prefer to reserve the use of propofol for selected patients having particular requirement for transient “heavy sedation”—usually because of previous difficulty or pain-sensitivity, or because of an anticipated problematic procedure.

Antagonists

The availability of antagonists to benzodiazepines (flumazenil) and opiates (naloxone) is invaluable, providing a safety measure for occasions when inadvertent oversedation has occurred. Some endoscopists routinely administer antagonists (intravenously and/or intramuscularly) to reduce the recovery period, which suggests mainly that their “routine” dosage regime is excessive. We use flumazenil extremely infrequently, but periodically administer naloxone intramuscularly on reaching the cecum if the patient appears oversedated. The patient is then conveniently awake by the time the examination is finished, without the risk of later “rebound” re-sedation, which is reported after IV naloxone wears off.

Antispasmodics

Antispasmodics induce colonic relaxation for at least 5–10 minutes and help to optimize the view during examination of a hypercontractile colon. Either hyoscine N-butylbromide (Buscopan®) 20 mg IV (in countries where it can be prescribed) or glucagon 0.5–1 mg IV are effective. Fears about anticholinergics initiating glaucoma are misplaced because patients previously diagnosed are completely protected by their eye drops, and those with undiagnosed chronic glaucoma are best served by precipitating an acute attack, which will cause the diagnosis to be made. Patients should be told to seek medical attention if they experience any eye pain. Glucagon is more expensive, but has no ocular or prostatic side effects.

Intravenous antispasmodics have a relatively short duration of action, leading some endoscopists to give them only when the colonoscope is fully inserted. Experienced endoscopists, sure of a rapid procedure, may give them at the start. There is an unproven suspicion that the bowel is rendered more redundant and atonic by antispasmodics and will be more difficult to examine; on the contrary, we find that the view is improved and have shown that colonoscope insertion is speeded up after using antispasmodics. Benzodiazepines have a weak antispasmodic effect, relaxing most colons except for those that are “irritable” or spastic. In the unsedated patient, therefore, antispasmodics may be particularly helpful and can also be a useful placebo for those who cannot have routine sedation because they need to drive home, but expect an “injection” to cover the procedure.

Insufflation with CO2 avoids post-procedure problems, especially in patients with irritable bowel disorder or diverticular disease. If air is used such patients can experience problems from air retention, with sudden onset of colic or discomfort after the procedure as the pharmacological effects of the antispasmodics and sedation wear off.

Equipment—present and future

This chapter aims to “make colonoscopy easy,” but this also depends to a fair degree on the instrumentation used. We have tried to generalize and be noncommercial in approach, as the colonoscopes of all manufacturers are serviceable and we have used many of them—although with individual preferences. A number of ingenious innovations are under current evaluation, designed to propel or guide the colonoscope or to view the colon more easily. While enthusiastic for future improvements and innovations, we have deliberately excluded these from the present account, which describes the best ways to manage the “push” colonoscopes currently used, including those with in-built stiffening or “magnetic imaging” facilities.

Colonoscopy room

Most units perform colonoscopies in undesignated endoscopy rooms, because the only special requisite for colonoscopy is good ventilation to overcome the evidence of occasional poor bowel preparation. In a few patients with particularly difficult and looping colons it has in the past been helpful to have access to x-ray facilities, especially in teaching institutions. Magnetic imaging (see below) performs the same function without using x-rays; it is increasingly used. We hope that it will spread worldwide to help teaching and the logical performance of colonoscopy.

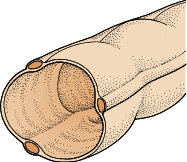

Colonoscopes

Colonoscopes are engineered similarly to upper gastrointestinal endoscopes, but are longer, have a wider diameter (for better twist or torque control), and have a more flexible shaft. The bending section of the colonoscope tip is longer and more gently curved, avoiding impaction in acute bends such as the splenic flexure. Ideal future colonoscopes ought to have electronic steering to make single-handed insertion easier; present angulation control mechanisms are almost unchanged from those of early gastrocameras and gastroscopes and are poorly suited to the more finicky steering movements during colonoscopy.

The introduction of variable stiffness instruments avoids the need to choose the “right colonoscope for the job” at the stage of purchase or before starting examination of a particular patient—especially one known or predicted to have a long “difficult” colon or severe adhesions. Long colonoscopes (165–180 cm) are able to reach the cecum even in redundant colons and so are our preferred routine choice of instrument (see also “variable-stiffness colonoscopes” below). Intermediate-length instruments (130–140 cm) are considered by some, including most German or Japanese endoscopists, to be a good compromise, almost always reaching the cecum. The only advantage of using 70-cm flexible sigmoidoscopes for limited examinations is that the endoscopist knows from the onset that the procedure will be limited, so avoiding the temptation to go further. However, as flexible sigmoidoscopy can be performed with a longer instrument (a pediatric colonoscope is ideal) there is no reason to purchase flexible sigmoidoscopes for an endoscopy unit, although they may have an essential role in the office of a primary-care physician or an outpatient facility.

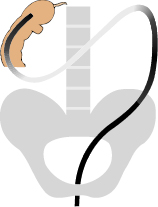

Variable-stiffness colonoscopes

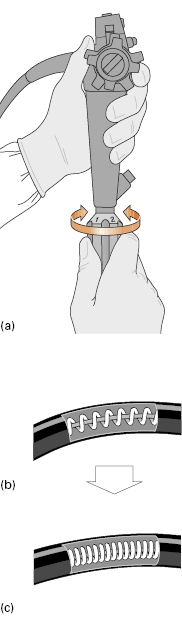

Variable-stiffness colonoscopes (Innoflex®, Olympus Corporation) have a twist control on the shaft (Fig 6.2a) that forcibly compresses and rigidifies an internal steel coil similar to that in a bicycle brake cable (Fig 6.2b,c Video 6.2 ). Compressing the coil stiffens it and the shaft/insertion tube within which it lies. The last 30 cm to the tip of the bending section is left “floppy” at all times. The bonus of using a variable-stiffness colonoscope is that, without having to withdraw and exchange instruments, the endoscopist can select a relatively “floppy” shaft mode to pass looping sections of the colon, then twist to apply “stiff” mode, so discouraging re-looping after the scope has been straightened out, typically at the splenic flexure.

). Compressing the coil stiffens it and the shaft/insertion tube within which it lies. The last 30 cm to the tip of the bending section is left “floppy” at all times. The bonus of using a variable-stiffness colonoscope is that, without having to withdraw and exchange instruments, the endoscopist can select a relatively “floppy” shaft mode to pass looping sections of the colon, then twist to apply “stiff” mode, so discouraging re-looping after the scope has been straightened out, typically at the splenic flexure.

Fig 6.2 (a) Variable-stiffness colonoscopes have a twist control on the shaft. A pull-wire within an internal spring-steel coil (b) compresses the coil and stiffens it (and the scope) (c).

Variable-stiffness scopes thus combine, in one colonoscope, many of the virtues of both standard and pediatric instruments. They prove significantly easier and less traumatic to use in most patients found previously to be “difficult” to examine—especially where the problem was due to uncontrollable looping and discomfort. As any first-time patient may prove to be difficult, a long, variable-stiffness instrument is our “colonoscope of choice.”

Pediatric colonoscopes

Pediatric colonoscopes of small diameter (9–10 mm) are available with either standard, “floppy,” or variable-shaft characteristics. They are invaluable for the examination of babies and children up to 2–3 years of age but also have a role to play in adult endoscopy and are the preferred choice of some skilled endoscopists. As well as allowing examination of strictures, anastomoses, or stomas that would be impassable with the full-sized colonoscope, they are often much easier to pass through areas of tethered postoperative adhesions or severe diverticular disease. The pediatric colonoscope bending section is more flexible, making it easier to obtain a retroverted view of some awkwardly placed polyps, whether in the distal or proximal colon, in order to ensure complete removal. Floppy pediatric instruments are also particularly comfortable and easy to insert to the splenic flexure, tending to conform to the colon in a spontaneous spiral configuration, which avoids difficulty in passing to the descending colon.

For limited adult examinations, as for strictures or diverticular disease, a pediatric gastroscope can also be used (it has the bonus of an even shorter bending section, but the disadvantage of limited downward angling capability). The stiff shaft of a gastroscope, however, makes it less suitable than the pediatric colonoscope for examinations of small children and babies.

Instrument checks and troubleshooting

The functionality of the colonoscope should be checked before examination, because imperfections can be difficult to spot or tedious to remedy during it. Colonoscopy can be difficult enough without adding problems in instrument performance.

Insufflation/lens washing checks are essential before every colonoscopy. Because air flow and water wash share a short common exit channel (see Fig 2.5) the quickest way of simultaneously checking air/water functionality is to depress the water-wash valve and look for a healthy squirt from the scope tip. Once the procedure has started it is difficult to assess inadequacy of air flow and insufflation pressure, the resulting poor view making it seem that the colonoscopy is “difficult” or the colon apparently “hypercontractile.” A great deal of wasted time can be avoided by noticing any such problem before starting, and correcting it or changing instruments.

If there is no insufflation at all, check the light source. Is the air pump switched on? Are the umbilical and water-bottle connections pushed in fully and the water bottle screwed on? Is the rubber O-ring in place on the water-bottle connection? Is the air/water valve in good condition and seated properly (or the CO2 valve in position where relevant), as it will otherwise allow air leakage? If in doubt, proper air insufflation pressure and flow can be proven by blowing up a rubber glove wound over the scope tip.

Water-wash failure is unusual, except because of an empty water bottle or a faulty air/water valve.

Suction failure can be caused by valve blockage, which should be obvious on careful inspection or changing the valve, or by debris blocking the suction channel. If this is in the shaft it can be dislodged by water-syringing through the biopsy port. Removing the suction valve and covering the opening on the control head with a finger is a quick way of improving suction pressure and can result in rapid clearance of the whole system (as when sucking polyp specimens). Applying the sucker tube directly to the suction-channel opening can also be effective in clearing particulate debris. As a final resort the whole suction system can be cleared by retrograde-syringing using a 50-mL bladder syringe and tubing attached to the suction port on the umbilical. Push the suction valve and also cover the biopsy port during this procedure to avoid unpleasant (refluxed) surprises.

Accessories

All the usual accessories are used down the colonoscope, including biopsy forceps, snares, retrieval forceps or baskets, injection needles, cytology brushes, washing catheters, dilating balloons, etc. Long and intermediate-length accessories work equally well down shorter instruments, so it is sensible to order all accessories to suit the longest instrument in routine use. Other manufacturers’ accessories also work down any particular instrument and, as some are better than others, it is worth taking advice from colleagues when buying replacements.

Carbon dioxide

Few colonoscopists, regrettably, use CO2 insufflation, although its use has much to commend it. CO2 was originally used instead of air because of the explosive potential of colonic gases during electrosurgery. However, with the exception of bowel preparation using mannitol, the prepared colon has been shown to have no residual explosive gas. Nonetheless, even for routine examinations, the use of CO2 offers the striking advantage that it is cleared from the colon 100 times faster than air (through the circulation, to the lungs and then breathed out). This means that 10–15 minutes after finishing an exam using CO2 insufflation, the colon and small intestine are free of any gas and the patient’s abdomen is deflated, whereas air distension can remain and cause abdominal bloating and discomfort for many hours, which is especially distressing for irritable bowel patients. In the unlikely event of perforation or gas leak (pneumoperitoneum), air under pressure would add to the hazard, whereas rapidly absorbed CO2 and a well-prepared colon should markedly reduce it.

Any patient with ileus, pseudo-obstruction, stricturing, severe colitis, diverticular disease, or functional bowel disorder should benefit from the added safety and comfort of using CO2 rather than air insufflation.

Low-pressure, controlled-flow CO2 delivery systems with fail-safe pressure-reducing features are available commercially. These remove any risk of the patient being exposed to the hazard of high pressure from the cylinder in the event of failure of the conventional flow-meter. A CO2 insufflation valve can be substituted for the usual air/water valve, but in practice it is easier to connect the CO2 supply to the water bottle (Fig 6.3) and use the normal air/water valve, as the modest leakage of CO2 into room atmosphere is of no more consequence than having another person in the room.

Magnetic imaging of endoscope loops

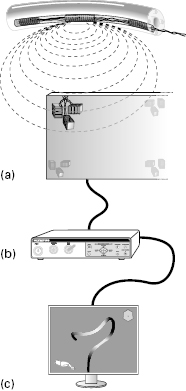

There is a need to know what shaft loops have formed during colonoscope insertion and where the tip is. In 1993 two UK groups introduced prototype magnetic imagers to “position-sense” the configuration of the instrument shaft, producing a moving 3D image on a computer monitor. Small coils within the instrument (or in a probe passed down its instrumentation channel) generate pulsed magnetic fields that energize larger sensor coils in a dish alongside the patient, computed to produce a real-time monitor graphic display (Fig 6.4). Two systems are commercially available: ScopeGuide® (Olympus Corporation) (Video 6.3 ), which uses coils incorporated within the shaft of the scope, and a catheter-based system inserted down the accessory channel of an ordinary colonoscope (Fujinon Magnetic Endoscopic Imaging). These produce fields no stronger than those of a television set and are safe for continuous use, except for patients with cardiac pacemakers.

), which uses coils incorporated within the shaft of the scope, and a catheter-based system inserted down the accessory channel of an ordinary colonoscope (Fujinon Magnetic Endoscopic Imaging). These produce fields no stronger than those of a television set and are safe for continuous use, except for patients with cardiac pacemakers.

Fig 6.4 (a) Small coils within the scope generate magnetic fields, (b) energizing larger coils in the receiver dish beside the patient; (c) the signals are then processed as a 3D image on the monitor.

In use, magnetic imaging makes many previously difficult and looping colons much quicker and easier to intubate, and also ensures that the endoscopist knows at all times where the colonoscope tip has reached and what loops have formed. It rationalizes many of the uncertainties of colonoscopy, and can be a boon to both beginners and experts. The magnetic imager is particularly helpful in patients with a long colon, who can be preselected on the basis of a history of constipation or the presence of hemorrhoids, or if they report a delayed response to bowel preparation.

Other techniques

Several other simple and straightforward amendments to standard insertion techniques are beginning to find favour. Water-immersion colonoscopy entails filling the colon with water to “smooth out” the floppy haustra and create a relatively straight colon. Cap-assisted colonoscopy uses a clear plastic cap attached to the tip of the colonoscope to assist with negotiating tight bends and can improve mucosal visualization on withdrawal. There are also many novel technologies in development to improve insertion and inspection (such as computer-controlled bending scopes, called retroscopes), but are not yet in routine use and are therefore currently beyond the remit of this book.

Anatomy

Embryological anatomy (and “difficult colonoscopy”)

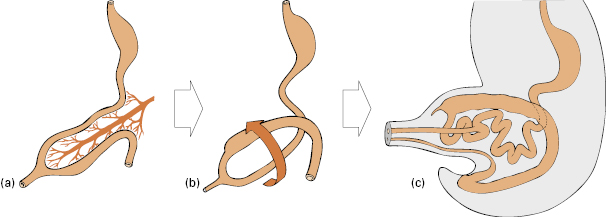

The embryology of colon development is complex and somewhat unpredictable, especially in terms of its outcome for mesenteries and fixations, which probably explains the extraordinarily variable configurations into which the colon can be pushed during colonoscopy (Video 6.4 ). The fetal intestine and colon initially develop as a functionless muscle tube joined at its midpoint to the yolk-stalk. This muscle tube lengthens into a U-shape on a longitudinal mesentery (Fig 6.5a). As the embryo at this 5-week stage is only 1 cm long, the lengthening intestine and colon (Fig 6.5b) are forced out into the umbilical hernia (Fig 6.5c). The gut loop thus differentiates into the small and large intestine outside the abdominal cavity. By the third month of development the embryo is 4 cm long and there is room within the peritoneal cavity for first the small, and then the large, intestine to be returned into the abdomen. This occurs in a fairly predictable manner, with the end result that the colon is rotated around so that the cecum lies in the right hypochondrium and the descending colon to the left of the abdomen (Fig 6.6a).

). The fetal intestine and colon initially develop as a functionless muscle tube joined at its midpoint to the yolk-stalk. This muscle tube lengthens into a U-shape on a longitudinal mesentery (Fig 6.5a). As the embryo at this 5-week stage is only 1 cm long, the lengthening intestine and colon (Fig 6.5b) are forced out into the umbilical hernia (Fig 6.5c). The gut loop thus differentiates into the small and large intestine outside the abdominal cavity. By the third month of development the embryo is 4 cm long and there is room within the peritoneal cavity for first the small, and then the large, intestine to be returned into the abdomen. This occurs in a fairly predictable manner, with the end result that the colon is rotated around so that the cecum lies in the right hypochondrium and the descending colon to the left of the abdomen (Fig 6.6a).

Fig 6.5 (a) The fetal intestine and colon start on a longitudinal mesentery (b) then rotate as the small intestine elongates (c) and from 5 weeks (1 cm embryo) to 10 weeks (4 cm embryo) are in the umbilical hernia.

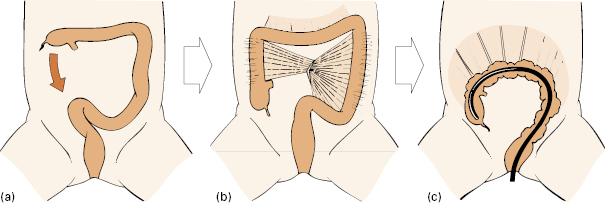

Fig 6.6 (a) The embryonic colon extends on its mesentery, (b) then partial fusion of the mesentery and peritoneum occurs at 3 months, (c) although sometimes the colon remains mobile.

With further elongation of the colon, the cecum normally migrates down to the right iliac fossa. At this stage, the mesentery of the transverse colon is free but the mesenteries of the descending and ascending colon, pushed against the peritoneum of the posterior abdominal wall by the fluid-filled and bulky small intestine, fuse with it so that the ascending and descending colon typically becomes retroperitoneal and fixed (although not always—see below) (Fig 6.6b).

Incomplete fusion of the mesocolon to the posterior wall of the abdomen results in a relatively free-floating colon. Such a mobile colon can be a nightmare for the colonoscopist, because there are no fixed points at which to obtain leverage, and few of the usual “tricks of the trade” will work, as most of them depend on withdrawal and leverage against fixations. The explanation for this variation from normal development may be the failure of enteric innervation of the intestinal muscle tube in early embryonic development. An atonic, bulky, and dysfunctional fetal intestine and colon will be retained longer than usual outside the abdomen in the umbilical hernia, until the developing abdominal cavity is large enough to re-accommodate it. Delayed return of a large colon into the abdomen will cause it to miss the “milestone moment” for retroperitoneal fixation and fusion to occur (usually by 10–12 weeks after conception). The long, mobile (and increasingly dysfunctional) colon may present clinically in childhood with straining at stool and bleeding, in teenage years with constipation, or in adulthood with hemorrhoids, variable bowel habit, and flatulence.

Endoscopically such a colon is noted to be unusually capacious, long, and often atypically looping, but it can also be dramatically squashed down and shortened when the colonoscope is withdrawn at the cecum (typically to a length of only 50–60 cm), proving the lack of fixations. Suggestive evidence that this is a genetically determined abnormality of development is the frequency of other first-degree relatives (especially on the female side and sometimes over several generations) known to have disturbance of habit, constipation, or flatulence. If endoscoped or imaged, the colon of such relatives (also their stomach and small intestine) are found to be similarly large, long, and mobile.

How often such failure of fusion, persistent colonic mesentery and mobility occurs is not clear from the literature. A persistent descending mesocolon has been found at postmortem in 36% with an ascending mesocolon in 10%. The persistence of a descending mesocolon explains most of the excessive loops and strange configurations that can be caused by the colonoscope passing the left colon and splenic flexure (Fig 6.7). Occasionally the cecum fails to descend and becomes fixed in the right hypochondrium (Fig 6.8); in others, where a free mesocolon persists, the cecum is mobile and can be pushed into weird configurations by the endoscope (Fig 6.9). Per-operative studies that we have undertaken show that colons in Asian patients are more predictably fixed than those in European patients.

Endoscopic anatomy

The anal canal, 3 cm long, extends up to the squamocolumnar junction or “dentate line.” Sensory innervation, and hence mucosal pain sensation, may in some subjects extend up to 5–7 cm into the distal rectum. Around the canal are the anal sphincters, normally in tonic contraction. The anus may be deformed, scarred, or made sensitive by present or previous local pathology, including hemorrhoids or other conditions. Normal subjects may also be sore from the effects of bowel preparation.

There are two potentially serious consequences from the fact that the hemorrhoidal veins drain into the systemic (not the portal) circulation:

The rectum, reaching 15 cm proximal to the anal verge, may have a capacious “ampulla” in its mid-part as well as three or more prominent partial or “semilunar” folds (valves of Houston) that create potential blind spots, in any of which (as well as the distal rectum) the endoscopist can miss significant pathology. Digital examination, direct inspection and, where appropriate, a rigid rectoscope/proctoscope are needed for complete examination of the area. “Video-proctoscopy” (anoscopy—see below) is a convenient way of visualizing the anal canal, rectal mucosal prolapse, or hemorrhoids, but not the remainder of the rectum (which requires inflation for careful inspection and, where possible, instrument retroversion). Prominent, somewhat tortuous, veins are a normal feature of the rectal mucosa and should not be confused with the rare, markedly serpiginous veins of a hemangioma or the distended, tortuous varices seen in some cases of portal hypertension.

The rectum is extraperitoneal for its distal 10–12 cm, making this part relatively safe for therapeutic maneuvers such as Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection removal (see below) of sessile polyps. Proximal to this it enters the abdominal cavity, invested in peritoneum. Whereas the colon surface is devoid of sensory nerves and pain-free, patients may experience “burning pain” for up to 5–7 cm above the anal verge. This is easily managed for polypectomy by intramucosal local anesthetic injection.

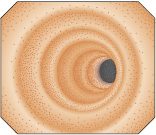

Mucosal “microanatomy” is visible to the discerning endoscopist. This includes the shiny surface coating of mucus, around 30% of the mucosal cells being mucus-secreting and described as “goblet cells” because of their flask-shaped mucus-containing inclusions. The “highlights” reflected off the surface by the protective mucus layer can show up fine underlying detail, such as the arc impressions of circular muscle fibers or the dappled, sieve-like reflections caused by the microscopic crypt or pit openings. Minor abnormalities, such as prominent lymphoid follicles and the smallest polyps or flat adenomas, often first catch the endoscopist’s eye through such reflections or “light reflexes” off the mucus layer. The mucosal columnar epithelium, around 50 cells thick, is transparent (unlike the horny squamous epithelium of the skin surface) and through it can be seen, often in exquisite detail, the paired venules and arterioles that make up the normal submucosal “vessel pattern.”

Colonic musculature develops into three external longitudinal muscle bundles, or teniae coli, and within these, the wrapping of circular muscle fibers. Both muscle layers are sometimes visible to the endoscopist (Fig 6.10). One or more of the teniae may be seen endoscopically as a longitudinal fold, because an unusually thin-walled, capacious colon can bulge out between its teniae. The circular musculature is seen as fine reflective corrugations under the mucosal surface, particularly in “spastic” or hypertonic colons. The distal colon, needing to cope with formed stools, has markedly thicker circular musculature than in the proximal colon, resulting in a tubular appearance (Fig 6.11) broken by the ridged indentations of the haustral folds. The thinner walled transverse colon is kept in triangular shape by the three teniae.

Haustral folds segment the interior of the colon. Those that are prominent in the proximal colon sometimes create “blind spots,” whereas they can be hypertrophied in sigmoid diverticular disease, also creating mechanical difficulties for the endoscopist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree